Neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of psychiatric diagnoses with onset early in development, functional impairments across the lifespan, and male predominance (

1). Children with neurodevelopmental disorders often do not outgrow their difficulties and are at increased risk of developing other psychiatric conditions, such as depressive disorders (henceforth, depression) (

2). For example, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have approximately double the risk for depression across development in comparison to typically developing peers (

3–

6). Importantly, depression in the context of ADHD may have an earlier onset (

7,

8), may recur more often (

9), and possibly may have worse severity (

10,

11). Given the impact of depression in the context of neurodevelopmental disorders, prevention is a priority (

2). To optimally inform research and interventions aimed at the prevention of depression in youths with neurodevelopmental disorders, the factors that are uniquely associated with depression in this population must be identified.

Neurodevelopmental disorders may be understood as extreme ends of continuous dimensions (

1), and thus, examining neurodevelopmental traits in samples from the general population may contribute to our understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders and the development of depression in their context. Previous population-based studies have corroborated associations between neurodevelopmental traits and the emergence of depression, but most of these studies have concentrated on specific traits in isolation, such as symptoms of ADHD (

12,

13) or of autism spectrum disorder (henceforth, autism) (

14,

15). Yet, evidence suggests that such traits are highly correlated with each other (

1) and with other co-occurring difficulties, including emotional dysregulation, relationship problems, and poor academic competence, which could explain the associations between neurodevelopmental traits and depression (

2). Hence, the exclusive focus on individual traits, without accounting for the simultaneous effects of other traits or highly correlated co-occurring difficulties and stressors, has limited capacity to clarify their unique associations over the course of development. Consequently, whether previous research findings represent specific associations between certain neurodevelopmental traits in childhood and depression later in life, or whether such findings are confounded by highly correlated factors, is unclear.

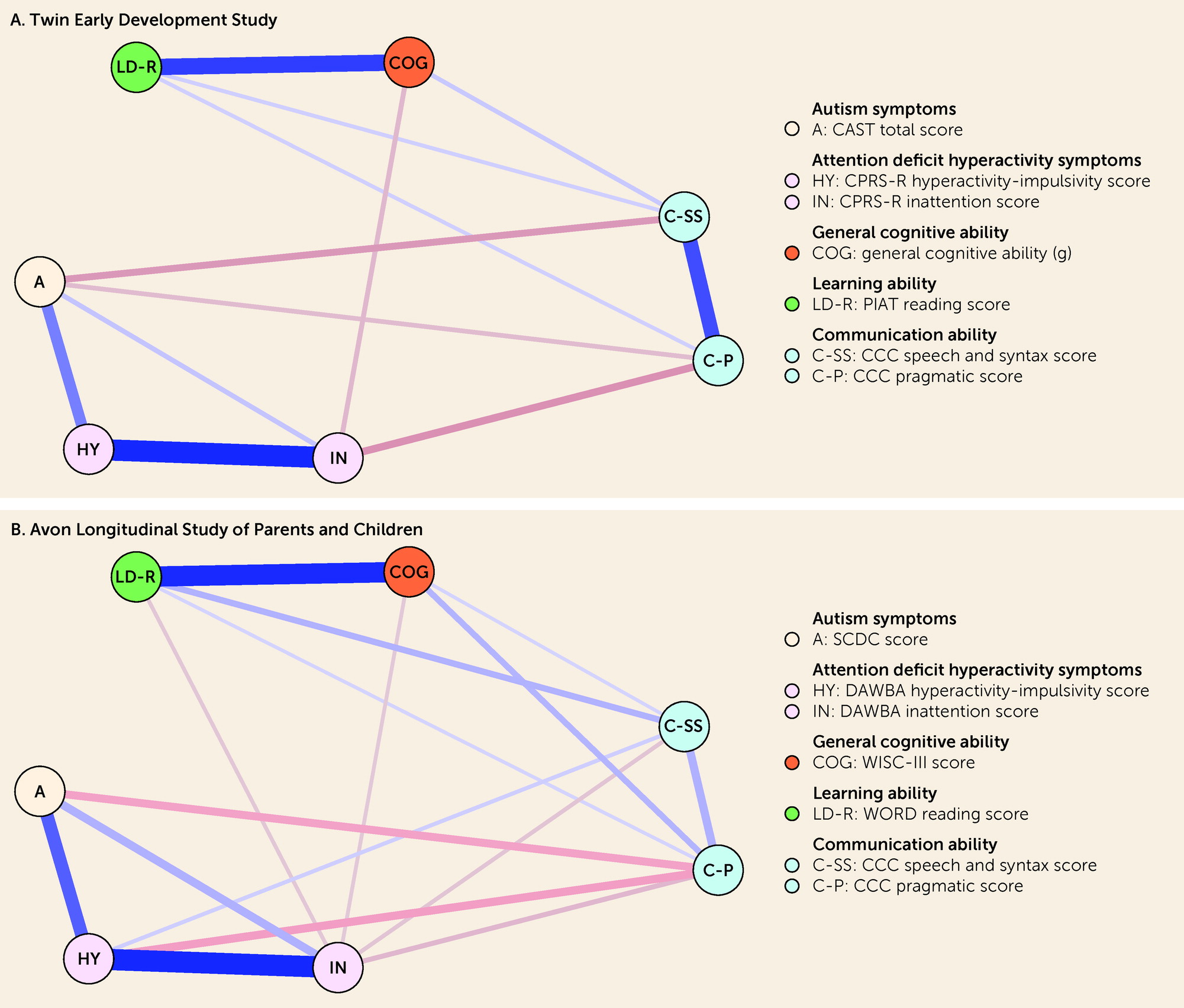

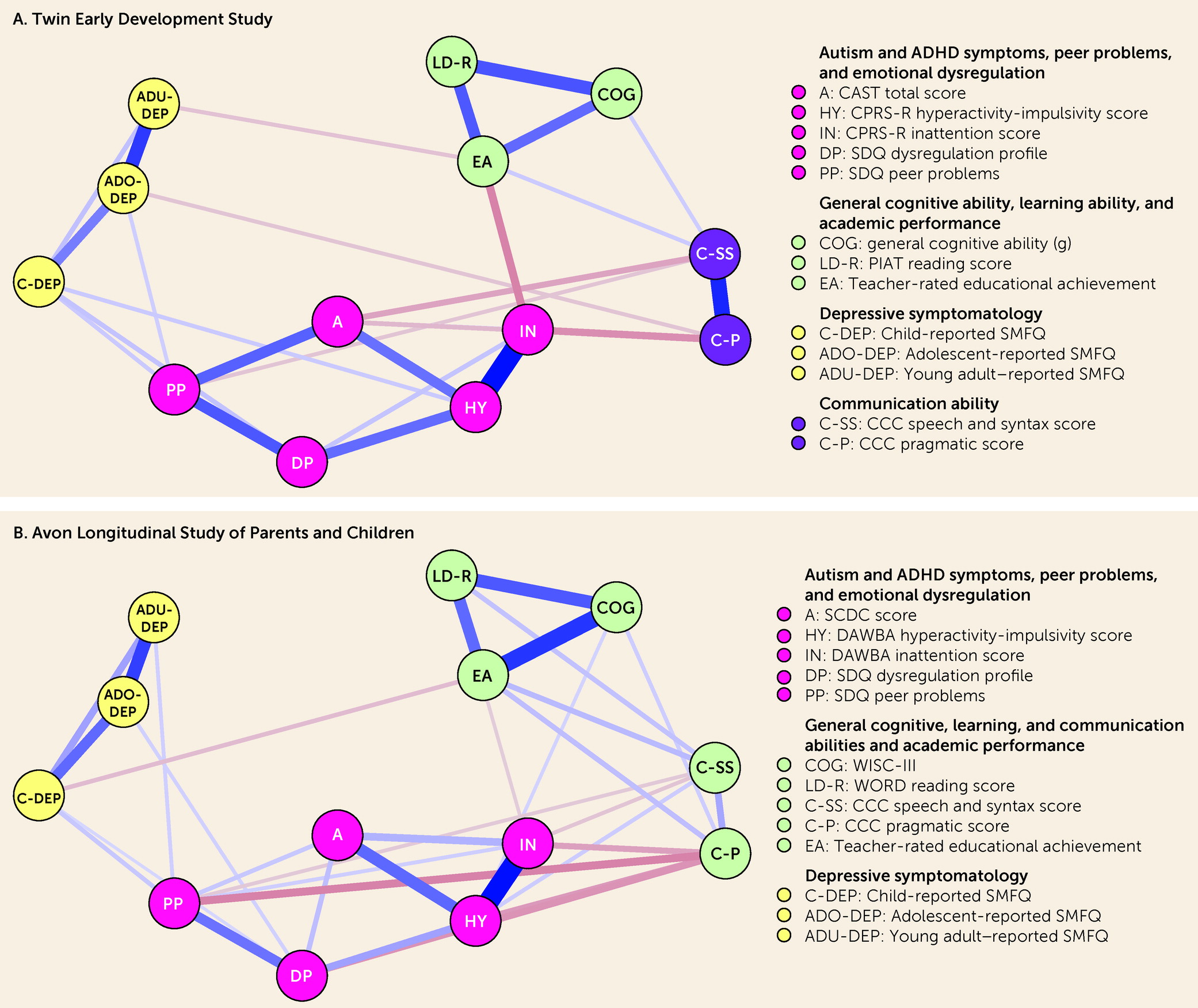

The present study aimed at filling this gap. We used data from two U.K. population-based cohorts and estimated Gaussian graphical models (GGMs) to identify unique associations between neurodevelopmental traits (autism and ADHD symptoms and general cognitive, learning, and communication abilities), socioenvironmental stressors (peer relationships and academic competence), and emotional dysregulation in childhood (ages 7–11 years) and depressive symptoms across development (ages 12, 16, and 21 years). GGMs are probabilistic network models that allow all variables to covary, resulting in partial correlations between any two given variables that represent conditionally dependent relationships after the effects of all other variables in the model have been controlled for (

16). There is a close relationship between partial correlations and coefficients from multiple regression models, and GGMs may be understood as linking separate multiple regression models, where each variable is regressed against the other variables in the network (

17). Hence, GGMs are powerful data-driven tools to map out multicollinearity and predictive mediation (

17) and may provide a clearer perspective on complex patterns of associations, such as those that exist between neurodevelopmental traits, socioenvironmental stressors, and emotional dysregulation in childhood and depressive symptoms across development.

Discussion

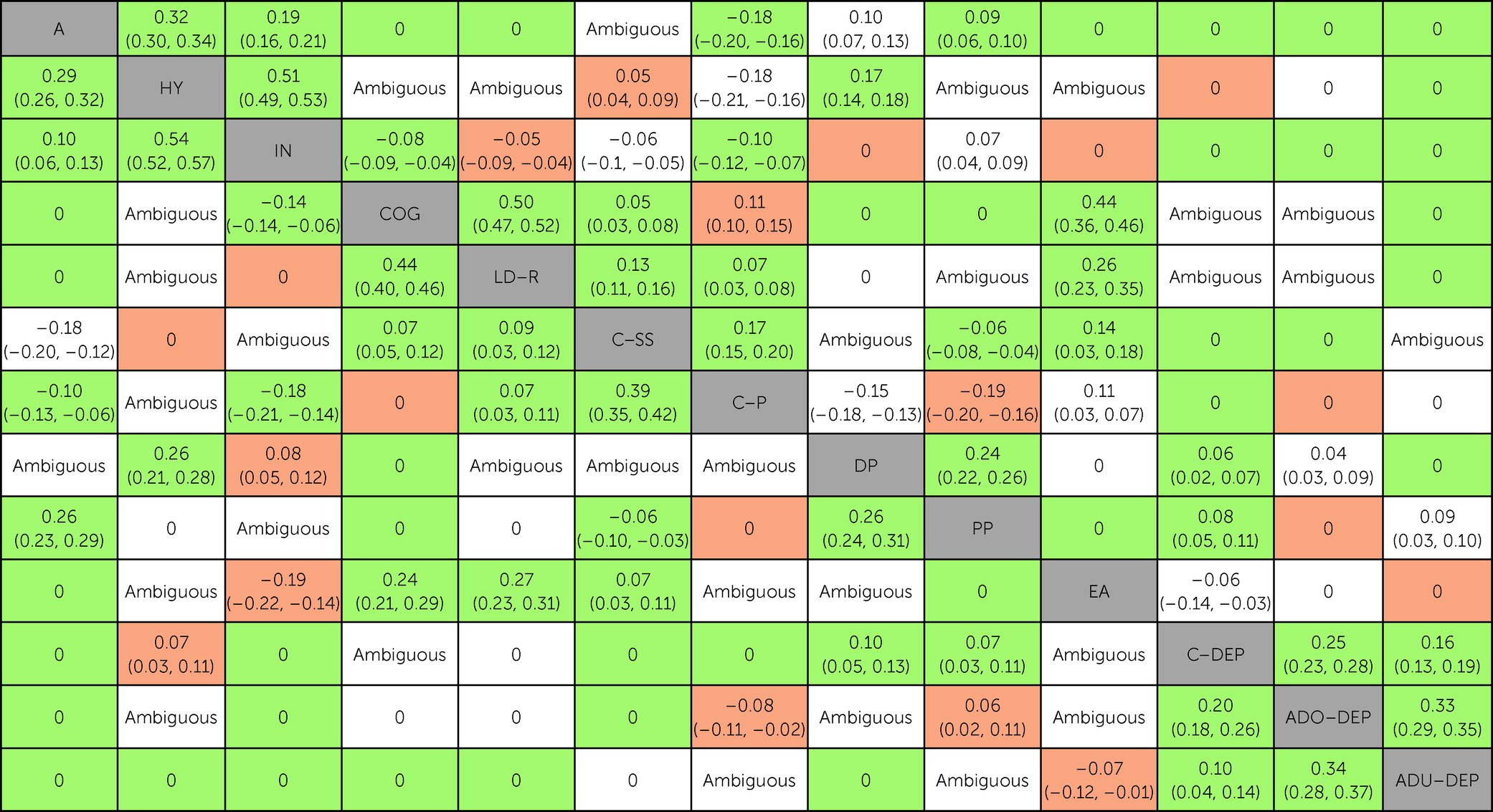

In this study, we evaluated the unique associations between neurodevelopmental traits, socioenvironmental stressors, and emotional dysregulation in childhood and depressive symptoms across development using data from two well-established U.K. longitudinal studies. By adopting a Bayesian approach, we were able to classify whether there was sufficient evidence in favor of a conditional association (i.e., non-zero partial correlation), conditional independence (i.e., partial correlation of zero), or insufficient evidence (i.e., “ambiguous”) for each pair of variables. Findings from the two cohorts supported the presence of numerous conditional associations between pairs of neurodevelopmental traits. There were several significant unadjusted associations (based on zero-order correlations) between neurodevelopmental traits and depressive symptoms across development; however, based on replicated data across cohorts, most of these pairs of variables with significant unadjusted associations were found conditionally independent, and none were conditionally associated, after accounting for socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation. In turn, socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation were conditionally associated with both neurodevelopmental traits and depressive symptoms, particularly during childhood. Based on replicated data across cohorts, neurodevelopmental traits in childhood could only be indirectly connected to depressive symptoms across development. Taken together, the present findings indicate that associations between neurodevelopmental traits in childhood and depressive symptoms across development could be explained by socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation.

We found numerous conditional associations between pairs of neurodevelopmental traits in childhood, which reinforces the importance of considering multiple neurodevelopmental traits simultaneously, rather than examining them individually, in future studies conducted with samples from the general population. Whether our findings will generalize to clinical samples is unclear, particularly for some of our unexpected findings (for example, autism symptoms were independent from general cognitive and learning abilities given the other traits). Because children with neurodevelopmental disorders often present with symptoms from multiple neurodevelopmental disorders simultaneously (

1), it is possible that similar associations would be found in a clinical sample, and future research should examine this question directly. It would be of particular interest to evaluate how neurodevelopmental traits are related to each other in a transdiagnostic sample of individuals diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders. Despite some consensus over the need to move beyond discrete diagnostic classification (

37), there has been relatively little clinical transdiagnostic research in the field.

We found several significant unadjusted associations between neurodevelopmental traits in childhood and depressive symptoms across development, which is in line with previous findings from population-based studies (

12–

15,

19). However, we expanded on this literature by demonstrating that, based on replicated findings across cohorts, most of these pairs of variables with significant unadjusted associations were found conditionally independent after accounting for the effects of socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation in multivariate analyses. Notably, based on replicated findings across cohorts, because neurodevelopmental traits in childhood could only be indirectly connected to depressive symptoms across development, any predictive effect from the former to the latter would be mediated by socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation in childhood. These findings suggest that intervening on socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation could contribute to the prevention of depression in children and young people with neurodevelopmental disorders. Overall, these indirect associations had small effects, but effective prevention efforts for depression will likely need to manage numerous risk factors with small effects (

38), including prevention efforts in the context of neurodevelopmental disorders. Consistent with this notion, in the context of ADHD, there is some preliminary evidence that programs focused on emotional dysregulation and family support may be efficacious in reducing depressive symptoms (

39). Additional research should continue to examine this important approach in ADHD and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Our findings provide strong evidence that associations between childhood neurodevelopmental traits and depressive symptoms across development could be explained by socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation, which is in line with theories about adult disorders with childhood antecedents (

40). However, we cannot definitively rule out the possibility of an association between neurodevelopmental traits in childhood and depressive symptoms across development because the absence of evidence does not equate to evidence of absence. Specifically, there were significant associations in unadjusted analyses but inconclusive evidence in GGMs for three pairs of variables involving neurodevelopmental traits and depressive symptoms for at least one time point. We found insufficient evidence (“ambiguous”) for associations between hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms and adolescent depressive symptoms in TEDS, and we found discordant findings across TEDS and ALSPAC for associations between hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms and childhood depressive symptoms and between pragmatic communication ability and adolescent depressive symptoms. GGMs require large samples to identify multiple small effects simultaneously, and even though our analyses included thousands of individuals, it is expected that some associations would be classified as “ambiguous” or fail to replicate (

41,

42). Additional studies are required to clarify these questions definitively.

The greatest strength of our study was the rigorous methodology that was adopted to increase confidence in our findings. Specifically, we formally tested the null hypothesis of conditional independence, we independently analyzed data from two cohorts, and we conservatively drew inferences for replicated associations only. Although the models were not identical, we were able to identify similar patterns of associations across the two cohorts that corroborated our hypotheses. GGMs are explorative in nature, and they are an ideal tool for hypothesis generation (

43). Our findings generated several hypotheses that should be tested—for example, using causal models such as directed acyclic graphs in clinical samples, which could contribute to advancing our understanding of the association between neurodevelopmental disorders and depression, as well as informing research aimed at the prevention of depression in youths with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Our study also has limitations. First, we were unable to include other important socioenvironmental stressors, such as home chaos and parent-child relationships. Variable selection in GGMs is driven by substantive considerations (

43), and some have argued that researchers should select the minimally complete set of variables to model the phenomena of interest considering the clinical hypothesis (

44). In GGMs, the associations between variables are dependent on the variables that are included in the model. We expect that including additional socioenvironmental stressors would strengthen the direction of the findings presented in this study since the inclusion of only a few variables explained most of the unadjusted associations between neurodevelopmental traits and depressive symptoms. Additional research could investigate this question directly if more measurements are available.

Second, there may be content overlap across some of the domains included in our analyses, which may have influenced our findings. Most notably, the measure of emotional dysregulation is partially composed of items belonging to the emotional and hyperactivity components of the SDQ scales, which may have some overlap with the measures for depressive and ADHD symptoms, respectively. However, empirical data have shown that the Child Behavior Checklist–dysregulation profile (CBCL-DP), a related measure of emotional dysregulation that is composed of three similar syndrome scales (anxious or depressed, attention problems, and aggressive behavior), is distinct from each of its components either alone or in tandem (

45). Additionally, the issue of content overlap has been discussed across other domains—for example, ADHD and autism symptoms (

46)—and may underscore a broader limitation of the current conceptualization of psychiatric phenomena; this issue might be applicable to other transdiagnostic studies.

Third, it is possible that the associations between depressive symptoms and neurodevelopmental traits would have been more robust if a strict phenotype of depression (e.g., major depressive disorder) had been considered rather than relying on depressive symptoms alone (

12). However, we opted to use dimensional scores rather than dichotomizing based on rating scale cutoffs because the latter approach has been shown to negatively impact the recovery performance of networks (

47).

Fourth, the neurodevelopmental trait data were collected at different time points spanning 2-year intervals from ages 8–10 (in TEDS) and ages 7–9 (in ALSPAC). Although this is not ideal because neurodevelopmental traits undergo maturational changes, children at these ages are at relatively similar developmental stages.

Lastly, both cohorts are susceptible to nonrandom attrition. For instance, in ALSPAC, it has been demonstrated that individuals at elevated risk of psychopathology are more likely to drop out of the study (

48). Detailed cohort-level attrition rates have been reported in previous publications (

49,

50). However, we used different statistical methods (multiple imputation and completer analyses) to assess the impact of missingness and found similar patterns of results.

In summary, our study adopted rigorous methodology and provided relevant findings for future research in the field of neurodevelopmental disorders and depression. Our findings indicate that associations between neurodevelopmental traits in childhood and depressive symptoms across development could be explained by socioenvironmental stressors and emotional dysregulation. These findings could both improve our understanding of the association between neurodevelopmental disorders and depression and inform research aimed at the prevention of depression in youths with neurodevelopmental disorders.