Major depressive disorder is a prevalent and disabling condition, and it is the leading cause of disability worldwide (

1–

3). Currently approved oral antidepressants work primarily via monoamine pathways (

4). Partial or inadequate response is common with these agents, and they typically take several weeks to produce clinically meaningful effects (

5). In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, about two-thirds of depression patients failed to achieve remission with first-line treatment, and of those who experienced a clinical response, approximately 60% did so only at or after 8 weeks of treatment (

6).

Involvement of the glutamatergic system in the pathogenesis of depression is suggested by data from neuroimaging, cellular, and clinical studies. Dextromethorphan is an uncompetitive antagonist of the

N-methyl-

d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (an ionotropic glutamate receptor) (

7) and a sigma-1 receptor agonist (

8). Blockade of the NMDA receptor and agonism of the sigma-1 receptor modulate glutamate signaling in the central nervous system (

9,

10). The clinical utility of dextromethorphan has been limited by its rapid and extensive metabolism through CYP2D6, yielding subtherapeutic plasma levels (

11). A tablet (AXS-05) combining dextromethorphan and bupropion (hereafter dextromethorphan-bupropion) has been formulated to increase the bioavailability and half-life of dextromethorphan and has been developed for the treatment of major depression. The bupropion component serves to increase dextromethorphan plasma concentrations by inhibiting its metabolism. A breakthrough therapy designation was granted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for dextromethorphan-bupropion for the treatment of major depressive disorder in March 2019. This designation is granted to candidate drugs that show potential for benefit above that of available therapies based on preliminary clinical data, and it provides the sponsor with added focus from and greater interactions with FDA staff during the development of the candidate drug (

12).

The high rate of failure to achieve signal detection in depression clinical trials has been well documented (

13–

15). A large analysis of depression clinical trials submitted for new drug applications over a 25-year period revealed a nearly 50% trial failure rate, and a declining treatment effect (drug-placebo difference), over this period (

13). Reasons identified in the literature for the poor signal detection and high failure rate of depression clinical trials include high and rising placebo response rates (

13,

16,

17), site rater biases resulting in baseline score inflation, inclusion of less severely symptomatic patients, and failure to exclude patients who were not eligible for study participation (

14,

18–

20). Approaches to addressing rising placebo rates have included placebo lead-in designs and the sequential parallel comparison design, which remove subjects with high placebo responses to increase the treatment effect (

21). These approaches have met with mixed success (

22). Approaches to reducing the inclusion of ineligible or inappropriate patients include use of a third party to reinterview potential patients to confirm disease severity and eligibility (

23). A limitation of these approaches is that the sites are not blinded to the use of the independent assessment. In this pilot trial, we utilized measures to potentially address the issues contributing to poor signal detection. These measures included confirmation of disease severity through independent assessment and comprehensive blinding of participating clinical trial sites.

Methods

Study Design

This was a 6-week randomized, double-blind, active-controlled phase 2 trial conducted at four sites in the United States from May 2018 to December 2018. The trial used bupropion, an approved antidepressant, as the control because it is a component of dextromethorphan-bupropion.

To address potential site rater biases contributing to inclusion of inappropriate patients, this study evaluated efficacy only in patients whose diagnosis and severity of major depressive disorder were confirmed, based on clinical review, by an independent assessor who was blinded to treatment assignment. The clinical review utilized only documentation collected by the sites at screening and baseline, including a complete medical history and clinician- and patient-reported outcome measures (described below, under Efficacy Assessments). The independent assessor did not have direct contact with study participants or access to any patient data collected after randomization. In order to reduce investigator expectation bias and therefore placebo response, sites were blinded to the primary efficacy variable and the presence of an independent assessor. Sites were provided a blinded protocol that presented the trial as a safety study with exploratory efficacy assessments. Detailed discussion of the efficacy analysis was limited to the statistical analysis plan, which was not provided to the sites.

All sites gained independent review board approval, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. The site investigators gathered the trial data, and the sponsor (Axsome Therapeutics) ensured that all persons administering rating scales were qualified and appropriately trained. The trial was conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonization’s guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (

24), the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (

25), and all regulatory requirements. The clinical trial was listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03595579).

Participants

The study evaluated patients 18–65 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of major depressive disorder and a current major depressive episode of moderate or greater severity. The diagnosis was established using the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder without psychotic features, based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, Clinical Trials Version (

26,

27), and the site investigator’s rating of a score ≥25 on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

28) and a score ≥4 on the Clinical Global Impressions severity scale (CGI-S) (

29). Confirmation of the diagnosis of major depressive disorder and a current major depressive episode of moderate or greater severity was performed by a blinded independent assessor based on a clinical review prior to database lock and study unblinding.

Key exclusion criteria included bipolar disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, treatment-resistant depression (defined as having had at least two failed adequate antidepressant treatments in the current major depressive episode), a substance use disorder within the past year, a lifetime history of psychotic disorder, a clinically significant risk of suicide, and a history of seizure disorder. Patients could have been on antidepressant treatment prior to study entry but were required to be completely off the prior treatment, with a washout of at least 1 week or five half-lives of the medication, whichever was longer, prior to the baseline visit and randomization. The screening period was up to 4 weeks to allow for any needed taper and washout of prior medications.

Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive oral treatment with either dextromethorphan-bupropion or sustained-release bupropion. In order to blind site investigators to the independent confirmation of diagnosis, all patients deemed eligible by the site investigators were randomized to receive study medication and were included in the safety population. As prespecified, patients whose diagnosis or severity was not confirmed by the independent assessor were excluded from the efficacy population.

Dextromethorphan-bupropion tablets and bupropion tablets were identical in appearance. The randomization schedule was computer generated using a permuted block algorithm that randomly allocated study drug to randomization numbers. All patients, investigators, and study personnel were blinded to treatment assignment, and no one involved in the performance of the study had access to the randomization schedule before official unblinding of treatment assignment.

Procedures

The double-blind treatment period was 6 weeks. Patients received their assigned study medication, dextromethorphan-bupropion (45 mg/105 mg tablet) or bupropion (105 mg tablet), once daily for the first 3 days and twice daily thereafter. The bupropion dosage in the control arm (210 mg daily) was selected to match the dosage incorporated in dextromethorphan-bupropion, enabling an appropriate comparison. Lower dosages (100 or 150 mg bupropion daily) have been shown to be efficacious in controlled trials (

30,

31). During the treatment period, patients tracked their mood daily by completing a daily visual analogue mood scale. Study visits occurred 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 weeks after the baseline visit. A safety follow-up visit occurred at week 7, 1 week after the last dose of study medication. There were no formal discontinuation criteria; patients were free to withdraw consent for any reason, and investigators were free to remove a patient from the study for any safety-related reason. The dosage of dextromethorphan-bupropion, titrated to twice daily, was selected based on the results of pharmacokinetic trials. Study drug adherence was monitored by counting the number of tablets dispensed and returned and by measurement of plasma concentrations of bupropion at end of study.

Efficacy Assessments

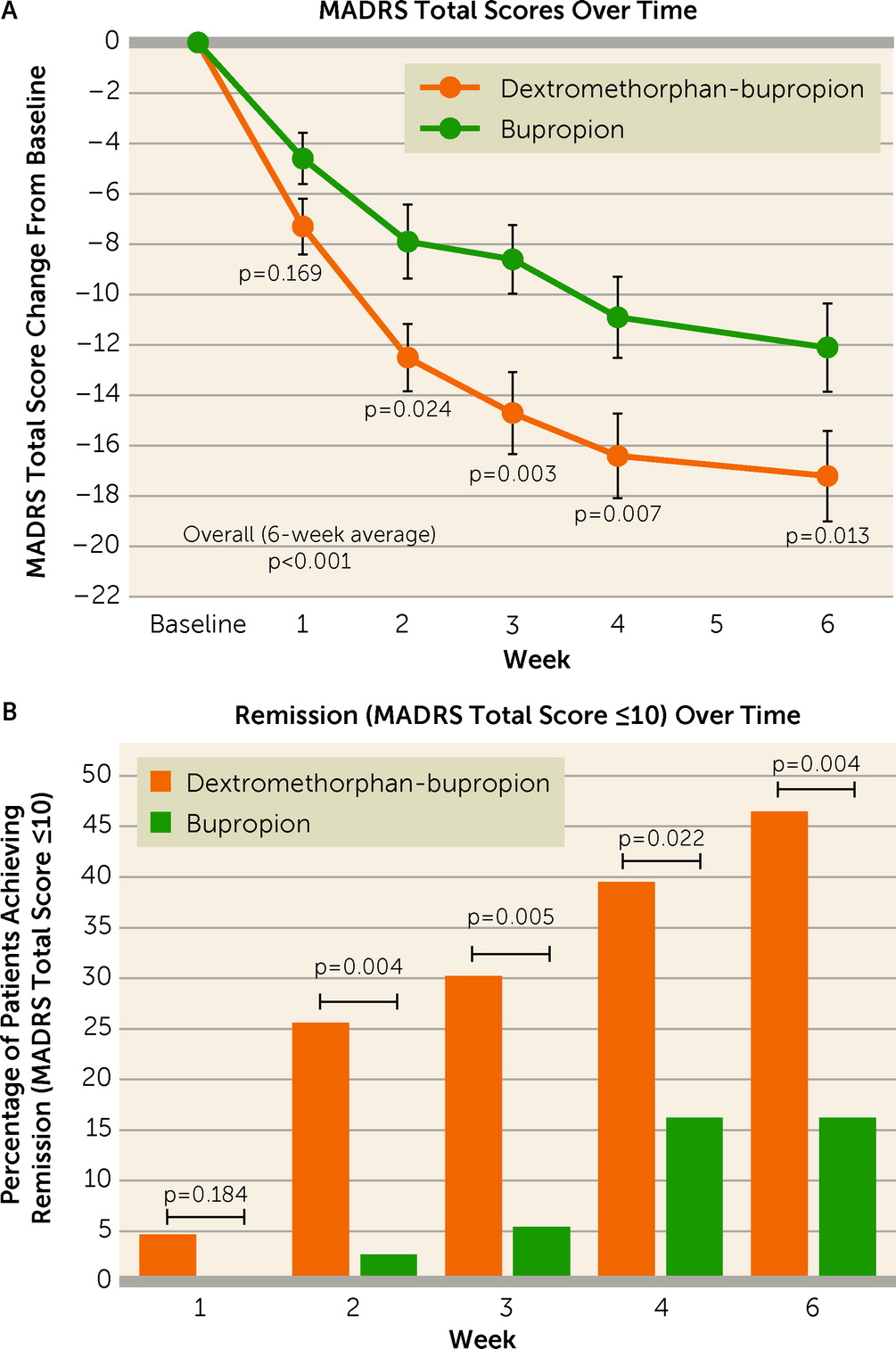

The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline to week 6 in the MADRS total score. The MADRS is a 10-item clinician-rated questionnaire ranging from 0 to 60, with higher scores representing more severe depression. The primary hypothesis testing was overall treatment effect on the MADRS score (average of change from baseline for weeks 1–6).

Secondary endpoints included clinical response (defined as a reduction ≥50% from baseline in MADRS total score); remission (defined as a MADRS total score ≤10); score on the Clinical Global Impressions improvement scale (CGI-I; scores range from 1 [very much improved] to 7 [very much worse]) (

29); score on the CGI-S (scores range from 1 [normal state] to 7 [among the most extremely ill]) (

29); score on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomology–Self-Rated (QIDS-SR; scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores representing more severe depression) (

32); and score on the MADRS-6 (a subscale of the 10-item MADRS evaluating the core symptoms of depression: apparent sadness, reported sadness, inner tension, lassitude, inability to feel, and pessimistic thought) (

33,

34).

Safety was assessed based on the incidence of adverse events; changes in vital signs, clinical laboratory measurements, physical examinations, and electrocardiograms; and assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior with the use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Adverse events during the treatment period were defined as adverse events occurring from the time of administration of the first dose of dextromethorphan-bupropion or bupropion until 7 days after the last dose.

Statistical Analysis

Two patient sets were prespecified for analysis. The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. The efficacy population (modified intent-to-treat population) consisted of all patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and a current major depressive episode of moderate or greater severity, confirmed by the independent assessor, who were randomized, received at least one dose of study medication, and had at least one postbaseline assessment.

The primary efficacy variable was the change from baseline in the MADRS total score, and the primary hypothesis testing was overall treatment effect. The overall treatment effect on the MADRS was assessed by averaging the change from baseline at each time point in the study (weeks 1–6). Changes from baseline in MADRS score were analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measures that included treatment (two levels: one indicating active treatment and two indicating the control treatment), week (five levels: weeks 1–4 and week 6), and treatment-by-week interaction as factors, baseline value as a covariate, and subject as a random effect. This method was used to analyze all other efficacy variables that assessed a change from baseline. Missing values were imputed via the last-observation-carried-forward method.

Overall treatment effects, treatment effects at individual postbaseline weeks, and the differences between treatment effects were estimated using least-squares mean estimation and are reported together with the two-sided 95% confidence interval of the treatment differences. Efficacy variables related to percentages (e.g., clinical response and remission rates) were analyzed via chi-square tests. The CGI-I was analyzed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9, and all hypothesis tests were conducted at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05.

If results were found to be positive on the primary hypothesis testing on the MADRS, then other analyses (response, remission) were to be performed on this variable to examine clinical relevance. As this was a phase 2 pilot study, secondary efficacy variables were not adjusted for multiplicity, and nominal p values for these are presented. The sample size assumed approximately 60 patients (30 per arm) with a confirmed diagnosis completing the double-blind period. The sample size of the study was determined based on prior reported experience with trials of a similar stage, in a similar patient population, with a similar objective.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, dextromethorphan-bupropion (AXS-05) demonstrated rapid, substantial, and statistically significant antidepressant efficacy compared with the active comparator bupropion on the primary efficacy variable (MADRS total score) and multiple other clinician- and patient-reported measures of depression severity. Given the known challenges in achieving signal detection in depression clinical trials, design features were implemented in this study to increase assay sensitivity and ensure evaluation of the appropriate patient population. To address potential site rater biases toward the inclusion of inappropriate patients, this study evaluated only patients whose diagnosis and severity of major depressive disorder were confirmed by a blinded independent assessor, based on clinical review. Another important design feature implemented to increase the ability to detect an efficacy signal in this phase 2 trial was the blinding of site investigators to the efficacy objective of the trial to reduce expectation bias.

Dextromethorphan-bupropion rapidly reduced depressive symptoms, as measured by the MADRS total score, as early as week 1, with statistically significant differences over bupropion observed by week 2 and at every time point thereafter. The treatment difference on the MADRS (dextromethorphan-bupropion change minus bupropion change) was substantial and consistent over time, being approximately 5 points at each time point from week 2 through week 6 (range, 4.5–5.6 points). This treatment effect over an active comparator compares favorably to the approximately 2.5-point mean difference from placebo seen at 6–8 weeks in antidepressant studies in the FDA database (

13,

35,

36).

Symptom remission is considered a desired goal in depression treatment because it is associated with better daily functioning and better long-term prognosis (

37). Rates of remission on the MADRS (a total score ≤10) were statistically significantly greater in the dextromethorphan-bupropion group starting at week 2 (p=0.004) and at every time point thereafter. Rates of remission on the patient-rated QIDS-SR (a total score ≤5) at week 6 similarly favored dextromethorphan-bupropion (p=0.020), demonstrating consistency between clinician- and patient-reported outcomes.

The MADRS core symptom subscale (MADRS-6) was evaluated because it has been suggested that core symptoms may be more sensitive to change from antidepressant treatment (

38). Results on the MADRS-6 were consistent with those on the 10-item MADRS, demonstrating greater improvements among patients in the dextromethorphan-bupropion group compared with those in the bupropion group, with statistical significance achieved on both measures starting at week 2 and at every time point thereafter.

Results of clinicians’ global assessments were consistent with the results from the symptom-specific scales and favored dextromethorphan-bupropion. Clinicians reported rapid and consistently greater reduction in disease severity, measured by the CGI-S, with dextromethorphan-bupropion compared with bupropion, which was statistically significant starting at week 2 (p=0.049) and at every time point thereafter, including week 6 (p=0.038).

Dextromethorphan-bupropion demonstrated a rapid onset of effect on depressive symptoms and global measures, with statistically significant improvements compared with bupropion observed starting at week 2 on several measures, despite the small sample size of the study. Dextromethorphan-bupropion demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in MADRS total score from baseline compared with bupropion starting at week 2 (p=0.024). Remission rates on the MADRS were statistically significantly superior in the dextromethorphan-bupropion group compared with the bupropion group starting at week 2 (26% compared with 3%; p=0.004). Global measures showed rapid improvement with dextromethorphan-bupropion, with statistically significant changes observed at week 1 on the CGI-I (p=0.045) and at week 2 on the CGI-S (p=0.049).

This study is the first controlled trial of dextromethorphan-bupropion in patients with depression. Murrough et al. (

39) reported results of the combination of dextromethorphan and quinidine in patients with treatment-resistant depression; however, that was an open-label trial with no control arm, which limits interpretation. The development of the combination of deuterated dextromethorphan and quinidine for the treatment of major depression was halted because results of a phase 2 placebo-controlled trial in this indication (NCT02153502) did not provide sufficient evidence of efficacy to justify continued development (

40). In the present phase 2 trial, the bupropion arm (210 mg/day) performed as expected, resulting in a substantial reduction (12 points) from baseline in MADRS total score at week 6. By comparison, in an 8-week, 362-patient, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, bupropion treatment at dosages of 150 mg/day or 300 mg/day resulted in a reduction of approximately 10 points from baseline in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score for each of the two dosages (

31) at week 8. This 10-point HAM-D change translates to an approximately 12-point change on the MADRS (

41), which is in line with the bupropion result in the present phase 2 trial. The bupropion dosage in the present trial was selected to match the dosage incorporated in dextromethorphan-bupropion, enabling an appropriate comparison. This dosage is lower than the usual target dosage of 300 mg/day as monotherapy stated in the FDA prescribing information for bupropion (

42).

Dextromethorphan-bupropion was safe and well tolerated in this trial. The incidences of adverse events were generally similar between the two groups except for dizziness, which was reported in 20.8% of the dextromethorphan-bupropion group, compared with 4.2% of the bupropion group. To estimate the true incidence of dizziness with dextromethorphan-bupropion, larger studies have been performed (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04019704). Rates of discontinuations due to adverse events were similar in the two treatment arms.

Unlike other NMDA receptor antagonists, dextromethorphan-bupropion was not associated with psychotomimetic effects. This tolerability profile could be related to the significantly faster rate of unblocking of the NMDA receptor channel reported for dextromethorphan as compared to other NMDA antagonists (

7). Dextromethorphan-bupropion was not associated with abuse-related adverse events in this trial. While dosing in this trial was only 6 weeks in duration, dextromethorphan-bupropion has been dosed for up to 1 year in a long-term open-label safety trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04039022). In that and other, larger controlled trials, dextromethorphan-bupropion to date has not been associated with abuse. Dextromethorphan-bupropion was not associated with weight gain or increased sexual dysfunction in this 6-week trial.

Limitations of this trial include exclusion of patients with inadequate symptom severity, psychotic or other psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, clinically significant risk of suicide, or significant medical comorbidities. These exclusions, along with prohibition of certain concomitant medications, may limit the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, treatment at experienced trial sites by specialized clinicians under a trial protocol with frequent clinical assessments may not reflect general practice. While most of the secondary outcomes favored dextromethorphan-bupropion over bupropion, the confidence intervals for the between-group differences were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. A greater number of patients in the bupropion arm were excluded by the independent assessment compared with the dextromethorphan-bupropion arm, which may affect the overall results. The imputation of missing values via the last-observation-carried-forward method may affect the results of categorical variables such as response and remission. Finally, the trial duration was limited to 6 weeks. The effect of long-term treatment with dextromethorphan-bupropion has been evaluated in a separate study. In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial, treatment with dextromethorphan-bupropion resulted in clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvements in depressive symptoms compared with the active comparator bupropion, and was well tolerated. Reductions in depressive symptoms with dextromethorphan-bupropion were statistically significant at week 2 and at every time point thereafter compared with bupropion alone.