National electronic health record (EHR) patient databases provide additional sources of information on time trends, offering important advantages, including data based on clinical interviews, diagnoses that are likely to capture more severe cases that are especially in need of treatment and services, and very large sample sizes (

14), potentially enabling study of change over time for conditions that are too rare to study in some population subgroups, such as individuals in minority racial/ethnic groups age 65 and older. EHR studies have indicated an increase in the prevalence of ICD-9-CM (

15) cannabis use disorder among hospital inpatients between 2002 and 2011 (

16) and between 1998 and 2014 (

17), among inpatients in 27 states between 1997 and 2014 (

18), and among Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patients between 2002 and 2009 (

19). Limitations of these EHR studies include that the most recent year reported was 2014, that three of the studies covered inpatients only (

16–

18), and that ICD-9-CM was used, which was replaced by ICD-10-CM in 2015. Further, only one study tested for differences between demographic subgroups (

13,

16), finding that in the general population, increases were greater among males, Blacks, and young adults ages 18–29 between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 (

13,

16). More information is needed to identify population subgroups with disparities in risk for cannabis use disorder (

20).

Discussion

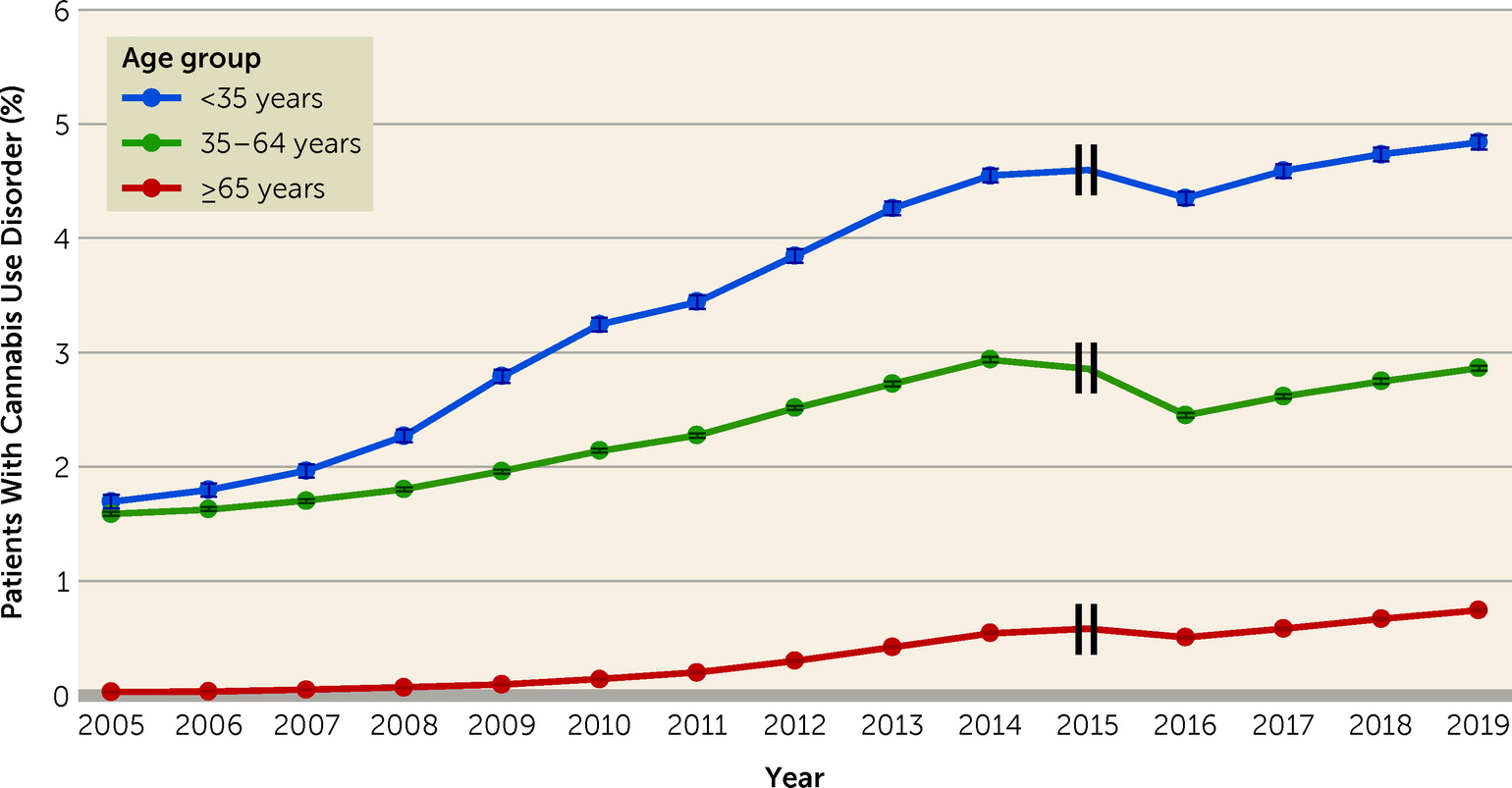

We examined time trends in diagnoses of cannabis use disorder from 2005 to 2019 among patients treated in the VHA. The years examined represent a period of substantial change in the cannabis landscape in the United States, and also the transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM. Cannabis use disorder diagnoses more than doubled overall in the VHA, from 0.85% in 2005 to 1.92% in 2019. Increases were found across age, sex, and racial/ethnic subgroups of patients. The study findings are consistent with other U.S. studies showing increases in the prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder among adults during the past 20 years, including general population surveys (

5,

9,

10,

24) and EHR studies (

16–

19). The present study, which extends findings from an earlier VHA study showing increasing cannabis use disorder diagnoses from 2002 to 2009 (

19), indicates that cannabis use disorder continued to increase. Collectively, these studies indicate increases over time in cannabis use disorder among U.S. adults.

Both cannabis-specific factors and larger societal-level forces could explain the overall increases. One cannabis-specific factor is the increasing perception that cannabis is not a harmful substance (

5–

7). This perception could lead to more users and more cases of cannabis use disorder among these users, given that 20%–33% of cannabis users develop cannabis use disorder (

4). Another cannabis-specific factor is increasing legalization, as suggested by national survey findings on adult cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (

29–

31). Determining whether state legalization of cannabis for medical or recreational use is selectively associated with increased rates of cannabis use disorder among VHA patients is a complex undertaking that is outside the scope of the present study, but this should be done in the future. Yet another cannabis-specific factor is the increasing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol potency of licit and illicit cannabis products (

8,

32,

33), since higher potency predicts increased risk for progression from use to cannabis use disorder symptoms (

34). Further studies of all these factors are needed, including in VHA patients.

Larger societal-level forces could also help explain the overall increases. Cannabis is used for varying reasons and motives, including to cope with stress, which is strongly associated with cannabis use disorder symptoms (

35). The years 2005–2019 were stressful for many Americans, encompassing a major recession and an unequally distributed economic recovery. Fears of economic losses, and actual job loss, could have increased stress, for which cannabis may have been increasingly used to cope, leading to increased prevalences of cannabis use disorder, including among VHA patients, whose socioeconomic level is lower compared to other veterans and to U.S. adults as a whole (

23,

36,

37). Studies are needed to investigate these speculative explanations.

Our findings indicate that, generally, male VHA patients had higher rates of cannabis use disorder diagnoses than females as well as greater increases in cannabis use disorder diagnoses over time (the only exception being patients under age 35 from 2016 through 2019). The general results are consistent with studies in the U.S. general population, one showing that the prevalence of cannabis use increased more among males than females between 2007 and 2014 (

24), and the other showing a wider “gender gap” in adult cannabis use disorder prevalence in 2012–2013 than in 2001–2002 (

13). Speculatively, economic factors may also help explain these trends. Although females consistently earn less on average than males (

38), sex differences in earnings have decreased over time because male incomes have largely stagnated, while female incomes have increased (

39,

40). Increased earnings are clearly advantageous for females, but they could have led to loss of perceived status and self-esteem and increased psychological distress in males, increasing male use of cannabis to cope, and thus greater increases in cannabis use disorder among males than females over time. These factors could have particularly impacted male VHA patients, given their lower socioeconomic level compared to other veterans and other U.S. adults, and the fact that service-related disabilities may have limited their employment opportunities.

The one exception to the greater male increases in cannabis use disorder among VHA patients occurred in the youngest age group (<35 years) in the period from 2016 to 2019, when females had the greater rate of increase. This is consistent with a meta-analysis of birth cohorts showing that the traditional “gender gap” in cannabis use narrowed considerably in recent birth cohorts as a result of greater increases among females than males (

41). This may be due to societal-level changes in norms regarding gender-appropriate behaviors, of which cannabis use is one example. Another reason could be the growing numbers of younger female soldiers exposed to combat in recent wars (

42), leading to increased postdischarge stress in younger female veterans, with accompanying cannabis use and cannabis use disorder.

The results also indicated that Black patients had higher rates of cannabis use disorder than White patients, and that among patients in the 18–34 and ≥65 year age groups, cannabis use disorder diagnoses increased more among Black than White patients (although this was not the case during the earlier period for patients ages 35–64, when rates among Whites increased considerably). The Black/White differences in change that were found are consistent with shifts observed in national surveys. For example, while rates of cannabis use were higher among White adolescents in 1991, this difference had reversed and rates had become higher among Black adolescents by 2018 (

43,

44). In addition, the prevalence of cannabis use disorder was higher among Black than White adults in 2001–2002, a difference that had widened by 2012–2013 (

13). Black individuals face multiple severe stressors, such as interpersonal and structural discrimination and socioeconomic disadvantage that increased between 2005 and 2019 (

45,

46). Perceived racial discrimination predicts subsequent substance use (

47–

49), and structural racism may have similar associations (

50,

51). This could have led to increasingly prevalent cannabis use to cope with stress and consequent cannabis use disorder among Black adults, including VHA patients.

In addition, racial disparities in pain management may have contributed to greater increases in cannabis use disorder among Black VHA patients. In adults in the general population, pain has been shown to be increasingly associated with cannabis use disorder over time (

52). Service-related injuries are common among VHA patients, and over one-third have chronic pain (

53). The VHA has developed a national strategy to deliver safe and effective pain management (

54–

56), and it also emphasizes racial equality in health care (

57). Nevertheless, during the 2005–2019 period of changing cannabis norms and laws, racial disparities in VHA pain management could have led some Black patients to increasingly self-treat pain with cannabis, leading to higher rates of cannabis use disorder within this group. The only studies known to us with information by racial/ethnic group on authorized medical cannabis use or informal self-treatment did not show racial/ethnic differences (

58,

59). However, both studies were based on data that are now nearly a decade old. Considerable attention has recently been devoted to the importance of identifying and addressing racial disparities in medical care and potential consequences of such disparities. Studies are needed to fill the gaps in knowledge about racial/ethnic differences in medical use of cannabis, especially given the increases in rates of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder among Black adults found in this study and others.

We know of no substantive explanation for the 2015–2016 drop in cannabis use disorder diagnoses in the VHA across age, sex, and racial/ethnic groups. This drop did not occur in the general population (

60). However, it coincided with the VHA transition from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM, which presented many challenges for EHR-based health research (

17). Studies of the effects of the transition on rates of medical conditions have been inconsistent (

61,

62). In studies specifically addressing alcohol (

63), opioid (

64), and cannabis use disorders (

65), conducted in hospital (

62–

65) and emergency department patients, the results showed increases rather than decreases in prevalence after the ICD-10-CM transition, attributed to use of the greater number of relevant categories available in ICD-10-CM. However, these studies addressed patients in acute care, not those seen on an ongoing outpatient basis in a large integrated health care system, which is the situation for most VHA patients. In a subset of VHA patients, the ICD-10-CM transition had little effect on 2016 diagnoses of medical conditions, but was followed by decreases in alcohol, drug, and tobacco diagnoses (

62), with no explanation offered.

Seeking to explain the decrease, we considered provider behaviors. VHA medical providers must add ICD codes to the EHR for new conditions and actively remove codes for resolved or remitted conditions. For cannabis use disorder, the definition of remission may be unclear and its occurrence difficult to assess. Thus, during the years that ICD-9-CM was used, active removal of cannabis use disorder diagnostic codes may not have seemed warranted, leaving a diagnosis entered at an earlier time automatically carried forward year-to-year. However, after the ICD-10-CM transition, all ICD-9-CM codes were removed, requiring providers to reenter codes for current conditions into the EHR. If current cannabis use disorder symptoms were not obvious, no code for ICD-10-CM cannabis use disorder would have been entered, resulting in an apparent drop in cannabis use disorder diagnoses. Subsequently, after the VHA completed the transition to ICD-10-CM in 2016, new or clearly continuing cannabis use disorder cases would be entered by providers. As our findings demonstrate, the 4-year ICD-10-CM period was characterized by steady increases in cannabis use disorder diagnoses across age, sex, and racial/ethnic groups, indicating that once the ICD-10-CM transition was completed, cannabis use disorder diagnoses in VHA patients continued to increase.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. VHA patients are not representative of all veterans or all adults. The ICD diagnoses we analyzed were not based on research interviews, but rather on provider diagnoses. Providers are most likely to be aware of and diagnose severe disorders (

14), so mild cases of cannabis use disorder that might have been detected with research interviews could have been missed. While directly interviewing several million patients a year over the time period we covered is not feasible, the use of provider diagnoses in the EHR provides an opportunity to examine change over time in a large population. Our results should be interpreted as potentially representing increases over time in moderate to severe cases of cannabis use disorder (i.e., those most in need of care), but not necessarily increases in mild cases. Another source of potential surveillance bias is the possibility that patients were increasingly treated over time for another condition that was associated with cannabis use disorder, in which case cannabis use disorder diagnoses would have appeared to increase, although the increase would have been artifactual. Additionally, VHA providers may have become increasingly aware of the existence of cannabis use disorder and hence more likely to diagnose it, leading to artifactual but not actual increases in rates. Alternatively, as public attitudes toward cannabis have become more positive, providers may also have changed their views of cannabis, becoming less likely to perceive, diagnose, and note cannabis use disorder in the electronic medical record. This would have led to an artifactual attenuation of any observed increase in cannabis use disorder. The present VHA data sets do not enable us to investigate these possibilities, but in support of our findings, we note their consistency with other national studies, including those not relying on data from treated patients (

9,

12,

24,

66). Another limitation is that the VHA database does not include a variable for cannabis use, so trends in cannabis use disorder diagnoses within users could not be examined.

The study also had notable strengths. These include a large source of data with very large sample sizes across many years, including 4 years of data after the introduction of ICD-10-CM, permitting examination of trends before and after the nomenclature transition. This permitted examination of trends by age, sex, and racial/ethnicity. To our knowledge, this is the first large EHR study to examine trends in cannabis use disorder diagnoses since 2016.

In summary, this study provides important information on increases in cannabis use disorder among VHA patients since 2005. While these trends were found across age, sex, and racial/ethnic subgroups, the increases were especially pronounced among male patients and among Black patients. The VHA offers an extensive and robust array of evidence-based substance use disorder treatments (

25–

27), but updated information on the extent of cannabis use disorders among VHA patients has not been available for many years. Many individuals can use cannabis without harms, and cannabis use does not have the same overdose or mortality risk profile as opioids or cocaine (

67). However, cannabis use disorder is a diagnosable disorder with multiple risks of its own that is now more likely to occur among cannabis users than is commonly assumed (

4). Therefore, information from the present study suggests a growing need for screening and treatment in the VHA for patients with cannabis use disorder. In addition, this study adds to the literature indicating increases in the prevalence of cannabis use disorder among U.S. adults over the past two decades. While an earlier household survey suggested that the increases were largely due to growing numbers of mild cases (

10), the present study of VHA patients, with its reliance on the more severe cases likely to be known to providers and recorded in the EHR, suggests increases in severe cases as well. Evolving cannabis norms, laws, and products, promoted by the growing, multibillion-dollar cannabis industry (

68), may be exerting an upward pressure on cannabis use disorder rates among VHA patients as well as in the general population, leading to a growing public health problem. Clinicians and the public should be educated about this problem, and policy makers should work toward policies that minimize it. Public and professional awareness of the risks (

4), consequences (

3), and increasing prevalence of cannabis use disorder would benefit adults in general, and veterans in particular, including those who receive treatment in the VHA.