In 2022, the APA Joint Reference Committee voted to approve a comprehensive Resource Document jointly sponsored by the APA Councils on Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and Addiction Psychiatry for psychiatrists involved in the treatment of patients with Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) in the general hospital. The full Resource Document, which includes a comprehensive review of the literature, is available in a data supplement that accompanies the online version of this APA Official Action in the August issue of the

American Journal of Psychiatry (

ajp.psychiatryonline.org). The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this Resource Document do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association and do not represent APA policy. The following summary highlights essential concepts.

The morbidity, mortality and cost of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) has increased to dramatic levels, necessitating a call-to-action for health care systems and providers to reassess the approach to treatment of OUD. The inpatient general hospital, where there is often more time and resources for patient engagement, is an important point of entry into the health care system for patients with medical and surgical complications of OUD.

In-Hospital MOUD Initiation and Continuation

Many physicians are hesitant to initiate or continue medication for OUD (MOUD) due to incomplete understanding of Federal prescribing regulations. Any provider approved to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD, either via a filed Notice of Intent (NOI) for exemption for training through SAMHSA or via a DATA2000 waiver, can initiate and maintain buprenorphine monotherapy or buprenorphine/naloxone for a hospitalized patient with OUD. Providers who are not authorized or waivered may continue previously initiated MOUD, including methadone, for patients in the hospital.

Pharmacologic Treatment

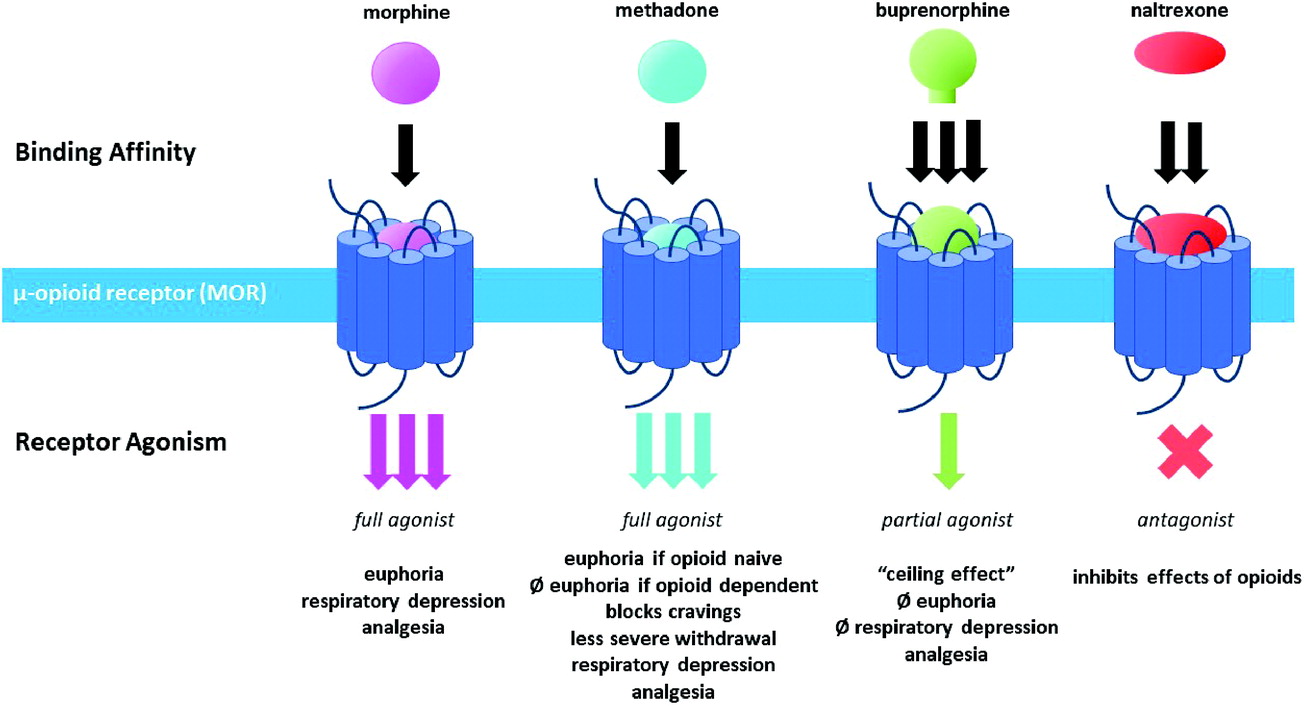

As seen in

Figure 1, buprenorphine is a partial mu-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist with high binding affinity. Since buprenorphine does not fully activate the MOR, it has an improved safety profile compared to other opioids, including less euphoria, decreased abuse liability, and a “ceiling effect” on respiratory depression regardless of the ingested amount. The high binding affinity makes it difficult to displace buprenorphine from the MOR and allows buprenorphine to displace other opioid agonists, which can lead to precipitated withdrawal. Unlike buprenorphine, methadone is a full agonist at the MOR and is not able to precipitate withdrawal. It is important to closely monitor dose titration of methadone as it does not have a “ceiling effect” on respiratory depression like buprenorphine. Methadone is highly lipophilic with a long and variable terminal half-life (5–130 hours), lending itself to once-daily administration for treatment of OUD. The analgesic effects of methadone only last 4–8 hours. Naltrexone is a competitive MOR antagonist available in both oral and intramuscular formulations. The oral formulation is limited by high rates of non-adherence, whereas the injectable version has been shown to be non-inferior to buprenorphine following a medically supervised withdrawal.

Naloxone is a competitive opioid antagonist that displaces opioids and is used to treat opioid overdose. Naloxone is often co-administered with buprenorphine as a single agent, buprenorphine/naloxone. A common misperception about this combined treatment is that the naloxone component will precipitate withdrawal if injected, serving as a deterrent against misuse. However, it is much more likely that buprenorphine will cause withdrawal if injected since it has a higher binding affinity and longer half-life than naloxone.

Perioperative Management

Patients with OUD, including those who are physically dependent on opioids and/or receiving MOUD, are at risk for greater difficulty with pain management in the perioperative period. Current practice favors continuation of home dose buprenorphine and methadone in the peri-operative and acute pain settings with consideration of decreased dosing in certain circumstances. Multi-modal non-opioid analgesia, including acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentin/pregabalin, dexamethasone, lidocaine, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, esmolol, mindfulness relaxation training and regional anesthesia should be optimized when possible. Post-operatively, if pain control is inadequate with non-opioid multi-modal approaches, it is suggested to add full mu-opioid agonists with higher mu opioid receptor affinity, such as fentanyl or hydromorphone, to buprenorphine or methadone. Collaboration between surgery, anesthesia, primary care, OUD-specialists, patient and family is essential.

Transitions of Care

Transition points in care, such as hospital discharges, can be a risky time for many hospitalized patients due to the inherent difficulties finding suitable and timely follow-up care. Bridge clinics provide low-barrier, often harm-reduction focused, continuity of buprenorphine treatment for patients awaiting connection to community care following discharge from the hospital.

Many patients with complex infections may require long-term treatment with parenteral antibiotics. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) is the practice of monitored administration of parenteral antibiotics outside of the hospital setting, usually in a rehabilitation facility, infusion center or in the home. Historically individuals with OUD who inject drugs have been excluded from OPAT due to concerns about illicit injection of drugs via the tunneled catheter. However, a growing body of evidence suggests favorable outcomes of OPAT for people who inject drugs (PWID), especially when there is collaboration between addiction and infectious disease specialists, use of a care navigator or case manager, safe and stable housing, and close patient engagement.

Specialty-Specific Considerations

Hospitalists, internists, infectious disease (ID), cardiology and surgery specialists often encounter patients with OUD who present with blood-borne infections transmitted via injection drug use (IDU) including infectious endocarditis (IE), cellulitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, epidural abscess, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). Unfortunately, nearly a third of PWID leave the hospital prematurely as a patient-centered discharge (i.e., discharge “against medical advice”) without linkage to outpatient OUD treatment or resources to complete antibiotic therapy. Risk factors for premature discharge and non-completion of treatment include stigma, negative interactions with staff, poorly controlled cravings and withdrawal symptoms, poorly controlled pain, restrictive hospital policies that are carceral in nature (e.g., restricting mobility or 1:1 observation), use of illicit drugs in the hospital, and outside psychosocial obligations. For patients at risk for non-completion of parenteral antibiotics there is a growing body of evidence to support use of oral antibiotics, and for some infections the use of long-acting parenteral antibiotics (dalbavancin, oritavancin) administered as a one- or two-time infusion.

Infective Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the heart valves and/or endocardium and a common complication of IDU. Surgical valve repair or replacement is required in 20%–40% of patients with IDU-related IE and many patients will require repeat surgical intervention due to ongoing IDU. Guidelines of The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) for treatment of patients with valvular heart disease recommend consultation with addiction medicine to discuss long-term prognosis for abstention before surgical intervention is considered. Notably, the ACC/AHA guidelines do not comment on provision of substance use disorder treatment for patients with IDU-IE, perhaps due to lack of training and knowledge, misperceptions about feasibility of initiating MOUD in the hospital, lack of outpatient MOUD resources, and ongoing stigma. Policies that require signed contracts declaring abstinence as a requirement for surgery are ineffective and inherently flawed, especially when in most cases the underlying OUD has not been treated.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis C Virus

Injection drug use is now the most common risk factor for acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The provision of MOUD to persons living with HIV (PLH) has had a positive impact on receipt and adherence with antiretroviral treatment (ART), HIV viral suppression, HIV transmission and use of illicit opioids. It is essential to consider drug-drug interactions between ART and MOUD. Buprenorphine has few drug-drug interactions with ART. Efavirenz is a cytochrome p450 inducer of methadone metabolism. Ritonavir is both an inhibitor and inducer of cytochrome p450 isoenzymes that metabolize methadone and as such, careful attention to both respiratory depression and opioid withdrawal is warranted when initiating or changing doses of either medication. Oral and extended-release naltrexone have been shown to have positive safety profiles in PLH, each with minimal hepatotoxicity and no effect on cytochrome P450 metabolism.

Harm Reduction

Injection drug use-related infections can be prevented through implementation of harm reduction strategies, including MOUD. The Harm Reduction Coalition Safety Manual for Injection Drug Users “Getting Off Right” (

https://harmreduction.org/issues/safer-drug-use/injection-safety-manual/) is a comprehensive and high-yield resource for both PWID and clinicians that provides instructions for safest injection practices including choosing materials, drug preparation, injection techniques, and management of health complications and overdose.

Pregnancy

Pregnant patients with OUD face heightened stigma, often operationalized with punitive practices under the guise of “protecting” the fetus from opioid exposure. Many states consider illicit substance use during pregnancy to be reportable as child abuse or neglect. Unfortunately, fear of legal consequences has not been a motivator for pregnant women to cease use of illicit drugs; rather, it is a barrier that may drive women from seeking or continuing care, leading to increased risk of adverse outcomes for the mother-infant dyad.

In 2018, ACOG and SAMHSA published joint guidelines for the care of pregnant women with OUD (

https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma18-5054.pdf). Pregnant women should be offered treatment with methadone or buprenorphine. Medically supervised withdrawal during pregnancy is associated with a high rate of return to substance use and is not recommended. During labor and delivery, the daily dose of methadone or buprenorphine should not be expected to provide analgesia, nor should doses be increased to control pain. The use of epidural and/or short-acting opioids including morphine sulfate, fentanyl and hydromorphone are appropriate analgesic options. Breastfeeding is recommended for women stable on buprenorphine and methadone as drug levels are very low in breastmilk.

Culture Change Through Day-To-Day Liaison Work

Stigma against patients with mental health and substance use disorders is pervasive and increases as perceived cause and control over one’s own condition increases. Structural stigma at the institutional level, often reflecting the belief that people with substance use disorders may be less treatable and less deserving of care, may influence organizational policies and resource allocation. Many institutional policies treat SUDs as a criminal issue rather than a health concern. Punitive policies that have inherent carceral association include the need for repeat urine tests, safety sitters, security presence, observed changing from street clothes to hospital supplied attire, denied access to personal belongings, and holding of home methadone or buprenorphine doses until confirmed by an outside provider, among others. Internalized or self-stigma, which can manifest as a sense of shame, worthlessness, and being undeserving of care, can result in alienation, disempowerment and ultimately disengagement from care.

Many strategies can be used to combat stigma against mental health and substance use disorders. Increased education about the evolutionary neurobiological mechanisms of addiction can help shift blame from the individual, mitigating the widespread belief that opioid seeking behaviors are solely under the individual’s volition. Highlighting patient success stories and involving individuals with lived experience can be an effective strategy to bridge the gap between health care providers and patients with OUD. Recruiting service-level champions to empower staff with knowledge, the belief that OUD is a treatable disease, and modeling of non-stigmatizing language (e.g., having a “urine test positive for opioids,” versus “a dirty urine”) is essential.

Vulnerable Populations and Trauma-Informed Care

Marginalized and vulnerable groups less likely to be prescribed MOUD include Black, Latinx, Alaska Native/American Indian, LGBTQIA+, women, immigrants, rural and older adult populations. It is essential for providers of MOUD to be aware of and inquire about sociocultural factors that may influence prevention, treatment and recovery, including language barriers, trauma, minority stress, immigration status, transportation, shame and stigma. Prior trauma is highly prevalent in patients with OUD and can impact clinical outcomes, necessitating the universal application of trauma-informed care principles.