Diagnosis

About 80% of women report at least mild premenstrual symptoms, 20%–50% report moderate-to-severe premenstrual symptoms, and about 5% report severe symptoms for several days with impairment of functioning (

1). The 5% of women with the severest premenstrual symptoms and impairment of social and role functioning often meet the diagnostic criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). The diagnostic criteria for PMDD are listed in the appendix of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (

1), and women who meet criteria for PMDD receive a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis code 311 (i.e., depressive disorder not otherwise specified). To meet the PMDD criteria, at least 5 of 11 possible symptoms must be present in the premenstrual phase, these symptoms should be absent shortly after the onset of menses, and at least 1 of the 5 symptoms must be depressed mood, anxiety, affective lability or irritability. Other symptoms include decreased interest in usual activities, difficulty concentrating, low energy, changes in appetite, changes in sleep, a sense of being overwhelmed or out of control, headaches, joint or muscle pain, breast tenderness or swelling and abdominal bloating (

1). Women with fewer or less severe symptoms are considered to have premenstrual syndrome (PMS). The

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Practice Guidelines (

2) and the

International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (

3) both suggest diagnostic criteria for PMS that require a minimum of 1 premenstrual symptom.

Prospective daily rating of the PMDD criteria symptoms over 2 menstrual cycles is required to confirm the PMDD diagnosis. The daily ratings should document the timing of the symptoms during the premenstrual phase and the absence of symptoms or a chronic underlying disorder during the follicular phase. The retrospective reporting of premenstrual symptoms may amplify the woman's recall of the severity and frequency of symptoms. Reporting of symptoms can be influenced by the phase of the menstrual cycle when queried, the phrasing of questions, expectations and cultural issues (

4). Studies conducted over the past 2 decades have used various scoring methods and different instruments for daily ratings to measure the premenstrual increase of symptoms. Recent studies have used visual analog scales (

5) and Likert scale daily rating forms such as the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (

6) or the Penn Daily Symptom Report (

7). Various scoring methods compare the average of symptom scores during the premenstrual days with the average of symptom scores postmenses. The DSM-IV-TR PMDD criteria state that the premenstrual symptoms should not be an exacerbation of an underlying disorder but that PMDD could be superimposed on an axis I or II disorder (

1).

Epidemiology

Three studies in which subjects prospectively rated their symptoms reported PMDD prevalence rates of 4.6%–6.4% (

8–

10). Two studies of women who retrospectively rated their premenstrual symptoms according to PMDD criteria reported similar prevalence rates of 5.1%–6.7% (

11,

12). These 2 studies reported that 18.6%–20.7% of women have “subthreshold PMDD,” in which the full criteria are not met because they have fewer than 5 symptoms or because they fail to meet the functional impairment criterion. Even though premenstrual symptoms are described in women from menarche to menopause, it is unclear whether symptoms remain stable or increase in severity with age (

12,

13). Irritability has been identified as the most common premenstrual symptom in US and European samples (

13–

15). Some cultures emphasize somatic rather than emotional premenstrual symptoms (

16). Symptom severity peaks on or just before the first day of menses (

4,

10,

15). Studies examining age, menstrual cycle characteristics, cognitive attributions, socioeconomic variables, lifestyle variables and number of children have not identified these variables as predisposing factors (

13,

17). An elevated lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) in women with PMDD has been reported in several studies, (

18) as has an elevated lifetime prevalence of postpartum depression (

19).

A recent study is the first to demonstrate allelic variation on the estrogen receptor α gene in women with PMDD when compared with control women (

20). In addition, the allelic variation was only significant in women who had a valine/valine genotype for the catechol-

O-methyltransferase enzyme. This significant study may identify a source of abnormal estrogen signalling during the luteal phase that leads to premenstrual affective, cognitive and somatic symptoms (

20). Previous studies had failed to identify gene polymorphism differences between women with PMDD and control subjects in regard to the serotonin transporter (

21,

22), the transcription factor activating protein 2 (

23), tryptophan hydroxylase and monoamine oxidase A promoter (

22) genes. Overlap of PMDD with genetic liability for MDD, seasonal affective disorder and personality characteristics has been suggested (

24,

25).

The diagnosis of PMDD requires the confirmation of luteal-phase impairment of social and/or work functioning that is due to premenstrual symptoms. The functional impairment reported by women with PMDD is similar in severity to the impairment reported in MDD and dysthymic disorder (

26,

27). One study identified anxiety, irritability and mood lability as the premenstrual symptoms most associated with functional impairment (

28). The burden of illness of PMDD results from the severity of symptoms, the chronicity of the disorder and the impairment in work, relationships and activities (

29). It has been estimated that women with PMDD cumulatively endure 3.8 years of disability over their reproductive years (

26). A study of 1194 women who prospectively rated their symptoms reported that women with PMDD were more likely to endorse hours missed from work, impaired productivity, role limitations and less effectiveness (

30). Borenstein and colleagues (

31,

32) have published studies examining functioning and health service use in 436 women who prospectively charted their symptoms for 2 cycles. Women with confirmed PMS reported significantly lower quality of life, increased absenteeism from work, decreased work productivity, impaired relationships with others and increased visits to health providers, compared with control women. These authors also reported that, given a 14% absenteeism rate and a 15% reduction in productivity, PMDD was associated with US$4333 indirect costs per patient per year (

33). The economic burden associated with PMDD is more related to self-reported decreased productivity than to direct health care costs (

30,

33). However, women with PMDD do report increased health services use, with visits to health care providers and use of prescription medications and alternative therapies (

30,

32). Small studies of women with prospectively confirmed PMDD have also reported decreased interpersonal and work functioning and reduced quality of life in comparison with women without PMDD (

34–

36). Larger studies of women diagnosed retrospectively according to PMDD criteria have also reported substantial functional impairment in work and interpersonal roles (

11,

12,

37,

38).

Differential diagnosis

Because most PMDD symptoms are affective or anxiety-related, PMDD should generally not be diagnosed when an underlying depression or anxiety disorder is present; many such women are considered to have premenstrual exacerbation of their underlying depression or anxiety disorder. A recent study reported that 64% of the first 1500 women with MDD enrolled in the STAR*D study retrospectively reported premenstrual exacerbation of their depressive symptoms (

39). Dysthymia, MDD, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are the most common axis I psychiatric disorders that may be concurrent and exacerbated premenstrually, with less clear evidence for bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, social phobia, eating disorders and substance abuse (

12,

18,

40–

43). Personality disorders do not have elevated prevalence in women with PMDD (

19), but women with PMDD and a personality disorder may demonstrate premenstrual phase amplification of personality dysfunction (

44). Schizophrenia may be an example of an underlying disorder that does not have premenstrual exacerbation of psychotic symptoms but may have superimposed affective and anxiety symptoms of PMDD (

45). The prevalence of premenstrually exacerbated axis I disorders is unknown. It is generally recommended that clinicians treat the underlying disorder first, and if premenstrual symptoms persist, subsequent daily ratings can identify PMDD (

46).

Symptoms of endometriosis, polycystic ovary disease, thyroid disorders, adrenal system disorders, hyperprolactinemia and panhypopituitarism may mimic symptoms of PMS. Medical disorders that may demonstrate a premenstrual increase in symptoms include migraines, asthma, epilepsy, irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes, allergies and autoimmune disorders (

42,

47). It is presumed that the menstrual cycle fluctuations of gonadal hormones influence some of the symptoms of these medical conditions.

Etiology

Several reviews exist of pathophysiological hypotheses of PMS and PMDD and the evidence for them (

48–

52). Most studies do not identify consistent abnormalities in hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, although a few studies have suggested altered luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse (

53). As well, studies have not identified clear abnormalities in thyroid hormones, cortisol, prolactin, glucose, prostaglandins, β-endorphins, vitamins or electrolytes (

49,

50). Since specific abnormalities in the HPG axis have not been identified in women with PMDD when compared with control subjects, it is thought that premenstrual symptoms occur as a result of a differential sensitivity to the mood-perturbing effects of gonadal steroid fluctuations in women with PMS and PMDD (

54). It is probable that the etiology of the “differential sensitivity” is multifactorial and in part genetically determined (

55). The recently identified allelic variation in the estrogen receptor α gene in women with PMDD may underlie the neurotransmitter and neuropeptide differential sensitivity owing to estrogen receptor influence on synthesis, receptors, transporters and cell signalling (

20).

Although the specific neurotransmitter, neuroendocrine and neurosteroid abnormalities in women with PMDD are not known, serotonin, norepinephrine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), allopregnanolone (ALLO, an anxiolytic metabolite of progesterone that acts at the GABA

A receptor), endorphins and factors involved in calcium homeostasis may all be involved. Women with PMDD are more sensitive to the anxiogenic properties of carbon dioxide inhalation, lactate infusion, cholecystokinin tetrapeptide and flumazenil (

49). Increased adrenergic receptor binding may reflect abnormal noradrenergic function (

49). Women with PMDD have abnormal melatonin secretion and other circadian system abnormalities (

56). It has been proposed that women with PMDD have altered affective information processing and regulation during the luteal phase, with abnormal activation patterns in specific brain regions (

55). Imaging studies have demonstrated altered functional magnetic resonance imaging responses to negative and positive stimuli in the orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala and ventral striatum in women with PMDD compared with control subjects (

57). A recent study reported significantly increased negative bias in the recognition of emotional facial expressions during the luteal phase in women with PMDD when compared with control women (

58).

Many studies have identified various abnormalities in the serotonin system in women with PMS and PMDD. These include abnormal levels of whole blood serotonin, serotonin platelet uptake and platelet tritiated imipramine binding; abnormal responses to serotonergic probes such as

l-tryptophan, buspirone, metachlorophenylpiperazine and fenfluramine; and exacerbation of premenstrual symptoms after metergoline or tryptophan depletion (

49,

51,

59). Several studies have also suggested that women with PMDD have decreased luteal-phase levels of GABA, abnormal ALLO levels and decreased luteal-phase sensitivity of the GABA

A receptor, as shown by flumazenil challenge and the sedative and saccadic eye velocity responses to benzodiazepines and alcohol (

48,

49,

52,

60). Imaging studies have reported altered serotonin function (

61,

62) and altered GABAergic function (

63,

64) in women with PMDD when compared with healthy control subjects. It is possible that the rapid efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in PMDD may be due in part to their ability to increase ALLO levels in the brain and enhance GABA

A receptor function (

65). Alternative hypotheses for the fast action of SSRIs in PMDD include enhanced function of 5-HT

2C receptors (

66) and inhibition of the serotonin transporter with resulting decreased LH production (

67). It has also been hypothesized that the increase in ALLO after SSRI administration underlies the improvement in depressive symptoms of MDD in both sexes (

68–

70).

Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OCs) have been commonly prescribed by gynecologists and primary care clinicians for the treatment of PMS even though there were few studies demonstrating their efficacy until recently. Two older randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in samples of women with prospectively confirmed PMS reported a lack of efficacy with monophasic and triphasic OCs (

72,

73). Surveys of population cohorts without defined PMS or PMDD have reported that OCs do not alter mood in most women, but a subset of women report improvement of premenstrual symptoms, and another subset of women report the production of negative premenstrual symptoms (

74,

75). After the introduction in the late 1990s of an OC containing ethinyl estradiol 30 μg and a unique progesterone, drospirenone 3 mg, improved mood and quality of life during the luteal phase began to be reported in nonclinical population cohorts (

60,

76,

77). In addition, a 6-month extended regimen of this OC was reported to be associated with fewer premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms than the normal 21/7 monthly administration in women not seeking care for problematic premenstrual symptoms (

78). An RCT comparing the OC containing ethinyl estradiol 30 μg and drospirenone 3 mg with placebo in 82 women with PMDD reported that both the OC and placebo improved most premenstrual symptoms and that the OC was significantly more effective than placebo in decreasing food cravings, increased appetite and acne only (

79). However, 2 recent studies of YAZ (Bayer HealthCare), an OC containing ethinyl estradiol 20 μg and drospirenone 3 mg, administered as 24 days of active pills followed by a 4-day hormone-free interval (24/4), have reported superiority in reducing premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms when compared with placebo (

80,

81).

Yonkers and colleagues (

80) reported on a parallel design study in which YAZ or placebo was administered to 450 women with PMDD over 3 months. Pearlstein and colleagues (

81) reported on a crossover design study in which YAZ or placebo was administered to 64 women with PMDD over 7 months with a middle washout cycle. Both studies reported that self-rated symptom, functioning and quality of life measures, along with clinician-rated symptom and functioning measures, all significantly improved with YAZ in comparison with placebo. In both studies, adverse effects that were more common with YAZ, compared with placebo, included nausea, intermenstrual bleeding and breast pain (

80,

81). In 2006, YAZ received United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of PMDD in women desiring oral contraception. The efficacy of this particular OC for reducing premenstrual symptoms may be due to its administration in a 24/4 regimen, which provides more stable hormone levels and reduces adverse symptoms that can occur during withdrawal bleeding (

82,

83). Differential efficacy of this OC may also be due to the unique antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic properties of drospirenone (

77,

80,

81).

Other ovulation suppression treatments

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists suppress ovulation by downregulating GnRH receptors in the hypothalamus, leading to decreased follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH release from the pituitary resulting in decreased estrogen and progesterone levels. GnRH agonists are administered parenterally (e.g., subcutaneous monthly injections of goserelin, intramuscular monthly injections of leuprolide, daily intranasal buserelin). GnRH agonists have been reported to be superior to placebo in 8 of 10 published RCTs in women with PMS or PMDD (

48,

84). A meta-analysis of 5 of these studies reported an odds ratio of 8.66 that GnRH agonists will lead to improvement in premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms, compared with placebo (

85). “Add-back” hormone strategies have been investigated to counteract the undesirable medical consequences of hypoestrogenism resulting from prolonged anovulation induced by GnRH agonists. The meta-analysis concluded that add-back estrogen and progesterone did not reduce the efficacy of GnRH agonists (

85) even though it had been reported that the add-back of estrogen and progesterone to goserelin (

86) and leuprolide (

54) led to the reappearance of mood and anxiety symptoms in some women with severe PMS. Since women with severe PMS and PMDD have an abnormal response to normal hormonal fluctuations (

54), it is not a surprise that some women may experience the induction of mood and anxiety symptoms from the addition of gonadal steroids, which reduces the benefit of the replacement strategy. Suggested replacement strategies have also included low-dose pulsed progesterone (

87) and tibolone, a synthetic steroid with estrogenic, androgenic and progestogenic properties (

88). The safety of the long-term use of GnRH agonists and replacement hormones is unknown.

Oophorectomy and prolonged anovulation from danazol, estrogen or progesterone administered throughout the cycle are not common treatments, largely because of the medical risks attendant on a prolonged hypoestrogenic state, which leads to the same long-term health issues as those arising from use of GnRH agonists. Danazol, a synthetic steroid, alleviates premenstrual symptoms when administered at dosages that induce anovulation (200–400 mg/d) (

89). When danazol 200 mg daily was administered during the luteal phase only, which did not lead to anovulation, breast tenderness improved, but other premenstrual symptoms did not improve (

90). The few studies on estrogen or progesterone administered for most of the cycle have yielded mixed reports (

48,

91). Two small studies reported relief of intractable PMS with hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy (

92,

93). Hysterectomy with oophorectomy should be considered a last-resort treatment option for women with severe PMDD that has not responded to standard treatments (

94,

95).

Antidepressant medication

Treatment studies of SSRIs and PMDD have suggested efficacy rates similar to those found in treatment studies of SSRIs and MDD, with 60%–70% of women responding to SSRIs in comparison with about 30% of women responding to placebo, depending on how response is defined (

71,

98). The SSRI dosages that are effective for PMDD are similar to or slightly lower than the dosages recommended for the treatment of MDD. A systematic review of RCTs of SSRIs reported that, compared with placebo, women with severe PMS or PMDD were about 7 times more likely to respond to SSRIs (

99,

100). This review included 12 trials with continuous dosing (daily for the full cycle) of fluoxetine (

101–

107), sertraline (

108,

109), paroxetine (

110), citalopram (

111) and fluvoxamine (

112) and 4 trials with intermittent dosing (daily during the luteal phase, i.e., from ovulation to menses only) of sertraline (

113–

115) and citalopram (

111). The systematic review of these 15 studies concluded that continuous and intermittent dosing had equivalent efficacy (

99). Since this systematic review, one study of 167 women with severe PMS and PMDD reported that continuous and intermittent dosing of sertraline had equivalent efficacy and that each was superior to placebo (

116). However, another study of 167 women with PMDD recently reported that, although both continuous and intermittent paroxetine were both superior to placebo for irritability, affect lability and mood swings, intermittent paroxetine was less effective than continuous paroxetine for depressed mood, low energy, food cravings and somatic premenstrual symptoms (

117). A recent meta-analysis of 29 SSRI studies in 2964 women concluded that continuous dosing is more effective than intermittent dosing for treatment of PMS and PMDD (

118).

The seminal studies involving continuous dosing of SSRIs in PMDD involved relatively large samples. One RCT compared fluoxetine 20 mg daily, fluoxetine 60 mg daily and placebo in 277 women over 6 months (

101). Both fluoxetine 20 mg daily and 60 mg daily were more efficacious than placebo in reducing premenstrual emotional, behavioural and physical symptoms; however, the 20-mg dosage was better tolerated than the 60-mg dosage. This study was one of the first to note a fast onset of action and improvement in physical premenstrual symptoms with an SSRI (

101). Another large RCT involved flexible-dose sertraline, up to 150 mg daily, over 3 months, and the average dose of 110 mg daily was more effective than placebo in reducing premenstrual symptoms (

108) and improving psychosocial functioning in 243 women (

27). Since this review, 2 large RCTs have demonstrated that, when compared with placebo over 3 months, continuous dosing of paroxetine controlled release (CR) 12.5 mg or 25 mg daily had superior efficacy in reducing premenstrual mood and physical symptoms in 313 (

119) and 359 (

120) women with PMDD. In both studies, paroxetine CR 25 mg daily was more effective than 12.5 mg daily in the improvement of premenstrual functioning and the reduction of premenstrual physical symptoms.

RCTs conducted subsequent to the review by Dimmock and colleagues (

99) have also further established the efficacy of intermittent dosing of fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine. Luteal-phase fluoxetine 20 mg daily was superior to placebo in reducing premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms in 252 women with PMDD, whereas fluoxetine 10 mg daily during the luteal phase only was superior to placebo in reducing emotional but not physical symptoms (

121). An RCT in 200 women with PMDD demonstrated that luteal-phase sertraline 50–100 mg daily was superior to placebo for improving premenstrual emotional symptoms and impaired functioning but not premenstrual physical symptoms (

122). Another RCT, in 366 women with PMDD, reported that luteal-phase dosing of both paroxetine CR 12.5 mg and 25 mg daily was superior to placebo in reducing premenstrual symptoms and improving functioning (

123). Studies involving intermittent dosing have reported the absence of discontinuation symptoms when fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine CR at the given dosages were abruptly stopped on the first day of menses. It has been hypothesized that the lack of withdrawal effects when the SSRI is discontinued at menses may be due to the lack of prolonged exposure (

98). Even when the SSRI is abruptly discontinued on the first day of menses, the therapeutic action of intermittent dosing continues to relieve symptoms that extend into the first few days of menses (

124). The FDA has approved the use of both continuous and intermittent dosing of fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine CR for women with PMDD, with specific dosage recommendations (

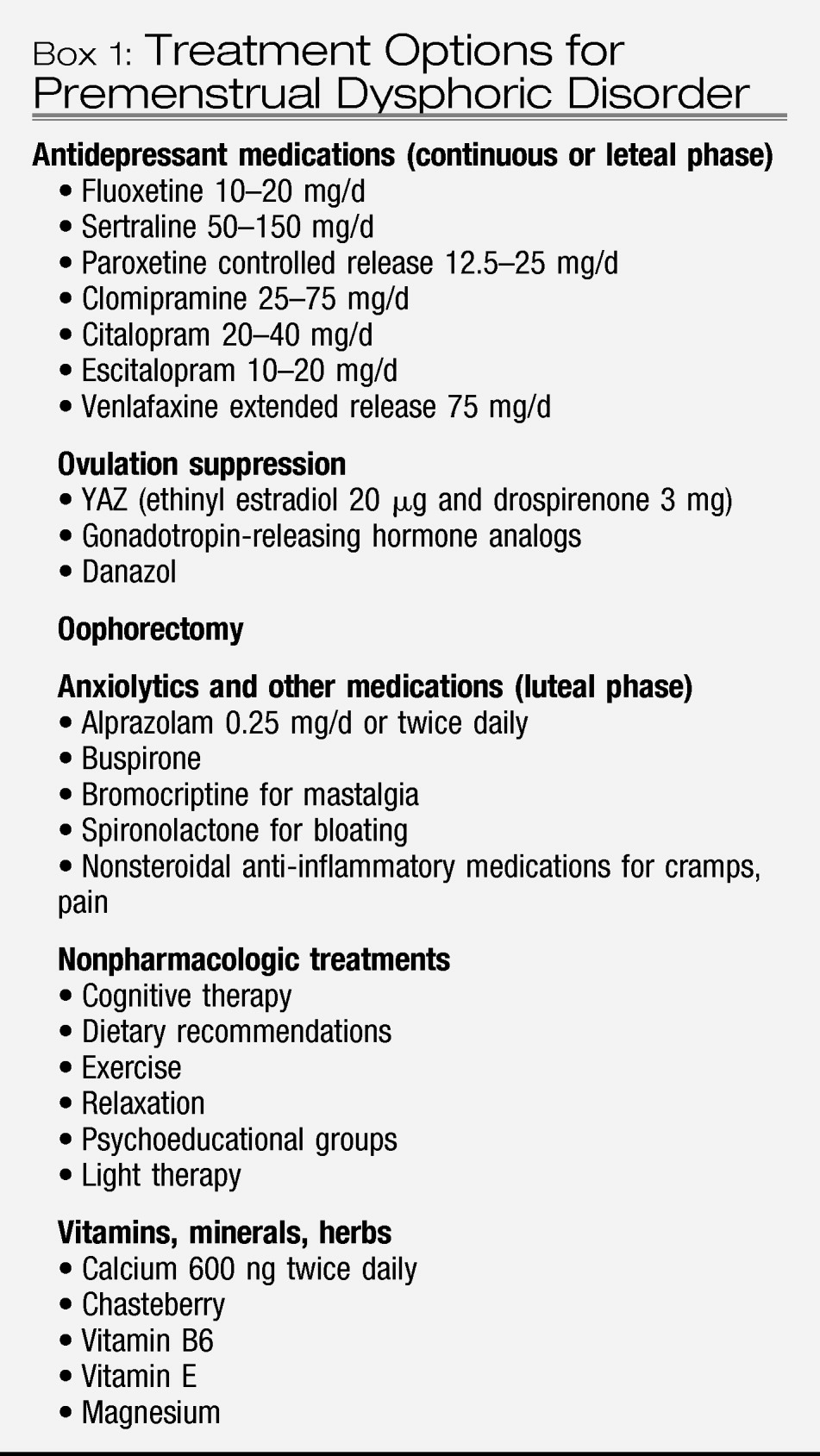

Box 1). The first placebo-controlled RCT conducted with escitalopram recently reported that intermittent dosing with escitalopram 20 mg daily was superior to placebo in 158 women with PMDD (

125).

The improvement of symptoms within the first treatment cycle in most continuous-dosing SSRI trials, as well as the efficacy of intermittent dosing, suggests a more rapid and different mechanism of action for SSRIs in PMDD as compared with MDD, where SSRIs may take 3–6 weeks to be effective. An increase in ALLO is one hypothesis to explain the rapid improvement of premenstrual symptoms with SSRIs. If an increase in ALLO is what makes an SSRI helpful for reducing symptoms, it may not be necessary to start the SSRI before or at ovulation. The few studies that have examined SSRI administration during the luteal phase, but after ovulation, have yielded mixed results. One study suggested that the administration of an SSRI the second luteal week only was not sufficient for efficacy. Fluoxetine 90 mg administered once 1 week before the expected onset of menses was not superior to placebo, but fluoxetine 90 mg administered 2 weeks and 1 week before the expected onset of menses was reported to be superior to placebo in reducing premenstrual emotional symptoms and improving premenstrual functioning but not premenstrual physical symptoms in 257 women with PMDD (

126). Recently published RCTs have reported the efficacy of SSRIs for symptom-onset dosing of SSRIs, that is, administering SSRIs from the postovulatory day that premenstrual symptoms appear until menses. Preliminary studies in women with PMDD have suggested the superiority of symptom-onset paroxetine when compared with placebo (

127) and the efficacy of both symptom-onset and luteal-phase escitalopram dosing, although luteal-phase dosing was found to be more effective for women with severe symptoms (

128). Symptom-onset dosing of low-dose sertraline (25–50 mg/d) was reported to be superior to placebo in reducing premenstrual symptoms in 296 women with prospectively confirmed PMS (

129).

Other antidepressants have also been studied in women with PMS and PMDD. Early RCTs reported efficacy with clomipramine (a tricyclic antidepressant with largely serotonergic action) in daily dosing (

130) and in luteal-phase dosing (

131). The dosages of clomipramine reported to be effective for PMS (25–75 mg/d) are lower than the expected effective doses for MDD. Daily dosing of immediate-release venlafaxine was reported to be superior to placebo in the reduction of the emotional and physical symptoms of PMDD in 157 women (

132). One RCT reported that nefazodone was not superior to placebo for PMS (

133). However, in a small crossover study, increasing nefazodone in the luteal phase was reported to improve premenstrual exacerbation of MDD (

134). Three RCTs have compared SSRIs to nonserotonergic antidepressants and placebo, and each has reported specific efficacy of the SSRI over both placebo and the nonserotonergic antidepressant. Sertraline was compared with desipramine and placebo in 167 women with severe PMS or PMDD (

109). Two smaller studies compared paroxetine to maprotiline and placebo (

110) and fluoxetine to bupropion and placebo (

107). The selective superiority of serotonergic antidepressants for PMDD is compatible with the postulated serotonin dysfunction in PMDD.

Many women report the recurrence of premenstrual symptoms after SSRI discontinuation, and many women choose to take SSRIs over the long term. Most SSRI trials have been 3 months in duration, and although a few open studies suggest maintenance of SSRI efficacy over 1–2 years, evidence-based long-term treatment recommendations do not exist. Studies are needed to identify whether or not some women develop tolerance to the SSRI over time, necessitating increases in dosage or switch to another medication, and whether or not some women stay in remission for a period of time after SSRI discontinuation. The short duration of most treatment studies has also not yielded information about potential adverse effects with long-term SSRI use. Anecdotally, many women report weight gain and sexual dysfunction after long-term antidepressant use for PMDD. Intermittent dosing may improve sexual function during the weeks that the SSRI is not taken, but it is not clear whether or not there is less weight gain with intermittent dosing. Systematic studies are needed of semi-intermittent dosing (‘bumping up’) of SSRIs in women with premenstrual exacerbation of an underlying depressive or anxiety disorder. In these women, the SSRI dosage is increased during the luteal phase and decreased back to the usual dosage at menses (

46). Future studies are also indicated to systematically compare the efficacy and predictors of response to symptom-onset, luteal-phase and continuous daily SSRI dosing in women with PMDD.

Lifestyle modifications and psychosocial treatments

Lifestyle modifications that may alleviate premenstrual symptoms can be obtained through self-help materials or professional-led psychoeducation programs. A 4-session group intervention over 18 weeks emphasizing diet, exercise and a positive reframing of a woman's perceptions of her menstrual cycle was superior to a control condition in reducing premenstrual symptoms (

147). In another intervention, 4 weekly peer support and professional guidance groups that included diet and exercise changes, environment modification, self-monitoring and other cognitive techniques were reported to be superior to a waitlist control condition in reducing premenstrual symptoms (

148). It is unclear which lifestyle modifications are most helpful because few studies have been conducted on specific lifestyle modifications or psychosocial treatments.

Common dietary recommendations include increased consumption of complex carbohydrates, frequent snacks or meals, reduced consumption of refined sugar and artificial sweeteners and decreased caffeine intake. It is hypothesized that the ingestion of complex carbohydrates may maintain a steady serum glucose level that may decrease premenstrual food cravings and increase the availability of tryptophan in the brain for serotonin synthesis (

84). Two RCTs that compared a beverage containing simple and complex carbohydrates with an isocaloric placebo beverage that did not increase tryptophan availability reported that the beverage containing simple and complex carbohydrates was superior in reducing premenstrual dysphoria and other symptoms (

149,

150). These 2 studies are the only published RCTs of a specific dietary regimen.

Cognitive therapy (CT) is consistently reported to be an effective treatment for women with PMS. Two studies in women with prospectively confirmed PMS reported superiority of individual CT for reducing premenstrual symptoms when compared with a waitlist control condition (

151) and when compared with information-focused therapy (

152). Another RCT examined the relative efficacy of fluoxetine 20 mg daily, 10 individual CT sessions or their combination in women with PMDD (

153,

154). Efficacy rates at 6 months were comparable between the 3 treatments; however, at 1 year women who had received CT were coping better than those who had received fluoxetine alone. Relaxation has had little systematic study in PMS; a single RCT reported that relaxation therapy was superior to both symptom charting and leisure reading (

155). Exercise has not yet been tested in a sample of women with PMS or PMDD, but it is a frequently recommended treatment. Negative affect and other premenstrual symptoms improve with regular exercise in women in general (

156,

157). Both aerobic and nonaerobic exercise may be helpful.

Dietary supplementation

Calcium 600 mg twice daily was compared with placebo in 466 women with PMDD (

158). Calcium was reported to have a 48% efficacy rate for reducing premenstrual emotional and physical symptoms (except for fatigue and insomnia), compared with 30% for placebo. However, women with concurrent psychiatric illness were not clearly excluded and concurrent medications were allowed, except for analgesics. The efficacy of calcium was somewhat reduced in women who were taking OCs. The results of this study were notable, and calcium deserves further study.

A review of early studies of vitamin B

6 reported a lack of efficacy for PMS (

159). A meta-analysis of 9 controlled trials that included 940 women with PMS indicated only weak support for the efficacy of vitamin B

6 (50–100 mg/d) in reducing premenstrual symptoms (

160). A recent study reported that 80 mg daily of pyridoxine was superior to placebo in relieving anxiety and mood premenstrual symptoms but not physical symptoms (

161). Two small RCTs have suggested the efficacy of magnesium (

162,

163), but other studies have failed to document magnesium deficiency in women with PMDD or improvement of premenstrual symptoms with supplemental magnesium when compared with placebo (

164). An RCT reported superior efficacy for trytophan, compared with placebo, in women with PMDD (

165), and an early study that suggested efficacy for vitamin E deserves replication (

166). Some trials have been conducted with multinutrients containing several vitamin and mineral components. Several of the supplements contained quantities of vitamins that exceeded daily recommended levels, and as reviewed, results from these studies have been mixed (

167,

168). Physical premenstrual symptoms have been reported to improve with fish oil (

169) and soy isoflavones (

170).

Herbal, complementary and other treatments

Reviews of complementary treatments have reported that the strongest evidence exists for the benefit of chasteberry, or

V. agnus castus (

168,

171–

174). It has been hypothesized that the benefit of chasteberry for premenstrual symptoms could be due to its being a dopamine agonist that possibly reduces FSH or prolactin levels (

174). Chasteberry was recently reported to reduce premenstrual symptoms in an open study of 118 women with PMDD (

175). Chasteberry and fluoxetine were both reported to be effective in an RCT of 41 women with PMDD; however, fluoxetine was better for emotional symptoms and chasteberry was better for physical symptoms (

176). The evidence-based reviews concluded that RCTs have not suggested consistent benefit for

Ginkgo biloba, evening primrose oil and homeopathic treatments but that initial positive RCTs suggest further study of massage (

177), reflexology (

178), chiropractic manipulation (

179) and biofeedback (

180). Small RCTs have reported that saffron (

181) and Qi therapy (

182) were each superior to placebo in women with prospectively confirmed PMS. There have been positive open reports, but no RCTs, with

Hypericum (

183,

184), yoga (

185), guided imagery (

186), photic stimulation (

187) and acupuncture (

188). It has been proposed that sleep deprivation and light therapy may decrease premenstrual dysphoria by correcting abnormal circadian rhythms found in women with PMDD (

56). Although a crossover study reported that evening bright light for 2 premenstrual weeks decreased depression and tension (

189), a meta-analysis of the few existing trials suggested a small effect size for bright light therapy (

190).