Internal Criteria

As

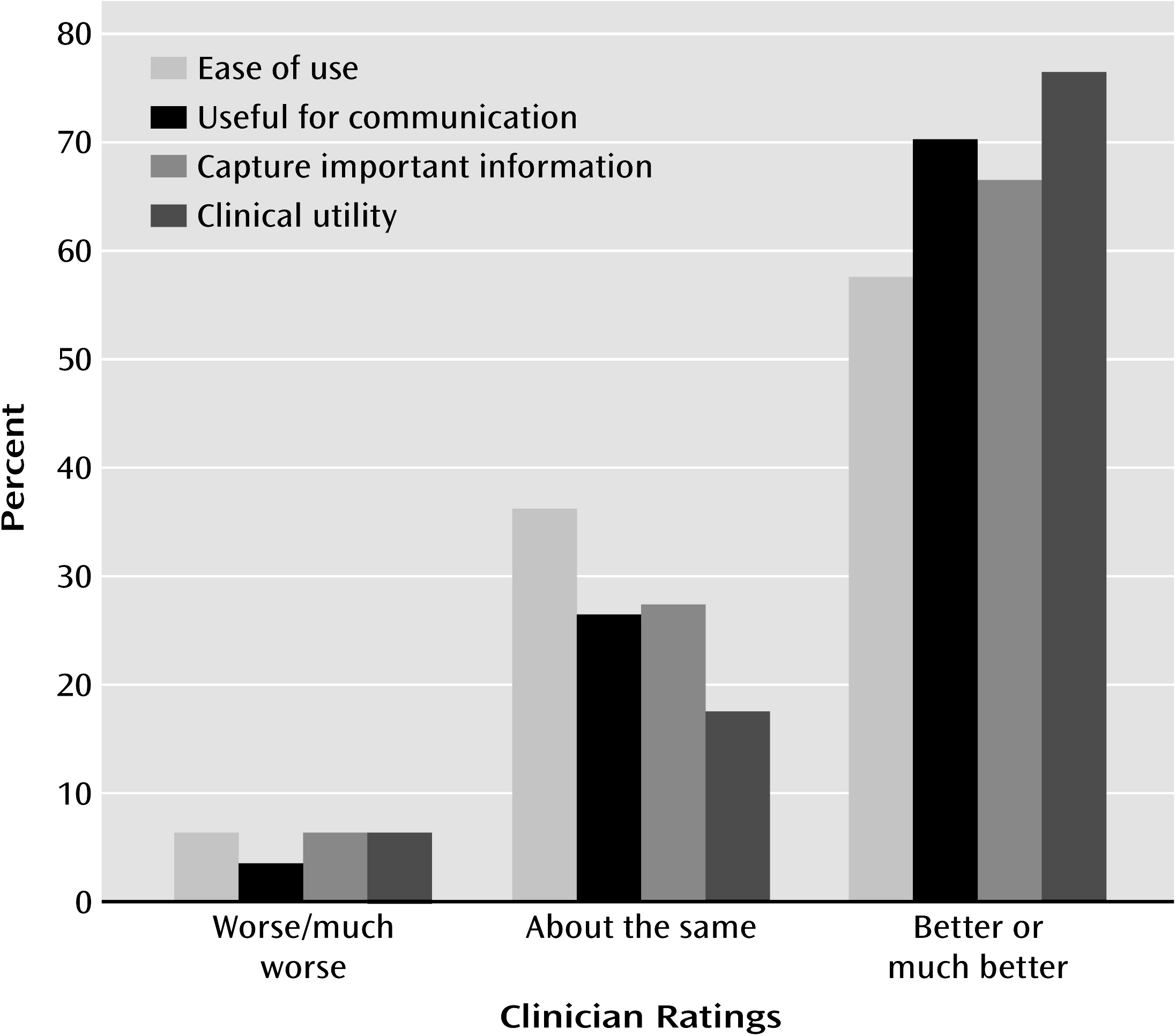

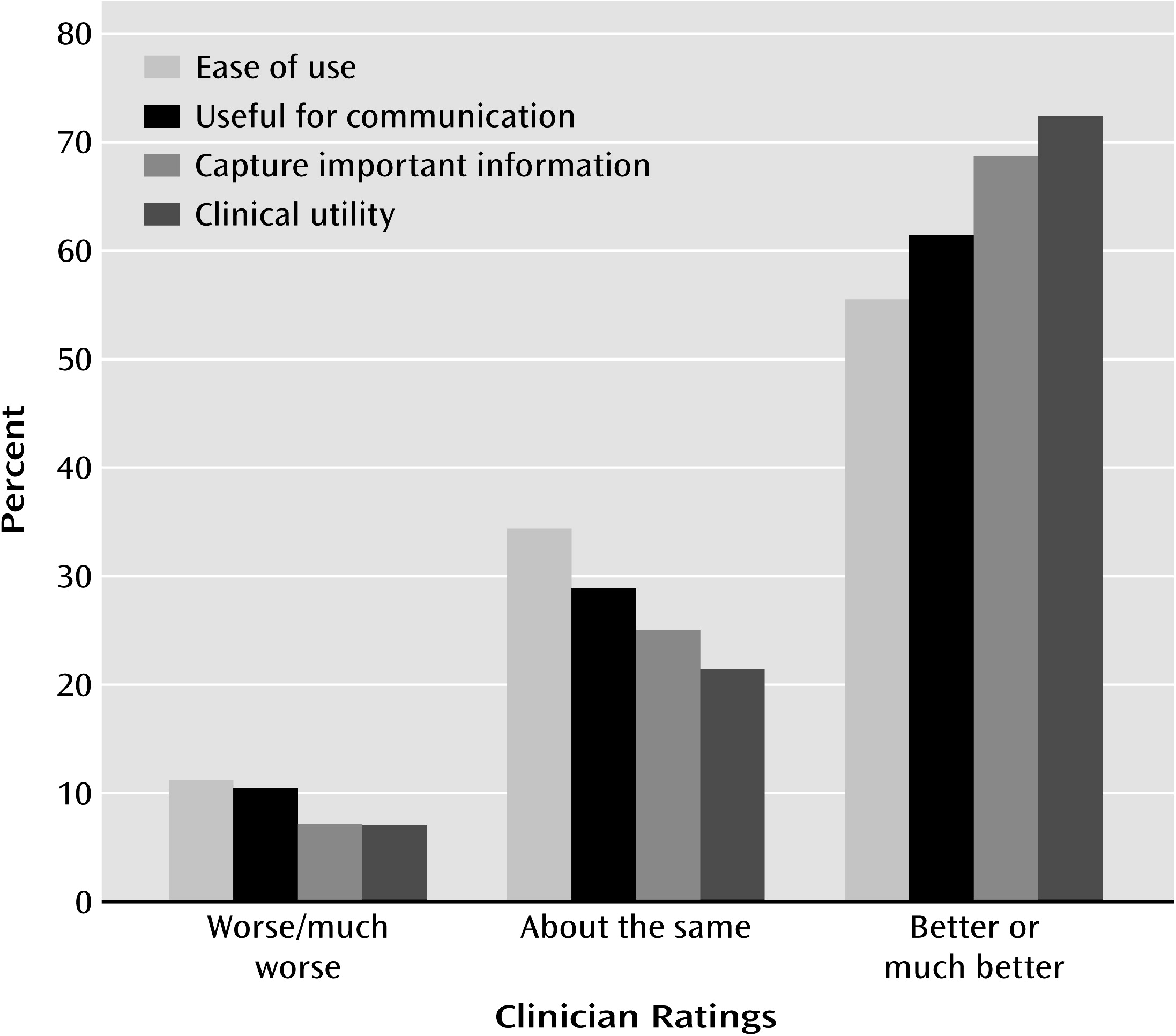

Table 3 shows, rates of comorbidity assessed categorically by using DSM-IV criteria were high and were comparable to rates reported in studies using structured interviews. The median rate of comorbidity among the cluster B disorders was 44.7%. For patients who received a cluster B diagnosis using DSM-IV criteria (50.2% of the patients), the average number of cluster B diagnoses was 1.7 (SD=0.98). The two prototype approaches assigned fewer cluster B diagnoses overall (35.9% and 32.7% of patients, respectively, using the cutoff for clinicians’ ratings of ≥4), and the average patient who received a personality disorder diagnosis received fewer comorbid diagnoses (for the clinician prototypes: mean=1.31, SD=0.67; for the empirical prototypes: mean=1.21, SD=0.41). The number of cluster B diagnoses assigned by using DSM-IV criteria was significantly greater than the number assigned by using the two prototype approaches (clinician prototypes: t=5.23, df=143, p<0.001; empirical prototypes: t=5.84, df=146, p<0.001).

The correlations between dimensional DSM-IV diagnoses made by using the number of symptoms met for each disorder were also high (median r=0.47). The two prototype-matching systems fared better. As

Table 3 shows, for the clinician prototypes, the median correlation between disorders was 0.28; for the empirical prototypes, the median correlation was 0.17. To make a rough estimate of the significance of these differences, we compared the median intercorrelations for DSM-IV dimensional diagnoses with the median intercorrelations for each prototype approach using Fisher’s z. The differences were significant or near-significant even in two-tailed analyses (clinician prototypes: z=1.87, p=0.06; empirical prototypes: z=2.85, p=0.004).

In light of the reduced comorbidity with the prototype approaches, we correlated prototype diagnoses with DSM-IV dimensional diagnoses (number of symptoms met) to determine if the prototype approaches were in fact diagnosing constructs similar to the constructs assessed using DSM-IV criteria. The coefficients in boldface type in

Table 4 reflect convergence across dimensional diagnostic methods. Both prototype methods clearly converged with DSM-IV dimensional diagnosis, although the empirical prototypes showed slightly greater convergence (median: r=0.76) and discriminant validity (median coefficient off the diagonal: r=0.29, lower than the median correlation of the DSM dimensional diagnoses with each other). Thus, the prototypes provided a reasonable proxy for DSM-IV dimensional diagnoses as widely operationalized (number of symptoms met) but did so with less diagnosis of comorbidity.

External Criteria

Although prototype diagnosis appears advantageous in minimizing comorbidity, an important question is whether using prototype diagnosis leads to offsetting losses in validity (predicting external criteria). Thus, we examined the correlations of the disorders as diagnosed by using the four methods with ratings of adaptive functioning, treatment response, and developmental and family history variables.

Adaptive functioning. We first examined adaptive functioning, including an aggregated measure of global functioning (obtained by standardizing and summing the following five ratings selected a priori: Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF], severity of personality dysfunction, quality of romantic relationships, quality of friendships, and occupational functioning) and three relatively noninferential measures (history of suicide attempts, psychiatric hospitalizations, and arrests).

Table 5 reports the partial correlations between each personality disorder diagnosis (with adjustment for the other three diagnoses within each set) and measures of adaptive functioning, with coefficients in boldface type indicating primary hypothesized relationships. (We covaried for other cluster B diagnoses to provide a more accurate portrait of associations with particular personality disorders, although the raw correlations produced generally similar patterns.) The correlations were similar across the four approaches, although they were somewhat larger where predicted for the empirical prototypes.

If a personality axis is to be useful, it must predict variance in adaptive functioning beyond axis I diagnosis. Thus, in a second set of analyses, we used hierarchical linear regression to determine whether 1) any of the four diagnostic methods predicted variance in global adaptive functioning after adjustment for the most prevalent axis I diagnoses in the sample (prevalence ≥10%); 2) the four systems differed in the amount of variance accounted for, and 3) addition of a personality health prototype (i.e., a measure of personality strengths and adaptive resources) to axis II accounted for additional variance after holding constant both axis I and axis II diagnoses.

We performed four regression analyses (one for each diagnostic method) using our aggregated measure of global functioning as the criterion variable. (Data using GAF scores alone produced similar findings.) In step 1 we entered axis I diagnoses; in step 2, axis II (cluster B) diagnoses; and in step 3, personality health prototype ratings. As

Table 6 shows, axis I diagnoses routinely accounted for about 10% of the variance in adaptive functioning, which is substantial. However, in all four analyses, adding the four cluster B diagnoses in step 2 yielded a significant improvement in the model, with multiple Rs increasing incrementally from categorical DSM diagnosis to dimensional DSM diagnosis to clinician prototypes to empirical prototypes. Adding the personality health prototype in step 3 led to large and statistically significant increments in prediction in all four analyses.

Treatment response. Because 95.5% of patients in the study received psychotherapy and 67.7% were treated with antidepressant medication (87.2% of those who received antidepressants received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), we were able to conduct analyses using treatment response as a criterion variable. We consider these analyses to be preliminary, both because of the preliminary nature of the measures and because of the dearth of prior research to inform our hypotheses (that borderline and antisocial features would negatively predict outcome for both psychotherapy and medication). Nevertheless, treatment response is a key variable in validating a diagnostic system (

2), and diagnoses, to be clinically useful, should inform treatment decisions. Once again we report partial correlations, with adjustment for other three diagnoses in each set.

As

Table 5 shows, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, or both were negatively correlated with response to psychotherapy across all four diagnostic approaches. (We did not address differences among therapeutic orientations, given the limited numbers of patients treated by therapists with each orientation.) Once again, the four approaches produced similar coefficients, although DSM categorical diagnoses tended to be least predictive of response to both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy (which is not surprising, given the psychometric disadvantages of dichotomous variables), whereas the borderline personality disorder empirical prototype had the largest (negative) correlations with both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy response.

Etiology. We next compared the four diagnostic methods on associations with the following variables shown in prior research to be relevant to the etiology of cluster B disorders, particularly antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder: physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family history of internalizing disorders (mood and anxiety), externalizing disorders (criminality, alcohol abuse, and illicit drug abuse), and suicide. (Little information in this area is available for narcissistic personality disorder and histrionic personality disorder.)

Table 7 reports partial correlations between each diagnosis and these etiological variables, with predicted correlations presented in boldface type. Once again the results were similar across diagnostic approaches.

Ruling out a rival hypothesis. The data suggest that prototype diagnosis in everyday practice minimizes findings of comorbidity with no offsetting cost in validity. One might argue, however, that the prototype approaches tested here have the advantage of richer item sets (i.e., more information than the eight or nine criteria per disorder in DSM-IV). The ability to include 18 to 20 criteria per disorder is in fact an advantage of prototype diagnosis, because inclusion of that many criteria per disorder would render the count/cutoff approach unusable, as determination of presence/absence would be required for each of 200 criteria across disorders. Nevertheless, we tested this rival hypothesis by examining clinicians’ personality disorder construct ratings—5-point prototype ratings of single-sentence summaries of each cluster B disorder from DSM-IV that convey less information than the diagnostic criteria for each disorder. The data were strikingly similar to those we obtained with the clinical and empirical prototypes: the rate of comorbidity was substantially lower than with the DSM-IV dimensional diagnoses (median r=0.24), and the pattern of external correlates was equivalent.