Clinical Context

A series of converging factors are leading to increased interest in integrated care. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, attention is being focused on improving health outcomes and containing costs. The impact of mental and substance use disorders—hereafter referred to as behavioral health—on reaching these goals is being appreciated in new ways. Across the range of healthcare settings, opportunities to implement outcome-changing interventions are underway and being tested.

One in five U.S. citizens has a diagnosable mental disorder (

1), with only 40% receiving

any treatment for their condition. Of those who do receive care, only half of them see a behavioral health specialist (

2), with the majority being treated in physical health settings by primary and specialty medical care clinicians or alternative medicine settings or social service agencies. In the primary and specialty medical care outpatient setting, patients with behavioral disorders are often not recognized or engaged in effectively delivered treatment, resulting in a mere 13% of patients receiving minimally effective treatment (

3). In the inpatient medical setting, payment shortfalls and challenges in billing for psychiatric care make it difficult to access behavioral health services either in emergency rooms or on general medical and surgical units. The impact of untreated mental illness on total healthcare costs is significant (

4) and can lead to decreased adherence to recommended medical/surgical treatments and lack of follow-up for care. These poor outcomes, coupled with the increase cost in overall health care associated with untreated behavioral illness, have led to the need for better treatment options in primary care and other medical settings. In addition, the lack of a sufficient number of psychiatrists to meet treatment demands necessitates developing models that leverage these limited resources more effectively.

Patients with serious mental illness have a life span shortened by as much as 25 years (

5), with 60% of this attributable to untreated chronic medical conditions, leading to increased cardiovascular morbidity in particular (

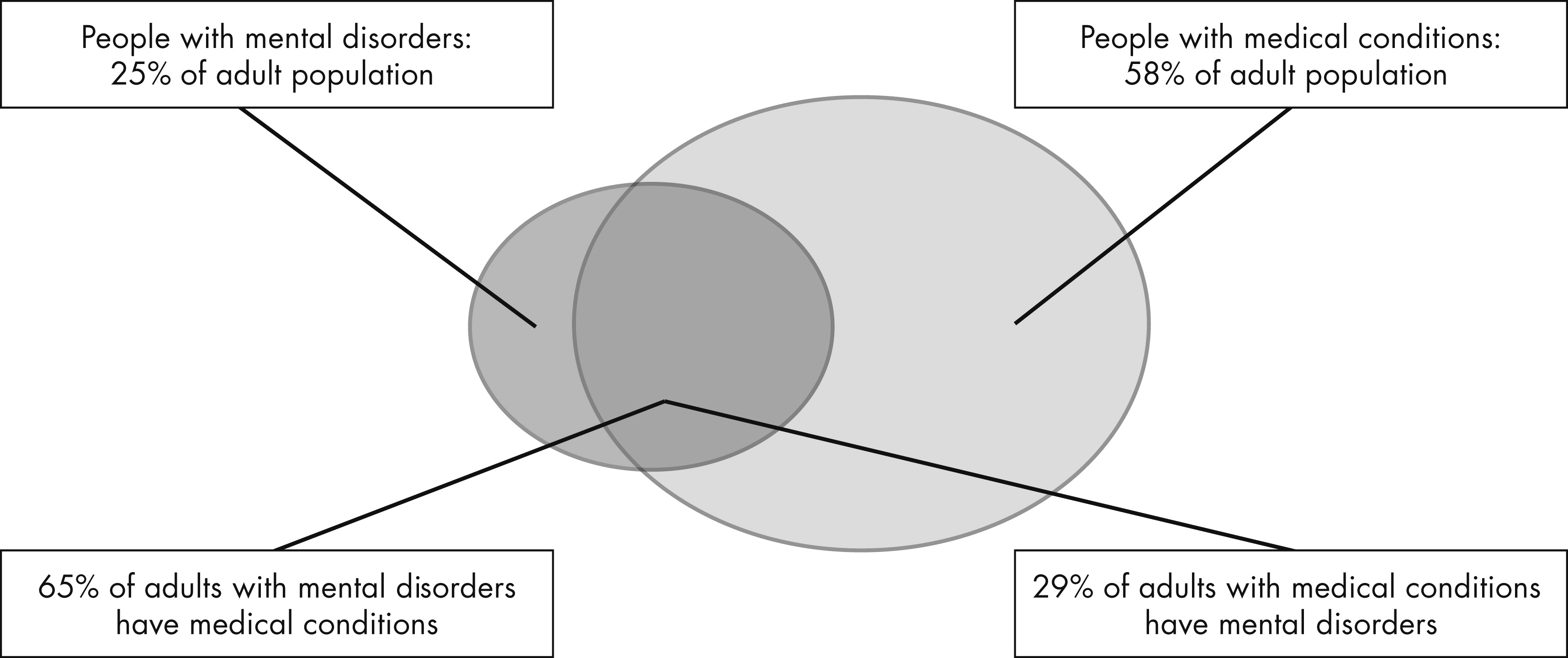

6). As seen in

Figure 1, there is a high rate of physical illness in patients with behavioral illnesses (

7). Further, the second-generation antipsychotics have a well-known contribution to increased cardiovascular risk (

8). A number of other factors also contribute to this mortality, including failure to recognize medical and psychiatric disorders, lack of access to care, poorer quality of care, and inability to afford medical care. A look at baseline data prior to initiating the CATIE study showed a high prevalence of “current” untreated illness, including 30% of patients with diabetes, 66% with hypertension, and 88% with hyperlipidemia (

9) with these disorders not receiving care.

In addition, high utilizers of health care resources, i.e., the 5%−10% of patients consuming 50%−70% of the health care dollars, as a group are being targeted for interventions (

10). An estimated 70% of these have comorbid behavioral health problems (

11). These high utilizers can be found in the population of patients with serious mental illness in public behavioral health settings as well as in general primary care, emergency rooms, and inpatient medical settings. They present an opportunity for collaborative medical and behavioral health interventions designed to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

Questions and Controversy

“I’m concerned about liability and don’t want to provide ‘curbside’ consults because I have not personally examined the patients I would be offering consultation for in the primary care setting.”

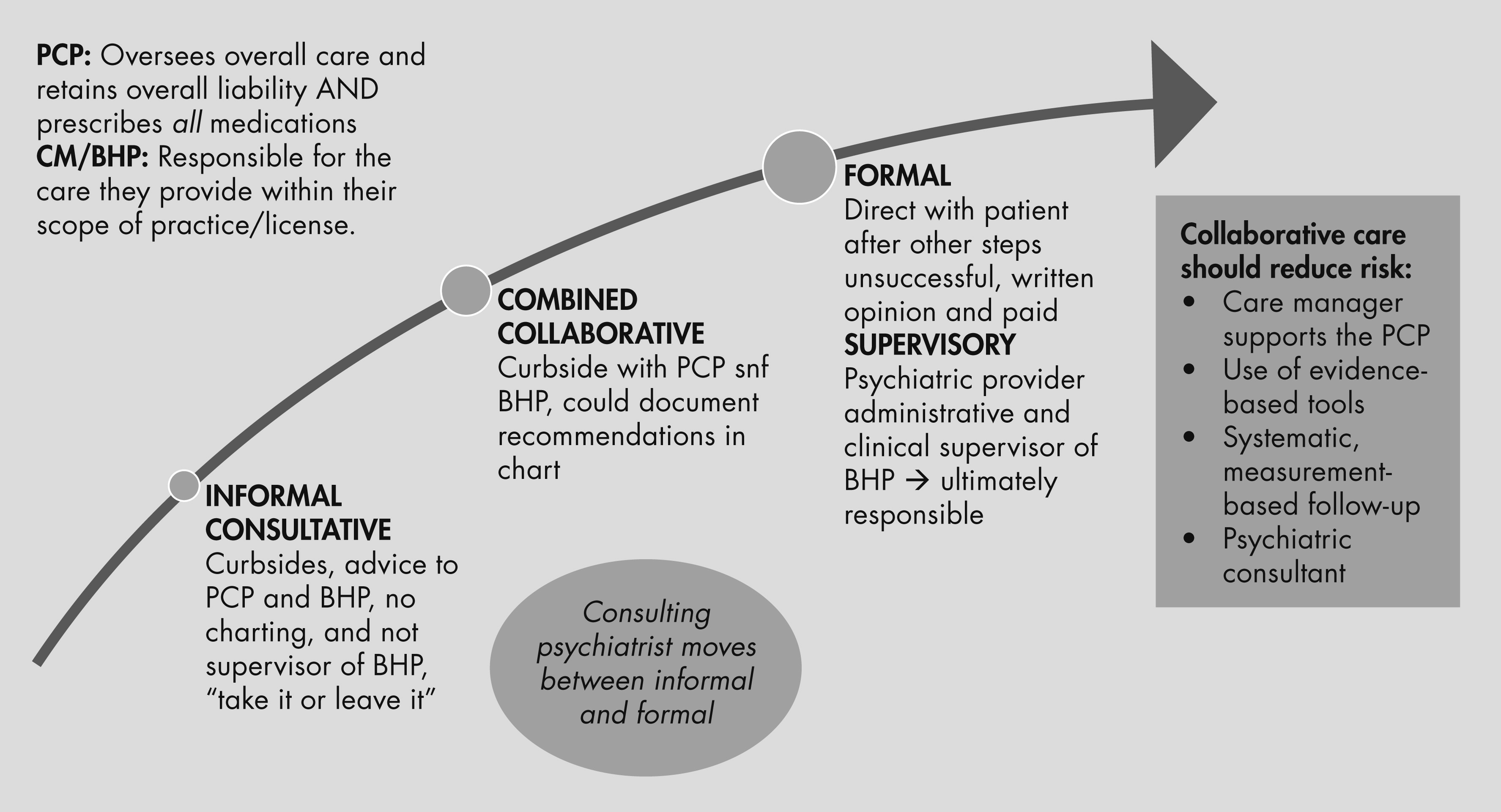

The issue of liability in integrated settings can be considered along two lines. The first is whether or not a doctor-patient relationship was established. Legally, this is usually determined by whether or not there was direct evaluation of a patient (in person or by televideo) and subsequent documentation of findings. Indirect or “curbside” consultations do not establish a doctor-patient relationship so there is presumed minimal liability (

36). An additional area of consultation in collaborative settings in primary care is between the consulting psychiatrist and the behavioral health provider. Liability in this situation can depend on the role of the psychiatrist, which can range from consultative to collaborative to supervisory (

37). There is increased liability if you are the supervisor of the behavioral health provider and are ultimately responsible for the care they provide. Finally, the primary care provider should remain in charge of the overall care provided, deciding if they wish to implement the consultant psychiatrist’s recommendations and prescribe all medications suggested.

Figure 4 shows the nature of the liability and methods to reduce risk.