Introduction

Delirium is a cognitive disorder characterized by acute onset, fluctuating course, altered level of consciousness, inattention, disorientation, memory impairment, disorganized thinking, and perceptual and motor disturbances (

American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It occurs in hyperactive, hypoactive or mixed forms in up to 42% of older hospital inpatients (

Siddiqi et al., 2006) and 70% of long-term care (LTC) residents (

McCusker et al., 2011). In both settings, delirium is independently associated with poor outcomes (

Siddiqi et al., 2006,

Witlox et al., 2010,

McCusker et al., 2010)

The diagnosis of delirium requires the coexistence of symptoms from multiple domains. It is common, however, for older people in different healthcare settings to display one or more symptoms of delirium without having the full syndrome (

Rockwood, 1993,

Kiely et al., 2003). This condition is known as subsyndromal delirium (SSD).

Subsyndromal delirium was described as early as 1517 by Guainerio (

Diethelm, 1971). “Discussing delirium … he emphasized that a predelirious period … can be recognized which … may not lead to full delirium.” Almost five hundred years later,

Lipowski (1990) described a “prodromal phase … in which patients had one or more symptoms of delirium (decreased concentration and ability to think, restlessness, anxiety, irritability, drowsiness, hypersensitivity to stimuli, nightmares) that never progressed to full DSM-defined delirium.” DSM-IV-TR recognizes “sub-syndromal presentations … with some but not all of the symptoms of delirium” and recommends that such presentations be coded as cognitive disorder not otherwise specified (

American Psychiatric Association, 2000). More recently, the DSM-V Neurocognitive Disorders Workgroup has been discussing whether to add subsyndromal delirium as a subcategory of delirium in parallel with a new category, mild neurocognitive disorder (

Jeste, 2010). Of note, neither DSM-IV-TR nor the DSM-V Workgroup distinguishes between subsyndromal presentations that do or do not progress to full delirium.

Because the frequency and significance of SSD in older people is unclear, the primary objective of this study was to determine the frequency, risk factors, course and outcomes of this condition. For the purpose of this review, SSD was defined as the presence of one or more symptoms of delirium, not meeting criteria for delirium and not progressing to delirium (

Levkoff et al., 1996). The review process, modified from the one described by

Oxman et al. (1994), involved systematic selection of articles, abstraction of data, assessment of study validity, and qualitative and quantitative synthesis of results.

Methods

Selection of Articles

The selection process involved four steps. First, three computer databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO) and the Web of Science were searched for potentially relevant articles published from 1996 to June 2011 using the keywords “subsyndromal” or “subclinical” or “subthreshold” and “delirium”. Second, relevant articles (based on the title and abstract) were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Third, the bibliographies of relevant articles were searched for additional references. Finally, all relevant articles were screened to meet the following six inclusion criteria: (1) original research published in English or French; (2) study population of 20 patients or more; (3) patients’ mean age 60 years or more; (4) used acceptable diagnostic criteria for SSD; (5) subjects with SSD were re-screened to exclude those progressing to delirium; and (6) yielded information about one or more of the topics of interest: prevalence, incidence, risk factors, course or outcomes of SSD. There were no attempts to acquire unpublished data.

Abstraction of Data

Information about the study site, study design, population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size at baseline, age, gender, proportion with dementia, diagnostic criteria, period of observation, frequency of observation, type of statistical analysis and the topics of interest was systematically abstracted from each report.

Because subsyndromal symptoms not progressing to delirium may represent the end of a resolving episode of delirium, we recorded whether enrolled cases of SSD were prevalent or incident cases. Prevalent SSD was defined as a diagnosis of SSD at the time of a first assessment; incident SSD was defined as a diagnosis of SSD following one or more assessments with no symptoms of delirium.

Assessment of Validity

To determine validity, the methods of each study were assessed according to relevant sets of validity criteria. Each study was scored with respect to meeting (+) or not meeting (−) each of the criteria.

Data Synthesis

Qualitative

All abstracted information was tabulated. A qualitative meta-analysis was conducted by summarizing, comparing and contrasting abstracted data.

Quantitative

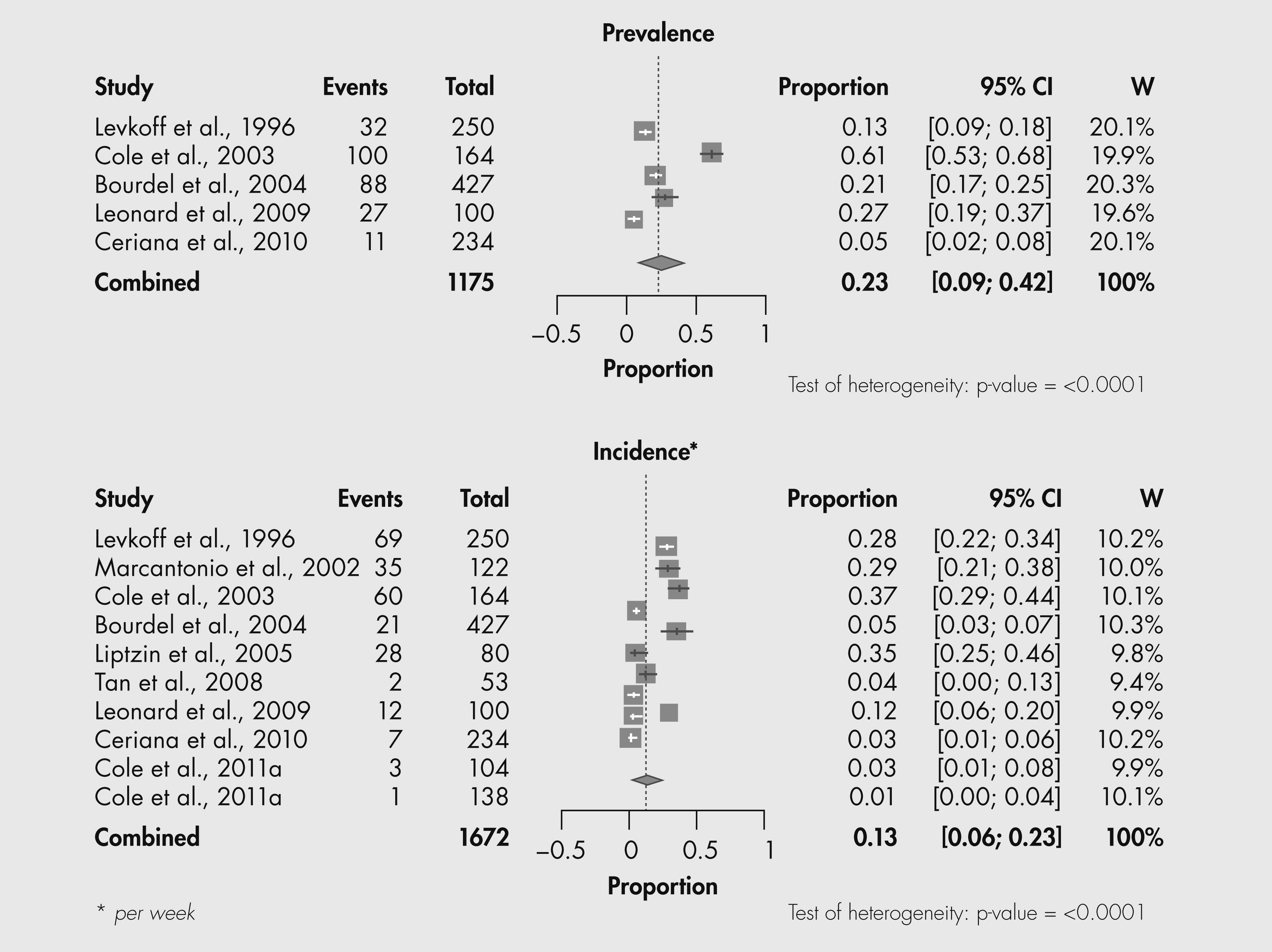

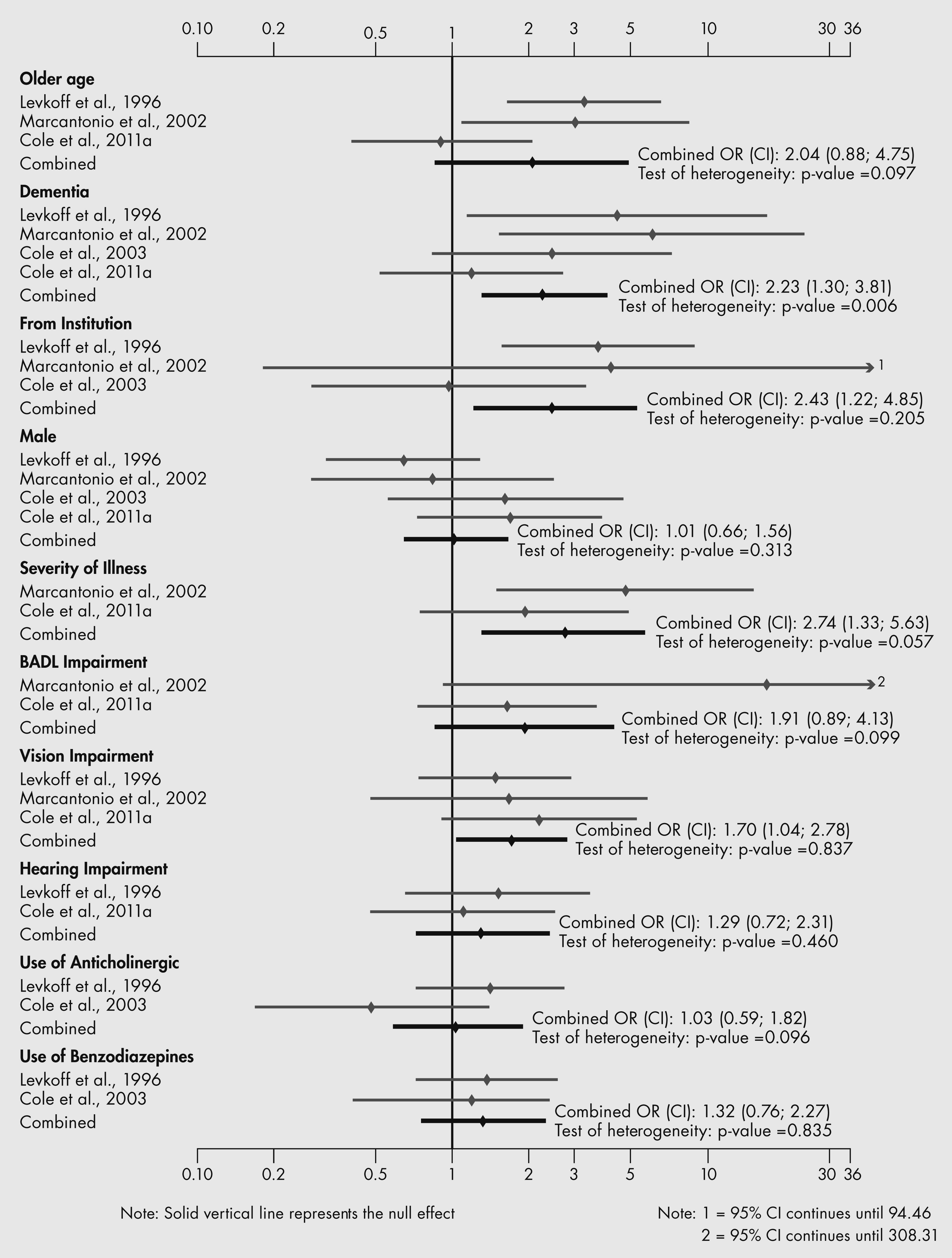

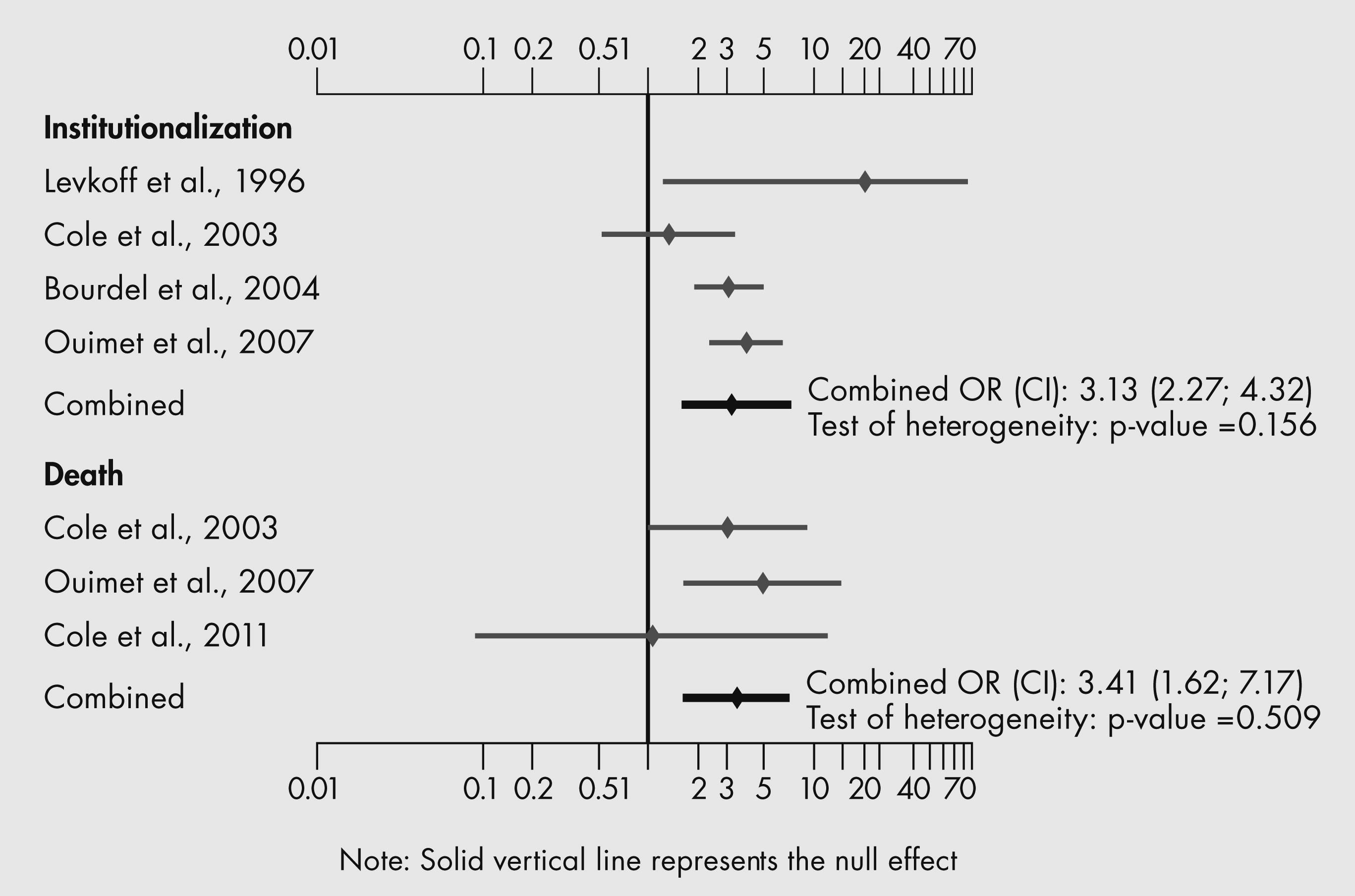

Standard meta-analysis techniques (

Egger et al., 2001) were applied to different groups of studies and studies with usable data from two or more studies. Meta-analysis was used to calculate the combined estimate for three different objectives: (1) prevalence and incidence of SSD (proportion); (2) odds ratio (OR) of SSD associated with each risk factor; and (3) OR of SSD associated with each outcome. For all three meta-analyses, according to usual practice, we used a fixed effect model first, followed by a test of homogeneity. Depending on whether homogeneity was accepted or rejected, we used the fixed or the random effect model to compute the estimate (proportion or OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). The meta-analysis was conducted using the R software 2.13.0 (package: META (metaprop)) and STATA software 10.0 (package meta). Forest plots were drawn of individual and pooled estimates of prevalence and incidence, and ORs for risk factors and outcomes. Finally, when possible, we fitted meta-regression models to assess the impact of study variables on the results (

Egger et al., 2001).

Discussion

Subsyndromal delirium was defined as the presence of one or more symptoms of delirium, not meeting criteria for delirium and not progressing to delirium. We located 12 studies that yielded information about the frequency, risk factors, course and outcomes of SSD in older people. Of note, there was significant unexplained heterogeneity in the results of studies of prevalence, incidence and some risk factors; consequently, the results of this review must be interpreted cautiously.

Subsyndromal delirium appears to be frequent in older populations. The combined prevalence was 23% (95% CI, 9–42%); the combined incidence was 13% (95% CI, 6–23%). Fewer numbers of symptoms required for diagnosis and higher frequency of observation (i.e., more often than weekly) may be related to higher incidence.

Risk factors for SSD appear to include older age, dementia, more cognitive and basic activities of daily living impairment, admitted from an institution, increasing severity of medical illness, vision impairment and more comorbidity. These risk factors are similar to the risk factors that predict the onset of DSM-defined delirium (

Elie et al., 1998); moreover, the frequencies of these risk factors were often intermediate between those of risk factors in populations with and without delirium (

Levkoff et al., 1996,

Cole et al., 2003).

Episodes of SSD appeared to lasted up to 133 days and most ended in recovery. Use of a more restrictive definition of SSD resulted in a more protracted course (

Cole et al., 2012). There are, however, only two studies of course, and these studies are not comparable because of substantial differences in study populations and methodology.

Finally, the outcomes of SSD (i.e., cognitive decline, functional decline, increased length of hospital stay, and increased rates of admission to LTC institutions and death) were poor. These outcomes were often intermediate between the outcomes of older people with and without delirium (

Levkoff et al., 1996,

Cole et al., 2003).

Of note, five studies that did not re-screen enrolled subjects to exclude those progressing to full delirium were excluded from this review (

Kiely et al., 2003,

Marcantonio et al., 2005,

Dosa et al., 2007,

Voyer et al., 2009,

von Gunten and Mosimann, 2010). These five studies reported prevalence rates of subsyndromal symptoms ranging from 11.9% to 51%; the median rate was 39.5%, much higher than the combined prevalence rate of SSD (i.e., 23%) reported in this paper. Two of these studies (

Kiely et al., 2003,

Marcantonio et al., 2005) reported risk factors similar to those in this review, and one (

Marcantonio et al., 2005) reported outcomes similar to those in this review. Thus, the inclusion of subjects with subsyndromal symptoms that may progress to full delirium appears to increase prevalence substantially but may not change risk factors or outcomes.

The above findings may support the notion of a continuum of acute neurocognitive disorder in older people. Within this continuum, the available evidence suggests that increasing number and severity of risk factors for delirium and increasing number and duration of symptoms may predict increasingly adverse outcomes. SSD may represent a point on this continuum, intermediate between no symptoms and full delirium. As such, SSD may be a marker of underlying medical conditions (e.g., infection and drug toxicity) not severe enough to cause full delirium. This hypothesis may be testable by comparing repeated measures of medical and physiological variables at the beginning and end of episodes of SSD and full delirium, respectively.

The above findings may have implications for clinical practice. Because the outcomes of SSD appear to be poor, the presence of even one or two symptoms of delirium may identify older people who warrant clinical attention. Efforts to prevent or detect and treat SSD may be justified. As to prevention, programs that have proved effective in preventing delirium (

Inouye et al., 1999) may be adapted to prevent SSD. As to detection and treatment, interventions may lead to recovery from SSD and improved outcomes. Indeed, one study reports that hospital inpatients who recovered from SSD by 8 weeks had better outcomes than those who did not recover (

Cole et al., 2008).

The above findings may have implications for clinical research. The prevalence and incidence of SSD should be determined using different diagnostic thresholds that include both the number and severity of symptoms. The putative causes (precipitating factors) of SSD should be determined to inform efforts to develop interventions to prevent, or detect and treat SSD. Management of SSD should be recorded in detail and related to rates of recovery and outcomes. Those with SSD should be followed and re-assessed frequently to determine the evolution of this condition. Rates of recovery from SSD should be determined. It will be important to examine if SSD is associated with behavior problems, increased burden on nursing staff and increased costs of care. Because the diagnosis of SSD may result from a relatively small number of observations of fluctuating symptoms of full delirium (

Blazer and van Nieuwenhuizen, 2012), more frequent observations (e.g., every second day) or use of additional sources of information such as daily nurse-observed symptoms of delirium (

McCusker et al., 2010)) may result in detection of more symptoms and a diagnosis of full delirium; furthermore, future studies must try to account for the fact that many subjects may be receiving medical interventions that probably prevent the emergence of full delirium. Finally, even though SSD is probably a delirium spectrum disorder rather than a distinct entity, further research is necessary to clarify the relationship between SSD and full delirium.

This systematic review has six strengths. Only studies that re-screened cases to exclude those progressing to delirium were included. The validity of included studies was systematically assessed. There was a qualitative and quantitative synthesis of results. When possible, meta-regression analysis was used to examine study variables to account for variability in study results. Nine of the studies enrolled subjects with incident SSD and provide particularly strong evidence of risk factors and outcomes. The results of studies of prevalent SSD were presented separately and, for the most part, supported the findings of studies of incident SSD.

This systematic review has four potential limitations. The literature search was conducted by one author only and limited to articles published in English and French because there were no resources to translate articles written in other languages. The data were abstracted by one author only. Finally, there was significant unexplained heterogeneity in the results of studies of prevalence, incidence and some risk factors; it is arguable that such heterogeneity should have precluded the combining of the results of the different studies.