Qualitative Analysis

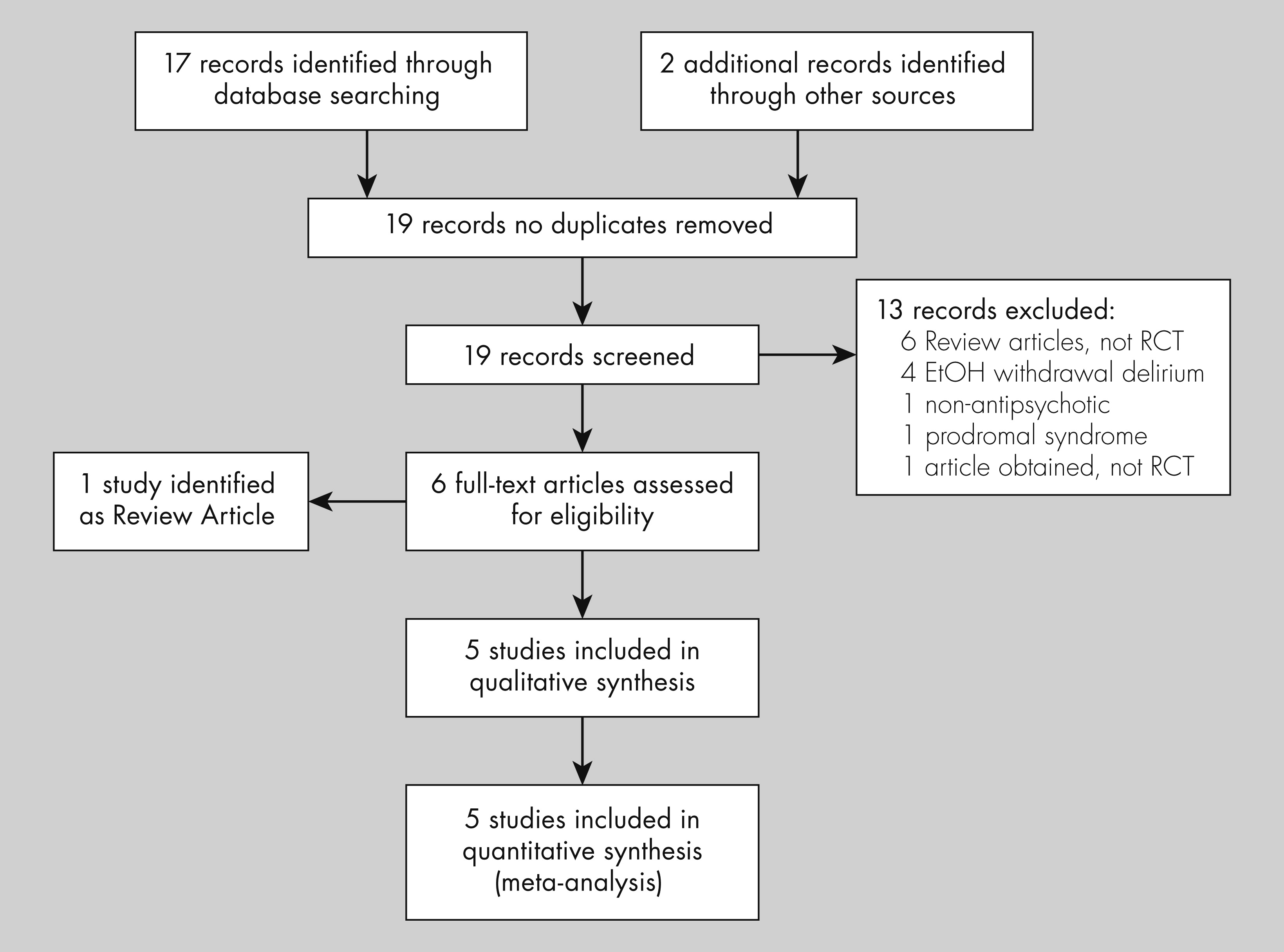

The initial search identified 126 citations from MEDLINE, 281 from PsychINFO database, and 17 from the Cochrane Controlled Trials database. One additional citation was identified after review of secondary references. After a review of the abstracts, 19 articles were identified as potential candidates and reviewed in detail. Of those, five studies met inclusion criteria (exclusion rationale are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram, see

Figure 1),

22–26 and were included for review (see

Table 1 for a summary of the included studies). All included studies were randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trials spanning five different countries: Japan,

24 The Netherland,

25 Thailand,

23 China,

26 and the USA.

22 All five studies examined elderly patients undergoing surgery. Study medications included haloperidol,

24–26 risperidone,

23 and olanzapine,

22 and the prevention of postoperative delirium was the primary outcome. The methodological quality of each study was evaluated using Cochrane criteria,

29 and a summary of this evaluation is presented in

Table 2.

Prakanrattana and Prapaitrakool

23 included 126 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery in their study, with 63 participants in each arm. Patients were randomly assigned to receive risperidone lmg orally or placebo immediately after surgery by staff not directly involved in patient care. Among 126 randomized patients, the occurrence of postoperative delirium in the risperidone group was significantly less common than in the placebo group (11.1% vs. 31.7%, respectively,

p = 0.01, (RR [95% CI]: 0.35 [0.16–0.77]). Other postoperative outcomes such as presence of postoperative complications and the length of hospital or ICU stay were not statistically different between the groups. The number need to treat (NNT) in this study was 4.85.

In a study evaluating the use of olanzapine, Larsen et al.

22 included 400 patients undergoing simple or complex hip or knee surgery in a randomized, double-blind placebo trial: 196 patients received olanzapine 5 mg orally immediately pre- and postoperatively (a total of 10 mg of olanzapine) and 204 patients received placebo. Delirium was identified using DSM-III-R criteria in conjunction with the MMSE, the DRS-R-98 and the CAM. Compared with the placebo group, the incidence of postoperative delirium was lower in the olanzapine group (14.3% vs. 40.2%; 95% CI 17.6–34.2,

p < 0.0001). Despite this lower incidence, among those who developed delirium, the duration of delirium was longer in the olanzapine group compared with the placebo group (2.2 days vs. 1.6 days [SD 0.7] days;

p = 0.02). Moreover, delirium was more severe in the olanzapine group compared with the placebo group (mean DRS total scores were 16.44 in the olanzapine group compared with 14.5 in the placebo group,

p = 0.02). The calculated NNT in this study was 4.

Kalisvaart et al.

25 included 430 patients admitted for acute or elective hip surgery in their study with patients randomized to a prophylaxis group haloperidol 0.5 mg po three times daily, for a total of 1.5 mg po daily. The study drug was administered from the initial day of their hospital admission and continued through the postoperative day 3 (for a maximum of 6 days). All of the clinical staff in contact with study participants were blinded to the treatment conditions, as were the participants of the study. Of the 382 patients who completed the protocol, 55 patients (15.8%) developed delirium diagnosed using DSM-IV and CAM criteria. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate differences between the groups for the presence of postoperative delirium, Student’s

t-tests were used to evaluate parametric variables, and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to evaluate nonparametric variables. There was no significant difference between the prophylaxis and the placebo group in the incidence of postsurgical delirium. There were, however, differences in the secondary outcomes of severity and duration: participants in the prophylaxis arm scored lower on the DRS-R-98 delirium severity scale (14.4 ± 3.4 vs. 18.4 ± 4.3, with a mean difference of 4.0, 95% CI 5 2.0–5.8;

p < 0.001), had a lower duration of delirium (5.4 vs. 11.8 days, with a mean difference of 6.4 days, 95% CI 4.0–8.0;

p < 0.001) and had shorter hospital stays (17.1 vs. 22.6 days, with a mean difference of 5.5 days, 95% CI 1.4–2.3;

p < 0.001). There were no noted drug related side effects.

In another study evaluating the use of haloperidol, Kaneko et al.

24 included 78 patients undergoing elective gastrointestinal surgery. Patients were randomly allocated to two groups; 38 patients received prophylaxis with 5 mg intravenous haloperidol on postoperative days 1 through 5, and 40 patients received normal saline under the same conditions. The authors report that patients were randomly selected using a “closed envelope system,” but the specifics of the blinding procedures were not clarified. DSM-III-R criteria were used to diagnose postoperative delirium, which developed in 17 of 78 patients (21.8%). However, only 4 (10.5%) patients developed delirium in the study group compared with 13 (32.5%) in the placebo group (χ

2 not reported, but the authors report a

p value of <0.05). The intensity and duration of the delirium were noted to be worse in the control group. There were no complications or adverse outcomes noted with haloperidol treatment except that 1 patient developed transient tachycardia. The calculated NNT in this study was 4.55.

Wang et al.

26 also investigated the use of haloperidol to prevent delirium among patients after non-cardiac surgery. Their study enrolled 457 patients above the age of 65 years who were admitted to the intensive care unit after non-cardiac surgery: 229 patients were randomized to receive 0.5 mg IV bolus of haloperidol followed by continuous infusion at a rate to 0.1 mg/h for 12 hours (for a total dose of 1.7 mg of haloperidol IV) postoperatively vs. 228 patient who received normal saline placebo. The study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled two-center study. The study drug was identical in appearance to placebo and was mixed by a nurse not involved in other aspects of the study. Nonpharmacologic environmental approaches to reduce incidence of delirium were implemented for all patients irrespective of study arm. The primary outcome measured was incidence of delirium during first 7 postoperative days as measured by the CAM-ICU. Secondary outcomes included time to extubation, length of stay in ICU and hospital, as well as all-cause mortality in the first 28 postoperative days. Assessments were performed daily by research team members not involved in the care of the patients using the CAM-ICU and the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale. The study was an intention-to-treat analyses and

t-tests were used to evaluate parametric variables, and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to evaluate nonparametric variables. The incidence of delirium in the haloperidol study arm was significantly lower with 35 out of 229 subjects (15.3%) of participants developing delirium in the treatment arm compared with 53 out of 228 subjects (23.2%) of participants in the control arm. After adjusting for the differences between the two groups, the odds ratio of delirium in the haloperidol vs. placebo group was 0.57 (95% CI 0.35–0.94,

p = 0.03). The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter (21.3 vs. 23 hours), but the length of hospitalization did not significantly differ between the two groups. Importantly, no adverse events were identified, no EPS occurred, and changes in QTc prolongation were similar in both arms. The NNT in this study was 12.

Quantitative Analysis

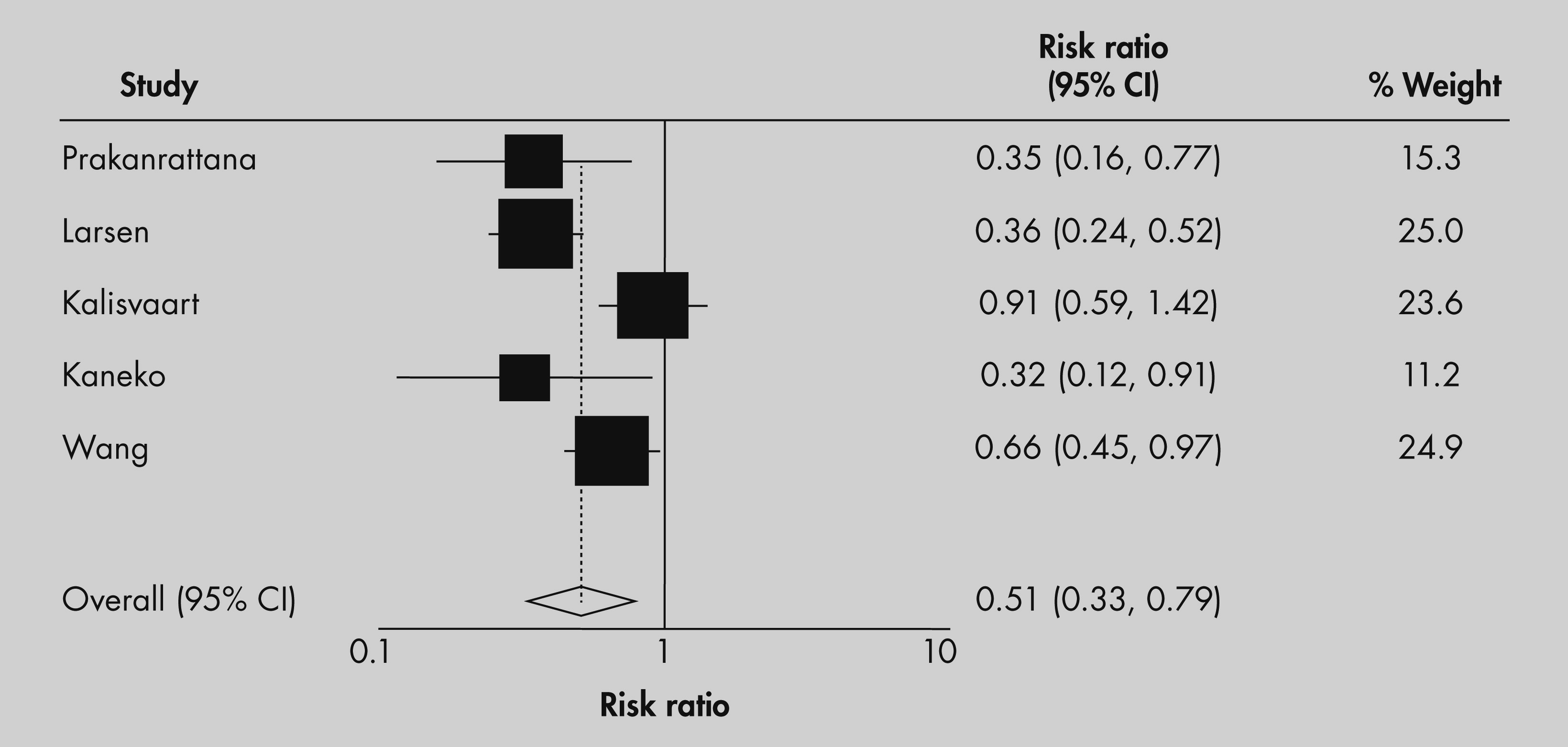

A Forest plot with corresponding relative risk ratios, confidence intervals, and weighting coefficients are presented in

Figure 2. Four of five studies showed a significant decrease in incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients receiving antipsychotic medication prior to or immediately after surgery. The pooled relative risk of the five studies resulted in a 50% reduction in the relative risk of the incidence of delirium among those receiving antipsychotic medication compared with placebo (RR [95% CI]: 0.51 [0.33–0.79]). All but one study

25 concluded that if delirium in prophylaxis group develops, it is milder with a shorter duration. No study reported any serious or statistically significant adverse outcome, including adverse cardiac outcomes.

There was significant heterogeneity associated with the five studies analyzed in this meta-analysis (Q statistic = 13.33 [

p < 0.01]; I

2 = 0.15). In order to account for random factors across studies that cannot be adequately modeled, we used a random effects model. Additionally our meta-analysis sought to evaluate different possible variables across studies that may have contributed to heterogeneity. Because the quality of the Kaneko

24 study was limited, we repeated the analysis excluding this study from the analysis. When the Kaneko study was excluded from the meta-analysis, heterogeneity remained statistically significant (Q statistic = 12.33 [

p < 0.01]; I

2 = 0.17). Exclusion of the study did not significantly alter the results of the meta-analysis (RR [95% CI]: 0.54, [0.34–0.87]). Next we evaluated the Kalisvaart study as the overall incidence of delirium in this study was lower than that found in the other studies and lower than the incidence rate the authors assumed in their power analysis (15.8% vs. 40%). As a result, this study may have been underpowered to detect a difference. When the Kalisvaart

25 study was excluded from the meta-analysis, heterogeneity was no longer statistically significant (Q statistic = 5.97,

p = 0.13). Exclusion of the study did not alter the results of the meta-analysis (RR [95% CI]: 0.49, [0.29–0.65]).

Examination of the funnel plot did not indicate publication bias. However, it is important to note that the overall number of studies in this analysis was small, which may limit inferences that can be made about the symmetry of the plot.