Background

The prevalence of insomnia in primary care patients is as high as 69% [

1,

2] compared to 33% in the general population [

3]. Insomnia can exist as a primary disorder or co-morbid with other conditions including depression [

4] and chronic pain. In the past insomnia was considered to be a symptom of these conditions with the assumption that treatment of these ‘primary’ conditions would lead to the resolution of insomnia, eliminating the need for targeted insomnia treatment. There is now evidence to suggest that insomnia often persists following resolution of these ‘primary’ conditions, and that it generally does not spontaneously resolve over time if left untreated [

5]. Insomnia is independently associated with significant morbidity including fatigue, impaired concentration and memory, irritability, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, decreased quality of life, and increased risk of new-onset psychiatric illness [

1,

6–

9]. In addition, there is evidence that insomnia may confer risk for medical illness including hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes [

10,

11], and is associated with increased overall health care costs [

9].

The most common approach to the management of insomnia is medication treatment. Numerous trials have documented moderate efficacy with benzodiazepine receptor agonists [

12,

13]. The advantages of medications are that they are widely available and, when effective, lead to clinical improvement rapidly. The disadvantages are the potential for side-effects, dependence, and tolerance over time. Perhaps the most important disadvantage is that medications are usually not curative, leading to long-term treatment over many years despite a lack of safety and efficacy data for their long-term use beyond 1–2 years.

An alternative treatment approach is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I is a non-pharmacological approach to treatment comprised of several strategies. The goal of CBT-I is to target those factors that may maintain insomnia over time, such as dysregulation of sleep drive, sleep-related anxiety, and sleep-interfering behaviors. This is accomplished by establishing a learned association between the bed and sleeping through stimulus control, restoring homeostatic regulation of sleep through sleep restriction, and altering anxious sleep-related thoughts through cognitive restructuring. By changing sleep-related behaviors and thoughts, CBT-I may target those factors that cause insomnia to persist over time. CBT-I is delivered over the course of 4–8 sessions that occur weekly or every other week for 30–60 minutes each. There are two main disadvantages to CBT-I. First, during the first few weeks of treatment there is often an acute reduction in total sleep time that can lead to the side effect of increased daytime sleepiness which, for some, is enough to lead them to drop out of treatment. Second, improvements from CBT-I are typically not seen until 3–4 weeks into treatment. While a few research studies have examined the efficacy of nurseled CBT-I in primary care settings [

14], in current clinical practice it is usually necessary to refer out to individuals with specialized training in this treatment. It should be noted that the core therapies for CBT-I substantially differ from other forms of CBT and it is for this reason that the abbreviation CBT-I denotes this form of CBT specifically for insomnia [

15].

Treating insomnia with CBT-I, as opposed to medication, has a number of potential advantages, including fewer known side effects, and an explicit focus on treating the factors that may be responsible for perpetuating chronic insomnia in an effort to produce more durable effects. Some patients also prefer non-medication treatments [

12,

16,

17]. Providers often have negative attitudes towards hypnotics as well, and prefer to reduce their prescriptions of such medications [

18]. These advantages of CBT-I suggest that it might be a viable option for the treatment of insomnia [

12,

17].

Evidence suggests that CBT-I is effective when compared with placebos [

19,

20]. A new systematic review [

21] meta-analyzes evidence from 14 randomized trials comparing groups of patients given CBT-I to control groups. A variety of controls were combined in that analysis, such as patients on a waiting list to receive CBT-I and patients offered a sleep hygiene program which has been shown to be of little or no benefit [

17]. The meta-analysis found that CBT-I had a medium to large effect in reducing insomnia, and that the effects were maintained even after conclusion of the treatment period. But this review does not tell us whether CBT-I is as effective as sleep medications. The AHRQ Evidence-based Practice review [

20] addressed that question, but it was published in 2005 and lacks evidence published since September 2004.

The primary objective of this review is to examine the most up-to-date evidence comparing CBT-I to medications in patients with primary and comorbid insomnia and assess the comparative effectiveness of these treatments.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

We considered only published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with no exclusions based on date of publication or language. Inclusion criteria were defined in advance of data abstraction using the PICO framework below [

22].

Patients

Included studies examined patients aged 18 or older diagnosed with chronic insomnia per DSM-IV criteria. Studies of patients with medical or psychological comorbidities were included but analyzed separately, as were studies of patients already using medications for insomnia. Studies with fewer than 10 patients in each group were excluded.

Intervention

Study patients had to be treated with either individual or group CBT-I to be included. Therapy had to be delivered by a professional: studies of self-help programs were excluded. Studies with telephone or internet sessions were included if those sessions were supplementary to in-person CBT-I. We did not set minimum or maximum treatment periods for study inclusion. Studies that were designed to compare individual elements of a CBT-I program to each other were excluded.

Comparison

We examined all RCTs comparing CBT-I to FDA approved prescription or non-prescription medications used to treat insomnia both on- and off- label (e.g. benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists, antidepressants, and antihistamines).

Outcomes

Studies had to report at least one quantitative measure of sleep to be included in this analysis. These measures included sleep latency, wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and total wake time. Measures from patients’ sleep diaries and measures from automated means (polysomnography and actigraphy) were analyzed separately because of known unreliability in patients’ perceptions of sleep. As secondary outcomes, standardized measures of quality of life, sleep quality, and psychological outcomes including depression, anxiety, and fatigue were also abstracted when available, as was data on adverse events.

Literature Searches and Study Inclusion/Exclusion

We searched Medline (OVID interface, Additional file 1: Table S1), the Cochrane Central Register (Additional file 1: Table S2), EMBASE (Additional file 1: Table S3), and PsycINFO (Additional file 1: Table S4). Search strategies combined indexing terms for CBT with indexing terms for insomnia, then applied filters for randomized trials. We did not limit the search to specific drugs. Detailed syntax of each search is reported in the supplement. All searches were completed in September 2011. We also reviewed published systematic reviews [

19,

20,

23] for eligible RCTs which may have been missed by our searches: none were found.

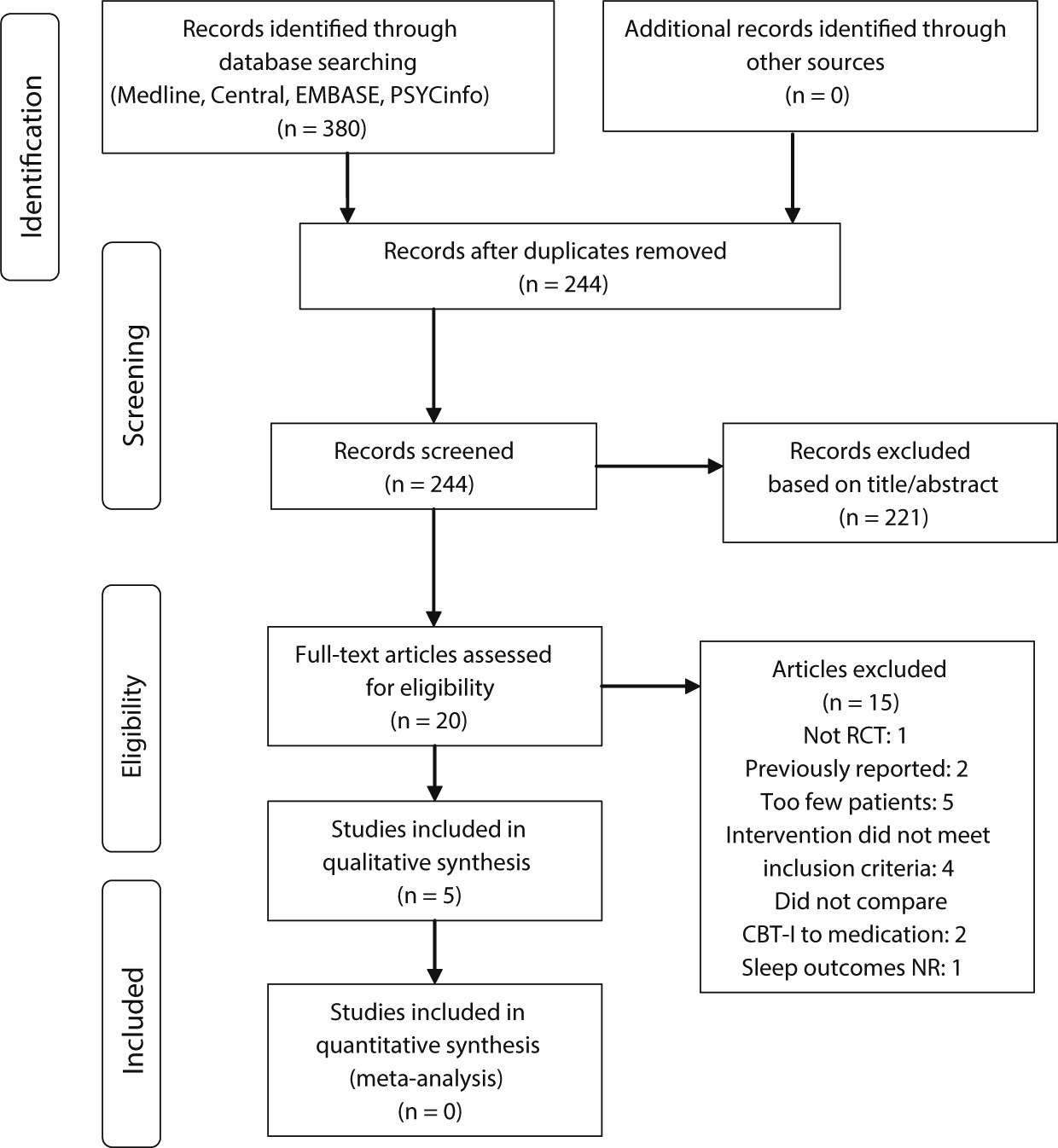

Disposition of the search hits and articles retrieved is shown in

Figure 1. Two research analysts (MDM, BL) reviewed full text of each retrieved article to determine whether it met the stated inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (PG). Reasons for exclusions of studies are summarized in

Figure 1 and the complete list of excluded articles with reasons for exclusion are in Additional file 1: Table S5.

Data Abstraction and Analysis

Study characteristics were abstracted into a database with fields for study setting, patient selection criteria, CBT-I interventions, and reviewers’ comments. This database helped us decide how to organize studies and evidence tables. Study results were then abstracted directly into evidence tables. Data synthesis methods followed the practice of the Cochrane Collaboration. Assessment of RCT quality was done using a nine-point scale (Additional file 1: Table S6) based on scales by Jadad [

24] and Chalmers [

25]. Quality ratings for each individual study are shown in Additional file 1: Table S7. The overall quality of the evidence base for each comparison was rated using the GRADE approach [

26–

28].

Outcome Measures

Key quantitative measures of sleep are sleep latency (the amount of time it takes for a person to fall asleep after retiring to bed), total sleep time (TST), time spent awake after sleep onset, total wake time during the sleep period, and sleep efficiency (the percentage of the sleep period during which the patient is actually asleep). It should be noted that TST is not only an outcome variable, but is manipulated as part of CBT-I via the restriction of time spent in bed. Specifically, sleep restriction therapy requires that time in bed be reduced to a time interval that equals the patient’s ‘sleep ability’ by measuring average TST during a two-week baseline period. The net result of this, after completion of CBT-I, is that many patients do not recover their baseline TST but are nevertheless substantially improved with respect to other aspects of sleep. This said, it is important to assess TST as an outcome measure so that the effects of CBT-I are fully characterized. There can also be substantial differences between automated measures of sleep time and patients’ self-reports on sleep diaries.

Most studies reported these sleep outcomes for multiple time points. Where available, we tabulated results for two of those points from each study: the time period immediately following treatment, which for CBT-I was typically 4 to 8 weeks from the start of therapy, and for the longest follow-up period reported by study authors, which was typically six to twelve months.

As secondary outcomes, we also analyzed results from standardized patient questionnaires on sleep and insomnia symptoms, such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Non-standard instruments, such as asking the patient to grade his or her sleep quality on a scale of 1 to 5, were not analyzed.

Daytime outcomes analyzed included standardized and validated measures of patients’ general quality of life, and measures of psychological outcomes including depression, anxiety, and fatigue.

Results

Our search found a total of five RCTs that met the inclusion criteria and compared CBT-I to medications. The five trials all involved patients with primary insomnia. The trials compared CBT-I to zopiclone [

29], zolpidem [

30], temazepam [

31,

32], and triazolam [

33]. The design and quality of these studies is reported in

Table 1 and their short and long term results are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3 respectively. Only one trial compared CBT-I to drug therapy in patients with comorbid insomnia [

34]: the drug used was nefazodone (now withdrawn from the market), so the study was excluded from further analysis. The evidence base was too small and heterogeneous for meta-analysis.

Quantitative Sleep Outcomes

All trials asked patients to complete sleep diaries. All but one also used polysomnography or actigraphs to objectively measure sleep outcomes. Reported sleep measures included sleep latency, TST, and total time spent awake during the night. Our results tables show the mean changes in these variables from baseline to the end of the active treatment period (

Table 2) and the end of the study follow-up period. Some studies reported intermediate time points as well, which were consistent with the initial and final results.

The evidence comparing benzodiazepines to CBT-I in the short term is of very low grade (

Table 4). One study (meeting 3 of 9 quality points) found the benzodiazepine temazepam to be statistically more effective than CBT-I for improving sleep latency and sleep efficiency, while another (meeting 6 of 9 quality points) found no difference (

Table 2). Conversely, there is moderate grade evidence suggesting CBT-I is superior to the non-benzodiazepines zopiclone and zolpidem for improving sleep measures in the short term.

Long-term studies (6 to 24 months after completion of treatment) consistently favor CBT-I over both benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines for improving sleep efficiency, with moderate grade evidence for the former and low grade evidence for the latter. CBT-I generally led to improvements of 30 to 45 minutes in sleep latency and 30 to 60 minutes in total sleep time (

Table 3). Sleep efficiency improved 8 to 16 percent with CBT-I, but improved less with drugs. The effects of CBT-I appear to be sustained over time, while the effects of drug therapy decline.

Patients’ Subjective Evaluation of Sleep

Only two of the studies reported results from standardized sleep questionnaires given to patients at the end of the follow-up period. Both reported that patients were significantly more satisfied with CBT-I than with zopiclone, but they did so using different measures. In Morin’s study [

31] the Sleep Impairment Index declined 10 points after 24 months for patients treated with CBT-I, but only 4 points for patients given tamezepam (p = 0.01). Wu et al [

32] surveyed patients using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: after 8 months this measure improved an average of 1.2 points in patients treated with CBT-I, while it worsened 0.8 points in patients given tamezepam (p < 0.01).

Quality of Life and Daytime Outcomes

Evidence comparing CBT-I and medications for insomnia-related outcomes other than direct sleep measurements is scarce. One trial [

35] found no significant difference in overall quality of life (SF-36) between patients treated with CBT-I and patients treated with zopiclone. This study also found no difference in daytime fatigue between the two groups, as measured by patients’ reaction times. Quality of life outcomes were not reported in the other trials.

The same trial also measured patients depression and anxiety symptoms using several standard questionnaires. Six months after treatment, scores were significantly improved on both components of the State-Trait Anxiety Index for CBT-I patients compared to zopiclone patients (state: −5.11 vs. +1.61, p < 0.05; trait: −4.47 vs. +1.97, p < 0.01). Trends towards improved results with CBT-I were observed in the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and the Worry Domains Questionnaire, but the differences between groups were not statistically significant. No difference between groups was observed in the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems.

Adverse Effects of Treatment

Reporting of adverse events in all of these trials is limited, so we cannot draw any conclusions regarding the relative safety of CBT-I compared to benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepines.

We found no trials comparing CBT-I to antihistamines or antidepressants.

Discussion

Overall, we found that CBT-I is at least as effective for treating insomnia when compared with sleep medications, and its effects may be more durable than medications. The strength of these claims needs to be tempered with a critical evaluation of the available evidence. There have only been a handful of studies that have included both cognitive behavioral and pharmacotherapy treatment arms for inclusion in this systematic review. A significant limitation of the studies is that they all focused on patients with primary insomnia who, while more straightforward for inclusion in clinical studies, may not be representative of the majority of patients who have comorbid medical or psychiatric disorders. RCTs of CBT-I only, with no medication comparator condition, generally find that treatment is as efficacious in those with comorbid disorders compared to those with primary insomnia (for example see [

38]). While this suggests that the results of this review may also hold for comorbid insomnia, studies including both CBT-I and medication arms are needed in this patient population. The studies also were diverse in terms of sleep-related outcome measures (subjective versus objective) and demographic composition. In terms of outcome measures, insomnia RCTs generally find larger effects of treatment on subjective measures such as questionnaires than on objective measures of actigraphy and polysomnography. However, this does not limit the meaning of the findings since the diagnosis of insomnia relies on patient report and not on a diagnostic laboratory test. In terms of demographic composition, three of the five studies we included were in older adults. Future studies will need to be conducted in both older and younger adult samples, but it is noteworthy that the findings were generally consistent across studies despite the diversity of subject ages.

The results of this analysis indicate that more research is warranted in this area to better understand the relative efficacy of CBT-I and hypnotics in order to make decisions about best practices.

Even with these limitations, these results have a number of important treatment implications for the primary care setting. First, providers should consider CBT-I as a treatment option for their patients with insomnia. Second, CBT-I may have advantages when compared to medications, most notably more durable treatment gains that reduce or eliminate the need for long-term pharmacologic treatment. In addition, those significant clinical gains can be made in a relatively short number of treatment sessions (most studies were 6–8 weekly or bi-weekly sessions). Future research comparing the efficacy of CBT-I and hypnotics may find that treatment efficacy is moderated by patient characteristics such as age or comorbid diagnoses. These data can lead to the development of treatment algorithms that would allow primary care providers to make more informed treatment decisions. Of note, three of the studies [

29,

31,

32] included a treatment arm that was a combination of CBT-I and medication. Outcomes were generally comparable to those receiving CBT-I alone, but future studies should examine additional strategies for combination treatment that capitalize on the relative advantages of medication (rapid onset on therapeutic response) and CBT-I (long-term durability of treatment gains).

Despite the evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT-I, many providers may not be aware of its existence or know how to refer patients for treatment [

39]. Referral can be accomplished in several ways. First, there is a growing registry of providers who have sought specialized certification in the delivery of CBT-I and other behavioral sleep medicine interventions to whom patients can be referred (

http://www.absm.org/BSMSpecialists.aspx). These providers are primarily clinical psychologists and are located in a variety of settings including sleep disorders centers and private practice [

14,

40]. Second, primary care practices can partner with local psychologists or others to provide CBT-I. Lastly, a few studies have yielded promising results by implementing CBT-I in the primary care setting by nurses provided the necessary training and supervision [

41,

42]. By utilizing these various approaches, primary care providers can make CBT-I accessible. Yet, even with these options, getting a patient access to CBT-I may present challenges not encountered when providing a patient with a simple prescription for a sleep medication. First, there can be greater difficulty in getting insurance coverage for CBT-I than for medications. Second, therapists to provide CBT-I may not be available in some parts of the country or the world. However, the evidence reviewed in this manuscript suggests that the additional effort in obtaining access to a therapist if available may be worth the more long-term improvements patients may achieve with CBT-I without the extended use of sleep medications.

The GRADE approach used to grade the evidence base for the comparisons examined in this study can help identify areas where the evidence is least robust and where additional studies can most impact our conclusions about CBT-I. GRADE can also help identify causes for the weakness of the evidence base. Data on long-term outcomes of CBT-I compared to non-benzodiazepines is still sparse, and inconsistencies in the data comparing CBT-I to benzodiazepines in the short term need to be resolved. Data on CBT-I for patients in critical subgroups of interest such as those with comorbid insomnia is sparse as well, and there have been no trials comparing CBT-I to approved drugs in these patients. This is an important limitation of the findings in our review as many patients presenting with insomnia to primary care practices will have secondary or co-morbid insomnia, and thus the findings here may not be as generalizable to those settings. In addition, comparisons of CBT-I to drugs commonly used off-label for the treatment of insomnia, including antidepressants and antihistamines, are not available. Lastly, all studies in this field suffer an unavoidable risk of bias because double-blinding is not possible.