Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Introduction

| Evidence of target validation | |

|---|---|

| Neurotransmitter and neurohormonal dysregulation | |

| Dopamine9,10 | Antipsychotic agents block dopamine D2 receptors and are potent antimanics |

| Serotonin11 | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors of uncertain efficacy, atypical antipsychotics enhance serotonin activity |

| Glutamate12–14 | Valproate, lamotrigine, and some antidepressants modulate glutamate transmission; rapid alleviation of depressive symptoms with ketamine infusion |

| Intracellular signalling | |

| Inositol monophosphatase15,16 | Lithium, valproate, and carbamazepine reduce intracellular myoinositol concentration and increase neuronal growth cone spreading at therapeutic concentrations |

| GSK-314,17 | Neuroprotective effects of lithium and other agents might be mediated by inhibition of GSK-3 |

| Protein kinase C pathway18 | Lithium and valproate inhibit PKC activity; tamoxifen inhibits PKC activity and might be antimanic |

| Calcium channels17 | CACNA1C risk allele associated with bipolar disorder; lamotrigine inhibits voltage-activated calcium channels; calcium channel blockers might be antimanic |

| Neural mechanisms | |

| Corticolimbic emotion control circuit19 | Hyperactivation of amygdala and reduced anterior cingulate activity during mania; reduced ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activity and hyperactivation of basal ganglia across mood states; reduced resting state connectivity of amygdala and prefrontal regions |

| Sleep and circadian regulation | |

| Circadian clock associated with impaired sleep and weight changes20–22 | Antipsychotics, lithium, and valproate regulate sleep and circadian rhythms and stabilise mood; interpersonal and social rhythm therapy is associated with delayed recurrences when social and circadian rhythms are regulated |

| Psychosocial variables | |

| Responses to stressful events23,24 | Negative events are associated with depressive episodes; goal attainment events are associated with manic episodes; psychosocial treatments can modulate responses to stress |

| High expressed emotion and negative family interactions23,25,26 | Crucial attitudes in caregivers and negative verbal interactions between caregivers and patients associated with greater likelihood of recurrence; family-focused therapy enhances family communication and is associated with reduction in mood symptoms |

| Drug adherence27–29 | Psychoeducational treatments improve adherence to mood stabilisers, leading to lower likelihood of manic recurrence |

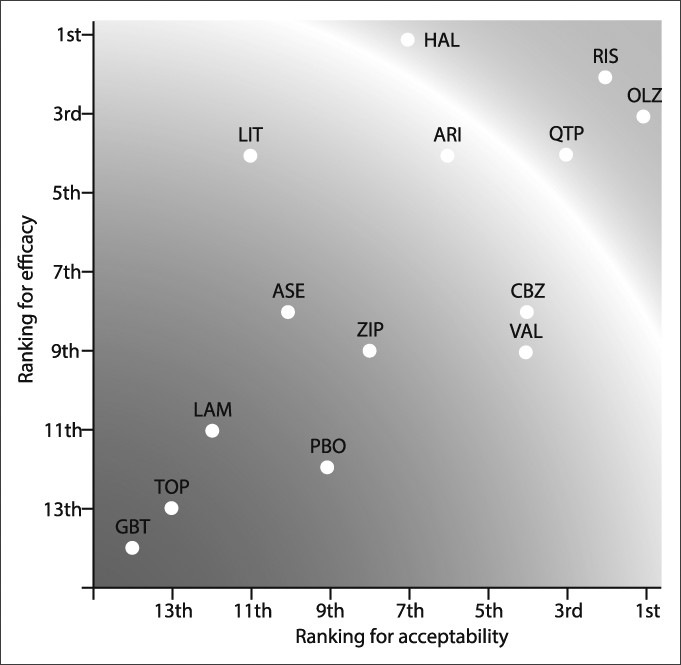

Treatment of Mania

Treatment of Bipolar Depression

Long-Term Maintenance Treatment

Psychosocial Treatments for Bipolar Disorder

| Sample size | Experimental treatment | Control treatment | Major outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEP-BD | ||||

| Miklowitz et al, 200760,61 | 293 adults | FFT, IPSRT, and CBT (up to 30 sessions) | Brief psychoeducation (3 sessions) | Patients given more intensive treatment recovered more rapidly from depression and stayed well for more months |

| Family-focused approaches | ||||

| Clarkin et al, 199862 | 33 adults | 25 marital psychoeducation sessions over 11 months | Treatment as usual | Better global functioning and drug adherence in patents given marital psychoeducation |

| Miklowitz et al, 200328 | 101 adults | FFT (21 sessions) | Crisis management (2 sessions) | FFT associated with delayed recurrences and lower symptom severity over 2 years |

| Rea et al, 200363 | 53 adults | FFT (21 sessions) | Individual psychoeducation (21 sessions) | FFT associated with delayed recurrences and fewer hospitalisations over 2 years |

| Miklowitz et al, 200864 | 58 adolescents | FFT (21 sessions) | Brief psychoeducation (3 sessions) | FFT associated with more rapid recovery from depression and less severe symptoms of depression over 2 years |

| Miklowitz et al, 201365 | 40 children and adolescents | FFT (12 sessions) | Brief psychoeducation (1–2 sessions) | FFT associated with more rapid recovery from depression, less time ill, and less severe manic symptoms over 1 year |

| Perlick et al, 201066 | 46 family caregivers of adult patients | FFT-health promoting intervention (12–15 sessions) | 8–12 health education sessions | FFT associated with greater decreases in caregiver depression and health risk behaviour and greater reductions in symptoms of depression in patients over 4 months |

| Multifamily groups | ||||

| Miller et al, 200867 | 92 adults | Single family treatment, multifamily group psychoeducation | Treatment as usual | No group differences in primary analyses; patients with impaired families had greater decreases in depression in both family treatments than in treatments as usual |

| Reinares et al, 200868 | 113 adults | 12 weekly caregiver group sessions over 3 months | Treatment as usual | Over 15 months, fewer patients whose caregivers attended groups had manic or hypomanic relapses |

| Fristad et al, 200969 | 165 children (ages 8–11 years) | 8 multifamily group sessions | 6-month waiting list | Children with mood disorders assigned to multifamily groups showed greater mood improvement over 6 months than did children on the waiting list |

| CBT | ||||

| Cochran et al, 198470 | 28 adults | 6 weekly individual sessions | Drugs only | CBT associated with fewer hospitalisations by 6 months |

| Lam et al, 200571 | 103 adults | 12–18 individual sessions of CBT | Minimal psychiatric care | Fewer depressive relapses and better social functioning in patients given CBT over 24–30 months |

| Ball et al, 200672 | 52 adults | 20 weekly sessions in 6 months | Treatment as usual | Less severe depression scores in CBT at 6 months, but not 18 months |

| Scott et al, 200673 | 253 adults | 22 sessions in 26 weeks | Treatment as usual | No differences in time-to-recurrence over 18 months; subgroup of patients with <12 episodes had longer time-to-recurrence in CBT |

| Zaretsky et al, 200874 | 79 adults | 20 weekly sessions | Individual psychoeducation (7 sessions) | No group differences in relapse rates over 1 year; 50% fewer days of depressed mood in CBT |

| Parikh et al, 201275 | 204 adults | 20 weeks of individual CBT | 6 sessions of group psychoeducation | No differences in relapses or symptom severity over 18 months |

| Meyer & Hautzinger, 201276 | 76 adults | 20 sessions over 9 months of CBT | 20 sessions over 9 months of supportive treatment | No differences in relapse rates over 33 months |

| IPSRT | ||||

| Frank et al, 200821 | 175 adults | Weekly sessions during acute treatment until recovered, monthly during maintenance treatment | Active clinical management (same frequency) | IPSRT during acute phase associated with longer time to recurrence during maintenance phase |

| Swartz et al, 201277 | 25 adults with bipolar II depression | Weekly sessions for 12 weeks (no drugs) | Quetiapine monotherapy 25–300 mg | No differences in depression response rates over 12 weeks |

| Group psychoeducation | ||||

| Colom et al, 2003, 200929,78 | 120 adults | 21 weekly structured group psychoeducation sessions | 21 weekly unstructured group sessions | Lower recurrence rates in structured groups over 5 years |

| Torrent et al, 201379 | 239 adults | 21 weekly sessions of functional remediation | 21 group psychoeducation sessions or treatment as usual | Functional remediation associated with improved functional outcomes compared to usual treatment |

| Weiss et al, 200780 | 62 adults with comorbid substance misuse | 20 weekly sessions of integrated cognitive behavioural groups | Drug counselling groups | Fewer days per month of alcohol use but more severe mood symptoms in integrated groups |

| Individual psychoeducation | ||||

| Perry et al, 199981 | 69 adults | Seven to 12 sessions of individual psychoeducation | Routine care | Increased time-to-manic-recurrence and improved social-occupational functioning in individual psychoeducation |

| Systematic care management | ||||

| Simon et al, 200682 | 441 adults | 2 year multicomponent intervention | Care as usual | Decreased severity and duration of manic episodes |

| Bauer et al, 200683 | 306 adults | 3 year multicomponent intervention | Care as usual | Decreased duration of manic episodes, better social functioning and quality of life |

Adjunctive Psychotherapy in Acute Treatment

Adjunctive Psychotherapy in Long-Term Maintenance

Family-Focused Therapy

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy

Group Psychoeducation

Functional Remediation

Systematic Care Management

Future Directions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).