Suicide rates have seen an upward trend among youths in recent years, roughly doubling between 2007 and 2017.

1–3 In 2019, suicide was the second leading cause of death among American adolescents aged 13-18, and the fifth leading cause of death in preadolescents aged 6 to 12 years.

4 Black American children are disproportionately affected in the younger age group, dying by suicide at a rate roughly double that of their White counterparts, with many potential contributors, including disproportionate exposure to violence, earlier onset of puberty, and diminished access to mental healthcare.

5–7 To understand this racial imbalance in suicide deaths, there is a need to study specific stressors that have a disproportionate impact on Black American preadolescents in the United States, such as the experience of racial/ethnic discrimination.

Racial/ethnic discrimination—poor and unfair treatment due to one’s race (groups of people with shared physical characteristics often associated with customs/origin) or ethnicity (groups of people with shared customs/origin)

8—is a social product of racism that can be experienced in multiple facets of life and may underlie the significant racial health disparities across the lifespan for many minority groups.

7,9,10 It is known that Black Americans experience significant amounts of racial/ethnic discrimination across the lifespan,

11,12 which has consistently been shown to associate with poor health outcomes.

13–17 Preliminary research has extended this work to mental health and suicidal ideation,

18–20 with similar effects observed across minority groups.

21 However, the specific role of racial/ethnic discrimination on suicidal ideation or attempts (ie, suicidality) in children, especially preadolescents, has yet to be established strongly and independently of other environmental adversities.

Determining the unique contribution of racial/ethnic discrimination to suicidality in youths is difficult for many reasons. First, racial/ethnic discrimination is highly correlated with other environmental adversities that have negative impacts on mental health, such as poverty, trauma, family conflict, and other hardships.

9,22–26 This web of intertwined environmental exposures, both specific (ie, childhood trauma) and general (ie, neighborhood environment), composes the

exposome, which has major implications for both mental and physical health.

27–29 Second, racial/ethnic discrimination may be associated with other forms of discrimination related to xenophobia,

30 sexual orientation,

31 and weight,

32 complicating the ability to tease apart the effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on suicidality from that of other discrimination types. Finally, racial/ethnic discrimination is associated with other (non–suicide-specific) psychopathology, including depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and substance use disorders,

19,33 which are risk factors for childhood suicidality.

34 Hence, identifying the specific effects of racial/ethnic discrimination on childhood suicidality requires multiple measures that include deep phenotyping of children’s environment and psychopathology.

Discussion

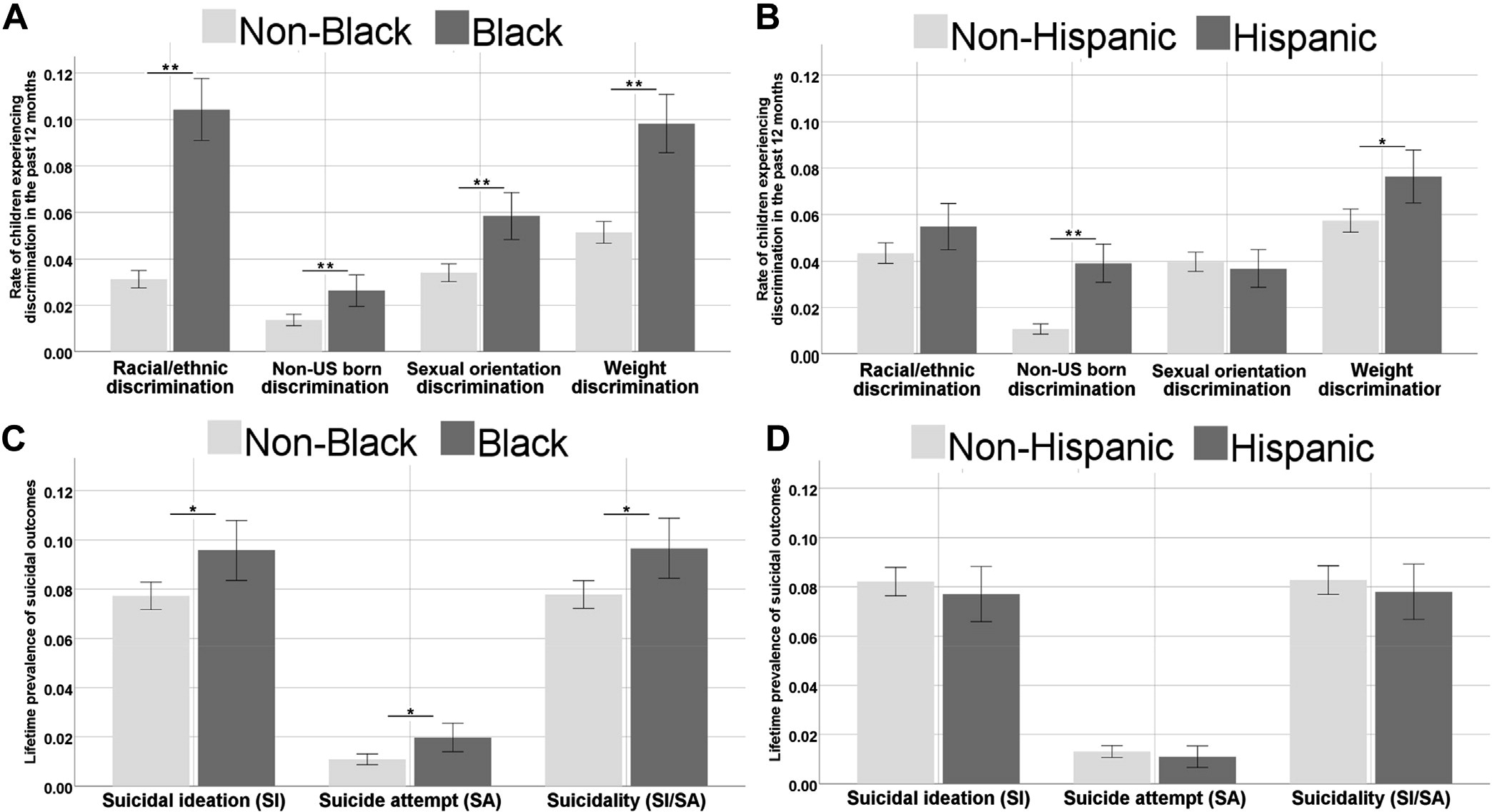

In this study, we investigated the association of racial/ethnic discrimination with preadolescent suicidality. In line with recent literature, we observed that Black American youths in the ABCD Study report higher levels of racial/ethnic discrimination and display more suicidality than other racial groups.

9,11 Notably, we found that Black children experience disproportionate amounts of

all studied forms of discrimination (toward non–US-born individuals, sexual orientation–based, and weight-based) compared to non-Black children—a finding that, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been documented in a large sample of American children. Multivariate analyses revealed that racial/ethnic discrimination is a unique contributor to suicidality in American youths, independent of other known environmental risk factors for suicidality, including negative life events,

23 family conflict,

34 other discrimination types (ie, sexual orientation–based),

31 and psychopathology.

25,43 Furthermore, although racial/ethnic discrimination is disproportionately experienced by Black children, its association with suicidality is similar in non-Black children. This association became nonsignificant when Asian, American Indian, and Native Hawaiian participants were examined independently, although this is likely due to insufficient power because of their smaller sample size among the ABCD Study’s participants. These findings suggest that racial/ethnic discrimination is a major stressor uniquely associated with preadolescent suicidality.

The assessment of discrimination in the ABCD Study included items related to 4 different domains: racial/ethnic; toward non–US-born individuals; sexual orientation–based; and weight-based. Our main analysis examined the association of racial/ethnic discrimination with suicidality, controlling for key demographic factors as well as other forms of discrimination and their associated identities (ie, non–US-born, LGBT, obese/underweight). We found that racial/ethnic discrimination imposes a unique psychological stress that is significantly associated with childhood suicidality with a magnitude of effect similar to well-established risk factors such as sexual orientation–based discrimination

31 and weight-based discrimination.

32 Notably, the data analyzed in the current study were collected in 2018, two years before the COVID-19 pandemic, post-election furor, and the prominent racial justice protests of 2020 to 2021; therefore, our findings may have been even more pronounced had the data been collected more recently, in 2021.

A fundamental challenge of studying environmental effects on health outcomes is that they are often colinear, and it is difficult to disentangle the unique effect of any specific stressor. The exposome framework embraces the inherent complexity of the environmental network rather than focusing on a single adversity (eg, trauma), examining environmental exposures within dynamic interactive domains.

28,29 The large sample size and deep phenotyping of the ABCD Study cohort provides an opportunity to dissect the specific components of the exposome and their interactions with race. Such has been extensively studied by Assari

et al., who have highlighted racial discrepancies in the effects of environmental protective factors.

44,45 Similarly, we sought to test the association of racial/ethnic discrimination on suicidality within the scope of the exposome. Discrimination was significantly correlated with adverse exposome and psychopathology measures, both of which are documented risk factors that may inflate its effect size on suicidality. However, racial/ethnic discrimination remained strongly associated with suicidality even when accounting for environmental adversity—poverty, low socioeconomic status, negative life events, family conflict

9,22,24,26—and non-suicide psychopathology, represented by diagnoses of both internalizing and externalizing domains.

25,43 It is important to note that items related to NSSI were not included. Although NSSI and suicidality are highly related, there is evidence that they have distinct etiologies, and the relationship between the them is complex and beyond the scope of this analysis.

46 Regardless, results highlight the burden that racial/ethnic discrimination has on mental health in childhood, demonstrating its effect over and above other environmental exposures.

A major finding that we report here is that once racial/ ethnic discrimination is experienced, it seems to retain its deleterious association with suicidality across races and ethnicities (ie, in both White and Black children, and in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic children). Our matched analyses allowed us to inspect the role of discrimination versus that of race in association with suicidality. When high discrimination participants were matched to low discrimination participants at every other variable, we found that high racial/ethnic discrimination was robustly associated with elevated levels of suicidality. However, when Black participants were matched to White participants at every other variable, there was no significant association between Black race and suicidality. Our findings resonate with a recent study by Matheson

et al., which found consistency in the effect of discrimination on mental health in various groups that have been historically marginalized, including Indigenous peoples, Black individuals, Jewish individuals, and women.

21Our findings have some immediate implications for clinicians and suicide researchers. We demonstrate that experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination are significant stressors whose magnitude of association with increased suicidality is similar to that of well-established risk factors such as sexual orientation–based discrimination

31 or history of depression.

43 Therefore, clinicians should be mindful of this unique stressor and consider this as a potential contributor to suicide risk. Notably, if a clinician decides that it is worthwhile to bring up racial/ethnic discrimination in a clinical evaluation, it should not be limited to Black children or children of other minority groups; the results attest that non-Black children who feel racially/ethnically discriminated against also have a higher chance of endorsing suicidality compared to their counterparts who do not feel discriminated against. It is important, however, that any discussion regarding race/ethnicity be done with care to avoid further mental anguish, as racial issues can be mentally burdensome, potentially traumatic topics for affected children if not handled with sensitivity.

12,47The current findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First and foremost, it is important to address the limitations with the measures used to assess racial/ethnic discrimination. In the 7-item discrimination measure used in main analyses, only the first 4 items refer specifically to ethnicity (defined by ABCD as “groups of people who have the same customs, or origin”), whereas the latter 3 items focus on feelings of marginalization/ostracization. This is in contrast to the binary variable assessing past 12-months’ experiences of racial/ethnic/color discrimination. However, although these concepts are nuanced and not perfectly equivalent, they are heavily entangled, and it is reasonable to assume that they were perceived by the study participants as strongly associated. This is reflected in the similar distributions of Black versus non-Black participants endorsing high racial/ethnic discrimination based on the 7-item measure (21.1% vs 8.6%) and racial/ethnic/color discrimination in the past 12 months (10.4% vs 3.1%). In addition, because racial/ethnic discrimination was measured using a 7-item matrix whereas other forms of discrimination were measured using a binary question regarding the past 12 months, the effect of racial/ethnic discrimination may be inflated over other discrimination types. Similarly, covariate identities based on assessed discrimination types were not exactly aligned. For example, the identity associated with discrimination toward non–US-born individuals was based only on whether or not the child was US-born, excluding first-generation Americans who may experience this same form of discrimination, and the identity associated with LGB included transgender individuals. Still, we show significant associations of multiple discrimination types with suicidality. We also demonstrate that racial/ethnic discrimination retains its robust association with suicidality even when accounting for many confounders in sensitivity analyses, suggesting that despite the limitations above, our findings add a timely and important perspective on the factors contributing to the growing problem of preadolescent suicidality.

Another concern is the personal characteristics of the high racial/ethnic discrimination sample. One may argue that the observed association between discrimination and suicidality may be inflated by poor self-esteem, low socioeconomic status, family neglect, or negative outlook, which may cause a participant to feel more highly discriminated against. We believe that this concern is greatly mitigated by the fact that the discrimination–suicidality association remained significant even after rigorous covariation for demographic and socioeconomic factors, as well as environmental adversity. The association was also significant in models that accounted for prodromal psychosis symptoms, depression, and anxiety, mitigating the concern that underlying psychopathology explains this discrimination–suicidality association. When other discrimination, environmental adversity, and psychopathology factors were covaried for in the same model, however, findings were nonsignificant (

p = .091). This suggests that there is some non-overlapping shared variance between these domains that warrants further investigation in future longitudinal studies. In addition, heterogeneity within assessed groups, especially “White” participants, may skew findings and limit generalizability. For example, selfidentified “White” race often includes minority groups (eg, Middle Eastern–descent, Muslim, and orthodox Jewish individuals), which may inflate instances of self-reported discrimination.

21,48 Moreover, participants are recruited from sites across the United States, where amount and type of discrimination may vary based on demographic composition of the area and associated study population. The study’s cross-sectional design also limits causal inferences between self-reported discrimination and suicidality. Nonetheless, the rigorous inclusion of confounders often associated with racial/ethnic discrimination and the matched analyses underscoring its unique effect support the directionality of the association from discrimination to suicidality. Future longitudinal studies are needed to clarify causal pathways in this cohort and others.

In conclusion, we report that the subjective experience of racial/ethnic discrimination is robustly and independently associated with suicidality in children, regardless of race or ethnicity. Findings suggest that race itself is not associated with suicidality but, rather, the experience of discrimination associated with belonging to a minority racial/ethnic group in the United States is the factor that contributes to suicidality. Black American children, however, are disproportionately exposed to racial/ethnic discrimination and therefore bear a disproportionate psychological burden. These findings may imply that care providers should be aware of discrimination’s detrimental effect on childhood mental health. Finally, although we focus on a US sample, such discrimination is likely present in other countries with multiracial/multiethnic populations, which merits further investigation globally.