To the Editor: Symptoms of catatonia,

1 including stereotypy, echophenomena, mutism, and perseveration, may overlap with those of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), which can lead to mistaken diagnoses.

2,3 In addition, catatonia can also be a presenting symptom of bvFTD.

4 We report a case with a complex differential diagnosis between persistent residual catatonia symptoms and bvFTD, and we review the approach to this neuropsychiatric challenge.

Case Report

A 55-year-old man was evaluated at the Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry Clinic of McLean Hospital and subsequently at the Frontotemporal Disorders Clinic of the Massachusetts General Hospital for a 3-year history of cognitive decline concerning for bvFTD. The patient graduated from an Ivy League school and worked as a lawyer before the onset of his symptoms. The patient’s past psychiatric history was significant for longstanding bipolar I disorder, which was well controlled with lithium. There was a strong family history of bipolar disorder but no frontotemporal dementia (FTD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or early onset dementia.

In 2011, the patient was admitted for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Lithium was discontinued, and treatment with prednisone and azathioprine was initiated. The patient recovered kidney function but developed delirium and suicidal thoughts. Olanzapine and lamotrigine were started, with limited response. After the patient received haloperidol, he developed catatonia (immobility, mutism, and negativism), which improved with lorazepam. The collateral report of the patient’s functional decline 1–2 years before he developed glomerulonephritis (disorganization at work leading to mistakes) and cognitive impairment with predominant executive dysfunction on neuropsychological testing raised concern regarding progressive dementia, with a working diagnosis of possible FTD.

The patient subsequently had multiple episodes of depression, with suicidal thoughts alternating with retarded catatonia. Eighteen months after the glomerulonephritis, he was hospitalized in a community hospital for acute confusion and aphasia (paraphasias and word-finding problems). A brain MRI scan showed no acute abnormality. A routine EEG was normal. Repeat neuropsychological testing revealed executive dysfunction, including impairments on word-list generation. Aphasic symptoms improved within a few days. However, in light of persisting functional and cognitive decline, the patient was discharged with a final diagnosis of FTD.

On our initial assessment, the patient and his wife acknowledged persistence, but denied progression, of cognitive deficits. He had failed to resume his law practice and was caught driving through red lights a few times. His wife reported apathy and a new simple stereotypical breathing sound but no disinhibition, socially inappropriate behavior, or hyperorality. There was no change in empathy, but she described a longstanding history of social awkwardness, visuospatial weaknesses, and clumsiness. He had adequate social comportment. The patient’s forward digit span was 8, but his backward digit span was only 3. He scored 26 on 30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (z score=0.5), losing most points on visuospatial tasks. His Frontal Assessment Battery was impaired at 9 on 18 (z score=−9.4), including decreased verbal fluency (phonemic 6, semantic 13) and impaired go/no go. Language was relatively preserved. On neurological examination, the patient had mild motor perseveration and psychomotor slowness but no frank catatonic features such as mutism or waxy flexibility. Six months later, the patient was more apathetic, made occasional paraphasic errors, and had more pronounced fluency deficits (named two animals in 1 minute). His cognitive deficits were too severe to be solely explained by a chronic bipolar disorder. The differential diagnosis was between bvFTD and residual symptoms of catatonia. Atypical features for bvFTD included good insight and fluctuations of language symptoms. Developmental nonverbal learning weaknesses were a potential contributor.

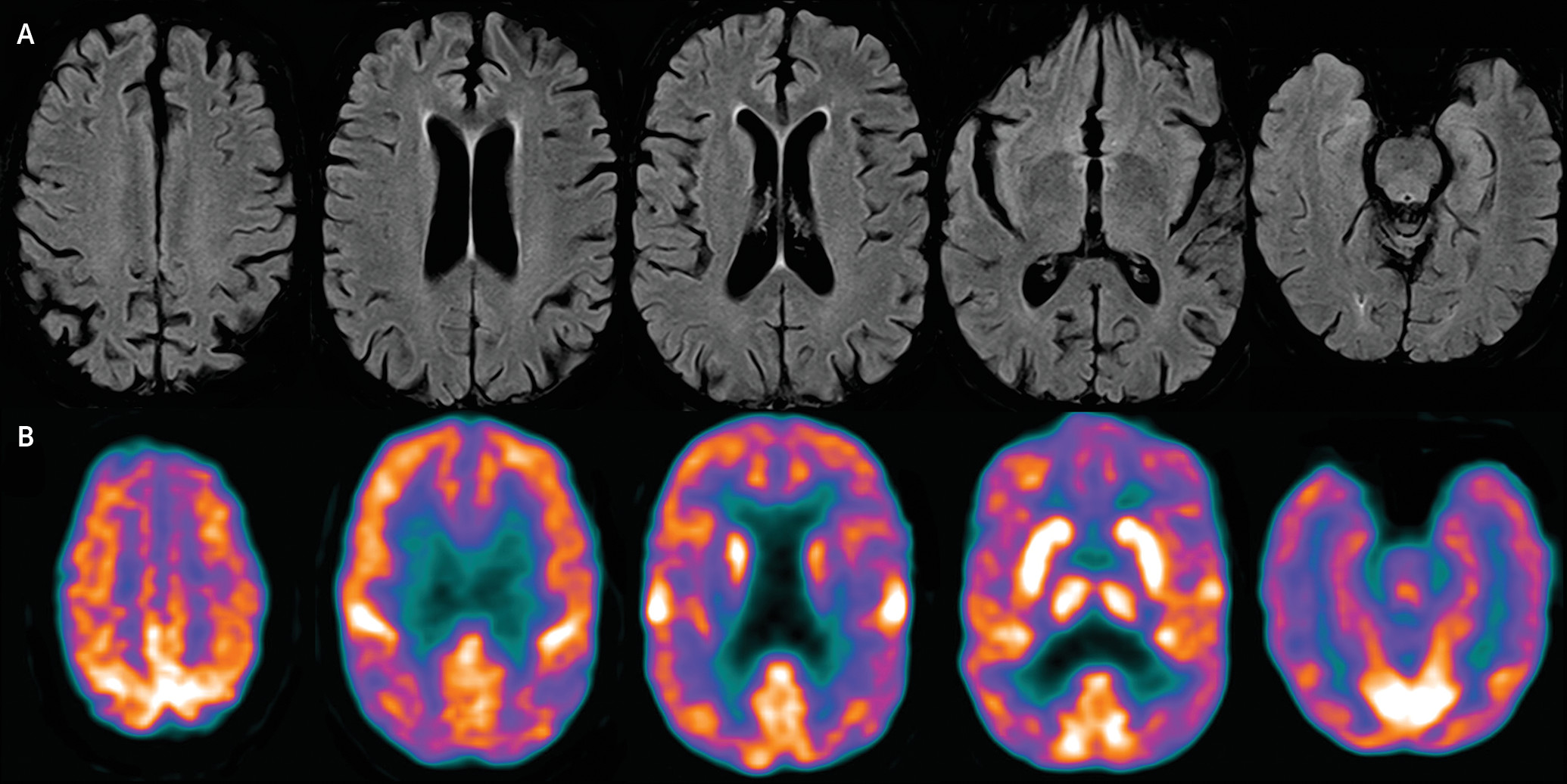

A biochemical workup including a paraneoplastic panel was normal. A CSF analysis showed normal cell counts and mildly low Aβ42 (272 pg/mL) but normal P-tau (28.6 pg/mL). A brain MRI scan showed mild diffuse volume loss, with no predominant frontal or anterior temporal atrophy and no change over an 18-month period (

Figure 1 [A]). Fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography showed no definite regional cerebral cortical hypometabolism to suggest a specific neurodegenerative process such as FTD or Alzheimer’s disease. There was subtle patchy hypometabolism in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, which was of uncertain clinical significance (

Figure 1 [B]).

After 1 year of treatment with divalproex sodium and 4 mg of lorazepam daily, the patient’s mood stabilized with no recurrence of catatonia. He was not able to resume working, but he regained independence for all instrumental activities of daily living. At the last follow-up, there were no persistent language deficits or behavioral symptoms. The patient’s Frontal Assessment Battery score improved to 13 of 18 (z score=−5; 44% improvement). His fluency remained impaired but improved (phonemic 5, semantic 11). The remission of behavioral symptoms, improvement of executive functions, and neuroimaging results were incompatible with bvFTD. In retrospect, behavioral symptoms and acute aphasia were attributed to fluctuating catatonic states in the context of unstable bipolar I disorder after a medical illness.

Discussion

As illustrated by this case, there can be phenotypic overlap between catatonia and bvFTD, suggesting shared frontostriatal dysfunction.

5 In addition, decreased verbal output and stereotypical repetition due to catatonia can be confused with aphasia. Verbal fluency/generation was the main cognitive deficit in our patient, a function that is mediated by the dorsal medial frontal system.

6 Of interest, one functional MRI study linked catatonia to abnormalities of this area.

7Longitudinal history, response to treatment, and neuroimaging help to establish the correct diagnosis. Catatonia is much more likely to fluctuate over time in parallel to the underlying causative disorder (e.g., bipolar disorder), whereas the course of bvFTD is one of inexorable progressive deterioration. Along the same line, rapid improvement of cognitive symptoms after lorazepam administration would suggest catatonia.

Changes on imaging can be subtle in the early stages of bvFTD; however, neuroimaging correlates are expected when a patient has late-stage symptoms such as mutism and immobility. A normal MRI scan in the presence of severe symptoms would favor a diagnosis of catatonia. Small studies have described frontoparietal hypometabolism/hypoperfusion in catatonia,

8,9 which is potentially reversible after treatment.

9 As our case suggests, a mildly abnormal positron emission tomography scan does not exclude catatonia secondary to a primary psychiatric disorder.

In our patient, executive function deficits (most severely generation) persisted despite long-term mood stability. There is one report of persisting cognitive deficits after remission of catatonia,

10 and our case adds to this literature. We postulate that partial remission, or persistent cognitive symptoms, of catatonia could explain some cases of nonprogressive bvFTD “phenocopies.”