Mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) is common among children and adolescents, accounting for >600,000 annual emergency department visits in youth 0–19 years old in the United States.

1 Although mild TBI causes transient disruption in neurological functioning, substantial evidence demonstrates that the prognosis is good. Methodologically rigorous studies have not detected lasting neurocognitive sequelae of a single uncomplicated mild TBI (i.e., injuries without obvious neuroimaging pathology), particularly when outcome is measured with objective, performance-based tests.

2–5 However, a small subset of pediatric patients report persisting postconcussive symptoms or problems.

6,7 Injury-related factors account for some of the variance in outcome,

8 but their effects tend to diminish with time, suggesting that other noninjury factors play an important role in persistent symptomatology.

9 Mounting evidence highlights the importance of preinjury functioning in mild TBI recovery.

5,9–11 This study aims to add to this literature by exploring premorbid emotional-behavioral functioning in a case series of children and adolescents referred clinically for concerns about lingering problems after mild TBI.

A small body of research has specifically examined the influence of preinjury emotional-behavioral functioning on outcome after pediatric mild TBI. Results consistently show that preexisting emotional-behavioral problems (as measured retrospectively by parent-report questionnaire) predict more problems after mild TBI, even after controlling for injury-related and demographic variables.

5,9–11 Preinjury emotional functioning and outcome after mild TBI are likely linked in part because “postconcussive” symptoms are nonspecific and overlap substantially with symptoms of depression, at least in adults.

12 Furthermore, postconcussive symptoms include somatic complaints (e.g., stomach upset or headache), which have been linked to anxiety and depression in children.

13,14Mild TBI, like other types of childhood injury, is not randomly assigned in the population. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and related externalizing problems are at increased risk for unintentional injury,

15–17 including mild TBI. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and externalizing disorders commonly co-occur with emotional and learning disorders

18; therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that as a group, injured children show higher rates of neurobehavioral problems.

3 In general, research supports the conclusion that symptoms of impulsivity or behavioral dysregulation place children at risk for exposure to mild TBI, and not that mild TBI causes symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

4,19 at least for children with uncomplicated injuries. Relatively more severe mild TBI (e.g., injuries requiring overnight hospitalization) might convey some risk for later symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, especially in younger children,

20 although more work is needed to clarify this issue. It is also possible that preexisting cognitive problems could complicate children’s ability to recover from a mild TBI (similar to the role that reduced cognitive reserve has been shown to play in cognitive aging),

21 providing yet another basis for a link between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and postconcussive problems.

22The goal of this study was to build on this previous literature by characterizing the preinjury emotional-behavioral functioning of children aged 8–17 years who were clinically referred to an outpatient pediatric concussion program, generally because of concerns about persisting problems related to a mild TBI. We also investigated associations between emotional-behavioral problems and a history of mild TBI before the presenting injury to gain more information about risk factors for mild TBI exposure. We expected that externalizing problems would be related to exposure to injury, consistent with previous research. In addition, we predicted modest elevations in rates of clinically significant preinjury internalizing problems in our sample, which is heavily selected for postconcussive problems.

Discussion

In stark contrast with children who sustain a severe TBI, which can profoundly alter their developmental trajectories, most children recover quickly and well after a mild TBI. However, a minority of pediatric patients reports lingering postconcussive problems, including physical (e.g., headaches), cognitive (e.g., distractibility), and emotional (e.g., irritability) symptoms.

7 The basis for protracted recovery after mild TBI has been a source of longstanding controversy,

31 with disagreement centering on whether problems are of primarily “psychogenic” or “physiogenic” origin. Clearly, this debate oversimplifies the key questions. First, it implies that problems must be of exclusively physiological or psychological origin. Second, it sets up a false dichotomy; because the brain is the organ of all behavior, even indirect effects related to stress or emotional concerns must be neurologically mediated. Researchers have recently begun moving beyond these oversimplifications by attempting to account for both injury-related and noninjury-related factors in outcomes after mild TBI.

9–11 This study highlights the importance of one noninjury-related factor—premorbid emotional-behavioral functioning—in understanding persistent problems after pediatric mild TBI.

We found that the rate of preinjury anxiety was elevated in this sample of children with lingering postconcussive problems, echoing a recent finding in adults.

32 We believe that there are several reasons why premorbid anxiety could potentially place children at risk for prolonged recovery after mild TBI. Anxiety and somatic symptoms are closely linked in pediatric populations, including symptoms that overlap with “postconcussive” problems (e.g., headaches or stomach upset).

13,33 Shortly after mild TBI, anxious children and/or their parents may misattribute some of these symptoms to injury effects, similar to what has been shown in adults.

34 Furthermore, children with anxiety are more likely to be hypervigilant to pain and other physical problems that would be expected in the initial days or weeks after mild TBI.

35 This hypervigilance may in turn exacerbate both their physical discomfort and their anxiety, creating a positive feedback loop. Children with anxiety are less likely to use adaptive coping skills in the face of a stressor, such as an injury.

36 These children might be especially vulnerable after mild TBI because of fears that they have suffered permanent brain damage and may never fully recover, consistent with research showing that illness perception affects recovery from mild TBI in adults.

37 Of course, these possibilities are not mutually exclusive. To begin to disentangle their relative contributions, future outcome studies on mild TBI should include more specific measures of health-related anxiety. In addition, future research could compare anxious children who sustain a mild TBI with anxious children who sustain injuries not involving the head, or future studies could more specifically examine how anxious children who have sustained a mild TBI perceive and cope with their injuries.

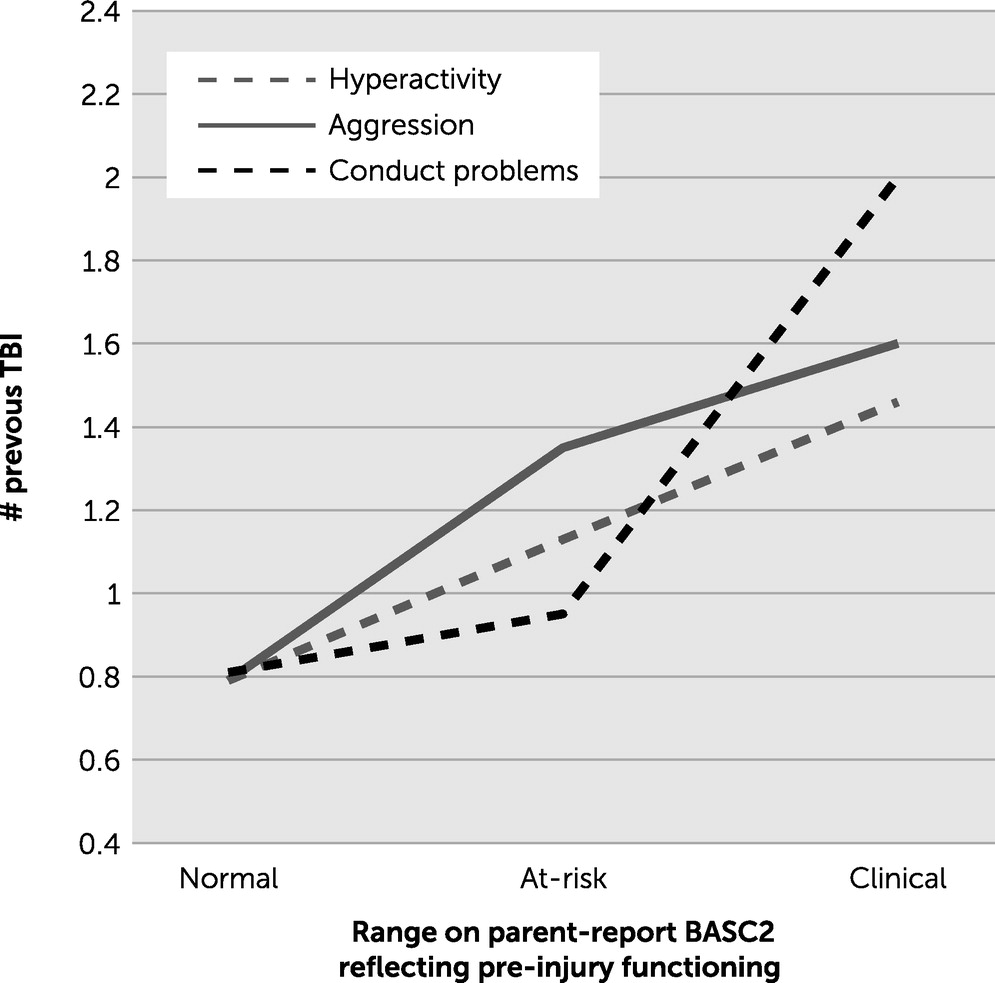

We also found confirmatory evidence that externalizing problems are linked to exposure to mild TBI. Children with clinically significant externalizing problems before the presenting injury had sustained, on average, nearly twice as many previous mild TBIs compared with children with normal-range externalizing problems. Because information about previous injuries and externalizing problems was collected at a single time point, the current data do not speak to causal direction. It may be that impulsivity and other acting-out behaviors place children at risk for sustaining mild TBI. On the other hand, a history of multiple mild TBIs may convey some risk for elevated externalizing problems after injury. We believe that the former interpretation is likely primary, on the basis of previous research comparing children who sustain a mild TBI with those who sustain injuries not involving the head.

4,18 However, in our clinical experience, teachers or parents will sometimes attribute cognitive or learning difficulties to a recent mild TBI, even when the problems do not clearly represent a change from baseline or when functional changes are more likely to relate to shifting environmental demands such as a normal developmental increase in academic expectations (e.g., progressing from middle school to high school). Externalizing disorders are associated with academic and neurocognitive impairment,

38 and once again, there is overlap between the features of these disorders and postconcussive symptoms (e.g., distractibility). Finally, we found that the number of previous mild TBIs was associated with clinically significant levels of somatization. Again, the reason for this finding is ambiguous. It may be that children with more previous TBIs experience more persistent postinjury physical symptomatology. Alternatively, among children with a history of multiple TBIs, those with a tendency to somaticize may be more likely to seek neuropsychological consultation. Overall, these results also highlight the need to consider preinjury functioning in children who present with persisting concerns after a mild TBI.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of several additional limitations. First, we used a convenience sample of children who were clinically referred, which was not representative of the broader pediatric mild TBI population because most children recover quickly after injury and thus would not be referred for neuropsychological evaluation. Parents in this sample are almost certainly more concerned about their children’s functioning than are parents who do not seek neuropsychological evaluation for their children after a TBI. For this same reason, it is likely that our sample differs from an epidemiological mild TBI sample in various injury-related variables (e.g., mechanism of injury, number of previous mild TBIs, and likelihood of undergoing imaging). Second, emotional-behavioral functioning was rated retrospectively, which probably introduced a variety of biases. For example, parents could have updated their impression of the child’s previous functioning in light of current functioning, which might have caused them to over-report preinjury problems. Arguing against this concern is previous empirical demonstration of the “good old days” bias after a pediatric mild TBI, in which parents systematically under-report their children’s preinjury problems.

39 Some aspects of the current data are consistent with the “good old days” bias. Parents rated the average preinjury depression and attention scores in the current sample as essentially identical to national norms, despite reporting that nearly 20% of the sample had been formally diagnosed or treated for a depressive disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. We assume that relatively more objective, binary questions about diagnostic history are less likely to be biased than responses on a relatively more subjective, continuous questionnaire. Similarly, although externalizing problems were linked to a history of previous mild TBI, mean ratings for externalizing problems in the sample as a whole were close to national norms. It is important to note that the “good old days” bias acts conservatively in this study, because it makes it more difficult to detect preinjury emotional-behavioral problems. A third limitation was that preinjury emotional-behavioral functioning was assessed by a single rater (typically a parent), and we did not have self-report or teacher ratings. Finally, we did not have data for a control group of children with injuries not involving the head; therefore, comparisons were made relative to national norms instead. Thus, obtained differences could owe to differences between our sample and the norming sample on background characteristics, rather than effects specific to mild TBI.

Despite these limitations, our results make a novel contribution to the small body of work investigating the role of premorbid emotional-behavioral functioning in pediatric mild TBI outcome, and they have implications for both research and practice. From a research standpoint, these results highlight the need for outcome studies on mild TBI to rigorously account for preinjury emotional-behavioral functioning. Of course, prospective studies are optimal in this regard. Although previous prospective studies have been quite powerful in describing the natural history of mild TBI,

3,40 assessment of baseline emotional-behavioral functioning has typically been quite limited. When prospective designs are not feasible, researchers should consider using control groups that can help account for factors associated with exposure to injury (e.g., orthopedically injured controls).

From a clinical standpoint, our results suggest that providers should carefully consider preinjury emotional-behavioral functioning when evaluating and managing children with persistent problems after a mild TBI. For many children with persistent symptomatology, difficulties are unlikely to owe exclusively to direct, injury-related factors. Indeed, for anxious children, communicating the assumption that lingering problems reflect more severe neurological injury could have iatrogenic effects. Such children are likely to benefit most from reassurance from a brain injury perspective, along with cognitive-behavioral treatment focused on stress reduction, pain management, and positive coping strategies. On the basis of our findings, we also speculate that children with clinically significant anxiety might particularly benefit from psychoeducation immediately after a mild TBI and that targeted early interventions (e.g., relaxation training) could possibly help prevent the development of persistent postconcussive complaints in this population. These would also be fruitful questions for future research.