Participants

As part of a Department of Defense–funded study for assessing rTMS augmentation of CPT for PTSD, veterans from OEF, OIF, and OND with current symptoms of PTSD were recruited from the community to participate in the clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01391832). Briefly, the clinical trial involved random selection of veterans with PTSD to active versus sham 1-Hz rTMS to the right prefrontal cortex just before CPT to determine whether rTMS could augment the treatment effect of CPT. In addition, before treatment, as well as when treatments were completed, participants underwent magnetic resonance neuroimaging and EEG evaluations. Participants were recruited from the community, focusing on military installations, Veteran Affairs hospitals, veteran centers, local universities and colleges with veteran enrollment, and various nonprofit veteran-associated service organizations. Interested participants contacted the study team and were interviewed by telephone. Study coordinators provided information to the veteran and performed a brief screen of eligibility. Those who were interested in participating and met basic qualifications were brought in for a formal evaluation. The data for this study were acquired from February 2012 to February 2015.

Before any procedures or evaluation at the first visit, the study was reviewed with the participants in detail and all questions were answered. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (IRB of record) and the University of Texas at Dallas, as well as the Army Human Research Protection Office. Participants included male and female veterans of OIF/OEF/OND between 18 and 60 years old who had a current diagnosis of combat-related PTSD. Participants were recruited, screened, and included in the study in an unbiased fashion with regard to race, ethnicity, or gender. The data from the initial visit were used in this analysis to assess factors associated with functional status. Participants were permitted to continue their medications, including psychiatric medications, unless contraindicated for safety reasons. Veterans were excluded for a history of the psychiatric comorbidities of eating disorders, psychotic symptoms, and current (<3 months) substance dependence, primarily for concerns of potentially confounding the results. Other exclusionary conditions for primarily safety reasons included a history of a significant neurological/medical disorder (including seizure), traumatic brain injury (TBI) (moderate or severe), brain tumors, stroke, blood vessel abnormalities in the brain, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s chorea, multiple sclerosis, cardiac pacemaker, implanted medication pumps of any sort that would increase the risk for rTMS, history of significant heart disease (e.g., history of myocardial infarction, tachyarrhythmia, congestive heart failure, or valvular disease), or any metal objects in or near the head (most dental work was permitted) that could not be safely removed for TMS treatments. TBI was screened by both history and review for significant lesions indicative of TBI on the participant’s structural MRI scan obtained during the neuroimaging session. Veterans with greater than mild TBI (i.e., loss of consciousness >30 minutes, posttraumatic amnesia >1 day, penetrating trauma, or evidence of structural injury on MRI) were excluded. Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding were excluded. Non-English speakers were also excluded because some of the screening forms, questionnaires, and tests were only available in English. Veterans were also excluded if they were unable or unwilling to stop taking a prescription medication or illegal substances that significantly lowered the seizure threshold. Participants could not start any new psychological treatment for PTSD while being in the study.

Procedures

At the initial visit, participants provided baseline data, including filling out forms and being clinically evaluated by trained evaluators. Veterans also provided a urine sample for drug testing and pregnancy testing if applicable. If the participant was fatigued by the evaluation, he or she could finish the evaluation on a subsequent day.

Self-administered scales and information obtained were as follows. Demographic information including age, gender, race, education in years, and years of active duty was obtained. Participants filled out the following questionnaires: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Adult Safety Screen (TASS),

17 MRI Safety Screening Form, Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (IPF),

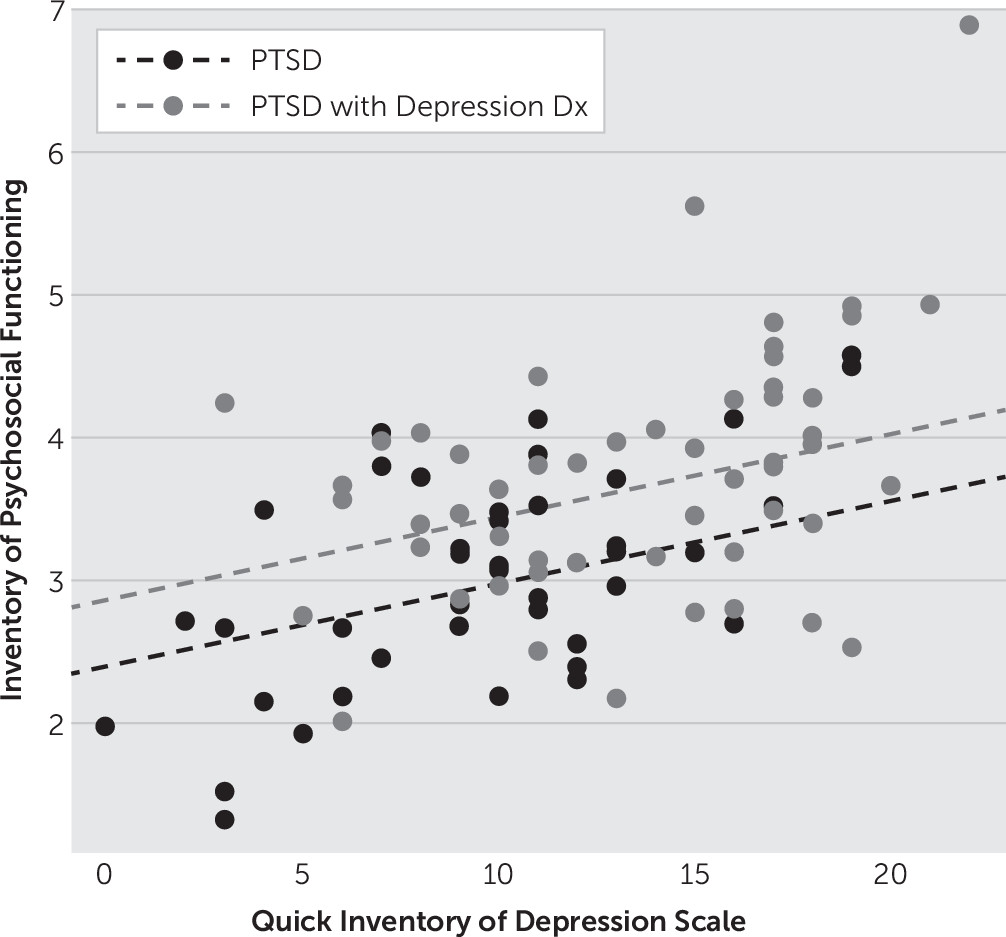

6 Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS),

18 Full Combat Exposure Scale (FCES),

4 and Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire (ACE).

19 The TASS and MRI Safety Screening Form were administered to ensure the patient’s safety in undergoing TMS and MRI, respectively. The QIDS assessed the severity of depressive symptoms using a 0–3 scale on each of the 16 items. Higher scores indicated greater endorsement of depressive symptoms. The ACE score consisted of 10 questions utilized to assess the participant’s degree of exposure to different categories of trauma during the first 18 years of life. Higher scores indicated greater exposure. The FCES consisted of 34 questions to measure the participant’s degree of exposure to combat-related traumatic events with higher scores indicating greater exposure. The IPF, an 80-item self-report measure that assessed functional impairment experienced by active-duty service members and veterans during the past 30 days, was scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 7 (“always”). The IPF provided a total score for each of seven subscales (romantic relationships with a spouse or partner, family relationships, work, friendships and socializing, parenting, education, and self-care functioning), and an overall functional impairment score was computed by calculating the mean of the scores for each completed (i.e., applicable) subscale. Thus, the IPF measures broad areas of functioning, including social and occupational functioning, in addition to self-care. Again, higher scores indicated a greater degree of impairment.

Clinician-administered scales were as follows. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

20 and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (axis I disorders)–Patient Version (SCID)

21 were administered by either a licensed psychologist or licensed professional counselor. The SCID was used to provide diagnostic classifications for patients with axis I psychiatric disorders based on DSM-IV-TR criteria. Although a diagnosis of current PTSD was obtained from the CAPS, the SCID was used to assess for the presence of comorbid disorders that may exclude a patient from the study. The CAPS was developed at the National Center for PTSD and has become the “gold standard” for assessing PTSD in individuals >15 years old. The CAPS consisted of 30 interview questions that targeted DSM-IV-TR criteria for PTSD. These items assessed core PTSD symptoms and related issues, as follows: re-experiencing symptoms, avoidance and numbing symptoms, hyperarousal symptoms, trauma-related guilt, dissociation, subjective distress, functional impairment, onset, duration, symptom severity, symptom improvement, and response validity. The evaluation provided a measure of symptom severity and sufficient criteria to determine whether a current or lifetime diagnosis of PTSD was valid.

Data Analysis

The variables of PTSD severity (CAPS), combat exposure (FCES), depression (QIDS), diagnosis of a depressive disorder, childhood adversity (ACE), TBI, substance use, number of combat-related traumatic events, age, gender, race, education in years, number of times deployed, years of active duty, and interactions of each quantitative predictor with each of gender, race, and diagnosis of a depressive disorder were investigated in multiple regression models to determine their contribution to the degree of functional impairment as measured by the IPF. A variable selection routine was utilized, which incorporated combinations of forward addition and backward elimination of variables until there was no further improvement in model diagnostics. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was the chosen statistic for the determination of the best model.