Case 1

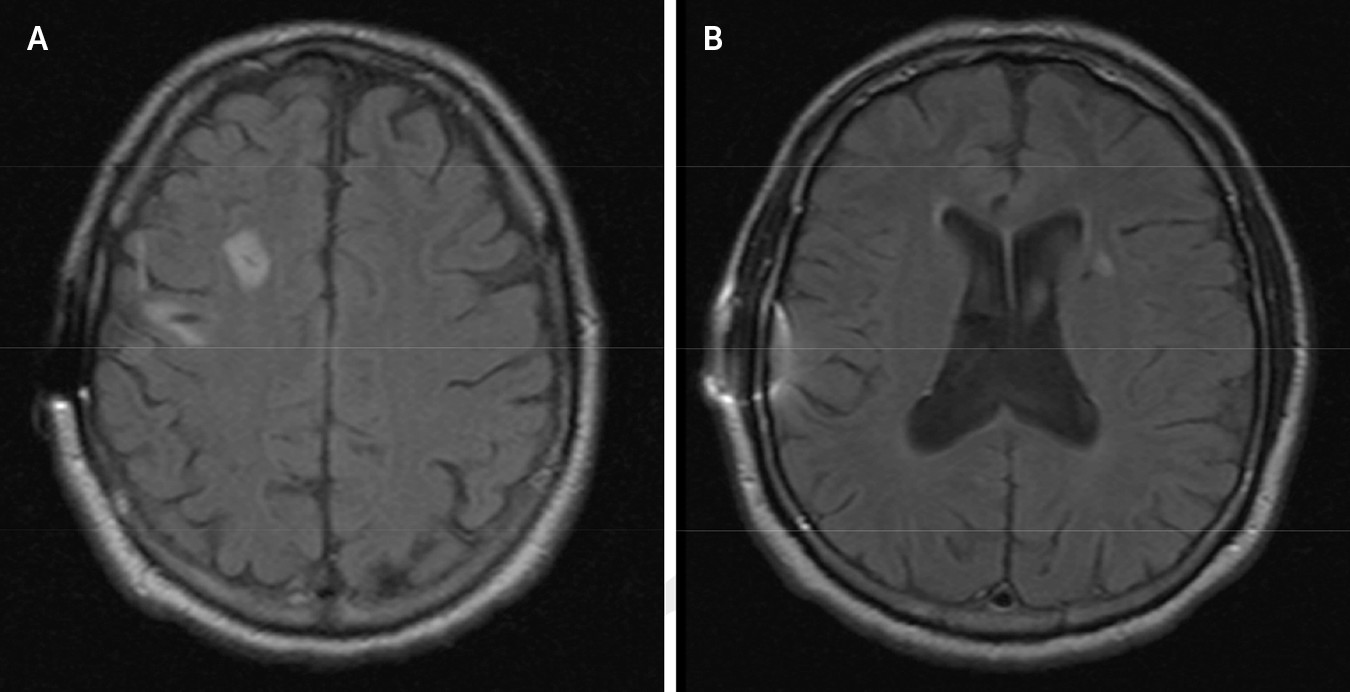

A 69-year-old right-handed man presented for a neuropsychiatric evaluation because of a 5-year history of compulsive joking. At 10 years before presentation, he had a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) of undetermined etiology. The SAH was complicated by hydrocephalus, placement of a right ventriculoperitoneal shunt, and a small area of perishunt encephalomalacia in the right frontal region (

Figure 1[A]). Afterward, the patient was left with a personality change. He became compulsive, with a fixation on recycling to the point where he would go through dumpsters searching for recyclable items. The patient also developed hoarding behaviors such as collecting napkins and utensils from restaurants and other locations.

At 5 years after this event, the patient again had a fairly abrupt behavioral change, this time with the development of constant joking as well as disinhibition. He became affectionate toward younger women, hugging them for “too long,” made borderline offensive comments, and took candy from stores without paying, getting caught on several occasions. A subsequent neurological evaluation with MRI revealed a new lacunar stroke in the head of the left caudate nucleus (

Figure 1[B]).

On interview, the patient reported feeling generally joyful, but his compulsive need to make jokes and create humor had become an issue of contention with his wife. He would wake her up in the middle of the night bursting out in laughter, just to tell her about the jokes he had come up with. At the request of his wife, he started writing down these jokes as a way to avoid waking her. As a result, he brought to our office approximately 50 pages filled with his jokes, most of which were either puns or silly jokes with a sexual or scatological content (

Table 1). The patient’s past medical history was positive for previous depression, absent for the preceding 10 years.

On examination, the patient had frequent episodes of joking with prominent laughter. Although he would laugh at his own jokes or witticisms, his laughter was neither uncontrollable nor involuntary. His Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 29 of 30 (he missed one recall item). The language examination result was normal, and he generated a list of 25 animals per minute and 24 “F” words per minute (including expletives). On memory testing, he was able to recall seven of 10 words on 15-minute delayed recall. He was intact on calculations, praxis, and frontal system tasks, but he misplaced the hands on a clock-drawing test. He had normal idiom and proverb interpretation, and he had full insight into his excessive joking behavior and humor. Results of the neurological examination were remarkable for some difficulty with tandem gait manifested as a subtle loss of balance. Neuropsychological testing showed difficulties in frontal-executive functions, such as response inhibition, self-monitoring, and task-monitoring.

On further testing, the patient showed increased humor production and normal identification of humor in jokes but a decreased affective appreciation of “funniness.” On a 24-point self-descriptive scale for sense of humor, the patient’s scores suggested significantly elevated humor creativity. On the Joke and Story Completion Test, a multiple-choice test of humor appreciation,

10,11 the patient was able to correctly identify the punchlines of 16 jokes. Despite his correct recognition of the funny endings, he did not laugh or report them as feeling funny. Additional testing with other jokes confirmed the same ability to identify the funny line but without laughing or experiencing it as funny.

The patient did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications and trazodone, but he had a partial response to 20 mg dextromethorphan/10 mg quinidine titrated to twice a day. While taking this medication, the patient had a significant reduction in the frequency and duration of his episodes of laughter but without any effects on his compulsive need to constantly make and tell jokes. He remained stable, without progression, with this regimen.

Case 2

A 57-year-old right-handed man presented for evaluation of a 3-year history of the insidious onset and progression of behavioral changes. The patient had become a “jokester,” always making childish jokes or comments and laughing easily at his own comments. He had also become disinhibited, saying or doing things that were inappropriate and demonstrating excessive familiarity with strangers. He lost his job after blurting out, “Who the hell chose this God-awful place?” In addition, without invitation, he would walk into his coworkers’ offices and defragment their computers or he would walk into a neighbor’s home and play the piano.

Further changes included prominent compulsive behavior, along with dietary changes and a decline in his hygiene. The patient’s wife found dozens of coffee grinders and almost two dozen Hawaiian shirts accumulated in their garage. He also had changes in his eating behavior, in which he would eat the exact same thing over and over again and became obsessed with certain fast foods. At one point, the patient had not bathed for at least 6 weeks; when he was asked to do so, his response was, “Chinese people don't have body odor” (he was of Asian descent). His past medical history was negative except for an appendectomy and tonsillectomy, and his family history was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, the patient would frequently break out in laughter, almost cackling, at his own comments, opinions, or jokes, many of which were borderline sexual or political in content. He scored 29 of 30 on the MMSE, missing only the exact day of the week. Language was fluent with good auditory comprehension, repetition, and confrontational naming. He generated a word list of 20 animals in 1 minute and 19 “F” words in 1 minute. On memory testing, he recalled zero of 10 words spontaneously at 15 minutes but recalled all 10 on a recognition task. He had very good memory for current events. The patient had normal performances on visuospatial, simple calculation, and ideomotor praxis tasks. He was concrete on some proverb interpretations, and he showed no insight into his disease or behavioral changes. Neuropsychological testing results showed that the patient had executive deficits and decreased memory retrieval. The rest of the neurologic examination was normal.

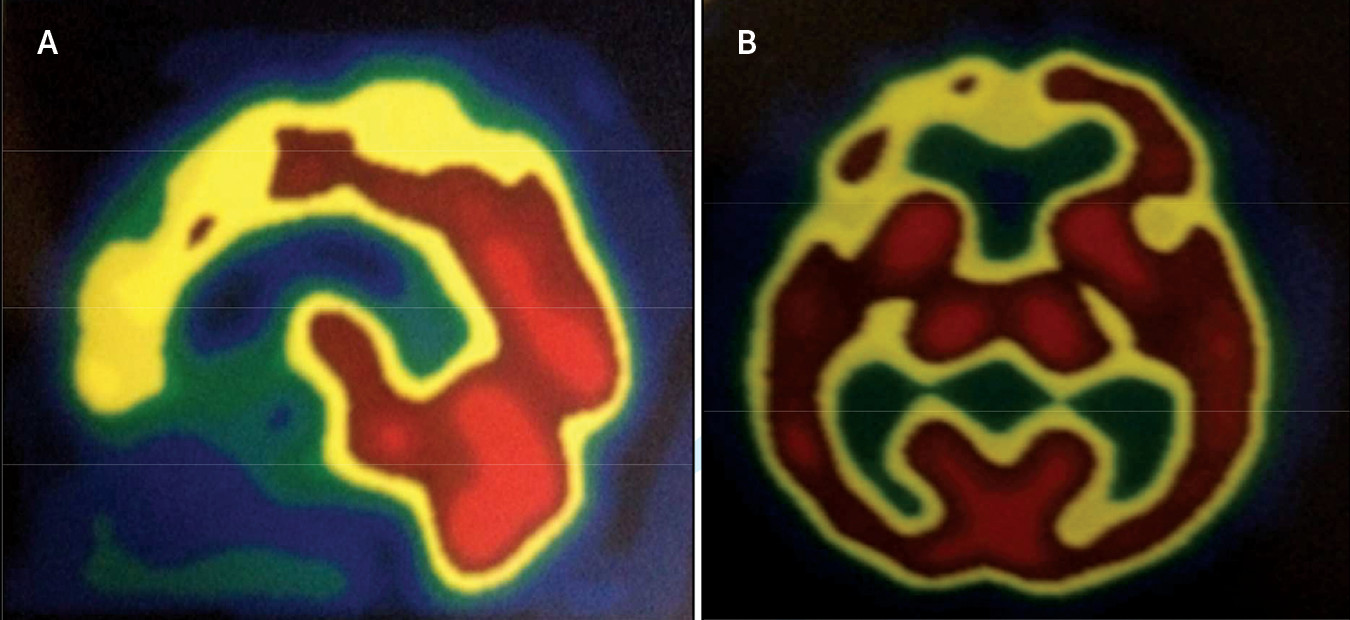

This patient had progressive behavioral changes consistent with bvFTD. Although results on MRI were within normal limits, brain single-photon emission tomography imaging results showed relative frontal hypoperfusion (

Figure 2). On subsequent follow-up visits, the patient continued to make frequent comments and jokes, at times acting quite silly, childish, and inappropriate. For example, on one clinic visit, he began disco dancing; on another, he publicly discussed his sexual situation; and at a third visit, he grabbed the examiner's tie and that of a passing physician and started to compare them. Throughout these behaviors, the patient would quickly lapse into laughter. Yet he did not laugh or consider funny any jokes or witticisms presented to him, despite being able to recognize most of the punchlines. He remained jovial despite trials of SSRI medications, and he continued to deteriorate in cognition and developed parkinsonism.

The patient died 11–12 years into his course, and his autopsy showed that he had Pick’s disease (a form of bvFTD). He had asymmetric frontotemporal atrophy, severe in the frontal lobes and moderate in the temporal lobes, affecting the right side more than the left. He had tau-immunoreactive intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with Pick bodies in neurons involving the frontal and temporal neocortex, along with associated overwhelming neuronal loss and severe gliosis.

Discussion

Humor can be dissected as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.

These two patients had pathological humor or a compulsive need for joking from bifrontal dysfunction, most critically from involvement of the right frontal lobe. Both patients had bifrontal damage, suggesting that both right and left frontal involvement is necessary for pathological humor. In the first case, bifrontal damage followed a stroke in the head of the left caudate nucleus, an area that mediates the frontosubcortical tracts, in a patient with previous compulsive behavior associated with right frontal encephalomalacia. The other patient had bvFTD with frontotemporal Pick’s disease that was greater on the right than left side on the neuropathology examination. Both patients had a compulsive tendency for disinhibited jokes to the point of disturbing their families and others. On examination, both were able to detect jokes and identify them as funny, but they did not experience or feel others’ jokes as funny or amusing. In essence, their humor was entirely internally driven.

These patients’ compulsive needs to make inappropriate jokes and to act childishly are consistent with “Witzelsucht,” from the German words for joke (Witz) and addiction (Sucht), and “moria,” or inappropriate cheerfulness. In the late 1880s, Hermann Oppenheim

5 described an addiction to trivial, excessive, and often sarcastic joking among four patients with right frontal lobe tumors,

5 and Moritz Jastrowitz

6 described silly and excited behavior in a patient with a large right frontal tumor. At the time, neuropathological studies of patients with similar acquired changes in personality showed involvement of the orbitofrontal and mesial frontal regions bilaterally but particularly on the right.

13 More recent reports have also emphasized involvement of the right hemisphere with Witzelsucht.

14 The paradox of Witzelsucht and moria is that these patients are actually insensitive to humor not generated by themselves. Even when they recognize and understand a joke, they do not affectively respond with a sense of mirth or with laughter. In other words, they do not feel the punchline as humorously connected to the storyline, yet simple forms of humor that do not require integration of a punchline (e.g., slapstick and puns) may still be experienced as funny.

There are many neuropsychiatric causes of pathological humor or Witzelsucht. Frontal lesions, like those described in our two patients, may result from brain trauma and other neurodegenerative diseases as well as from focal lesions. Dementia, particularly if frontally predominant, can increase the production of humor as well as decrease the sense of humor. In particular, patients with bvFTD, especially if right predominant, may have a tendency toward Witzelsucht, moria, slapstick, scatological jokes, or compulsive punning, along with decreased comprehension of complex or unfamiliar humor.

8,9,15 There are also developmental or genetic causes for pathological humor, such as Angelman syndrome (the “happy puppet” syndrome), Williams syndrome, and Down’s syndrome. In autism, although there is deficient humor processing linked to social or socioemotional aspects of humor, there can be a prominently retained predilection for physical humor and slapstick.

On initial presentation, clinicians must distinguish pathological humor or Witzelsucht from pathological laughter or PBA.

2,3 PBA may result in episodic, paroxysmal laughing, crying, or a mixture, from release of the dorsal upper pons laughter-coordinating center by bilateral upper motor neuron disease from strokes, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, multisystem atrophy, or progressive supranuclear palsy.

2 PBA is distinguishable from pathological humor in that its laughter is triggered by trivial or minimal stimuli and is often excessive and incongruent with the underlying mood and the extent of the patient’s emotional experience. A related unilateral condition is “fou rire prodromique,” or unmotivated, inappropriate, uncontrollable hearty laughter as the first symptom of cerebral ischemia that affects the inhibitory neurons for laughter in the ventral pons, left internal capsule-thalamus, left basal ganglia, or left parahipppocampal gyrus. Finally, epilepsy and electrical stimulation can lead to gelastic seizures or brief, stereotyped (mechanical, unnatural) epileptic laughter, usually from the left hypothalamic hamartomas, hypothalamic extension of other tumors, or left frontal or temporal lobe foci.

16–18Understanding the origin and nature of humor facilitates understanding the origin of pathological humor. In observing the relaxed, open-mouth display in primates during rough-and-tumble play in chimpanzees, Darwin

19 suggested that a novel or incongruous experience that surprises but is not a real threat leads to humor. In a psychoanalytic elaboration of this idea, Sigmund Freud

20 suggested that humor is an attitude (defense) by which people refuse to suffer by emphasizing the invincibility of their egos to provocation or reality. It involves the superego in the moment of humor reassuring the ego that the world is not dangerous, an occasion to gain pleasure and reassert the pleasure principle. Several subsequent theories propose that humor is a “stress antagonist” able to enhance the immune, cardiovascular, and endocrine systems and decrease stress-induced cortisol levels

21–23; a signal detector of “false alarms” that communicates nonthreatening deviations from the rules or mistakes in reasoning

24,25; or a mechanism for social gain, promoting social exploration,

26,27 social superiority,

27 or even sexual selection of a mate.

26,28,29 All of these theories, however, lack a neurocognitive explanation.

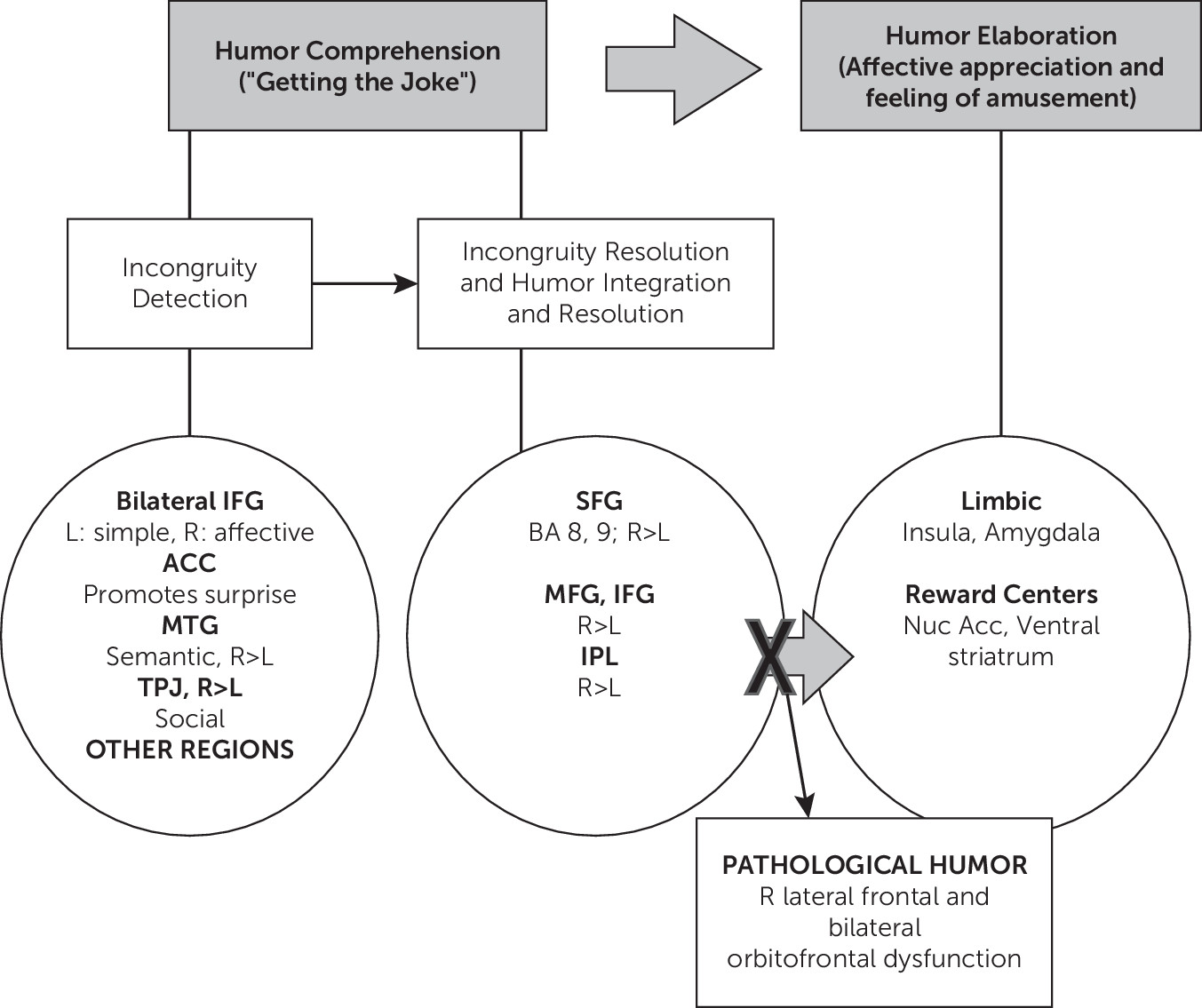

The most prominent neurocognitive theory of humor is the incongruity theory (

Figure 3), which begins with detection and resolution of conflicting alternatives in the frontal lobes followed by humor appreciation in pleasure/reward areas.

30–32 First, one must “get the joke” (humor comprehension), which involves detection of the incongruity of the punchline with the joke. The experience of surprise signals that the joke expectations are incongruent with the punchline. Surprise then precipitates a search for alternative explanations or incongruity resolution. The arrival at a new explanation is the trigger to humor elaboration or appreciation, the emotionally pleasurable responses that are experienced as amusement or laughter.

10,24,30,31,33Neuroscience and functional neuroimaging suggest that many brain regions can be involved in the incongruity theory of humor.

26,31,34,35 It is likely that both the left and right frontal lobes have a role in incongruity detection and incongruity resolution, with the left frontal lobe more responsive to simple humor and the right engaged with more externally generated, complex humor.

30,34 Simple humor engages the left frontal lobe (the inferior frontal gyri [IFG]), with input from the medial temporal gyri (MTG).

11,15,32,36 Examples of “simple humor” include the early detection of basic norm violations and plausibility, physical humor, slapstick, puns, familiar humor, and congruent but unfunny endings. Complicated humor, such as verbal semantic jokes requiring reconciliation with stored knowledge, also activates the right frontal and right MTG regions.

37,38 In addition, humor that specifically involves deviations from social expectations engages the left frontal lobe (the superior frontal gyri [SFG]) and the temporoparietal junction on the right,

26,35,39 part of the circuitry involved in taking another’s perspective, or Theory of Mind (ToM). Finally, investigators agree that all types of humor require the right frontal lobe, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and adjacent anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) for surprise when something is unexpected,

26,40 and the triggering of humor appreciation through frontal connections with limbic (insulae, amygdalae) and dopaminergic reward (nucleus accumbens, ventral striatum) areas.

26,30–32,37,41,42Although bifrontal injury is usually present, damage to the right frontal lobe appears critical for pathological humor. Patients with right frontal lesions remain sensitive to simple jokes, slapstick, or puns,

43,44 but they are impaired in appreciating externally generated, nonsimple, or novel jokes. They may not appreciate the relationship of their punchlines to their storylines and do not experience their funniness, preferring unfunny endings.

10,11,43–45 Hence, patients with right frontal lesions, like those with bvFTD,

15 are prone to simple, silly jokes.

46 These findings suggest that damage to the right dorsolateral/ventrolateral frontal lobe, possibly the SFG but also the medial frontal gyrus and IFG, impairs the integration of externally generated humor so that it can be experienced as funny.

35,36,45,47 In patients with the joking disease, concomitant disinhibition from orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) damage

48 permits self-generated and disinhibited jokes, rather than externally generated humor, to be the main trigger of limbic and reward areas for humor appreciation, implying a self versus other referential network for humor, as in ToM. Moreover, these patients appear compulsively driven to make jokes, suggesting additional damage to frontal (OFC-ACC)–striatal circuits involved in inhibitory control.

49There are no evidence-based pharmacological treatments for pathological humor, but published data on the treatment of disinhibition in different psychiatric and neurological conditions may apply to the treatment of patients with Witzelsucht. The first medications to try are the SSRIs, which were unsuccessful in decreasing pathological humor in these two patients, followed by psychoactive antiseizure medications such as valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. The use of dextromethorphan/quinidine, a combination indicated for pathological laughter, may reduce the amount of laughter without altering the need for humor, as was the case with our first patient. Finally, when these medications fail and further treatment trials are indicated, clinicians may resort to low-dose atypical antipsychotics to relieve the effects of pathological humor.

50We conclude that pathological humor is a compulsion for disinhibited humor. In our first patient, the compulsive drive developed after the initial right frontal lesion, but the focus of his compulsions on disinhibited jokes did not occur until after OFC-subcortical tract dysfunction from his left caudate stroke. Both patients had decreased appreciation of externally generated jokes associated with right lateral frontal dysfunction and a compulsive drive for disinhibited, self-generated joking and humor associated with OFC disease.

51,52 Future research can further clarify the mechanism and suggest management of Witzelsucht and moria in neuropsychiatric disease.