For more than a century, traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been associated with changes in psychological functioning, beginning with case reports of traumatic “insanity” and igniting a surge of interest in the role of the brain in personality, behavior, and emotions and the development of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. TBI results in diffuse brain injury, particularly to frontotemporal regions. It causes cognitive, behavioral, and personality changes that in turn can have a major impact on independence, work, study, leisure, and social and personal relationships. Because of the impact of TBI on frontolimbic structures, there is potential for development of organically based psychiatric disorders. Moreover, the experience of disability can have serious psychological consequences. The way a person responds to these impacts will be influenced by the circumstances, severity, and location of the injury, the person’s developmental stage, and preinjury psychosocial adjustment as well as postinjury supports. Psychiatric disorders occur commonly after TBI. We outline the epidemiology and natural history of psychiatric disorders after TBI.

Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disorders in the General Population

In the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication (N=5,692), 26.2% of respondents received a psychiatric diagnosis over a 12-month period, and 11.8% received multiple diagnoses. Rates of lifetime disorder were 46.7%, with 40.0% having more than one disorder.

1,2 Similar rates were obtained in an Australian study, with 20% of respondents meeting

ICD-10 criteria for a psychiatric disorder in the previous 12 months and 8.2% having more than one disorder.

3 Almost one-half (45.5%) had a lifetime history of psychiatric disorder. Across all age groups, females had higher rates of 12-month disorders (22%) than males (18%), and rates of disorders declined with age.

Methodological Issues in Studies of Psychiatric Disorders After TBI

The reported frequencies of psychiatric disorder after TBI vary considerably, from 18.3% to 83.3% in the months and years postinjury.

4,5 This variability is influenced by methods of study recruitment, diagnosis, injury severity, and time postinjury; some studies have made diagnoses in cases up to a decade or more postinjury, relying on retrospective recall of symptoms over many years.

There is variability in the measures used, with some studies using diagnoses documented in medical files and others using gold standard structured clinical interviews. In addition, there are significant challenges in classifying neuropsychiatric symptoms after TBI. Symptoms commonly associated with TBI, including fatigue, sleep disturbance, irritability, psychomotor slowness, reduced concentration and memory, apathy, and emotional labiality, are also characteristic of many psychiatric disorders. Standard classification systems (i.e.,

DSM-IV-TR) employed in TBI psychiatric research do not adequately address the complex neuropsychiatric features of TBI when considering differential diagnoses, specifying only that symptoms of idiopathic psychiatric disorders must not be better explained by a general medical condition.

6 Thus, potential for misdiagnosis is high.

Most prospective studies have been conducted over only the first year postinjury. Many have predominantly included patients with mild TBI. The vast majority have focused on depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Other studies have examined a range of diagnoses, but many have done so cross-sectionally or retrospectively.

Preinjury Psychiatric Disorders

There is some evidence to suggest that individuals with TBI have higher than expected rates of preinjury disorder,

7,8 whereas other findings suggest that rates are generally comparable to the general population.

9–11 Variability in comparison groups may partially account for this, because the TBI population differs from the general population in certain demographic aspects such as age and gender. Individuals with TBI are more likely to have preinjury alcohol use disorder

10 (

Table 1). Alway et al.

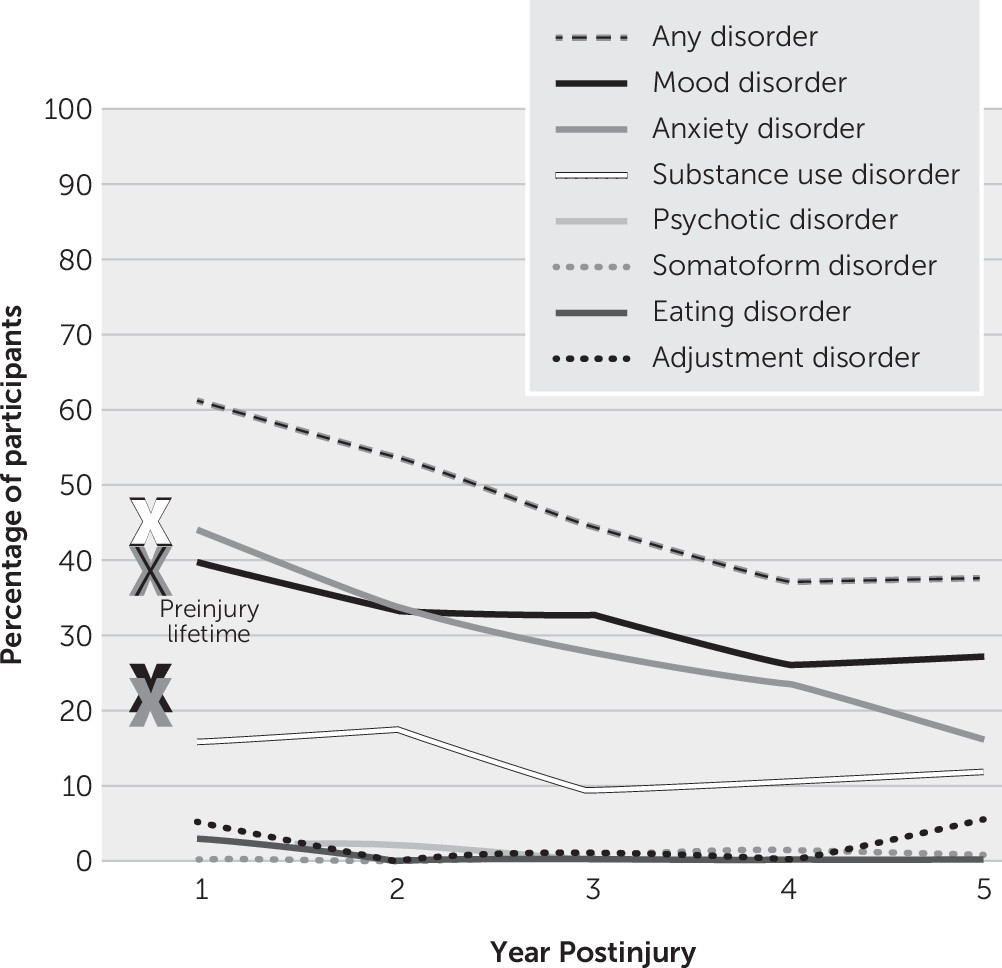

9 found that substance use was the most common preinjury diagnostic class, with 38.5% meeting criteria for alcohol or drug use disorder, which may reflect the relationship between alcohol, risk taking, and injury. Rates of preinjury mood and anxiety disorders were 23.0% and 21.7%, respectively. Preinjury psychotic (4.3%), eating (3.7%), somatoform (0%), and adjustment (9.3%) disorders were relatively rare.

Post-TBI Psychiatric Disorders

Most studies report that rates of psychiatric disorders after TBI are higher than those of the general population, and higher than rates prior to injury

9–11,17 (

Table 1). Studies report elevated frequencies of mood and anxiety disorders that increase throughout the first year postinjury, high comorbidity between disorders, and evidence for different patterns of onset by disorder type.

4,9–11,18–20 For example, compared with mood disorders, anxiety disorders appear to emerge earlier postinjury.

10 Rates of psychotic, somatoform, eating, and adjustment disorders appear comparable to those of the general population.

9,10 Postinjury diagnoses differ from those received prior to injury, with a decrease in diagnosis of substance use and an increase in diagnoses of mood and anxiety disorders.

9,10,17,19Results from medical file reviews vary widely, illustrating the limitations of this approach, in which diagnosis depends on cases presenting to services and on diagnostic methods. In a file review of health plan members in the United States with mild (N=803) or moderate to severe (N=136) TBI, reported rates of psychiatric disorders were 34.0% for mild and 49.1% for moderate to severe TBI respectively during the first year postinjury, 30.2% and 33.0% in the second, and 27.9% and 26.3% in the third.

21 These figures suggest a decline in disorders over time among those with moderate to severe TBI but not mild TBI.

Smaller file reviews from Denmark

22 and New Zealand

23 found much lower rates of 4.0% and 9.3%, respectively. Studies examining postinjury psychiatric disorders retrospectively have reported rates ranging from 48.3% to 83.3%,

5,17,24,25 implying that psychiatric disorders may continue to emerge after the first year postinjury.

Prospective studies examining a range of psychiatric disorders using structured clinical interviews, mostly limited to the first year postinjury, have reported disorder rates ranging from 18.3% to 60.8% in the first year postinjury. In studies estimating point prevalence, lower rates have been reported in samples with predominantly mild TBI

4,18 compared with studies including a greater range of diagnoses and injury severity.

10,11 Only one study, by Alway et al.,

9 has examined the full spectrum of disorders prospectively over 5 years postinjury. In their sample of predominantly moderate to severe cases of TBI, overlapping with the data set of Gould et al.,

10 74.5% received a psychiatric diagnosis over the 5 years, commonly emerging within the first year (77.7%). Anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders were the most common diagnostic classes, often presenting comorbidly, and 56.5% experienced a novel diagnostic class not present prior to injury. Disorder frequency ranged between 61.8% and 35.6% over time, with disorder likelihood decreasing by 27.0% with each year postinjury.

Mood Disorders and TBI

Mood disorders are the most common psychiatric disorder after sustaining a TBI, presenting at rates higher than in the general population.

4,10,19,20,26 Mood disorders frequently develop without a preinjury psychiatric history

9–11,18,20,27 and present comorbidly with anxiety disorders in approximately three in four cases.

10,18,20Reported rates of bipolar-type disorders have been relatively low, ranging from 2% to 9% in the first year postinjury.

10,11,19,28 Major depressive disorders are the most common diagnosis. Prospective studies with predominantly mild TBI samples report fairly consistent point prevalence rates, ranging from 17.0% to 23.1% at 3 months,

18,28,29 18.5%−23.2% at 6 months,

28,30 and 13.9%−18.6% at 12 months

4,18,28 postinjury.

Results of prospective studies examining the entire first year postinjury and a greater range of injury severity are more variable, with rates ranging from 11.3% to 42.4% for major depressive disorder,

10,11,19,20,27,28 1.0% for dysthymia,

10 and 5.3%−19.6% for depression not otherwise specified.

10,11 Among studies examining rates of major depressive disorder at multiple time points within the first year, the timing of onset and course of disorder have been variable. Studies involving predominantly mild TBI cases suggest that major depressive disorder onset occurs within 3 months following injury,

20,27,28 whereas a more recent study focusing on moderate to severe injuries reported that onset is more common 6–12 months postinjury.

10 These findings suggest that those with more severe injuries may show more delayed onset of symptoms. In their 5-year prospective study of individuals with moderate to severe TBI, Alway et al.

9 found that rates of mood disorders were highest in the first year (40%) postinjury but remained significantly elevated over population rates at 27.7% in the fifth year postinjury. Major depressive disorder was the most common diagnosis, presenting at rates between four and six times (18.7%−28.3%) those in the general population (4.2%) over the 5-year period. A subsyndromal variant of major depressive disorder, diagnosed as depressive disorder not otherwise specified, was the next common mood disorder (6.5%−15.8%), while dysthymia (0.0%−2.0%) and bipolar disorder (0.0%−3.1%) were relatively rare. Reported rates of depressive disorders from studies with retrospective or cross-sectional designs vary from 12.1% to 61.1% for major depressive disorder, 0%−14% for dysthymia, and 0.0%−16.7% for bipolar-type disorders.

5,7,17,24,25,31 Findings generally indicate poor disorder resolution,

17,24,31 although others have found decreasing

7 and stable

24 rates of predominantly major depressive disorder with greater time postinjury.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

OCD is relatively uncommon in the general population, and most findings suggest it remains so after TBI. Three prospective studies have reported low rates of OCD within the first 12 months post-TBI: 4%

18 and 1.2%

4 in mild samples and 1%

10 in moderate–severe samples. Alway et al.

9 reported low frequencies of OCD (0.0%−2.6%) that were maintained over the first 5 years postinjury. Most retrospective studies have found similarly low rates of OCD.

5,17,25 The exception is the retrospective study of Hibbard et al.,

24 in which 15% were diagnosed as having OCD, according to the

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, an average of 8 years postinjury. One possible explanation for such a discrepancy is that TBI-related behaviors (e.g., checking due to memory problems) could be misattributed as symptoms of OCD, artificially inflating rates of diagnosis.

Eating Disorders and TBI

The limited studies to date indicate that postinjury eating disorders present at rates comparable to those in the general population, commonly in the context of a preinjury history. In Gould and colleagues,

10 prospective study, 4.9% had had an eating disorder prior to injury, with 2.9% experiencing a continuation or recurrence of the disorder in the 12 months following injury. Extending this study, Alway et al.

9 found only one eating disorder case (0.7%) in the second year and no cases in years 3–5 postinjury. Similarly, in retrospective studies van Reekum et al.

5 reported one case (5.5%) of anorexia nervosa with preinjury onset, whereas Whelan-Goodinson et al.

17 found a preinjury rate of 2%, with 1% still satisfying diagnostic criteria following injury.

Factors Associated With Psychiatric Disorders After TBI

Understanding the risk factors associated with the development and course of psychiatric disorders after TBI may assist in prevention and/or identification of management strategies. Likely contributory factors include demographic or personal factors (i.e., genetic susceptibility and preinjury disorder), injury-related changes, and posttraumatic adaptive issues.

In regard to demographic factors, some studies have found that older age increases risk for anxiety

43,53,54 and mood disorders

27,28 and younger age increases risk for substance use disorders.

9,54 Alway et al.

9 found the likelihood of disorder increased with age up to 30 years and declined with age thereafter. This may explain why other studies have found no significant association of age with psychiatric disorder after TBI.

7,20,24 Female gender has been associated with increased risk of anxiety

7,24,53 and mood disorders

7,29,54 in some studies but not others.

4,9,11,25 Two studies found that male gender increased risk of postinjury substance use disorder.

7,9 Lower education has emerged as a risk factor for depression in some studies

4,54 but not others;

20,53 it does not appear to be associated with the development of postinjury anxiety disorders.

24,54 Lower education has also been associated with increased likelihood of substance use disorder.

9Although rates of postinjury psychiatric disorders appear elevated for all individuals, the presence of a preinjury psychiatric history is the strongest risk factor for postinjury psychiatric disorders in general and for each of the diagnostic categories of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

4,9,21,24,53 The timing of onset of postinjury disorders may also vary according to preinjury psychiatric status. Alway et al.

9 found that cases of postinjury disorder with a preinjury history were significantly more likely than novel cases to present in the first year postinjury (85.1% versus 59.5%). Nevertheless, Alway et al.

9 also showed that while individuals with a preinjury psychiatric history were significantly more likely to develop a postinjury disorder, two-thirds of these cases developed a diagnostic class not present prior to injury; 37.0% had preinjury diagnostic class only, 27.2% novel diagnostic class only, and 35.8% both a preinjury and novel diagnostic class. Furthermore, the majority without a psychiatric history also developed a disorder postinjury. Therefore, psychiatric presentations after TBI do not merely represent a continuation of preinjury disorders into the postinjury period.

9,10Even though rates of mood and certain anxiety disorders appear to be somewhat higher in moderate to severe TBI samples, previous studies have found no evidence to suggest that TBI severity influences risk for postinjury psychiatric disorders.

7,9,25,54 Although the presence and severity of bodily injury in general does not appear related to psychiatric disorders after TBI,

20,54 one previous study found that sustaining a limb injury increased risk of psychiatric disorder by 6.4 times at 12 months postinjury,

53 and this association was confirmed by Alway et al.

9 The reduced independence, pain, and longer periods of physical rehabilitation and hospitalization associated with sustaining a limb injury may increase distress, heightening vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. Therefore, individuals with limb injuries may require additional support to adjust to the impact of their injury. Time postinjury has also been identified as a predictive factor, with one study finding a 27% decrease in the likelihood of a psychiatric disorder with each year postinjury.

9 Several studies have shown the presence of psychiatric disorders to be associated with poor functional outcomes and lower quality of life.

45,55Conclusions

Individuals with TBI show significantly elevated rates of depressive and anxiety disorders, most commonly major depressive disorder and PTSD, which are most likely to emerge in the first year postinjury, although severe injury may be associated with more delayed onset. Although individuals with a preinjury history of psychiatric disorders are more likely to develop these disorders, the nature of the disorders may change after injury, and many individuals also develop novel psychiatric disorders. While the frequency of anxiety disorders diminishes, depressive disorders are more persistent postinjury. Substance use, while high before injury, declines after injury. Studies to date suggest that the frequency of psychotic, eating, somatoform, and adjustment disorders among persons with TBI do not exceed population rates.