Catalepsy, a trance-like state in which a fixed body posture is sustained for a prolonged period of time, has long been recognized as a sign of brain dysfunction attributable to psychiatric and/or neurological conditions. Catalepsy and other psychomotor symptoms were consolidated by Karl Kahlbaum under the term catatonia and played a formative role in early attempts at classification of mental disorders. Kahlbaum’s concept of catatonia as a distinct disease state that cycled through melancholia, mania, stupor, confusion, and eventually dementia, was influenced by his knowledge of the progressive course of syphilis ending in “general paralysis of the insane,” which was widely prevalent among asylum patients at that time. Four of the 26 catatonic case patients in his seminal 1874 monograph actually died with neurosyphilis.

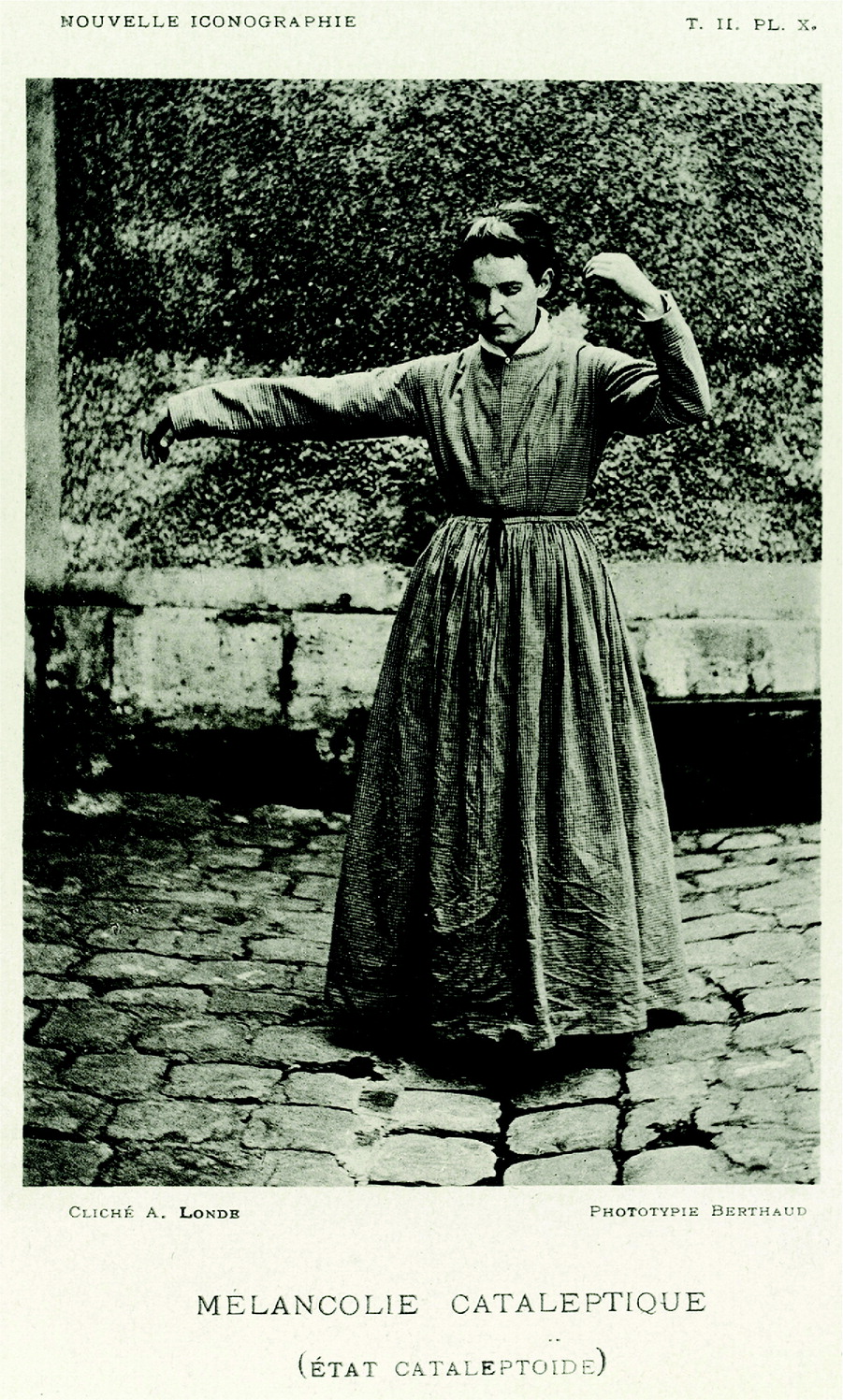

A unique example of catalepsy is the en garde or fencing posture in which the patient shows unilateral arm extension, flexion of the contralateral arm, and often head deviation toward the extended limb. Rarely reported today, this iconic posture was depicted in multiple genre paintings of asylum patients, which were popular throughout Europe in the 17th–19th centuries, suggesting that this expression of catalepsy was commonly known. The woman in the photograph was reported by Jules Seglas and P. Bezançon at the Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris in 1889. In contemporaneous notes, they described her as delusional and hallucinating, with episodes of sorrow, excitement, stupor, and catalepsy. They considered the diagnosis of catatonia formulated by Kahlbaum as a primary disorder but concluded instead that the patient had melancholia with associated catatonic features.

They also considered hysteria, which Jean-Martin Charcot was studying at the Pitié-Salpêtrière as a neurological disorder by inducing catalepsy under hypnosis. Charcot and colleagues also continued the tradition initiated by Philippe Pinel of studying patients by using illustrations and photographs. Charcot’s public depictions and demonstrations of catalepsy in women have been criticized as merely hypnotic suggestion or exploitive performances, raising the possibility that this photograph was staged. However, the notes in the case do not support hysterical posturing in its modern sense of a conversion disorder, as the patient was profoundly psychotic and depressed in addition to displaying spontaneous catatonic symptoms without hypnosis. The authors also claimed to have ruled out voluntary posturing using electromyography.

The fencing posture also has neuroanatomic implications. Like “frontal release signs,” it may represent disinhibition of a primitive reflex similar to the tonic neck reflex elicited in newborns due to brain immaturity or attributed to functional decerebration following acute concussive injuries. The fencing posture is also well known as a form of asymmetric tonic seizures useful in localizing an underlying lesion in the supplementary motor area contralateral to the extended arm. Focal seizures can result from cerebral syphilitic infiltration or gummas, which may affect the supplementary motor area, such that the widespread recognition of the fencing posture in past centuries may be explained by tonic seizures observed in asylum patients with neurosyphilis.

This image of the fencing posture should serve as a reminder that catalepsy is a nonspecific catatonic sign that may provide clues to underlying disorders and serve as a localizing behavioral sign of neuroanatomic pathology.