CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old right-handed woman with a history of chronic headaches presented with 2 months of continuous auditory hallucinations. The hallucinations began as a distant and indistinct version of her own voice inside her head. They progressed to become the fully formed speech of a man and a woman (and occasionally others) in constant conversation at all hours of the day. These voices usually seemed to emanate from a location outside the patient’s head, mostly from her left, and they varied in apparent loudness and distance. The voices were admonishing (e.g., for buying cigarettes), accusatory (e.g., accusing her of checking her husband’s cell phone for contact with other women), menacing (e.g., “we will be happy when you die”), and mocking (e.g., for “not talking back”). Watching television, listening to music, and conversing with others dampened the voices. They interfered with her sleep significantly. While at no point did she think the hallucinations were real, they worsened to the point that she was constantly distressed and was responding to them in front of her family.

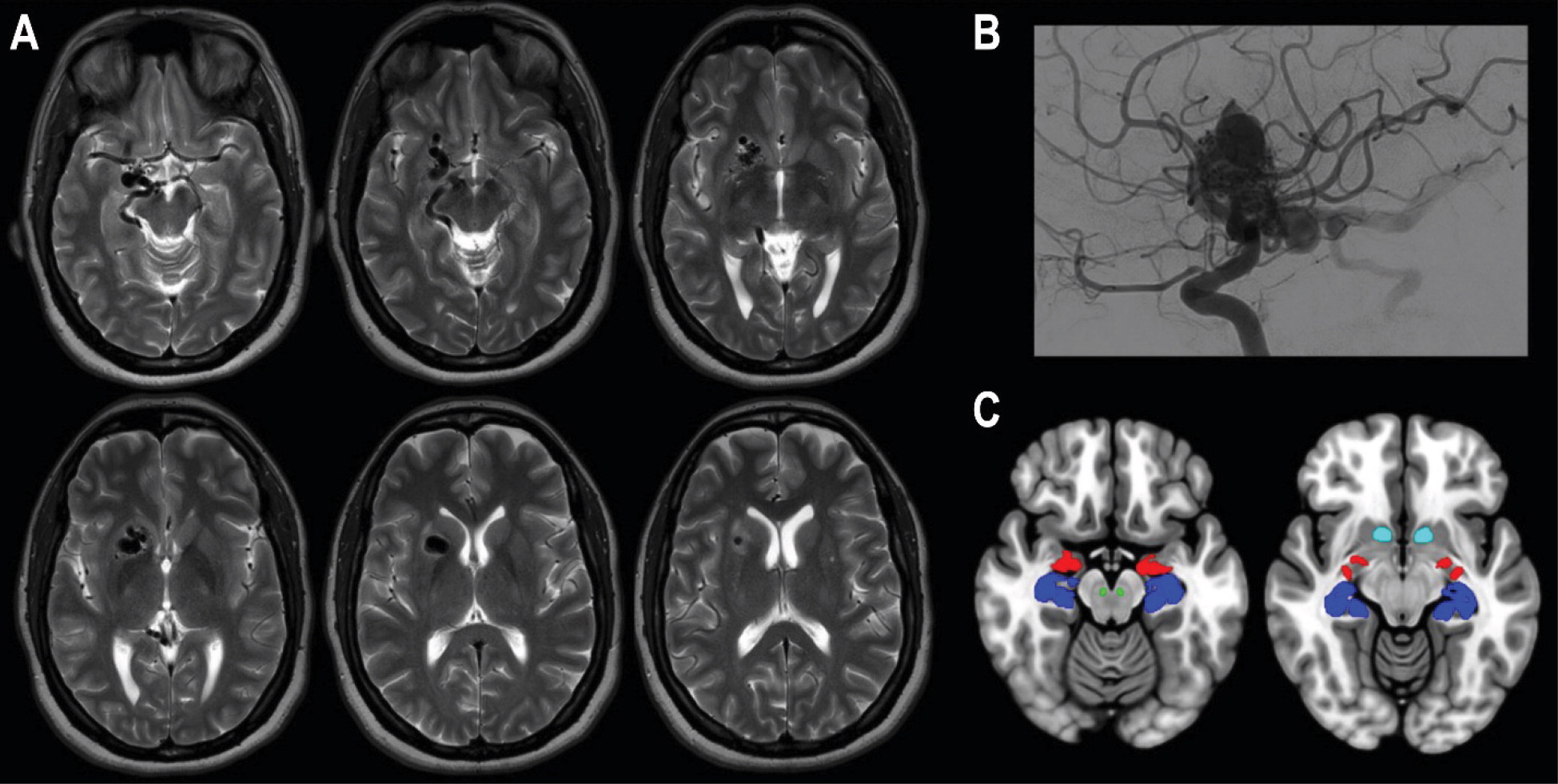

At the time of onset, the patient had been taking buprenorphine for opioid use disorder and zolpidem for insomnia. When the auditory hallucinations began, her primary care physician discontinued both medications. When the hallucinations did not abate, she was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. A neurologic examination was unremarkable, except for mildly decreased sensation to light touch and pinprick on the left side (the face and leg, sparing the arm). On mental status examination, there was no evidence of delusions, a thought disorder, behavioral abnormalities, or significant negative symptoms. Diagnostic workup revealed a right-hemisphere AVM (

Figure 1), which was de novo; a brain MRI 12 years earlier was normal. At that time, the patient had been experiencing chronic headaches, which had progressed over the ensuing years and eventually led to opioid overuse. In addition, a remarkable family history was elicited: the patient’s daughter had posterior fossa anomalies, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac anomalies, and eye anomalies (PHACE) syndrome, a genetic disorder involving posterior fossa brain malformations and cerebral vascular abnormalities (

2), and her son was diagnosed with psychosis related to a neurodevelopmental disorder in his late teens.

A comprehensive diagnostic workup for hallucinations in the setting of the AVM was pursued. It included a continuous 24-hour EEG performed while the patient was reporting auditory hallucinations (results were normal, with no periodic patterns, seizures, epileptiform discharges, or focal abnormalities), an infectious workup (HIV and syphilis tests were negative), a metabolic workup (thyroid studies were normal), urine toxicology (negative results), and an autoimmune workup (paraneoplastic and limbic encephalitis serum panels were normal). The patient was loaded on valproic acid, continued at 500 mg twice daily, to treat possible seizure-related psychosis (ictal, postictal, or interictal). She initially said that the voices seemed more distant; however, they persisted despite a therapeutic level of valproic acid. She reported that the voices said, “We’re not going anywhere.” After 2 weeks, phenytoin was loaded and continued at 300 mg daily, which had no significant effect at a therapeutic level. The patient reported an initial slight improvement of the auditory hallucinations with the initiation of olanzapine (10 mg daily); however, the hallucinations did not clearly sustain a change in frequency, intensity, or quality over time. Her medication was switched to aripiprazole, titrated up to 20 mg daily, with the same reports of only slight relief of symptoms, if any at all. Notably, during her hospitalization, lorazepam (2 mg) had been given prior to an MRI; it caused the voices to sound like they were at a lively party, distressing the patient. Later, there was a similar intensification of the hallucinations when she consumed an alcoholic beverage at her birthday party. After discharge, she resumed working full-time despite ongoing distress due to the hallucinations.

The only complete relief the patient experienced was during a 48-hour period in which she had a high fever due to tonsillitis. The voices said, “We will give you a break because we are sick too,” and then the voices disappeared. During these 2 days, the auditory hallucinations abated completely, but they returned to their previous state later. Environmental noises, such as television, continued to provide relief, and the patient spent hours watching television with the volume turned up high. At other times, however, environmental noises such as running water seemed to serve as a source of the hallucinations. The AVM was deemed not amenable to endovascular or open-neurosurgical procedures, and the patient was referred for stereotactic radiosurgery.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this report is the first of an AVM producing auditory hallucinations. The study of auditory hallucinations with a likely etiology can help to uncover the pathophysiology of hallucinations in primary psychotic disorders (

1). This case sheds light on the current neuroanatomic, neurochemical, phenomenological, and genetic models of the pathogenesis of auditory hallucinations in primary psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia.

With regard to neuroanatomic models of auditory hallucinations, this case aligns well with decades of work implicating disease of the medial temporal lobe (

3–

5). These archetypal disorders include not only temporal lobe epilepsy and autoimmune encephalitis but also space-occupying lesions, as up to 20% of temporal lobe tumors may produce symptoms associated with psychosis (

1,

6). Ictal, postictal, or interictal psychosis are unlikely explanations for our patient’s continuous experience of hearing voices; EEG detected no epileptiform activity, symptoms continued despite therapeutic levels of two anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines and ethanol worsened the hallucinations (

7). Moreover, ictal or postictal psychosis is almost always associated with other mental status changes, such as confusion or alterations of awareness; our patient’s high level of social and occupational functioning was not consistent with continuous seizures for a period of months. Although interictal psychosis does present with fewer negative symptoms and greater patient insight into positive symptoms than schizophrenia—our patient had insight into her hallucinatory experiences and lacked negative symptoms—it would only be expected in a patient with a long history of uncontrolled seizures (

8). Therefore, the AVM may have induced auditory hallucinations not through epileptic activity but rather by generating pathological neurochemical transmission involving the medial temporal lobe.

Imaging showed the AVM distorting the entirety of the patient’s mesolimbic pathway (

Figure 1), the neurochemical system considered to be fundamental in the generation of positive symptoms in schizophrenia (

4). Thus, it is possible that aberrant function of the medial temporal lobe and mesolimbic pathway from structural reorganization or metabolic disruption from a blood flow “steal” phenomenon induced by the AVM are directly related to this patient’s hallucinations (

9,

10). The remarkable 48 hours of fever that completely abated the hallucinations is worth noting with regard to neurochemical models of schizophrenia. The episode is reminiscent of fever treatment for psychosis (using malaria infection) in the early part of the 20th century, which was demonstrated to cure up to 25% of those treated (

11). The present case serves as a reminder that tantalizing clues to therapeutics may lie in yet-to-be-identified aspects of fever, which appears to alter the neurochemical milieu of pathways relevant to auditory hallucinations.

Clinical cases and neurobiological models mutually inform each other, and this case of an AVM associated with auditory hallucinations supports certain models for the pathogenesis of auditory hallucinations. It reinforces the importance of the medial temporal lobe, a structure involved in verbal memory. Experiencing auditory verbal hallucinations is associated with increased activity in the medial temporal lobe bilaterally (

12). Activation of the microcircuitry of the right or left medial temporal lobe through direct stimulation has long been known to produce auditory hallucinations (

13). Antibodies against cell-surface proteins of the medial temporal lobe produce hallucinations in up to 43% of patients with

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis (

14). In contrast to the established lateralization of language to the dominant hemisphere, focal pathology (mass lesion or autoantibodies) or electrical activity (seizure or applied directly) of either the dominant or nondominant temporal lobe can generate hallucinations of language or speech (

5,

6,

15).

In our patient, the lateral portions of the temporal lobe, including the primary auditory cortex and auditory association cortex, were structurally and hemodynamically undisturbed by the AVM. Only the medial temporal lobe (the amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus) were affected. Based on this case, we would caution against theoretical and functional neuroimaging models of auditory hallucinations that assert the primacy of the auditory cortex; these models must account for the involvement of the medial temporal lobe. This concept is consistent with the model established by Gloor (

15): the distributed neuronal networks of both the medial and the lateral temporal lobes can, when activated, recreate the totality of a given perceptual and affective first-person experience (

16).

Several phenomenological aspects of our patient’s hallucinatory experiences are notable. Her hallucinations had features in common with those seen in schizophrenia. They were composed of multiple voices commenting on her, Schneider’s first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia (

17), which have only rarely been reported in auditory hallucinations associated with focal lesions. Additionally, the spatial quality of the hallucinations—emanating from outside the head, often to the left of space, and from objects in the environment (e.g., from running water)—suggests some relationship to the lateralized function of the right hippocampus for spatial information (

18). These spatial characteristics have also been reported in schizophrenia (

19). However, although the patient’s hallucinations were indistinguishable in intensity and quality from auditory hallucinations experienced as a positive symptom of schizophrenia, she did not meet criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (

20). It is fascinating that patients, such as the one described in this case, who do not meet the criteria for schizophrenia—because they have insight into their experiences and do not show functional impairment—do not appear to have the striatal dopaminergic dysfunction associated with auditory hallucinations in patients with psychotic disorders, although the two groups manifest the same cortical abnormalities (

21).

Finally, there are remarkable genetic aspects of this case. The first-degree relative with PHACE syndrome points to a possible hereditary vulnerability to the development of AVMs. The first-degree relative with a history of psychosis may confer susceptibility to the development of auditory hallucinations, as has been demonstrated in patients with a family history of psychosis presenting with these hallucinations following a head injury (

22).

In summary, this case is an example of how lesions producing hallucinatory experiences can generate hypotheses and support or challenge existing models for them (

23–

25).