Given the public health burden of stroke in the United States (

1), it is critical to identify modifiable risk factors to lessen overall stroke incidence and improve stroke outcomes. Multiple research studies (

2–

4) and meta-analyses (

5,

6) suggest that depression is among the key risk factors for stroke and that about one-third of stroke patients receive this diagnosis (

7). Preexisting depression, which was estimated to affect more than 10% of study participants included in a meta-analysis (

8), has been less investigated, and its association with stroke outcomes remains poorly understood.

Depression can increase the incidence of stroke, stroke severity, and mortality (

2–

5). This increased risk suggests that depressive symptoms may be a marker of subclinical vascular disease, even among people without prior stroke or heart disease (

9). The association between depression and stroke risk may be mediated by traditional stroke risk factors (e.g., diabetes and hypertension) but also, perhaps, by certain demographic variables (

9). To assess the association between depression and stroke outcomes, traditional risk factors can be evaluated among individuals with and without depression.

To date, most research investigating depression and stroke has not included comparisons across racial-ethnic minority groups (

5,

6,

10). Reasons for such sample selection may include differences in behavioral and social responses and disparities in access to health care (

11). In fact, few studies in the United States have focused specifically on the Hispanic population (

11,

12), yet it has been shown that Hispanic persons may have a higher burden of cerebrovascular disease than non-Hispanic White persons (

12).

Florida is home to a population comprising 26% Hispanic or Latino persons (

13), and the incidence of stroke is increased in some subdemographic populations compared with non-Hispanic White populations (

14,

15). In a survey of Florida adults conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 17% of respondents reported having been told by a health care professional that they have a depressive disorder (

16). With regard to race and ethnicity, 19% of non-Hispanic White adults and 15% of Hispanic adults reported having a depressive disorder (

16). However, in a large study of Hispanic adults, 27% of participants reported high levels of depressive symptoms; the proportion was even higher in certain demographic subpopulations (

17). Because Hispanic persons seem to have a higher burden of cerebrovascular disease and possibly depressive symptoms compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts, it is imperative to explore the relationship between race-ethnicity, preexisting depression, and stroke outcomes, such as ambulatory status.

We analyzed data from the large, ethnically diverse Florida–Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities (FL-PR CReSD) registry to examine the association of preexisting depression with poststroke ambulation (independent or dependent ambulation) at hospital discharge and whether sex or race-ethnicity altered this association.

Methods

The FL-PR CReSD registry was a voluntary registry that included data from Get With the Guidelines–Stroke (GWTG-S) participating hospitals in Florida and Puerto Rico from 2010 to 2017 (

18). The goal of the registry was to create highly effective, culturally tailored interventions for delivering stroke care (

19,

20). Deidentified data on hospitalized participants with a final diagnosis of any stroke type were included in the registry (

18–

20). Race and ethnicity categories have been previously described (

19). The present study was a secondary analysis of registry data approved by the institutional review board at the University of Miami with a waiver of informed consent.

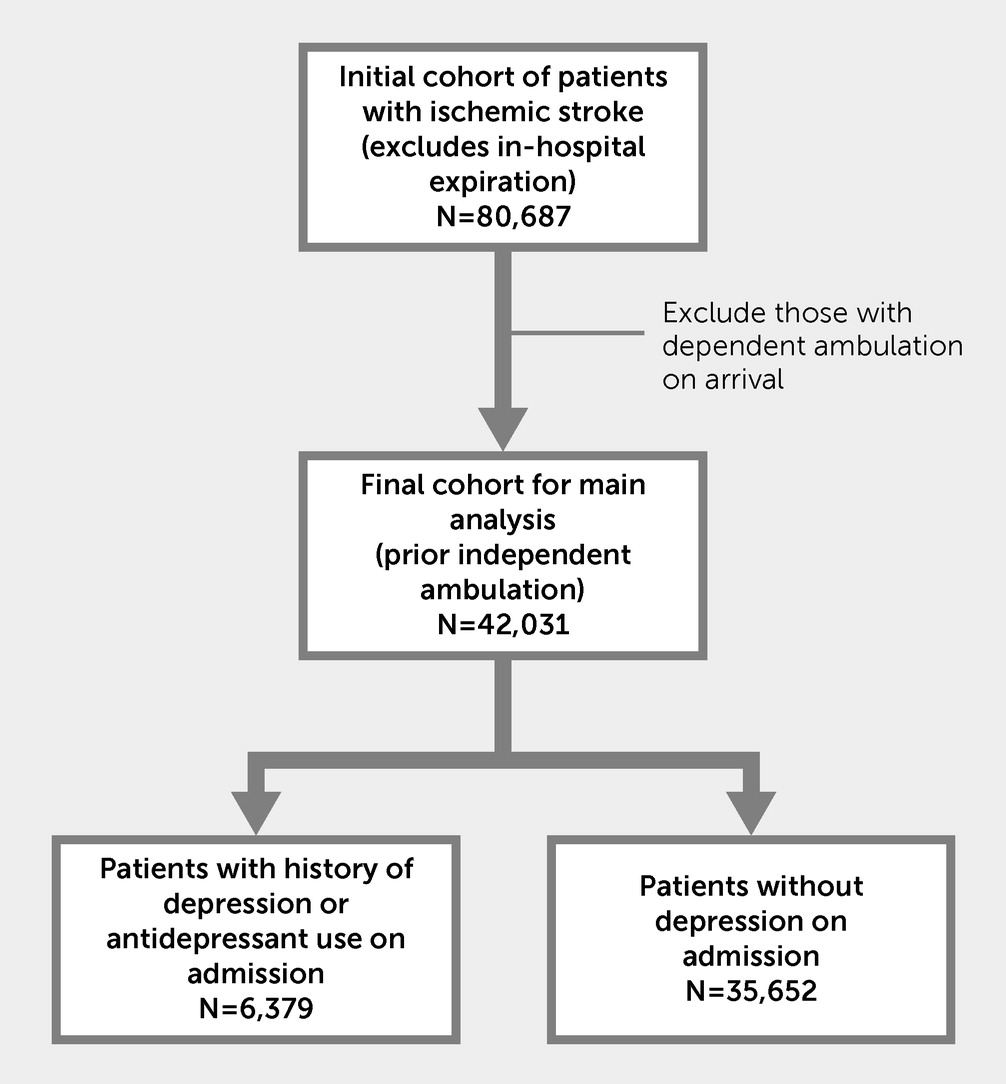

Data from a total of 80,687 ischemic stroke participants discharged from 84 institutions from January 2014 to December 2017 were considered (excluding in-hospital expiration). Of these participants, 42,031 were independently ambulatory before their stroke and included for analysis. Preexisting depression was identified by history or use of antidepressant medications upon hospital admission (

21). A total of 6,379 participants with depression (15%) were identified in this manner (

Figure 1).

Univariate analyses (t test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables) of participant characteristics (age, race-ethnicity, and insurance status) and previous medical history (prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, tobacco smoking, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, carotid stenosis, coronary artery disease, and chronic renal insufficiency) were performed, and data on mode of hospital arrival, time from symptom onset to arrival, initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and thrombolytic treatment were collected. The association between preexisting depression and race-ethnicity and sex with independent ambulation at hospital discharge was assessed by conducting multivariable analyses and adjusting the aforementioned covariates. Generalized estimating equations accounted for clustering effects within each hospital. To reduce multicollinearity among correlated factors, stepwise logistic regression was run to select independent factors deemed clinically relevant and statistically significant. Tobacco smoking, dyslipidemia, carotid stenosis, and coronary artery disease were highly correlated with other factors and removed from the final model (for the full model, see Table S1 in the online supplement). Final models were adjusted for participant characteristics (age, sex, race-ethnicity, and insurance status), previous medical history (prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and chronic renal insufficiency), mode of hospital arrival, time from symptom onset to arrival, prestroke ambulatory status, initial NIHSS score, and thrombolytic treatment; results are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Interactions between preexisting depression and race-ethnicity or sex were evaluated.

The primary analysis was repeated twice: defining the exposure of depression based on medical history only, regardless of antidepressant use, and defining it based on a history of depression with antidepressant use (for further details, see Tables S2 and S3, respectively, and the supplemental Results section in the online supplement).

Most variables had missing values in fewer than 5% of cases, except for insurance status (8%) and discharge ambulatory status (6%). Statistical analyses with a complete-case approach were completed by using SAS (version 9.4).

Results

Analysis of the 42,031 participants with independent ambulation before ischemic stroke revealed that 6,379 participants (15%) had preexisting depression. The mean±SD age of all participants was 70.4±14.2 years. A total of 22,028 (52%) participants were male, 27,129 (65%) were White adults living in Florida, 6,902 (16%) were Black adults living in Florida, 5,802 (12%) were Hispanic adults living in Florida, and 2,918 (7%) were Hispanic adults living in Puerto Rico. Demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics stratified by preexisting depression status are summarized in

Table 1. Univariate analyses revealed that participants with depression were more likely than those without depression to be women (60% vs. 45%, p<0.001), to be White adults living in Florida (76% vs. 63%, p<0.001), to have arrived at the hospital via emergency medical services (63% vs. 60%, p<0.001), and to have vascular risk factors across all comorbid conditions examined (all p values <0.001).

At discharge, 23,399 of 42,031 participants (56%) were independently ambulatory. Participants with depression were less likely than those without depression to have independent ambulation (52% vs. 56%, p<0.001).

In the final model, preexisting depression decreased the likelihood of achieving independent ambulation (odds ratio=0.88, 95% CI=0.81, 0.97) (

Table 2). In addition, a lower probability of independent ambulation was associated with female sex; Black race-ethnicity; older age; Medicare insurance; and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, and chronic renal insufficiency. In contrast, a higher likelihood of independent ambulation was associated with hospital arrival by emergency medical services, arrival within 4.5 hours of stroke symptom onset, an initial NIHSS score <5, and thrombolytic therapy. No interactions were found between preexisting depression and race-ethnicity or sex.

Discussion

In a large, ethnically diverse registry of people experiencing acute ischemic stroke, preexisting depression was shown to be a significant predictor of worse poststroke ambulation at hospital discharge, irrespective of differences in age, race-ethnicity, vascular risk factors, prior stroke, and initial stroke severity.

We found a significant association between both being female and being non-Hispanic White and an increased likelihood of preexisting depression, but we did not observe an increased likelihood among participants in other racial-ethnic groups. Moreover, preexisting depression did not alter the effects of sex or race-ethnicity on hospital discharge ambulatory status and remained an independent predictor of dependent ambulation. These results remained similar whether our exposure variable was medical history with or without antidepressant use (

Table 2) or medical history only, regardless of antidepressant use (see Table S2 in the

online supplement). Furthermore, when the analysis was restricted to only participants with a previous medical history of depression, prior use of antidepressant medication was not associated with hospital discharge ambulatory status (see Table S3 in the

online supplement).

Our findings contrast with those of previous studies that showed increased prevalence of depression before stroke (

11,

15) and before myocardial infarction (

22) among Hispanic participants compared with non-Hispanic White participants. This discrepancy is likely multifactorial. First, the Hispanic population in our study predominantly comprised people with Caribbean and Latin American heritage residing in Florida or Puerto Rico and hence represents a different subpopulation than that found in studies that included participants of predominantly Mexican-American (

15,

22) or nondocumented origin (

11). Second, our study had a more robust sample size: our sample comprising 15,927 Hispanic participants is six to 10 times larger than that of previous studies with the number of Hispanic participants ranging from 151 to 2,211 (

11,

15,

22). Nevertheless, the overall proportion of Hispanic ethnicity represented in our study was somewhat lower (19%) than the estimated proportion in Florida (26%), even with the inclusion of Hispanic participants from Puerto Rico (

13).

Vascular risk factors were more frequent among participants who had depression than among those who did not. These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that late-life depression may be a subclinical marker of vascular disease, resulting in increased incidence of stroke (

11). The exact pathophysiology behind this association remains elusive but perhaps is explained by the increased incidence of vascular disease among participants with depression (

11), which sometimes manifests with unhealthy lifestyle and behaviors, such as tobacco smoking (

23), low physical activity (

24), obesity (

25), and overeating (

26), all of which contribute to development of vascular disease. Evidence suggests that people with depression may have lower adherence to medication, which may further augment stroke risk. Multiple other mechanisms linking depression with vascular disease have been postulated, such as elevated systemic inflammation and inflammatory markers (

27), increased incidence of cardiac arrhythmias (

28), and platelet reactivity (

29). Regardless of the exact mechanism, in our study, preexisting depression remained an independent predictor of dependent ambulation even after accounting for baseline differences in vascular risk factors.

Recently, Ford et al. (

30) reported an analysis from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study, a large national, longitudinal study of stroke in the southeastern United States. In an analysis of 1,262 incident strokes among more than 24,000 White and Black participants, the investigators found that compared with participants without depressive symptoms, those with mild depressive symptoms assessed on the 4-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale had a 39% increased risk of stroke and those with more severe depressive symptoms had a 54% increased risk, regardless of race (

30). In their findings from the community-based Guizhou Population Health Cohort Study, which included more than 7,000 individuals, Yu and colleagues (

31) reported that those with greater depressive symptoms on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire had a 12% increased risk of stroke. These findings, taken together with those of the present study, indicate that depression can not only increase the risk of stroke but also independently modify stroke outcomes, such as ambulation, among diverse groups of individuals. Therefore, these findings are clinically relevant and have public health implications in primary stroke prevention and for improvement in short-term outcomes, such as ambulation, among those who experience a stroke.

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the FL-PR CReSD registry, which uses data in the GWTG-S registry from participating hospitals. GWTG-S does not clearly identify participants who have depression. Therefore, some participants with depression, particularly mild depression, may not have been identified, as evidenced by a depression rate of 13% in our sample compared with a rate of 17% among Florida adults (

16). This limitation is likely the result of identifying depression on the basis of documented medical history of depression or antidepressant medication use on hospital admission; however, the specific antidepressant medication is not documented in the GWTG-S registry. Therefore, identification of depression could have been skewed because of overlapping indications for antidepressant use (e.g., anxiety, panic disorder, and migraine). To address this potential bias, our analysis based on history of depression regardless of antidepressant use as the exposure variable yielded similar results and strengthens our argument. Lastly, the willingness to report depression could vary by sex and race-ethnicity and potentially vary across demographic subgroups.

Conclusions

An inability to independently ambulate at hospital discharge was observed among stroke participants with preexisting depression, women, and Black participants, as well as those with vascular comorbid conditions. Addressing depression as a stroke risk factor along with vascular risk factors for primary stroke prevention may improve ambulatory status at discharge. More granular studies can be designed to determine the specific ways in which preexisting depression may affect poststroke ambulation or whether better management of depression in the outpatient setting reduces the risk of stroke.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating hospitals of the Florida–Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities registry.