Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a disorder associated with social and criminal transgressions. BvFTD is a progressive neurodegeneration of frontal and anterior temporal regions that usually presents with personality changes in midlife (

1). In addition to apathy, disinhibition, loss of empathy, stereotypies, and altered dietary behavior, the personality changes of bvFTD include a tendency for violation of social norms and even antisocial behavior. These transgressions, which range from shoplifting to the inappropriate touching of children, can result in criminal prosecution and incarceration (

2).

Although clinicians and investigators have long known that persons with bvFTD may engage in behaviors that constitute criminal transgressions, there is no critical review of this association and all the potential reasons for it. Understanding the processes that underlie antisocial acts in bvFTD could clarify the processes that underlie antisocial acts in general. The neuropathological localization of bvFTD is centered in mesial frontolimbic, frontoinsular, and anterior cingulate cortices, which contain Von Economo neurons evident in humans and other socially complex mammals (

3), and anterior temporal lobe structures involved in socioemotional processing (

4,

5). This neuropathological localization indicates a number of disturbances that can potentially result in violations of social norms and rules in bvFTD. This literature review gives a broad overview of criminal transgressions in bvFTD and the neurobiological processes that can contribute to their sociopathic acts.

CRIMINAL TRANSGRESSIONS IN bvFTD

Reports from around the world have established the association of increased criminal transgressions among persons with bvFTD when compared with healthy persons or those with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or other dementias (

6–

13) (

Table 1). In an early report from the United States (

6), 16 of 28 (57%) persons with bvFTD had sociopathic behavior such as unsolicited sexual acts and traffic violations, compared with only 7% of similarly impaired individuals with AD (

6). A subsequent, much larger U.S. study of the medical records of 2,397 persons with neurodegenerative diseases found prior criminal behavior among 37% (N=64/171) of those with bvFTD, compared with only 8% (N=42/545) of those with AD (

7). Those with semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) or semantic dementia (SD), a related frontotemporal dementia syndrome confined to the anterior temporal lobes, were also prone to criminal violations (27%; N=24/89). Persons with bvFTD and svPPA were about a decade younger than those with AD when their criminal transgressions were first noted. Moreover, 14% of the bvFTD group were first referred for diagnosis because of criminal behavior, compared with only 2% of those with AD.

Other investigators have reported similar findings from Europe and Japan. A German study of 83 patients found a history of criminal behavior in more than half of those with bvFTD (53%; N=17/32) or SD (56%; N=10/18), but only 12% (N=4/33) of those with AD (

9). In a Swedish cohort of 220 patients with pathologically verified dementia, higher criminal behavior and social inappropriateness occurred in 42% (N=50/119) of their patients with FTD syndrome, especially those with non-tau pathology, compared with only 15% (N=15/101) of their patients with AD (

11). A further evaluation of police interactions among 281 patients with pathologically verified dementia found that 26% (N=25/97) of the patients with FTD syndrome had police reports of criminal behavior versus only 9% (N=9/101) of the patients with AD (

12). Although some of the patients with bvFTD had early criminal behavior even before being examined by a physician (

12), criminal behavior occurred throughout the course of bvFTD, with over 80% with at least one or more offenses (

11). In one study, investigators were able to cross-check data for all Finnish patients from hospital discharges between 1998 and 2015 with all data from their police registry on criminal offenses from that period (

13). The crime rate was higher among 92,191 patients with dementia, compared with the general population, with at least one crime committed by 23.5% of men with FTD syndrome and 5.3% of women with FTD syndrome versus 12.8% of men with AD and 1.6% of women with AD, and 11.8% of men with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and 3.0% of women with dementia with Lewy bodies. During the 4 years preceding their FTD syndrome diagnosis, the incidence of crimes showed a substantially increasing trend among the men in this sample, with the first crime occurring on average 2.7 years (SD=1.1) before their diagnosis. Finally, Japanese investigators have reported high rates of law violations before initial consultation among 33% (N=24/73) of persons with bvFTD and 21% (N=18/84) among persons with svPPA, compared with only 6% (N=14/255) of those with AD (

10). In this study, 10 of the individuals with bvFTD had four or five violations before consultation, consistent with a high rate of recidivism (

10,

11).

The crimes committed by persons with bvFTD have included theft, sexual behavior, and traffic violations, as well as a range of other transgressions (

14). In a large U.S. study, crimes included trespassing, public urination, sexual advances or exposure, violence toward others, and driving infractions such as speeding, hit-and-run accidents, and driving under the influence (

7). Perhaps the most common crime in bvFTD is pathological stealing, such as taking something from someone or from a store without paying (

6,

7,

10,

15,

16). These acts are distinct from kleptomania in that the individuals with bvFTD lack anxiety beforehand or relief afterward, lack obsessional thinking, do not usually seek out opportunities to steal, and commit thefts only when items of interest are present.

Sexual transgressions are most commonly associated with either general disinhibition and poor impulse control or with compulsive tendencies, such as a need for repetitive kissing or an addiction to pornography (

17–

19). One report found a significant increase in sexual frequency among 13% (N=6/47) of those with bvFTD versus none of 58 with AD (

20). Paraphilic advances, including pedophilia, may emerge from disinhibition of lifelong and previously repressed predispositions (

19,

21–

24). Primary hypersexuality seems otherwise rare; however, some persons with bvFTD with right temporal involvement have manifested a dramatic increase in sexual frequency, actively seeking sexual stimulation, widened sexual interests, and sexual arousal from previously unexciting stimuli (

19).

In the Finnish study (

13), traffic offenses and crimes against property constituted 94% of all transgressions; violence, mainly assaults and illegal threats, was unusual. Several other reports indicate more violent or aggressive acts among persons with bvFTD compared with those with other dementias (

7,

25), but these acts appear reactive, not instrumental or planned. The Finnish researchers described one murder and one attempted murder in their FTD group (

13); in the Swedish series (

12), there was an attempt to use a car to injure others and the presence of homicidal and suicidal threats (

12). Nevertheless, despite historical interpretations of bvFTD as the source of prior notorious murders (

26), carefully thought-out or premeditated murder is unlikely in bvFTD.

Social Emotions

Most persons with bvFTD develop hypoemotionality—evidenced as decreased emotional displays and emotional reactivity—that significantly affects their caregivers (

115). Diagnostic criteria for bvFTD include many behaviors suggesting hypoemotionality, such as decreased engagement in previously rewarding activities, inability to initiate or sustain projects, diminished responses to interesting or novel events, and blunted emotional reactions in general (

1,

116). Persons with bvFTD have impairments in facial expressivity, especially in self-conscious reactions to negative facial emotions or to acoustic startle (

44,

117,

118). Others have described anosodiaphoria, or lack of emotional concern, in bvFTD, especially for how they are perceived or evaluated by others (

119,

120). Hypoemotionality in bvFTD is further evidenced as decreased psychophysiological arousal to affectively charged stimuli (

30,

121–

132), and there is decreased sympathetic nervous reactivity, particularly to complex or self-conscious emotions, even in the context of intact emotional and error awareness (

44,

121,

128,

131,

133–

136). In contrast, individuals with bvFTD may not reliably report their hypoemotionality, showing either alexithymia or altered emotional awareness despite intact or even exaggerated self-reports of their emotions based on interpretations of contextual cues or external rules (

128,

137,

138).

Self-Conscious Emotions

Not all emotions are affected equally in bvFTD. The most salient hypoemotionality in this condition involves self-conscious emotions, which require an evaluation of the self in social situations (

44,

134,

139). The experience of negative emotions, such as anger, disgust, fear, or sadness, are also affected but somewhat less so than self-conscious emotions (

27,

117,

134,

135,

140–

144), whereas positive emotions may be relatively preserved in bvFTD (

31,

44,

145,

146). Self-conscious emotions arise from the need to belong and conform, and they mediate obedience to social norms and rules (

147). Individuals with bvFTD have an overall diminished need or concern for social conformity and decreased self-conscious emotions, including the absence of guilt when engaging in transgressions (

2,

148). Other prototypical self-conscious emotions impaired in bvFTD include embarrassment, shame, pride, gratitude, compassion, fear of negative evaluation by others, and outrage at unfair treatment. They further include “fortune-of-other” emotions evoked via social comparison between one’s current status and that of another’s (

147), such as envy, jealousy, and schadenfreude, or pleasure at another’s misfortune.

Self-conscious emotional processing deficits in bvFTD are related to hypoactivity of a frontal-cingulate-insular circuit which includes the VMPFC, the pregenual and middle anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the AI, and other right-hemisphere regions, particularly the temporal pole (

41,

140,

149–

151). Individuals with lesions of the VMPFC, especially on the right with extension to the OFC, exhibit diminished emotional responsivity, intentional emotional imitation, and self-conscious emotions such as guilt, shame, and compassion (

152–

155). Pathology affecting the left frontal emotional regulatory circuits may heighten the more positive emotions and decrease the more negative ones (

145). Loss of gray matter in the right pregenual ACC in bvFTD is also associated with decreased embarrassment, guilt, and other self-conscious emotions (

127), and damage to the right AI is associated with a loss of emotional expressions (

44). Finally, extensive bilateral anterior temporal-amygdala involvement in bvFTD can produce the Klüver-Bucy syndrome with, among other symptoms, a pronounced unemotional passivity.

Empathy

A core diagnostic criterion for bvFTD, and a source of great distress for caregivers and others, is loss of empathy (

1,

2,

116,

156,

157). Empathy is the ability to recognize and appreciate the subjective experience of others (to share an isomorphic emotion of another human being) and reference it to oneself (

158). Caregivers and others describe persons with bvFTD, and especially those with prominent right anterior temporal involvement, as uncaring and lacking personal warmth (

117,

159). Empathy has both emotional aspects (affect sharing, emotional contagion, empathic concern, personal distress) and cognitive aspects (perspective taking, ToM, mental representations), with the most central aspect of empathy being emotional affective sharing or feeling “as” another (

160–

162). Although both emotional and cognitive empathy are impaired in bvFTD, this disorder is particularly associated with decreased affective sharing early in its course (

159,

163–

167). Affective sharing requires corepresenting or coregistering of perceived third-party emotions onto oneself (

168,

169). In other words, observing affective states in others activates corresponding first-person emotion areas in the observer, along with the associated physiological changes involved in the firsthand experience of those states (

170). In contrast, deficits in cognitive empathy in bvFTD seem to depend on the development of deficits in executive functions and in ToM (

171–

173).

Loss of empathy is a prominent feature of bvFTD not explained by loss of other social emotions, and loss of empathy goes beyond a general hypoemotionality. In bvFTD, loss of empathy persists despite covarying out for low emotionality to pictures (

174). Studies using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, which indicate reductions in both emotional and cognitive empathy in persons with bvFTD relative to those with AD and to neurologically healthy individuals (

72,

159,

164,

165,

175,

176), reveal lower empathic concern ratings in bvFTD, which cannot be explained by deficits in executive function, social cognition, or emotional recognition (

38,

159,

171,

175,

177). The absence of a clear relationship between the lack of empathic concern and facial affective expressions, skin conduction responses, or valence of stimuli in bvFTD further suggests a separation between empathy and basic emotional processing (

129,

164). In a study that used the performance-based Multifaceted Empathy Test, empathy for negative stimuli appeared particularly impaired in bvFTD (

160), and some investigators have proposed that in bvFTD the relatively preserved positive emotional reactivity undermines empathy by mitigating the negative emotional reactivity that more often motivates empathy (

117,

160).

Loss of empathy in bvFTD is related to pathology in a distributed network of regions centered on the frontal-cingulate-insular and temporal structures. These include frontal lobe (fronto-operculum, OFC, IFG), ACC (dorsal middle region; right subgenual), AI and right posterior insula, and right temporal lobe regions (amygdala, temporal pole, fusiform gyrus) (

133,

159,

164,

178–

181). Damage to both the AI and ACC is especially associated with impaired affective empathy (

182), as affective sharing depends on the salience network, an AI-ACC predominant network (

117,

131). Representations in AI underlie interoceptive awareness and representations of one’s own feeling states (

46), which in turn form the basis for the simulation of the feelings of others (

168). The ACC supports the integration of interoception and emotional salience for motivation and action choice (

46,

183). Finally, empathic processing involves the temporal lobe, including a semantic appraisal network for “emotional tuning” of semantic information in the right, more than the left, medial and lateral temporal cortex and amygdala (

149,

159,

181). Persons with bvFTD, particularly those with right temporal involvement, may incorrectly overestimate their capacity for empathy (

128,

160,

164). They can even show exaggerated displays of empathy, again reflecting an overdependence of empathic responsiveness on external context or environmental cues (

137,

138,

184).

Morality

Persons with bvFTD show defective moral reasoning and may engage in immoral acts despite their ability to describe the wrongness of their behavior and any potential consequences and punishments (

6,

185,

186). Morality is a code of values and customs that guides social conduct. Beyond codes of conduct held by societies, religions, legal systems, or groups, there is neurobiological evidence for an underlying universal moral code held by all rational people and driven by innate emotional drives, such as doing no harm within one’s own group, a sense of fairness and reciprocity, and group or community loyalty (

187). Moral emotional drives are rapid, involuntary, and intuitive reactions, which are distinct from deliberate moral reasoning (

188). Neurobiological evidence points to this automatic, emotionally mediated morality as being centered in the VMPFC, particularly on the right (

188), a focus of the neuropathology of bvFTD.

An early observation of persons with bvFTD was their tendency away from intuitive moral emotional reactions toward deliberate, utilitarian moral decisions based on “the greater good for the greater many” (

2,

185). When presented with a moral behavior inventory, persons with bvFTD described having normal moral responses despite engaging in social transgressions (

185). When presented with the most famous moral dilemma, the trolley problem, their “normal” moral responses were unemotional and utilitarian (

185).

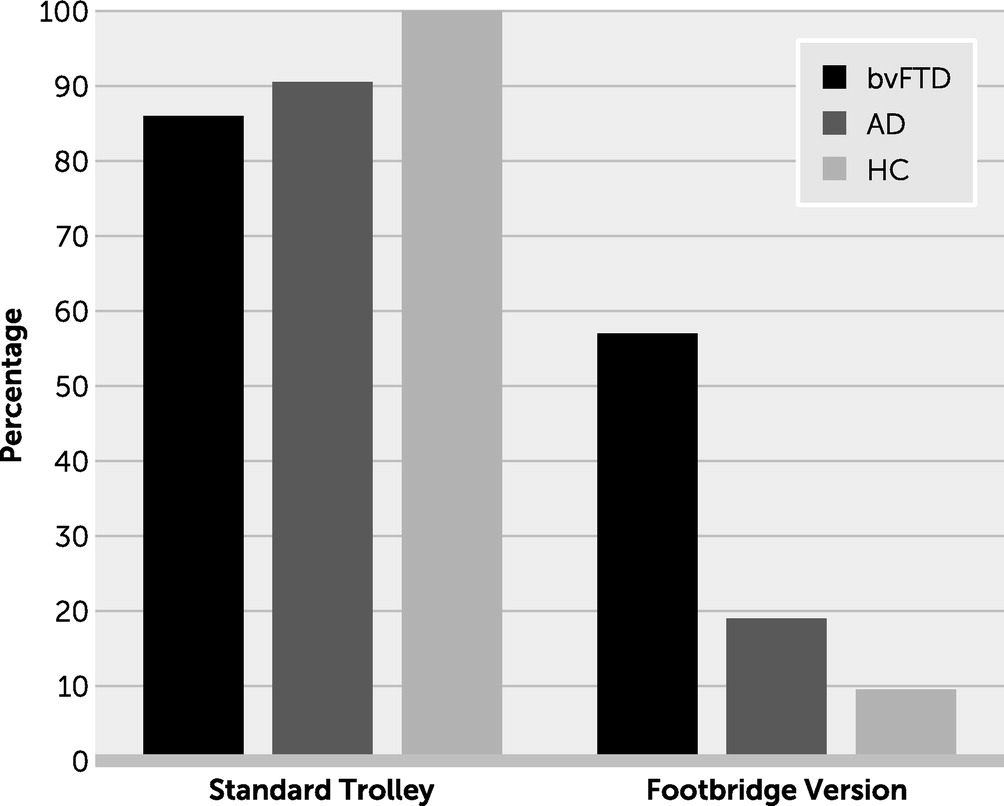

The two basic versions of the trolley problem presented participants with a runaway trolley that may kill five workers on the track. In the first version, the participant had to decide whether to flip a switch that would divert the trolley down a sidetrack, resulting in the death of only one large man lying on the sidetrack. This impersonal dilemma lacked the direct infliction of harm on another. In the second, “footbridge” version, the participant, who is now standing on a footbridge next to a large man, had to decide whether to push the large man onto the track, thereby killing him but stopping the trolley and saving the workers. This personal moral dilemma emphasized the participant’s own involvement and agency in inflicting harm. These trolley studies did not reveal significant differences between persons with bvFTD, those with AD, and healthy participants in preferring to pull the switch in the first version; however, in the second version only those with bvFTD were significantly more likely to be willing to push the large man in order to save the workers (

Figure 2) (

2,

185). Persons with bvFTD and those with traumatic brain injury made similar, significantly different utilitarian decisions during other personal scenarios involving the direct infliction of harm, whereas healthy individuals hesitated and reported discomfort (

2,

47,

185,

189–

193). When further studied, affective ToM and emotional arousal (skin conduction responses) were significantly decreased among those with bvFTD facing moral dilemmas (

156,

189). In these individuals, decreased conflict or discomfort with personal moral dilemmas was also correlated with a measure of social norms violations (

14,

188).

Morality involves a number of frontal lobe regions: the VMPFC, OFC, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (

194,

195). On the moral dilemmas, increased endorsement of personal harm is particularly associated with VMPFC damage, especially on the right, in persons with bvFTD and traumatic brain injury (

185,

196–

199). Early-life lesions in the VMPFC and adjacent areas can impair the development of moral knowledge or decisions that avoid harm to others (

200). Individuals with damage to the VMPFC may not foresee negative emotional reactions when contemplating directly harming another person (

201,

202); however, when faced with indirect or incidental harm to others, they are able to use reason for the greater good (

185,

196–

198,

200,

203). It appears that the VMPFC assigns emotional valence to social scenarios; when damaged, it prevents the normal emotional aversion for social or criminal transgressions.

There are several conclusions from the studies of moral reasoning in bvFTD (

Box 1). First, in the absence of a strong negative emotional reaction to the perception of harming another, persons with bvFTD and those with damage to the VMPFC do not experience an emotional aversion and instead rely on cognitive processes to access apparent moral decisions. They lack discomfort or distress or physiological arousal in making moral decisions. Second, these individuals perform comparably to control subjects on impersonal harm dilemmas, yet they display an abnormal pattern of utilitarian judgment during personal harm scenarios that normally evoke strong negative reactions. Third, persons with bvFTD compared with control subjects have impaired integration of others’ intentions, which are necessary to override responses to negative outcomes, and they judge attempted harm as more permissible and accidental harm as less permissible (

204). Fourth, they are more rule-based and dependent on social rules or context rather than care-based and dependent on another’s perceived welfare (

205). Finally, despite knowing the nature and potential negative results of their actions, their moral reasoning lacks responsiveness to the consequences of their decisions (

206).

Conclusions

The literature indicates multiple (albeit overlapping) mechanisms for the predisposition to social and criminal transgressions among persons with bvFTD. These include disturbances in basic aspects of social cognition, such as abnormalities in social perception, behavioral regulation and control, and ToM or mentalizing. Disturbed social perception in bvFTD goes beyond just impaired recognition of facial or other emotional cues. It includes a disturbance in the appreciation of animacy or of being a living entity and the state of being a living human. Social emotions are disturbed, including not only self-conscious emotions such as guilt or embarrassment but also empathy and affect sharing. Furthermore, bvFTD impairs an innate universal morality despite retaining knowledge of right and wrong and of social rules and norms. Critically affected structures that predominantly involve the right hemisphere include the VMPFC for emotional labeling, the OFC and the IFG for inhibition and operant learning, the AI for emotional awareness, the ACC for limbic responsiveness, and the anterior temporal lobe, which can contribute through emotional recognition and other mechanisms.

This review suggests that impairment in brain mechanisms involved in the emotional processing of others, along with disinhibition, constitute the necessary elements for social and criminal transgressions in bvFTD. The contribution of individual neurobiological processes can vary across individuals and may indicate clinical subtypes of bvFTD. Investigators need to disentangle the contributions of each of these processes to antisocial behavior. Understanding these processes may lead to a battery for assessment that can be applied to individuals with antisocial behavior in general, but especially those with new-onset antisocial behavior in later life, who may have neuropathology. It is conceivable that this could lead to neurobiological profiles underlying antisocial acts, so that in the future there could be behavioral strategies, pharmacological treatment, preventive measures, better support for caregivers, and other methods specifically targeted to the neurobiological mechanisms that underly antisocial behavior not only in bvFTD but in all individuals who engage in antisocial acts.