The field of neuropsychiatry has been variously defined by the types of disorders treated, the diagnostic or investigational techniques utilized, its differentiation from a purely psychologically based psychiatric paradigm, the application of both psychiatric and neurological skills with neuropsychological techniques in diagnosis and treatment, or the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric comorbidity associated with brain abnormalities and neurological comorbidity associated with psychiatric disorders (

1–

9).

The term neuropsychiatry came into use in the United States in the closing stages of World War I in response to the military's need for specialists in the diagnosis of what are now called functional neurological disorders, and it enjoyed increased popularity, in contradistinction to psychoanalysis, after World War II. The term reemerged with the availability of more sophisticated neuroimaging techniques, advances in psychiatric neuroscience, the maturation of psychopharmacology, and the growth of neuropsychology and cognitive science (

7). This reemergence was also facilitated by the rise of behavioral neurology as a neurological subspecialty (

1). Amid the increased interest in neuropsychiatry, the British Neuropsychiatry Association was founded in 1987, and the American Neuropsychiatric Association (ANPA) and

Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences were established in 1988.

Neuropsychiatric specialty or subspecialty training may be obtained by completing residency training in both neurology and psychiatry, either by serial residencies or in a combined neuropsychiatry residency program, or by pursuing fellowship training in behavioral neurology & neuropsychiatry (BNNP) following residency training in either neurology or psychiatry. Graduates of dual-specialty residencies are eligible to take the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) board certification examinations in both neurology and psychiatry. Graduates of BNNP fellowship programs accredited by the United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties (UCNS) are eligible to take the UCNS certification examination in the subspecialty of BNNP following primary ABPN specialty certification.

In the present article, the term “combined training” refers to residencies that fulfill the requirements in both psychiatry and another field of medicine. “Combined neuropsychiatry program” refers to a single residency program that fulfills all criteria for both the psychiatry and neurology specialties. “Dual trained” refers to physicians who complete training in psychiatry plus another field of medicine that may or may not be part of a combined residency program. “Dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists” may have completed separate psychiatry and neurology residencies in series, at different times, or in a combined program. The term “neuropsychiatrist” is used by physicians who have completed training in both psychiatry and neurology, by physicians who have completed BNNP fellowship training, and by some physicians who have completed a residency in either psychiatry or neurology and specialize in the treatment of conditions considered to be “neuropsychiatric.” The terms “double boarded” and “dual boarded” are used to describe psychiatrists who are ABPN certified in both psychiatry and neurology. This article describes physicians who completed residency training in both neurology and psychiatry. The number who self-identify as neuropsychiatrists is not known, and therefore the term “neurologist-psychiatrist” is used when identity as a neuropsychiatrist is uncertain.

Limited information about the practice patterns of dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists is available to guide prospective applicants to combined neuropsychiatry residency programs. A 1986 survey of dual-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists compared disorders treated among 23 self-designated neurologists, nine self-designated psychiatrists, and 21 physicians self-designated neuropsychiatrists or dual neurologist-psychiatrists (

3). In a 2008 survey of 555 double-boarded psychiatrists holding boards in internal medicine, family practice, or neurology and the same number of single-boarded psychiatrists, Summergrad et al. found that the double-boarded psychiatrists were more likely than the single-boarded psychiatrists to occupy academic leadership positions and that neurologist-psychiatrists were more likely than other combined psychiatry specialists to continue practicing in their nonpsychiatric medical specialty (

10). In 2021, a survey was undertaken to understand the current practices of U.S. dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists and the perceived value of their dual training. This article will review the history of dual training and certification in neurology and psychiatry, highlight the unique issues facing combined neuropsychiatry residency programs, and present data from the 2021 survey. The general history of neuropsychiatry has been covered in numerous publications and will not be discussed in this article (

2,

5–

7,

11–

21).

Part 1: History

Dual Board Certification in Psychiatry and Neurology

The history of dual certification in psychiatry and neurology is best understood as part of the history of the ABPN. The ABPN was formed in December 1933 at a meeting of representatives of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the American Neurological Association (ANA), and the American Medical Association (AMA) Section on Nervous and Mental Disease. The meeting was held under the auspices of the AMA Council on Medical Education and Hospitals. Representatives of the AMA Section on Nervous and Mental Disease favored the creation of board certification in neuropsychiatry and had preliminary plans to implement such certification on their own prior to this meeting (

22). Prior to the December 1933 meeting, there were discussions within APA of establishing a board for certification of psychiatrists only. The APA representatives saw less benefit in extensive training in neurology and favored certification as psychiatrists.

The representatives of the three organizations (APA, ANA, and AMA) voted to form the ABPN with equal representation from the two specialties, with the order of specialties in the board’s name being ultimately determined by the size of each specialty. Coming to agreement on standards for board certification was no mean feat, because some of the psychiatrists in the group had been trained in the older European method that progressed from the study of neuroanatomy, neuropathology, and neurology to the study of neuroses and psychoses, while some had been trained in the new world method of focusing on psychological and philosophical aspects of psychiatry (

22). The representatives at the December 1933 meeting were practitioners who defined themselves as neurologists, neuropsychiatrists, and psychiatrists. The board was initially composed of an equal number of psychiatrists and neurologists and included four representatives of the APA, four representatives of the ANA, and four representatives—two from each field—of the AMA Section on Nervous and Mental Disease.

At the 1933 meeting, the representatives debated the future of neuropsychiatry as a specialty and the desired relationship between the two fields. Adolf Meyer, who had served as APA President in 1927–1928, was an outspoken participant in the meeting. He had been trained as a neuropathologist before coming to the United States, briefly taking up a post at Kankakee State Hospital in Illinois and moving to Worcester State Hospital in 1895. There he founded a psychiatry training program in the European tradition of studying neuroanatomy and neuropathology as part of training. By the time of the 1933 meeting, he had moved on to serve as founding chair of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins. Meyer, who felt strongly that psychiatrists should have training in neurology, neuropathology, and neuroanatomy, as well as what he called psychobiology, realized that compromise was needed:

I am perfectly willing to look upon my own use of the term neuropsychiatry as a pious wish that there should be as many neurologists as I hope there will be psychiatrists who want to pool their domains…. I wish that for every psychiatrist there might be a demand of adequate knowledge of what the nervous system can do, so that we might avoid leaving many thinking that they can take up psychiatry from the spiritual end exclusively. (

22)

Clarence Cheney, another APA representative, responded as follows:

There are many persons who wish to be called neuropsychiatrists and that is just the thing it is wished to get away from… (

22)

Walter Freeman, an AMA representative who favored the notion of neuropsychiatry and would later become known for promulgating the prefrontal leukotomy, argued for a close relationship of neurology and psychiatry:

It would be much better to band together, to be known as those who are dealing with the nervous system rather than to split them apart into the organic neurologist and the functional psychiatrist. (

22)

Henry Riley, an ANA representative, and Edwin Zabriskie, an AMA representative, agreed with Freeman. There was a good deal of tension to overcome at the meeting, because the APA representatives were focused more on psychiatry and psychoanalysis, while the AMA representatives defined themselves as neuropsychiatrists.

The first ABPN certification examinations were held in 1935. Depending on the candidate’s goal, examinations would focus on certification in either neurology or psychiatry or both, with examinations given personally by the board directors. The examinations included neuropathology (10 gross and 10 microscopic exhibits), psychobiology (oral questioning), psychopathology (written questions), radiology (six X-rays), neuroanatomy (oral and written), clinical neurology (patient examination), and clinical psychiatry (patient examination) (Dorthea Juul, Ph.D., Vice President, ABPN, personal communication, May 7, 2021). The early board examinations were unique experiences. At the first examination, for example, Adolf Meyer is said to have asked each candidate to trace the path of a bullet from a particular entrance point through the brain (

22).

From its formation until 1959, the ABPN awarded certification in neuropsychiatry either to individuals who passed both examinations at once or to individuals who had the requisite training and whose credentials in both fields were recognized by the board directors. In 1967, to encourage candidates to become certified in both fields, the ABPN decreased the time requirement for combined training to 6 years but specified that it include 2 years of training in each field and 2 years of experience in either or both fields. From 1972 to 1984, 5 years of training were required. Since 1985, a minimum of 6 years of training in the two fields have been required. The evolution of ABPN requirements for admission to both the psychiatry and neurology board examinations is shown in Table S1 in the online supplement.

The ABPN examinations have continued to evolve. From 1967 to 2011, passing a Part One written examination specific to psychiatry or neurology was required to qualify for a Part Two oral examination in that field. Oral examinations in either field were conducted by two examiners who observed the candidate examine a patient and then questioned the candidate as they presented a differential diagnosis, treatment plan, and prognosis. Initially, the oral examination in each field included examination of a patient with a problem in the opposite field. In the years prior to the elimination of the Part Two oral examination, one of the patient examinations was replaced with a series of brief oral vignettes. Then, for those beginning neurology training after July 1, 2005, or psychiatry training after July 1, 2007, oral examinations were no longer required. The oral examinations were replaced by a series of observed clinical interviews conducted by faculty during residency training as qualification to sit for a written examination. Candidates seeking board certification in neurology and psychiatry must complete the entire process in both fields. Individuals certified after October 1, 1994, are issued 10-year time-limited certificates and are required to maintain their certification by maintaining active licensure, earning continuing education credits, performing practice quality improvement (“performance in practice”) or patient or peer feedback modules, and either passing a written examination every 10 years or taking quizzes on a series of articles selected by relevant ABPN committees.

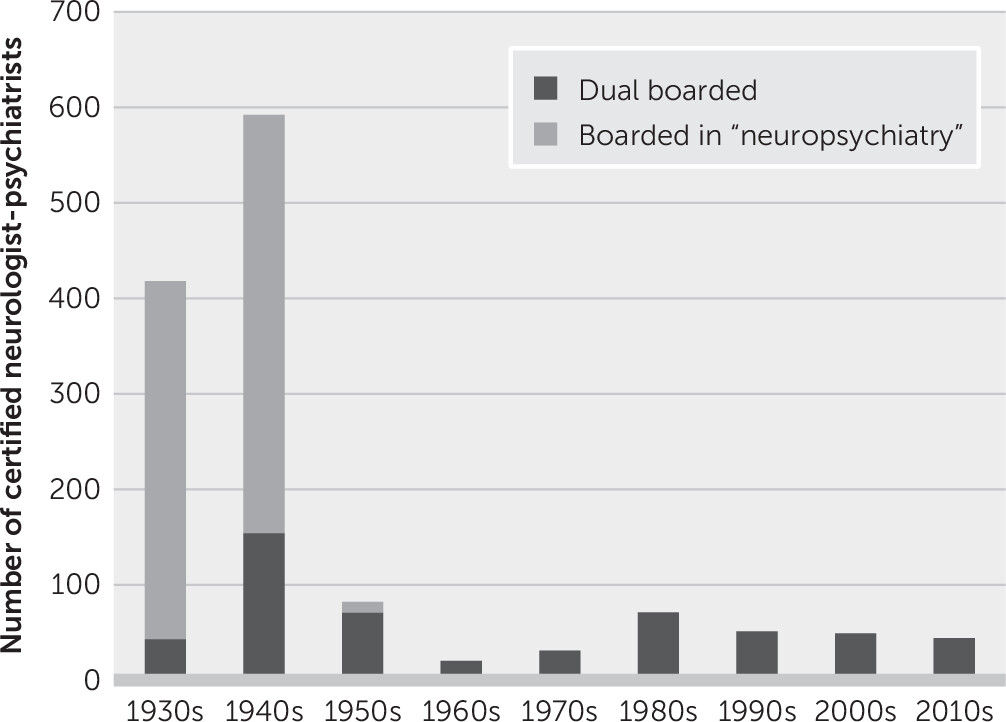

A total of 824 physicians were certified by the ABPN in the specialty of neuropsychiatry from 1935 to 1959, when the last ABPN neuropsychiatry certification was recorded. Neuropsychiatry diplomates included both those who were certified on their record and those who were certified by passing both examinations in one session. An additional 537 physicians were certified in both neurology and psychiatry from 1935 to 2020, including both graduates of combined training programs and physicians who completed dual training in two separate programs either serially or at different times.

Figure 1 illustrates the number of neuropsychiatry diplomates of each type by decade. Nine recent graduates of combined neuropsychiatry programs included among the 537 physicians described above passed boards in both fields during the same examination session. The average time between board examinations among the remaining 528 physicians was 3.5 years, with 54% passing psychiatry first.

Altogether, a total of 1,361 double-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists were certified from the introduction of the ABPN examination through 2020; the number who practiced at the interface of the two fields or self-identified as neuropsychiatrists is not known. Over the first decade of the ABPN examination process, neuropsychiatry certifications decreased from 49% to 27% of diplomates. From the first ABPN examination in 1935 until the last neuropsychiatry certification was awarded in 1959, 16% of board certifications were dual. From 1935 to 1945, however, an average of 36% of board certifications were based on passing both specialty examinations in a single session. For comparison, only three of the 2,812 diplomates certified in psychiatry and neurology in 2020 were dual boarded. There was a dip in new dual-boarded neuropsychiatrists in the 1960s and 1970s that corresponded to a rise in popularity of psychodynamic psychotherapy as the core curriculum of American psychiatry residency programs (

Figure 1). The composition of the ABPN itself reflects the 20th-century trend in dual boarding. Forty-seven of 62 ABPN directors (76%) appointed from its founding in 1934 through 1965 were dual boarded (

23). Of the 15 directors who were not dual boarded in those years, 13 were boarded in psychiatry, one in neurology, and one, a psychiatrist, was never certified. Of the directors appointed in the ensuing 55 years, only two have been dual boarded, including the author of the present article.

Combined Neurology-Psychiatry Residency Training Programs

Prior to the formation of the ABPN, the curricula, length, and amount of residency training in the complementary fields varied considerably among programs. Combined training programs in neurology and psychiatry existed in the United States at the time the ABPN was formed, but these programs decreased in number over the ensuing decades as the field of neurology expanded. In 1953, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs indicated an interest in providing combined training in neurology and psychiatry to better serve World War II veterans (

24). However, the ABPN has no evidence that the military developed a formal combined program.

Absent prior approval by the ABPN or participation in a combined training program in neurology and psychiatry, 7 years of residency training are currently required for board eligibility in both neurology and psychiatry. Combined training programs in neurology and psychiatry decrease the total number of years of required training by 1 year by allowing the resident to substitute 6 months of training in the opposite field for the same amount of elective time. There is no difference in the content of training between combined programs and separate residencies in each field. But combined programs often provide the resident with experience at the interface of the two fields.

As of 1987, to ensure compliance with all training requirements, the ABPN began to approve specific 6-year combined neurology-psychiatry residencies that provide the full-time equivalent of 2 years of psychiatry training and 2 years of neurology training following a medical internship and culminate in 1 year that is jointly supervised by neurology and psychiatry. From 1987 until 2016, the ABPN also allowed accredited neurology and psychiatry programs to create 6-year combined neurology-psychiatry residencies on an ad hoc basis if the curriculum included all of the timed requirements in each field. Historically, some combined programs satisfied the requirements in both fields but did not have a dedicated neuropsychiatry service or clinic. These programs, like the ad hoc programs, may have been less likely to continue to recruit trainees than programs with dedicated clinical neuropsychiatry services. From 2010 to 2014, the ABPN temporarily halted the approval of new combined training programs in psychiatry or neurology pending establishment of an oversight mechanism, because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) indicated that they could not provide specific accreditation for smaller combined specialties. In 2014, the ABPN created an Alternative Pathways Oversight Committee to verify that the curricula of combined training programs met all requirements in their respective host fields. This committee reviews all established and proposed combined psychiatry or neurology programs for compliance; these combined programs include psychiatry and internal medicine; psychiatry and family medicine; psychiatry, pediatrics, and child psychiatry; psychiatry and neurology; neurology and internal medicine; and post-pediatrics portal programs in child psychiatry.

Unique Issues in the Establishment of Combined Neurology-Psychiatry Residency Programs

Combined training, as opposed to serial specialty training, has the unique goal of graduating residents with a professional identity as a neuropsychiatrist, rather than separate identities as a psychiatrist and a neurologist (

25). In the view of the author, the success of a combined neuropsychiatry program depends on a close working relationship between the host departments, a dedicated neuropsychiatry service, an agreed-upon administrative structure, appropriate clinical and didactic curricula, and adequate funding. Excellent communication between the two host departments is especially important because the residents move back and forth between the departments frequently during training, vacation and conference time needs to be split fairly, and recruitment depends on the support of faculty and trainees in both host departments. One of the host departments will likely have to provide the bulk of administrative support for consistency in managing the recruitment season, in tracking timed requirements for reporting to the ABPN credentialing system (i.e., PreCERT), and in managing leave time and other benefits.

Both host programs must have full ACGME accreditation to apply for the establishment or maintenance of a combined residency program. The two departments must establish a combined clinical competence committee charged with reviewing resident performance, assigning milestone ratings in both psychiatry and neurology for report to the ACGME, and prescribing any needed remediation. The 6 years of required training must include an internship with at least 8 months of medicine or primary care training and no more than 2 months of neurology training and 2 months of psychiatry training. The internship must be followed by 30 months of full-time equivalent training in each field. Combined neuropsychiatry programs may be led by either one board-certified program codirector from each host department or a double-boarded program director. The complete requirements are available from the ABPN (

26).

To ensure that residents receive adequate experience in the diagnosis and treatment of the neurological, cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric aspects of conditions such as dementia, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, movement disorders, autoimmune disorders, stroke sequelae, and neurodevelopmental disabilities, I contend that a dedicated neuropsychiatric service is an important component of training, although this is not specified in the official requirements. Examples of neuropsychiatric services include neuropsychiatry outpatient clinics, inpatient consultation services, and inpatient units. Within this environment, training is enhanced by case conferences, journal clubs, and interdisciplinary exposure to BNNP, neuropsychology, neuroradiology, neuropathology, neuroimmunology, speech pathology, occupational and physical therapies, and other neurorehabilitation specialties (

27,

28).

Funding of a combined residency training program requires the cooperation of both host departments, the sponsoring institution, and the graduate medical education committee. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) funds the bulk of U.S. graduate medical education. Hospitals receive direct funding to cover residents’ salaries and benefits and indirect funding to help defray the higher cost of academic health centers compared with other hospitals. The number of fully paid graduate medical education positions is capped for each hospital. Residents are considered to exceed the cap once they have completed the 4 years required for single-board eligibility. Although hospitals receive 100% of their indirect CMS payment for all 6 years of combined training in neurology and psychiatry, they receive only 50% of direct costs for trainees in excess of the cap. Thus, the sponsoring institution or departments must be willing to incur a higher cost for residents in the fifth and sixth years of training in combined residency programs. The inability to cover the full costs of all 6 years of training with CMS funds in tight health care funding environments has been cited by a few institutions as a reason for closing their combined neurology-psychiatry programs. On the other hand, some hospitals consider the availability of dual neurology-psychiatry trainees to manage patients with complex and potentially highly resource-consuming conditions to be well worth the added costs of a combined program.

Part 2: Survey of Dual-Trained Neuropsychiatrists

Dual-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists, graduates of combined neuropsychiatry residency programs in the United States, and residents currently in combined neuropsychiatry training programs were surveyed in 2021 to understand their clinical practices, academic roles, and perceptions of the value of dual residency training in neurology and psychiatry.

The survey project was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts T. H. Chan School of Medicine. A list of the 1,361 physicians certified in both psychiatry and neurology since 1935 was obtained from the ABPN. In addition, a list of the 75 alumni of combined neuropsychiatry residency programs, both active and inactive, was compiled by contacting the physicians’ current or former training directors. Forty-three alumni from combined neuropsychiatry programs were board certified in both psychiatry and neurology, 18 were certified in psychiatry only, four were certified in neurology only, and 10 were not certified by the ABPN. To exclude individuals who were deceased, the survey coordinator conducted an Internet search of the 280 dual-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists certified after 1954 (202 were living) and the 32 combined neuropsychiatry program alumni who were not boarded in both fields (32 were living). E-mail contact information was obtained from a direct request to the physician or from a search of available online membership databases through the online portals of APA, American Academy of Neurology (AAN), ANPA, LinkedIn, or Doximity, state medical boards, and medical school faculty lists. In some cases, PubMed was used to search for corresponding author e-mail addresses. Additional e-mail contact information was obtained by an Internet search and telephone requests. The final survey population for whom email addresses could be located included 207 physicians who, as of May 2021, had completed residency training in both neurology and psychiatry and 18 combined neuropsychiatry residents in training (for a flowchart of the respondents, see Figure S1 in the online supplement). The questions in the survey distributed to the 18 residents were modified for appropriateness to residents in training.

Survey requests were e-mailed to the 225 recipients identified above by using Survey Monkey (

https://www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was anonymous. The software platform was used to e-mail nonresponders twice to maximize the response rate. The survey contained one open-ended opportunity for the respondent to make any comments about dual training. Open text responses were assigned any of eight keyword tags to allow sorting by subject matter.

A total of 133 physicians who had completed residency training in both neurology and psychiatry completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 64%. Among them, 117 (88%) respondents were double boarded in neurology and psychiatry by the ABPN. The respondent group included 42% of all neurologist-psychiatrists who had been dual boarded since 1955 and 58% of those thought to be living at the time of the survey. Respondents who were board certified by the ABPN in both neurology and psychiatry included 61 alumni of combined neuropsychiatry programs and 72 who completed separate residencies. Responses from the 52 combined program alumni who were double boarded were generally similar to the responses from the 16 respondents who were not double boarded. One hundred percent of the 18 residents in the four currently active combined neuropsychiatry residency programs responded to a parallel version of the survey.

Demographic Data and Training History of Survey Respondents

Demographic data of the survey respondents are presented in

Table 1. Men comprised 74% of the sample, and women comprised 24%. One respondent completed training in the 1960s; 10, in the 1970s; 31, in the 1980s; 25, in the 1990s; 34, in the 2000s; 28, in the 2010s; and four, in 2020. Respondents were asked to categorize any fellowships as either a psychiatry or a neurology subspecialty. Of the 133 respondents who completed residency in both psychiatry and neurology, 89 (67%) completed fellowships after residency, 36 (27%) of which were in psychiatry subspecialties, and 53 (40%) were in neurology subspecialties. Psychiatry fellowships completed by four or more respondents included research (N=7), forensic psychiatry (N=5), geriatric psychiatry (N=4), sleep medicine (N=4), BNNP (N=4), child and adolescent psychiatry (N=4), epilepsy and clinical neurophysiology (N=4), and psychotherapy or psychoanalysis (N=4). Neurology fellowships completed by four or more respondents included epilepsy and clinical neurophysiology (N=15), BNNP (N=9), movement disorders (N=8), research (N=6), and sleep medicine (N=5). Of those who completed subspecialty fellowship training in either specialty, a total of 19 respondents (14%) completed epilepsy and clinical neurophysiology fellowships, 13 (10%) completed BNNP fellowships, and nine (7%) completed fellowships in sleep medicine.

Board Certification

Among the 133 dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrist survey respondents, 117 (88%) were ABPN certified in both psychiatry and neurology, 12 (9%) were certified in psychiatry only, two (2%) were certified in neurology only, and two (2%) were not certified in either specialty. Thirty-seven respondents (28%) held an additional ABPN subspecialty certification. Twenty-one respondents (16%) were certified in BNNP by the UCNS, and six were certified by the UCNS in a different subspecialty. Two of 61 graduates of combined neuropsychiatry programs (3%) held no board certification. Thirty-seven respondents had nonexpiring ABPN board certifications, and 56 (42%) were enrolled in continuing certification in both psychiatry and neurology.

Practice Description

Descriptive information about the practices of neurologist-psychiatrists who completed residency training in both fields is also summarized in

Table 1. Eighty percent of respondents practice in cities with populations greater than 100,000. Dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists were 1.7 times more likely to identify psychiatry rather than neurology as their primary departmental affiliation. Forty-seven respondents (35%) reported practicing in a university-affiliated academic health center, 39 (29%) were in solo or group private practices, eight (6%) worked in veterans’ hospitals, six (5%) worked in state hospitals, and six (5%) worked in private hospitals. Sixteen respondents (12%) were retired or not working as a physician at the time of the survey.

Medical students may be advised incorrectly that graduates of combined neuropsychiatry residencies end up practicing in one field or the other exclusively. Of the 111 respondents still in practice and not engaged in full-time research, 51 (46%) practiced both neurology and psychiatry, and of those who identified as practicing psychiatry only, many volunteered that they often see patients with neuropsychiatric conditions. In the Summergrad et al. study, psychiatrists with combined training were significantly more likely than psychiatrists who switched to psychiatry from other medical specialty types to practice at least 25% of the time in the complementary medical specialty (

10). In the 2021 survey discussed here, 57 (51%) practicing dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists practiced neurology ≥20% of the time.

Although the majority of respondents identified psychiatry as their primary departmental affiliation, 68% of dual-trained respondents were members of AAN, and 52% were members of APA. Forty-two percent of respondents were members of ANPA, while only 3% were members of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology.

The various roles that respondents have held in their careers are summarized in

Table 1. Ninety percent of respondents have worked in outpatient settings, and 72% have worked in inpatient settings. Fifty-six respondents (42%) have held leadership roles in their department or hospital. Seventy-eight respondents (59%) engaged in teaching at the medical student, resident, or fellowship level. These data are consistent with a 2008 survey that found double-boarded psychiatrists to be significantly more likely than single-boarded psychiatrists to have held leadership positions in medicine (

10). The degree to which dual-trained neuropsychiatrists engage in academic activities is described in

Table 1. Although no published standards for comparison could be identified, the fact that 71% of respondents had published articles in peer-reviewed journals, 29% had conducted funded research studies, and 21% had published books speaks to the academic productivity of the neuropsychiatrists who completed dual residency training.

Respondents were asked to select the five diagnoses they see most frequently in their practices, and their responses are presented in

Table 1. The 1986 survey conducted by Fogel and Schiffer did not ask about primary psychiatric diagnoses or headache, but five out of six most frequent neurological diagnoses in their study were concordant with those of the 2021 survey discussed here (

3).

Perceived Value of Dual Residency Training in Neurology and Psychiatry

Several findings that might be helpful to individuals considering dual neurology-psychiatry residency training are presented in

Table 2. Among the dual-trained survey respondents, 96% reported feeling better prepared for practice than they would have with single-specialty training. The fact that 93% of respondents felt their approach to patients differed from that of their psychiatry or neurology colleagues and that 92% and 94% of respondents felt that they treated conditions normally not treated by neurologists or psychiatrists, respectively, speaks to the identity of neuropsychiatry as a distinct subspecialty. Also striking was the number reporting enhanced career satisfaction (93%), with 45% of respondents feeling that their dual training made them less susceptible to burnout.

Given space to “enter any additional comments about the value of combined neuropsychiatry residency training, advice to students, or any related topics,” 49% of respondents offered comments. Among the comments, 84% were extremely positive about the value of combined neuropsychiatry training. Thirty-four of the 74 respondents (46%) who offered comments reported that dual training in neurology-psychiatry made them better diagnosticians. A number of respondents commented on how intellectually satisfying they found dual training to be and how much their training enhanced their practice. These findings concur with those from the 1986 Fogel and Schiffer survey of dual-boarded neuropsychiatrists, in which 94% of respondents endorsed the value of dual training and felt that their training in the opposite field made them better practitioners in their primary field (

3). When respondents in the 2021 survey were asked whether their dual training had a beneficial effect on their earning potential, however, the responses were evenly divided.

Residents Presently in Combined Training

All 18 residents who were enrolled in the four combined neuropsychiatry residencies at the time responded to the survey in the spring of 2021. When asked about their fellowship plans, none were actively considering psychiatry subspecialty fellowships, although 35% were uncertain at the time of the survey. On the other hand, five respondents (28%) planned on entering neurology subspecialty fellowships at the conclusion of residency, and 30% were uncertain. Fourteen respondents (78%) had published in or submitted papers to peer-reviewed journals, and seven (39%) had published or were writing book chapters. Fifty percent of respondents had presented at national meetings, 50% had created curricula, and 33% had served as peer reviewers. The opinions of current residents on the value of combined training were similar to the opinions of practicing neuropsychiatrists (

Table 2).

Discussion

Dual residency training as a pathway to neuropsychiatry dates back to the early 20th century and predates the establishment of the ABPN. The decreasing emphasis on dual neurology-psychiatry residency training by the ABPN occurred in the context of growth in the number of academic neurology departments and was associated with a reduction in the number of dual training programs nationally. The reemergence of neuropsychiatry in the 1970s and 1980s led to the establishment of 13 combined neuropsychiatry programs over a 40-year period, with approximately four or five actively recruiting in any given year, which is consistent with the four currently active ABPN-approved programs in the United States. These programs are Medical University of South Carolina, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, University of Massachusetts T. H. Chan School of Medicine, and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

As a group, physicians who have completed residency training in both psychiatry and neurology are extremely positive about their choice of training path. They feel that they are better prepared for their positions, are more competitive for jobs, approach clinical problems differently, and treat conditions their single-specialty colleagues do not. The majority have held clinical or academic leadership roles, conducted scholarly activity, or both.

At a time of rapid advances in the psychiatric neurosciences and the growing availability of sophisticated neurogenetic and neuroimaging diagnostic tools, it is reasonable to ask why there has not been a concurrent increase in the number of combined neuropsychiatry residency programs. The reasons for this are likely complex. Based on the author’s discussions with combined neuropsychiatry residency program directors, past and present, these reasons include the following: lack of experience with combined neuropsychiatry residency programs on the part of neurology and psychiatry department chairpersons; lack of knowledge about combined neuropsychiatry residency training on the part of those who provide career advice to medical students; funding constraints that keep hospitals from investing in longer courses of training that would require more positions in excess of the CMS resident position cap; high medical student debt that discourages trainees from undertaking longer residencies; generational changes in attitudes toward longer training programs; absence of the close working relationship between departments of psychiatry and neurology needed for combined training; competition for hospital support of new residency programs from emerging subspecialties and growth in primary care training; dearth of BNNP faculty needed for training; absence of dedicated neuropsychiatry clinics, consultation services, or inpatient units; and departmental or hospital educational leadership who oppose the idea of combined training programs on philosophical grounds. Reasons for program closures in the past 30 years have included budgetary limitations; a desire to focus available resources on research training; retirement or departure of the sponsoring program director; failure to recruit in the match during the 1990s when fewer medical school graduates were entering psychiatry training overall; closure in the aftermath of a disaster; insufficient interest on the part of a new department chairperson; and an inaccurate perception that the ACGME and ABPN would no longer allow this training pathway, fostered by the ABPN moratorium on the establishment of new combined training programs from 2010 to 2014.

Two-thirds of dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists have undertaken additional fellowship training. Of these, 46% have completed fellowships in neurophysiology, epilepsy, BNNP, or sleep medicine.

Dual training is only one pathway toward becoming a neuropsychiatrist. Fellowship training is the other major pathway. The 407 physicians with UCNS certification in BNNP as of 2021 are about 1.5 times as numerous as the estimated 280 dual-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists.

For patients experiencing neuropsychiatric conditions, dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists may be able to provide an explanation for confusing symptoms that have eluded diagnosis, to provide multimodal care for complex disorders that might otherwise require multiple specialists, and to enhance the quality of life among patients with such disorders. Some examples include mood or psychotic disorders among people with epilepsy, movement disorders, dementia, demyelinating disease, autoimmune disorders, stroke, functional neurological disorders, and neurodevelopmental disabilities; neurological disorders among people with schizophrenia; and neurocognitive symptoms of unknown etiology. Within health care systems, neuropsychiatrists care for patients that other physicians do not or will not treat and manage complex conditions in a more cost-efficient manner than would occur with the involvement of multiple specialists. Within the context of a training program, dual-trained neuropsychiatrists are able to teach the diagnosis and management of complex neuropsychiatric disorders. For trainees, dual-trained neuropsychiatrists expand the concept of biological psychiatry to include neuroanatomy, neuropathology, neurophysiology, genetics, neuroimaging, neuromodulation, cognitive science, and psychopharmacology and add a brain-based perspective to the biopsychosocial model of formulation practiced in psychiatry (

29).

This survey did not directly ask whether the respondent self-identified as a neuropsychiatrist. It is possible that some dual-trained neurologist-psychiatrists undertake the second training in order to switch careers rather than combine the fields. It is not known whether this self-identification may have led to higher survey participation by those identifying as neuropsychiatrists. However, the survey respondents included 58% of all living dual-boarded neurologist-psychiatrists, and the high value they place on their dual training was remarkably consistent.

The absence of a reference group makes it difficult to conclude with certainty that the dual-trained neuropsychiatrists surveyed have opinions that differ from those of a similar group of general psychiatrists. These data, however, are consistent with the findings of Summergrad et al. from their 2008 survey that compared dual-boarded psychiatrists with single-boarded psychiatrists. Another limitation is inherent in the small number of active combined neuropsychiatry residency programs and the resulting small number of residents surveyed. The 18 respondents in combined neuropsychiatry residency programs at the time of the survey comprised 100% of combined neuropsychiatry residents in the United States. In the absence of published data, analysis of the reasons for fluctuations in the number of combined neuropsychiatry programs is based on the author’s 28 years of experience as a psychiatry and combined neuropsychiatry program director, his experience in the leadership of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatry Residency Training and its Combined Training Caucus, his leadership in ANPA and its Education Committee, and his experience on the ABPN Alternative Pathways Oversight Committee.

Conclusions

The popularity of dual residency training in neurology and psychiatry has been strongly influenced by the ABPN throughout the history of that organization. Since its inception in 2014, the ABPN Alternative Pathways Oversight Committee has assured that the curricula of combined residency programs in neurology and psychiatry include all required elements of both host disciplines. Dual-trained neuropsychiatrists take on a high degree of academic and leadership activity, treat conditions their single-specialty colleagues do not, have a high degree of career satisfaction, and feel less susceptible to burnout. Despite the growing availability of neuroscience-based advances in the diagnosis and management of brain disorders, the number of active combined neurology-psychiatry programs has remained constant for a number of reasons, including the complex environment of health care financing. Residents in training and graduates of combined neurology-psychiatry residency programs remain extremely positive about the benefits of their dual training.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the staff of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology for their kind assistance in obtaining historical data.