Abnormalities in the reward system are believed to play a role in many psychiatric disorders (for example, substance abuse, pathological gambling, major depression, schizophrenia, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease), so understanding the functional neuroanatomy of reward is important in neuropsychiatry.

3,5 Reward is not a unitary concept. Major aspects include liking (e.g., pleasure, hedonia), wanting (e.g., motivation for reward, incentive salience), and learning (e.g., past experiences predicting future rewards).

6 Primary (fundamental) rewards are naturally-occurring things or events that are essential for species survival and reproduction (e.g., food, sex). Secondary (higher-order) rewards are more abstract cognitive representations (e.g., monetary, artistic, altruistic, transcendent).

3,6 This review will focus on the contributions of the dopamine (DA) system to reward. Many other neurotransmitter systems also participate in aspects of reward.

7–9Reward

Research on brain areas important for reward began with the observation by Olds and Milner in the 1950s that rats will expend great effort in order to obtain electrical stimulation of multiple brain areas, including small regions within the brainstem, diencephalon, and cortex.

3,4,10–13 This work was foreshadowed by earlier studies in patients with schizophrenia that focused on the septal area, in which positive immediate responses (e.g., euphoria) were reported to occur after brain stimulation.

14The medial forebrain bundle in the lateral hypothalamus was a common target for electrode placement in animal studies, as stimulation in this area evoked very robust behaviors (e.g., self-stimulation to the point of physical exhaustion, willingness run across an aversive shock grid to obtain stimulation).

4,11–13 Several lines of evidence suggested that rewarding electrical stimulation activated the dopamine (DA) projection from the ventral tegmental area (via the medial forebrain bundle) to nucleus accumbens, one part of what is now termed the ventral striatum.

10,15 The ability of DA antagonists to decrease the effectiveness of rewarding electrical stimulation was particularly important. Subsequent studies indicated that the rewarding effect was not due to activation of the small, unmyelinated ascending DA fibers, but, rather, to large, myelinated fibers descending to brainstem.

10,11,13Animal studies indicate that brainstem DA neurons have a baseline level of activity (tonic mode, steady activation) that enables normal downstream functioning and is modulated by both positive and negative reward-related events (phasic mode, fast activation).

12,16–20 DA neurons increase activity in response to unexpected rewards and to stimuli that predict receipt of a reward (expectation or anticipation). During conditioned-learning, the increased activity in DA neurons shifts from the time of reward-receipt to the time of the reward-predicting stimulus. Activity is only increased by rewards if they are greater than predicted (positive prediction error). DA neurons also decrease activity when reward-expectation is not met (negative prediction error). If receipt of a reward is delayed, activity in these neurons decreases at the time the reward was expected, but did not occur, and increases when the reward is actually received. Much of behavior is guided by prediction of the future, based on past experiences. Phasic changes in DA activity, by signaling that something unexpected relating to reward has occurred, help to optimize goal-directed behavior. DA neurons also are sometimes responsive to other types of stimuli (e.g., stressful, aversive, alerting), perhaps because of their motivational salience. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies in humans have confirmed increased activation in the area of brainstem containing DA neurons during anticipation of both primary and secondary rewards.

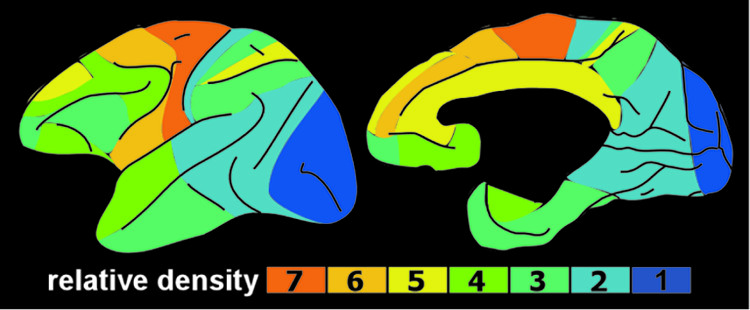

4Early studies suggested three distinct ascending DA projection systems from the brainstem (

Figure 1). Originally, it was thought that the limbic and cortical projections arose from the ventral tegmental area, with the substantia nigra giving rise to the projection to sensorimotor striatum (caudate and putamen); hence, the nigrostriatal name for this tract. It is now clear that, although the pathways are anatomically and functionally distinct, their cells of origin are intermixed.

4,21,22Two of these DA pathways are particularly important for the reward system.

3,4 The mesocortical DA pathway projects to multiple cortical areas and is important for many aspects of reward-processing, including hedonic evaluation, comparative valuation, and option-assessment. This pathway projects primarily to prefrontal, cingulate, and entorhinal cortices in rodents, but to the entire cortical mantle in primates (

Figure 2).

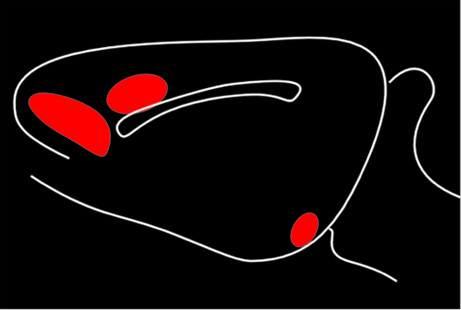

1,2,21,22 The mesolimbic DA pathway projects primarily to the ventral striatum, but, also, to other limbic areas (e.g., amygdala, olfactory tubercle, septum).

21 This pathway is important for the positive reinforcing effects of both natural rewards and drugs of abuse.

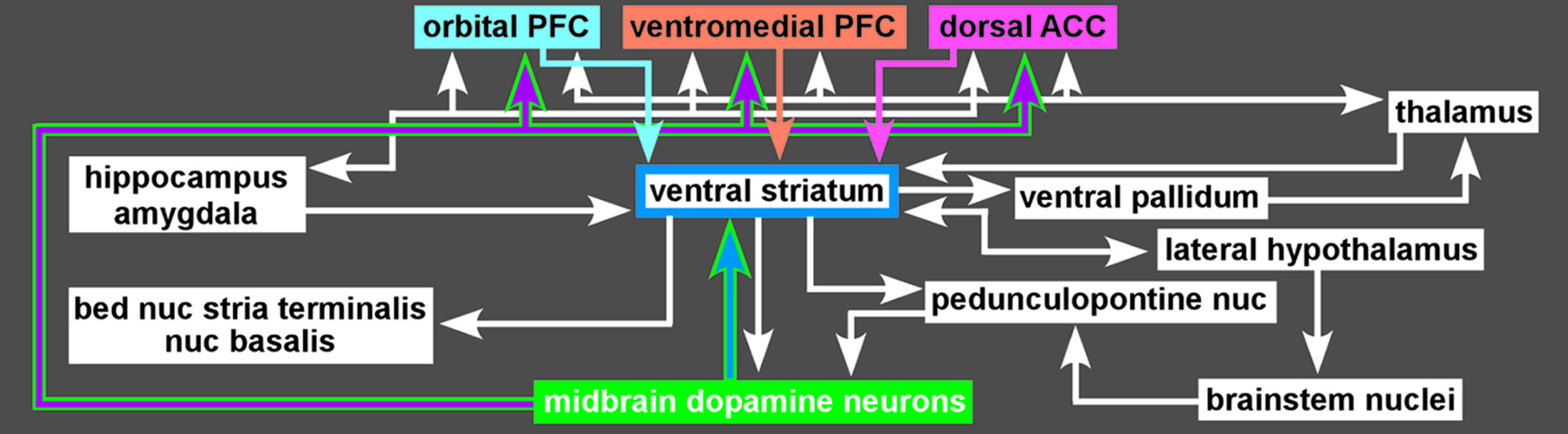

4 Ventral striatum also receives strong projections from orbitofrontal, ventral medial prefrontal, and anterior cingulate cortices, as well as limbic-related subcortical areas (

Figure 3).

4Functional imaging in humans has shown that rewards increase DA release in ventral striatum and that increasing striatal DA (by amphetamine administration) enhances rewards.

4,23 Activation in ventral striatum is more strongly associated with the anticipation of reward than the actual receipt, and activation level correlates with the magnitude of the expected reward and with the effort expended to gain the reward.

4,20,23 Some studies have reported decreased activation in ventral striatum when an expected reward is not received (reward prediction error).

4,20 The ventral striatum contains multiple functional areas, and it is quite possible that different aspects of reward are associated with specific subregions.

Although a valuable approach, most of the studies utilizing electrical stimulation were not designed to address which aspects of reward (liking, wanting, and learning) were involved.

24 The development of methods that allowed intracranial drug self-administration made it possible to more clearly identify regions participating in reward and to determine the nature of the influence (studies done primarily in rodents).

6,11 Areas of the brain that endow a sensation (e.g., sweetness) with hedonic value (pleasure or liking) are generally identified by their ability to enhance liking of sensory rewards when stimulated.

6 Areas presently believed to contain “hedonic hotspots” include both ventral striatum and ventral pallidum, brainstem (e.g., ventral tegmental area, parabrachial nucleus), and frontal cortex (e.g., orbitofrontal, cingulate, medial prefrontal and insular cortices). Some of these same areas are also important for endowing a sensation with motivational value (incentive-salience or wanting). The nature of the stimulation is important. Thus, there are areas within ventral striatum that evoke both liking and wanting when activated by opioids, but only wanting when activated by DA.

25 Recent studies suggest that DA is very important for the motivational value of rewards.

24Addiction

The economic costs (direct and indirect) of drug abuse are immense, estimated at $180.9 billion for the United States in 2002 alone.

26 Addiction to various substances is found across cultures worldwide, and animals will voluntarily self-administer drugs-of-addiction in laboratory settings.

12,13 Within the last decade, it has been recognized that behavioral addictions (e.g., gambling, pathological internet use, food) share the same core features as substance addictions. These include craving, tolerance, withdrawal, and compulsive use, despite occupational, interpersonal, and financial adversity. Although pathological levels of motivation (incentive-salience theory), learned compulsive behaviors (learning theory, habit theory), and avoidance of the negative aspects of withdrawal (negative reinforcement theory, opponent process theory) are likely all involved, the role each plays in the development and maintenance of addictions is a matter of much debate.

12,23,27A three-stage cycle (binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative emotional state, preoccupation/anticipation) has been proposed, in which a shift from impulsive to compulsive behaviors occurs as addiction develops.

12,13 From a neurobiological standpoint, addiction is a disorder of brain reward mechanisms that are crucial for survival.

9,12,13,23,28–30 Although the reinforcing value of drugs and the development of addiction involve multiple areas and neurotransmitter systems that differ by drug-of-abuse, the DA system is of central importance to all. The mesolimbic DA system is activated by all major drugs of abuse, with the ventral striatum a key structure. In animal studies, the brain stimulation required for reward (reward threshold) is reduced by acute administration of drugs of abuse. Activation in the ventral striatum is thought to be important in the reward-driven binge/intoxication stage, with engagement of dorsal striatum for the habit-formation that is believed to underlie progression to compulsive use. It has been proposed that drugs-of-abuse induce larger and more prolonged activations than natural stimuli, promoting habit-formation that is quite robust and resistant to change. Intrinsically below-normal functioning in the DA system has been proposed as a risk factor for development of addiction (reward-deficiency hypothesis). Reward thresholds increase (sensitivity to rewards decrease) during protracted withdrawal after chronic drug administration, suggesting compromise of the DA system. The anhedonia and motivational deficits present during the withdrawal/negative emotional state stage may be due to decreased DA function (reward-deficiency). It has been proposed that continued drug use at this stage is more to restore a normal DA level to (“get straight”) than to evoke a large DA increase to (“get high”). Alterations in the brain's stress systems also occur, and may be important for aversive stimulus effects and/or heightened anxiety. Altered activity in areas of prefrontal cortex and perturbations in their modulation of limbic-related subcortical areas (particularly ventral striatum, amygdala, and hippocampus) are present in the preoccupation/anticipation stage and may give rise to the deficits in executive functions (e.g., self-control, salience-attribution), and memory commonly present in addiction.