An intensive reanalysis of a subsample of the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) reinforces the central role of combat trauma for the onset of posttraumatic stress symptoms but also finds complex interactions between that experience, prewar vulnerabilities, and causing harm to civilians or enemy prisoners.

The relative significance of combat and prior vulnerabilities has sparked debate for years, noted Bruce Dohrenwend, Ph.D., a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and a professor of psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia. The study by Dohrenwend and colleagues appeared online February 15 in Clinical Psychological Science.

Combat exposure is more important than vulnerability factors in the onset of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but vulnerability factors have a greater influence on the persistence of the disorder over time, they concluded. In addition, soldiers who harmed civilians or prisoners faced increased risk for PTSD.

“This is the first study to bring together these three factors,” John Fairbank, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, told Psychiatric News. Fairbank worked on the original NVVRS study, but was not involved with the current reanalysis. “It adds to the growing literature over the last decade showing that there’s a complex interaction, and an additive effect, of risk factors.”

The NVVRS studied 1,200 men in 1986 and 1987 who had served in Vietnam from 1965 to 1975. The current study covered a subsample of 248 men who had received a diagnostic examination using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Measures of combat exposure were based on both unit military records and personal self-report, covering life-threatening experiences, witnessing the death of a friend, and killing enemy personnel. The men were also asked about involvement in harming or killing Vietnamese civilians or prisoners.

Dose-Dependent Effect Found

Dohrenwend and colleagues found that 32 percent of the veterans who experienced SCID Criterion A combat stressors developed PTSD symptom syndrome (PSS)—the co-occurrence of intrusive, avoidance/numbing, and arousal symptoms for at least one month.

The researchers distinguished between PTSD and PSS in order to “assess the presence or absence of PSS independently of the presence of Criterion A as stressors that are needed for the full PTSD analysis.”

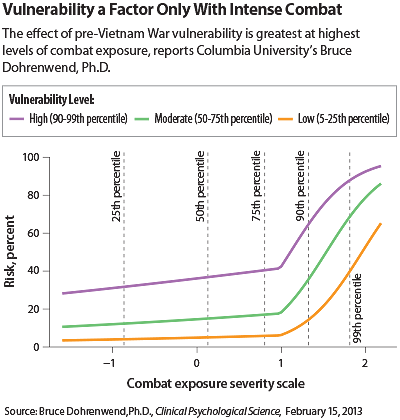

The effect of combat was dose dependent. Veterans with very severe combat exposure had an increasingly higher likelihood of both onset and current (prior six months in 1986-1987) PSS.

“PSS can occur in individuals who show little personal vulnerability when stressor exposure is especially severe,” said the researchers. But that stressor was essential for development of posttraumatic symptoms: “[A]t most, 2 percent of the veterans had onsets of PSS in the absence of Criterion A.”

This leads Dohrenwend to support a narrow definition of Criterion A, limiting it to life-threatening stressors such as combat exposure, rape, or child abuse rather than less-severe stressors of daily life such as divorce or unemployment, as others have suggested.

Four prewar vulnerability factors were found to have the highest statistical risk for PTSD onset: childhood physical abuse (39 percent), conduct disorder (39 percent), pre-Vietnam psychiatric disorders (34 percent), and family members with arrest records (38 percent). Younger age was also a risk factor.

Harming Civilians Raises PTSD Risk

The researchers initially hypothesized an inverse relationship between vulnerability and posttraumatic stress—that more vulnerable soldiers would develop PTSD at lower combat thresholds.

But in fact, the more severe the soldier’s combat experience, the greater the effect of vulnerability was on the presence of current PSS. “[V]ulnerability makes a huge difference for those with the highest level of combat exposure,” they noted.

One way to reduce the prevalence of chronic disorders related to posttraumatic stress would be to avoid placing the more-vulnerable soldiers into the most-stressful combat settings, suggested Dohrenwend.

Finally, about 13 percent of respondents reported some personal involvement in harming civilians or prisoners, acts that sharply increased their likelihood of PSS onset.

“Almost two-thirds of the harmers (62 percent) had onset, compared with only 15 percent of the nonharmers,” said the authors. A dozen years after the war, 40 percent of the harmers had PTSD versus 6 percent of the nonharmers. Harming was more strongly associated with combat exposure than with vulnerability.

The three factors had a strong additive effect. The combination of high combat severity, high vulnerability, and harming produced a 97 percent chance of PSS onset.

“This study underscores that the onset and longitudinal course of PTSD is complex,” said Fairbank.

The lessons of a war four decades in the past may offer insights into present conflicts. For U.S. forces, the Vietnam War was a “war amongst the people,” concluded Dohrenwend and colleagues. “So, more recently, have been the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

“When the original NVVRS study was completed in 1986-88, people were barely aware of PTSD,” recalled Fairbank. “Now PTSD is part of everyday language. The country as a whole is more attentive to how men and women who have served [in the military] are doing, in both physical and psychological well-being.” ■