Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and six other medical centers say that contrary to previous findings, medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) do not counter the risk for substance use and abuse among teenagers.

The study’s lead author, Brooke Molina, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and colleagues said theirs is the first study to examine teenage substance abuse and treatment for ADHD in a large multisite sample and the first to recognize that increased use of cigarettes in teenagers with ADHD histories commonly occurs with use of other substances such as alcohol and marijuana. Their findings are published in the March Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The study participants were the nearly 600 youngsters in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA), who were recruited in childhood, treated for ADHD for 14 months in a randomized clinical trial, and then followed up with substance use assessments through adolescence. Although the first published MTA report of substance use at the three-year mark (when participants were aged 10 to 13) showed no protective or predisposing associations between substance use and medication, the current study details the eight-year follow-up, when the participants were at a mean age of 16.8.

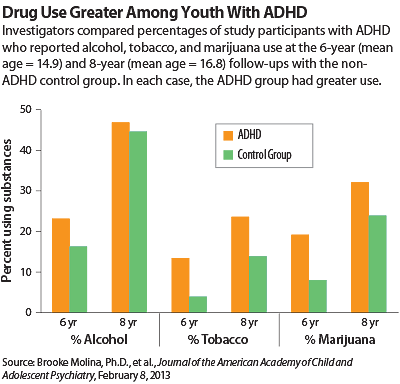

And this time, the results were different. They found a significantly higher prevalence of substance abuse and cigarette use by adolescents with ADHD histories than by those without ADHD.

Among the findings:

When the adolescents were an average of 15 years old, 35 percent of those with ADHD histories reported using one or more substances, compared with only 20 percent of their peers without ADHD histories.

Ten percent of those with ADHD met criteria for a substance abuse or dependence disorder, which means they experienced significant problems from their substance use; only 3 percent of the non-ADHD group did.

When the adolescents were an average age of 17, marijuana was especially problematic, with 13 percent versus 7 percent of the ADHD and non-ADHD groups, respectively, indicating marijuana abuse or dependence.

Daily cigarette smoking was very high at 17 percent in the ADHD group; the smoking rate of non-ADHD teens was only 8 percent.

Alcohol use was high in both groups, highlighting its common occurrence in teenagers

Substance abuse rates did not differ between children who were still being treated with ADHD medication and those who were not. Cumultive stimulant treatment also had no effect on rates.

“This study underscores the significance of the substance abuse risk for both boys and girls with childhood ADHD,” said Molina, in a statement coinciding with the study’s publication. “These findings also are the strongest test to date of the association between medication for ADHD and teenage substance abuse.”

The authors noted in particular the finding that substance abuse rates were the same in teens still taking ADHD medication and those no longer doing so and said that their findings point to a need to identify alternative approaches to substance abuse prevention and treatment for youth with ADHD.

“We are working hard to understand the reasons why children with ADHD have increased risk of drug abuse. Our hypotheses, partly supported by our research and that of others, is that impulsive decision making, poor school performance, and difficulty making healthy friendships all contribute,” Molina said.

“Some of this is biologically driven, because we know that ADHD runs in families. However, similar to managing high blood pressure or obesity, there are nonmedical things we can do to decrease the risk of a bad outcome. As researchers and practitioners, we need to do a better job of helping parents and schools address these risk factors that are so common for children with ADHD.”

In an editorial accompanying the study, Benjamin Goldstein, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry, pharmacology, and toxicology at the University of Toronto and director of the Youth Bipolar Disorder Program at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto, agreed that this new information is useful, if not definitive. “Based on the extant literature—bolstered by the current study—it would be inaccurate to characterize stimulants as a globally effective inoculation against substance misuse,” he said. “Nonetheless, it remains likely that there is a subset of youth for whom ongoing stimulant treatment may prevent the academic impairment, peer difficulties, family conflict, and impulsive decisions that plant the seeds of substance misuse.”

Commenting on the study for Psychiatric News, child and adolescent psychiatrist David Fassler, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont and treasurer of APA, said, “Consistent with previous findings, the authors report that ADHD was associated with an increased risk of substance use and substance use disorders in this age group; however, the prevalence was neither increased nor decreased as a result of treatment with medication. This result challenges the widely held belief that early and appropriate treatment of ADHD will reduce the risk of substance use during adolescence. As the authors noted, the finding underscores the importance of identifying effective approaches to the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders in adolescents with ADHD.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse. ■

An abstract of “Adolescent Substance Use in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (MTA) as a Function of Childhood ADHD, Random Assignment to Childhood Treatments, and Subsequent Medication” is posted at

http://www.jaacap.com/article/S0890-8567(12)01000-3/abstract.