Clinical observation of behavior and evaluation of certain minor physical anomalies serve to diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but both diagnosis and treatment might be made more precise with better insight into the underlying genetics of each individual’s version of the disorder.

One new study takes another step in that direction by combining two different ways of probing the genome.

A team of researchers studied 258 children from Labrador and Newfoundland who were previously diagnosed clinically with ASD. Some had minor physical anomalies, “slight morphological deviations present in less than 5 percent of the normal population,” according to Kristiina Tammimies, Ph.D., of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, and colleagues, writing in JAMA September 1. Sometimes a dysmorphology can identify a specific syndrome, but it usually functions as a clue that something else is going on that requires investigation.

The children also were given magnetic resonance brain imaging scans to look for structural brain abnormalities. From that information, the researchers created a total morphological score, dividing the cohort into “essential” (that is, with few anomalies), “complex” (with many anomalies), or “equivocal” (in between) ASD groups.

“The premise … is that individuals for whom there is evidence of an insult to early morphogenesis would have developed their autism on a different basis than individuals for whom morphogenesis proceeded normally,” wrote Judith Miles, M.D., Ph.D., a professor emerita of child health and genetics at the University of Missouri in Columbia, in an accompanying editorial.

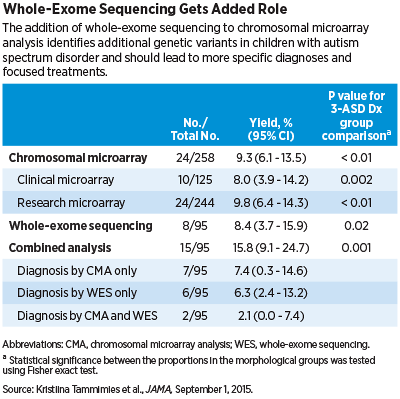

Finally, each child received two genetic tests: chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and whole-exome sequencing (WES). CMA identifies copy number variants (duplicated or deleted lengths of DNA), and WES identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms.

CMA has been in use for some time, and the American Academy of Genetics recommends its use for all children diagnosed with ASD. The test is usually reimbursed by insurance companies because it yields meaningful information, said Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, who was not involved with the study. WES has been used so far as a research tool. “But here, it adds information above and beyond the CMA.”

The CMA alone revealed that the complex ASD group had a higher proportion of pathologic CNVs (24.5 percent) than the essential group (4.2 percent). For WES, the rates for probands with a molecular diagnosis were 16.7 percent in the complex group and 3.1 percent in the essential group. Using both methods, the combined yield of molecular diagnoses was significantly higher in the complex group than the essential group.

“A combined molecular diagnostic yield of 15.8 percent was found in those children who received both tests,” wrote Tammimies. That more than triples the yield relative to results a decade ago. “Our study illustrates the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of ASD.”

The costs of such genetic tests are coming down, said Veenstra-VanderWeele. The CMA now costs about $300 to $500 per test, and the WES is down to $1,000 per test in research projects.

Even now, existing genetic tests can be helpful for the families of patients with ASD, both for guiding treatment decisions and for other reasons, said Veenstra-VanderWeele.

“Also, if the mutation is inherited from the parents, they can make decisions about family planning,” said Veenstra-VanderWeele. “And you can’t underestimate the value to the family of providing a reason for ASD or suggesting potential avenues to treatments.”

The study of one mutation, for instance, led to hypotheses about dietary adjustments for patients with ASD. Those changes were tested in mice and then in patients and found to ameliorate symptoms.

“It seems possible that it will not be too long before the evidence presented by Tammimies et al will prompt a … recommendation to include whole-exome DNA sequencing as a first-tier ASD test, if not for all ASD diagnoses, certainly for children with physical dysmorphology,” concluded Miles. ■

“Molecular Diagnostic Yield of Chromosomal Microarray Analysis and Whole-Exome Sequencing in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder” can be accessed

here. “Complex Autism Spectrum Disorders and Cutting-Edge Molecular Diagnostic Tests” is available

here.