Robots are becoming more and more ubiquitous in the medical arena, helping their human companions perform surgeries, diagnose disease, and even dispense medication.

Of the many medical disciplines, one might think that psychiatry—a field that emphasizes human interaction and empathy—would be more resistant to the robot revolution. Yet, while still nascent as an application, robotic therapy is coming into its own in the mental health arena.

One of the most vibrant areas of research involves robots to help children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

“There have been fairly consistent findings that kids with autism show a preference for interacting with technology compared with other people,” said Zachary Warren, Ph.D., an associate professor of pediatrics, psychiatry, and special education at Vanderbilt University. “So the question is how do we use this preference to boost early social skills, as opposed to having technology exacerbate their deficits in social behavior?”

At Vanderbilt’s Kennedy Center Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders (TRIAD), Warren has been working with engineering colleagues to develop an intelligent learning environment where he can test a robot’s ability to help children learn joint attention—the ability for two people to share focus on a common item.

Children typically learn the elements of joint attention within the first couple of years of life, and impairments in this trait are one of several early telltale signs of ASD.

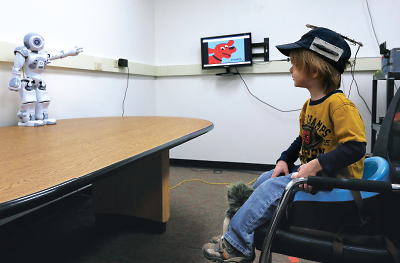

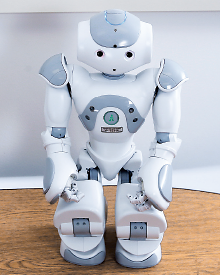

Warren’s environment makes use of a system of cameras that can track the head movements of a child (by means of a sensor-outfitted hat) to see where his or her attention is focused. At the center of this room is a small humanoid robot that interacts with the child and provides prompts, such as verbal commands or pointing, to guide their gaze to specific locations, for example a video monitor showing a video of the child’s caregiver.

If a child doesn’t respond to one prompt, the robot can switch to another tactic or combine multiple elements to find the best approach to meet the needs of each child. After any successful prompt, the robot also reinforces the child with positive praise.

While other technological interventions such as a screen-based teaching program might help with joint attention or other early-age skills, Maja Matarić, the Chan Soon-Shiong Professor of Computer Science, Neuroscience, and Pediatrics at the University of Southern California, notes that robots provide a unique advantage.

“We engage differently with physical creatures than we do with images on a screen,” she told Psychiatric News. “And a robot offers that physical embodiment that lets it transcend from being just a tool to a peer caregiver.”

By peer, Matarić noted she does not mean that she believes that a robot could replace a human companion—a concern that she and other robotics researchers see as a baseless cause of concern. “Human care is extremely sophisticated and irreplaceable,” she said. “But a robot can complement human interaction and be a friend, or a nurse, or a coach for all those hours when a therapist or caregiver is not providing attention.”

The latter role is one of significant interest in Matarić’s research program, as she has been exploring robots’ ability to teach ASD children to carry out simple instructions as a way to learn autonomy.

Much like Warren’s model, these robots adapt to the children they work with and teach actions through graded cuing; the robot will first provide verbal instructions—for example to copy the robot’s pose—and if the child doesn’t respond, the robot begins providing progressively more detailed instructions or physical cues.

Robots are ideally suited to providing such lessons, according to Elaine Short, a Ph.D. student in Matarić’s lab. “Robots may be simple, but they don’t judge you, and they don’t lose patience, but they can still provide a feeling of social support,” she said.

Short is working on a project where she is testing the ability of a robot to encourage social interaction among children with ASD during free play. With the robot serving as a focal point, Short suspects that children may be more willing to open up and begin socializing.

Costs Still a Factor, but the Field Is Fertile

Using socially adaptive robots in a group-like setting might be something that could happen in educational systems or clinics in the near future, and Warren doesn’t discount that household robots could be commonplace.

“People believe robots would be quite expensive, but as with other technologies, robotics is advancing rapidly in terms of higher scale and lower cost,” he told Psychiatric News.

Some of Warren’s research tools are already in millions of homes, as he has been looking at using Kinect products (a line of motion sensing devices developed by Microsoft for use in video games) to make the learning environment even more interactive by enabling the child to guide the robot.

“And comparatively speaking, it is not that financially prohibitive. I recently posited that the cost of a trial of our interactive environment using 40 children would be less than one year of behavioral therapy for one child with autism.”

Even so, getting sufficient support can be daunting. “Funding agencies have traditionally been conservative about funding social sciences and conservative about funding technology projects, so when you try and put them together, well, there will be some biases,” Matarić said.

In addition, showing that these pilot projects are successful is a tricky proposition. ASD is a complex and heterogeneous disorder, and Matarić pointed out that the whole purpose of adaptive robots is to personalize them to individual children to take that heterogeneity into account. “How do you prove a personalized technology in a comparative study?” she asked.

Despite these concerns, social robotics is a fertile field with a small, but talented pool of researchers working on bringing it to clinical fruition, with the help of open-minded mental health practitioners providing their expertise.

And the applications can go well beyond early-age social behaviors. Warren and his colleagues at TRIAD, for example, are working on an interactive gaze-based platform that will help teach adolescents with ASD another crucial skill—how to drive.

Matarić, meanwhile, sees the potential for robots to provide therapy for children with a host of developmental problems. Children who have experienced abuse or trauma would be one especially worthwhile group to study, as they would be more likely to open up to a robot rather than a person, she noted as one example.

At the other end of the age spectrum, social robots might offer some cognitive benefits to older adults with Alzheimer’s or other dementia through socially stimulating tasks.

“Every human situation is unique, but socially assistive robots target a common fundamental part of human nature,” she explained. “How do you motivate people? How do you engage people?”

In many cases, it might take a concerted effort of man and machine. ■