While it is no secret that mental illness places a huge economic burden on the United States, a new analysis of national medical spending trends between 1996 and 2013 provides a stark picture of the impact of psychiatric problems compared with other medical conditions.

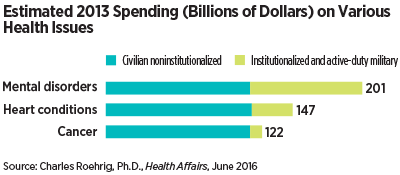

The study, published online May 18 in Health Affairs, found that mental disorders accounted for an estimated $201 billion in direct health care costs in 2013, representing nearly one-tenth of all medical spending that year. Heart conditions and trauma, which came in second and third, accounted for $147 billion and $143 billion, respectively.

In 1996, mental disorders were second costliest at $79 billion, trailing heart conditions, which accounted for $105 billion in spending.

Of the $200 billion in costs, more than 40 percent came from outside the general civilian population, a group that includes nursing community residents, psychiatric hospital inpatients, prisoners, and active-duty military; no other medical category had such a large chunk of spending derived from this category of institutionalized civilians and active military.

Charles Roehrig, Ph.D., the founding director of the Center for Sustainable Health Spending at Altarum Institute in Michigan and author of the spending analysis, noted that other estimates of medical spending, such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), do not include this subpopulation and their financial impact.

However, the driving force of these costs might surprise some. “People might naturally think that the increased spending is due to the rise of Alzheimer’s and other dementia cases as our population ages,” Roehrig told Psychiatric News. “But that was not the case.”

He pointed out that spending on dementia care rose only an average of 4 percent annually in the analysis period (1996 to 2013)—slightly below the 4.3 percent annual growth of the United States gross domestic product (GDP) in that same period. Rather, spending for depression and anxiety, which grew at over 7 percent annually from 1996 to 2013, was responsible for much of the increase.

The future, though, could be a different story. “In 2013, only the oldest baby boomers had become eligible for Medicare, which means an influx of people ready to enter into the category of institutionalized civilians is looming,” Roehrig said. “And as of yet no one has reached the threshold of curing diseases of the very elderly, so there is an urgent need to think proactively about managing costs.”

APA President Maria A. Oquendo, M.D., agreed with this assessment. “The fact that more than 40 percent is spent on populations in prisons, nursing homes, and other institutional settings demonstrates the need to invest more in preventive mental health care,” she told Psychiatric News.

As an example, she noted that spending for heart conditions increased by only 2 percent annually from 1996 to 2013, which the study attributed in part to increased prevention measures, such as a reduction in smoking and more awareness and treatment of risk factors like high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

“However, while noninstitutional mental health care is significantly less expensive, this study should not be misread to mean we need to invest less in outpatient settings,” Oquendo added. “The reality is that we need to spend wisely on all fronts.”

Roehrig noted that these spending estimates do not account for all medically related costs; there was insufficient data for three categories of expenses (durable medical equipment, nondurable medical products, and other personal health care) totaling around $274 billion to allocate them among the various medical conditions and thus were not included in the analysis.

The study was funded by the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. ■

An abstract of “Mental Disorders Top the List of the Most Costly Conditions in the United States: $201 Billion” can be accessed

here.