Antipsychotic medications that act on the dopamine D2 receptor have been around for decades, yet the details of how these drugs interact with the receptor have remained mysterious. Having a detailed picture of receptor binding sites can help researchers design drugs that interact in just the right way to optimize the therapeutic effect and limit unwanted side effects.

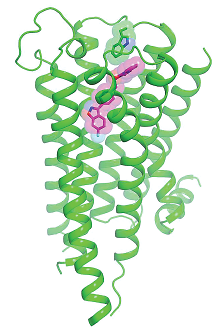

Earlier this year, a team of researchers announced they had solved the 3-D structure of the D2 receptor bound with risperidone. This discovery, which was outlined in an article in Nature, could provide a breakthrough in the search for new antipsychotics.

The publication of this 3-D structure also represents the conclusion of a long journey for lead investigator Bryan Roth, M.D., Ph.D., the Michael Hooker Distinguished Professor of Protein Therapeutics and Translational Proteomics at the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine.

Roth and his lab have been attempting to solve the structure of D2 for over a decade. He estimates that over this time his group created over 300 differently engineered (chemically tweaked) versions of the D2 receptor and used 30 different drugs as the binding partner. The goal of this trial-and-error process was to find a combination that would allow the receptors to form into ordered crystals (the process of forming protein crystals is similar to that used to form salt crystals, though protein crystals are much more delicate, and getting crystals of good quality is difficult).

The labor of love finally paid off, and the result shows that risperidone—and likely other atypical antipsychotics—bind to D2 in an unusual way compared with what is known about other dopamine receptor ligands. (While Roth was the first to solve the D2 structure, the structures of other dopamine receptors have been previously identified.)

As Roth explained, if you hold out your hand parallel to the floor and then slowly lower it, that reflects how most drugs bind to a dopamine receptor. “Now, tilt your hand so it is perpendicular to the floor, fingers down; that’s how risperidone wedges in—straight and deep into the receptor pocket,” Roth said. In another unexpected feature of D2 binding, some parts of the risperidone molecule bend and twist once joined with the D2 receptor, Roth noted.

The fit is not perfect; the structure revealed some gaps in the binding area. The researchers also discovered that some of the key regions that hold the risperidone molecule are similar in their amino acid composition to sections of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, which may explain why risperidone shows an affinity for this class of receptors as well, Roth added.

“We now know why risperidone does not exclusively bind to the D2 receptor,” Roth said. “And with that knowledge we can create drugs that are way more selective.”

Roth recently collaborated on a drug project that used structural information on the mu-opioid receptor to develop a potentially nonaddictive opioid-based analgesic (

Psychiatric News, October 7, 2016), and he is optimistic that this D2 structure can yield similar results—an antipsychotic with minimal side effects.

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health. ■