Numerous clinical studies have shown that early psychosis programs are effective at helping people who are experiencing psychosis for the first time to manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life. Less is known about how well these programs work for a large population once they are implemented within the broader health care system.

A study published March 2 in AJP in Advance has now taken a closer look at health service use and health outcomes among patients who used one such established early psychosis program in the greater London, Ontario, region called the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychoses (PEPP). Analyzing health data from a 17-year period, the investigators found that people who used PEPP services had more frequent contact with psychiatrists and substantially lower rates of mortality during their first two years in the program than people who did not use these services.

The findings add to the growing evidence of the value of early psychosis intervention (EPI) services to connect patients with care and improve health outcomes.

For the study, Kelly K. Anderson, Ph.D., of the University of Western Ontario and colleagues analyzed health administrative data from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which captures all medical visits covered under the universal Ontario Health Insurance Program. The researchers compared various health outcomes (such as self-harm, suicide, and all-cause mortality) and use of health services (including primary care, outpatient psychiatry, emergency department, and inpatient hospitalizations) in 530 people who were using EPI services between 1997 and 2013 with 922 matched controls who were not using these services.

The authors found that in the first two years following admission, EPI service users were six times more likely to have had contact with a psychiatrist and reached out to a psychiatrist more quickly (an average of 13 days after admission compared with 78 days for EPI nonusers). EPI service users were also less likely to visit a primary care physician or the emergency department, but they were more likely to be hospitalized.

Anderson told Psychiatric News that when she and her colleagues looked closer at the data, they saw that EPI service users were less likely to be involuntarily admitted to the hospital. She noted that patients who voluntarily arrive at an inpatient setting tend to have shorter stays and a lower risk of rehospitalization. “These findings can therefore be seen as a positive in a real-world system with constrained resources,” Anderson said. “London, like many places, has a shortage of inpatient units.”

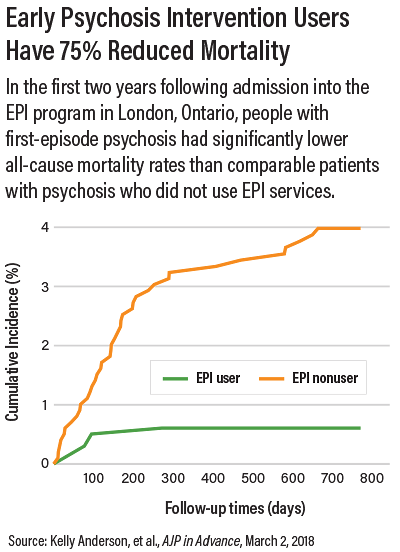

The increased use of inpatient services may have also contributed to the roughly 75 percent lower rate of all-cause mortality among EPI service users after two years compared with nonusers. There were no differences between the two groups in rates of self-harm or suicide; however, the total number of self-harm events in both groups was small.

“[M]any of the observed benefits did not persist in the period from two to five years postadmission, when care is typically stepped down to medical management,” Anderson and colleagues wrote. “These changes in patterns of service use are likely a consequence of both reductions in the intensity of EPI services and improvements in the clinical status of nonusers, due to the natural trajectory of psychosis.”

Anderson added, “A major theme of EPI research today is trying to find the optimal duration of intervention. Our findings provide some evidence that a longer duration of intensive care would lead to improved health outcomes.”

This study was supported by a New Investigator Fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation. ■

“Effectiveness of Early Psychosis Intervention: Comparison of Service Users and Nonusers in Population-Based Health Administrative Data” can be accessed

here.