“[W]hatever one may come to consider a truly American trait can be shown to have its equally characteristic opposite. … Most of her inhabitants are faced in their own lives … with alternatives presented by such polarities as open roads of immigration and jealous islands of tradition, outgoing internationalism and defiant isolationism, boisterous competition and self-effacing co-operation. …” —Erik Erikson, Childhood and Society

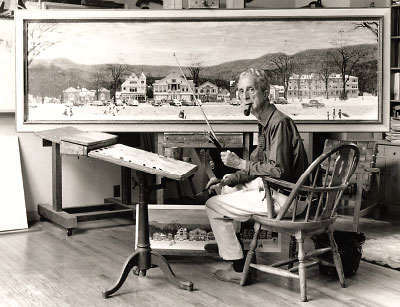

As America emerged from the Great Depression in the late 1930s and into the 1940s, the illustrations of Norman Rockwell reflected the country’s sense of itself—or how it wanted to see itself, whatever conflicts might have been roiling below the surface. In more than 140 covers for the Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell conjured up an American ideal: pastoral, communal, whimsical.

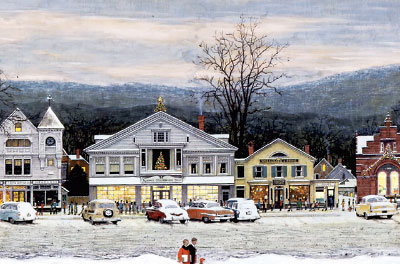

But there was trouble outside the picture frame, and Rockwell and his wife left rural Vermont in 1953 for Stockbridge, Mass., where his wife entered treatment for depression and alcoholism at the Austen Riggs Center, on the town’s Main Street. There, Rockwell encountered Erik Erikson, then a clinician at Riggs, who would become Rockwell’s own therapist.

A serendipitous encounter if ever there was one: the immigrant therapist who would become famous for articulating the importance of identity and the “identity crisis” and the illustrator whose drawings and paintings evoked an idealized American image. Erikson and Rockwell, their work and their relationship, may be especially resonant today in an America riven by questions about identity and inclusion and the twin epidemics of opioid overdose and suicide—“diseases of despair” rooted in pervasive loneliness, disintegrating community bonds, and lost identity.

A remarkable exhibit, “Inspired: Rockwell and Erik Erikson,” at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, coincided last month with the centennial anniversary of the Austen Riggs Center, celebrated during a two-day conference titled “The Mental Health Crisis in America: Recognizing Problems, Working Toward Solutions.”

A broad theme emerging from that conference was that Erikson’s vision of personal identity rooted in relationships within the broader community is especially meaningful today; and that the Riggs treatment model based on intensive psychodynamic psychotherapy embedded in an open, entirely voluntary therapeutic community has something decisive to offer when the reigning focus on short-term crisis stabilization exhausts itself in failure (see story

here).

“In the 1990s after the failure of the Clinton health care reform plan, there was rampant cost cutting by managed care,” Eric Plakun, M.D., medical director and CEO of Austen Riggs, said at the conference. “When managed care shifted the goal of treatment to mere crisis stabilization, there was a real question whether an institution like Riggs could survive. Under the leadership of Edward Shapiro [then medical director], we made a critical decision to remain true to our roots and our values. If we failed, we failed. If we survived, it would be because what we had to offer makes a difference.”

Riggs developed a continuum of care in response to the times, and it has survived and flourished. Plakun and others conference speakers acknowledged that what Austen Riggs offers is unusual in length and intensity of treatment, but the core values that have made the institution successful—patient authority, treatment that regards individuals as more than collections of symptoms, the importance of relationships, and a focus on understanding the meaning of symptoms—are “scalable,” capable of being translated to settings serving a broader public.

Erikson Seeks an Identity

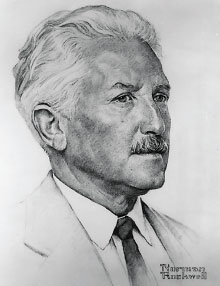

In paintings, photographs, and correspondence, the exhibit at the Rockwell Museum showcases the unique relationship that Erikson and the American illustrator shared. The exhibit includes portraits by Rockwell of Erikson (see image below) and other clinicians at Riggs housed within the larger collection that contains some of Rockwell’s most iconic works.

For visitors unfamiliar with Erikson, the exhibit offers an introduction to the unique contribution he made to psychoanalytic thinking and to work at Austen Riggs. “Erikson became an American cultural icon after he left Riggs to teach at Harvard,” Plakun told Psychiatric News. “He did much to launch the relationship between psychoanalytic thinking and the social sciences that persists today. Riggs’ Erikson Institute for Education and Research holds onto that synergistic relationship as part of its mission.

“But Erikson was an innovative clinician before that. His was one of the voices that moved psychoanalysis forward, out of the shadow of deference to Freud. He changed psychoanalysis when he shifted the focus from libido, sexual energy, and the intrapsychic toward recognition that an individual also lives in a social context—shifting the focus of psychoanalysis from the psychosexual to the psychosocial.

“Each person’s history is their own but inevitably shaped by the history of their time,” Plakun said.

Jane Tillman, Ph.D., director of the Erikson Institute, was a consultant and adviser in curating the exhibit. She said that Rockwell and his art, reflecting something quintessentially American, may have been especially attractive to the immigrant therapist who had his own personal reasons for anxiety about identity.

“Rockwell was eight years older than Erikson and well established in his fame as an illustrator by the time Erikson arrived in Stockbridge,” she said. “Erikson may have looked to Rockwell for how to navigate the strains of newfound acclaim. Erikson, who was born in Germany in 1902, had been named Erik Salomonsen at birth, but it was never clear who his father was—his paternity remained a mystery all of his life.”

Erikson’s mother remarried when he was 3, and young Erik was adopted by her new husband and became Erik Homburger. Erik and his Canadian wife, Joan, and child emigrated to the United States in 1933. At their naturalization ceremony in 1938, he took the name Erik Homburger Erikson. Later he simply was known as Erik H. Erikson, then just Erik Erikson.

“His wrestling with his identity began early in his life as he tried to find a name that made sense to him,” Tillman told Psychiatric News. “That Erikson coined the term ‘identity crisis’ is no surprise given his history.”

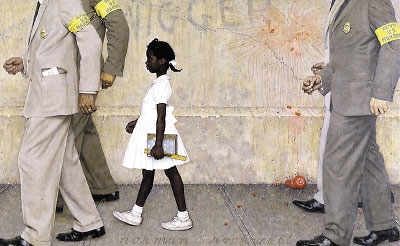

It was in the 1950s when Erikson became available as a consultant and therapist to Rockwell to help him understand some of the difficulties he faced in his family life. “This relationship was unusual by today’s standards as the exhibition shows that they also were in the same social circle and had a friendship,” Tillman said. It was during this period that Rockwell’s work—partly through Erikson’s encouragement—became more earnest, reflecting some of the social issues of the day, especially racial equality about which Rockwell was passionate.

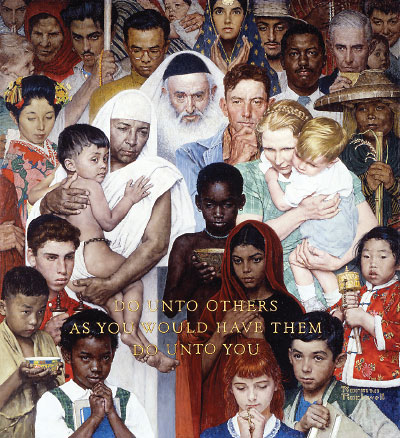

Another painting in the exhibit, Rockwell’s 1961 “Golden Rule,” reflects America’s varied ethnicities and religions. “This painting captures a time in history when America was more welcoming of immigrants and championed religious liberty, something we are in the process of losing,” Tillman said. “Erikson, as an immigrant, was always enormously grateful to be an American, and he had a great love for the welcome he felt in this country.”

Plakun added, “Erikson knew something about the danger of what he called ‘pseudospeciation’—the treating of a group of outsiders as if they were another species. This is how he came to understand how people who were Nazis could engage in genocide, and it has obvious links to where we are as a nation and a world around immigration and the rising reaction against those who are ‘other.’ ” ■

Psychiatric News thanks the Norman Rockwell Museum for its generous permission to reprint images.