People who die by suicide by violent means (such as the use of a firearm) show distinct biological signatures compared with those who die by suicide by nonviolent means (such as carbon monoxide poisoning), according to a report in the American Journal of Psychiatry. Using data from an extensive collection of human brain tissue, investigators at the Lieber Institute for Brain Development in Baltimore and colleagues identified different gene expression signatures in people who died by suicide by violent means compared with others who died.

“Suicides by violent means are distinct in that people usually don’t have time to change their mind; they are extreme behavioral acts that end precipitously,” said Daniel Weinberger, M.D., director and CEO of the Lieber Institute for Brain Development and senior author of the study. “Still, we were surprised at the extent of genetic differences this study uncovered.”

Weinberger and colleagues compared the gene expression profiles of 226 brain tissue samples from individuals with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder. Based on available information on the manner and circumstances of death, the researchers divided the samples into three groups: 77 individuals who died by suicide by violent means, 50 who died by suicide by nonviolent means, and 99 who did not die by suicide. As an additional comparison, the researchers included brain tissue samples from 103 individuals who did not have a psychiatric diagnosis and did not die by suicide (the researchers called this group the neurotypical group). The researchers focused their attention on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a brain region involved in higher cognitive functions, such as planning and decision-making.

“Suicide is a rarely accessible phenotype, so most research investigates patients who, thankfully, survived a previous suicidal attempt,” said lead study author Giovanna Punzi, M.D., Ph.D., a research scientist at the Lieber Institute. “But these brain samples might offer an exceptional ‘biological snapshot’ of what was going on during suicide completion.”

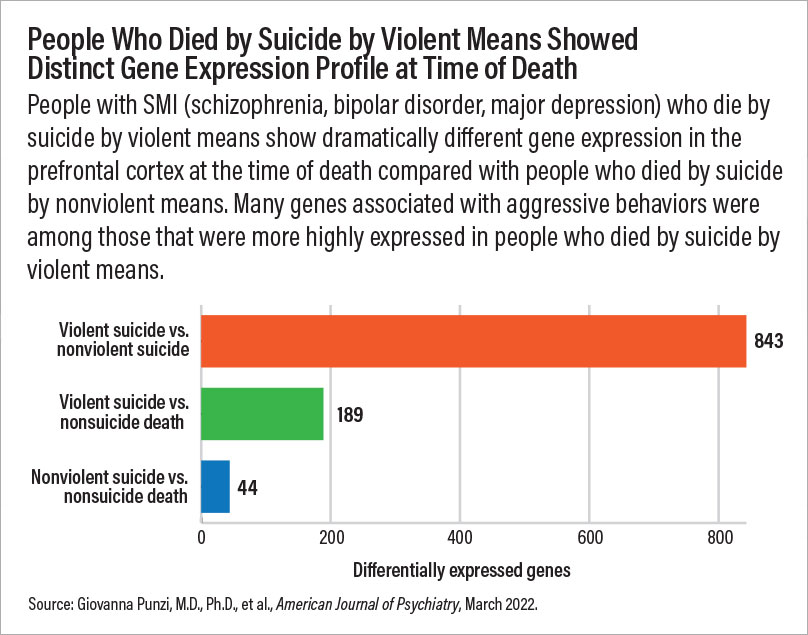

There were gene expression differences in all four groups, but the starkest difference was between people who died by violent suicide and those who died by nonviolent suicide: over 800 genes were differently expressed between these two groups. When comparing individuals who died by violent suicide with those with a psychiatric diagnosis who did not die by suicide, the researchers found variation in gene expression in 189 genes. When comparing individuals who died by nonviolent suicide with those with a psychiatric diagnosis who did not die by suicide, the researchers found that the genetic differences were more modest, with variation in the expression of 44 genes. When comparing individuals who died by violent suicide with individuals in the neurotypical group, the researchers found variation in the expression of eight genes.

Weinberger cautioned that the findings should not be taken too broadly. “We are getting a glimpse of one brain region at one moment frozen in time, right before an individual’s death.”

Several of the genes that were over-expressed in people who died by violent suicide relative to the other groups were involved in purine signaling. Purines are a class of neurotransmitters that regulate energy metabolism as well as some behaviors, notably aggressive behaviors.

“It is a big ask, but we do need to see data from other brain regions to form more solid conclusions,” said Alexis Edwards, Ph.D., an associate professor at the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics at Virginia Commonwealth University. Edwards added that an individual may have chosen a firearm for suicide simply because it was most readily available and/or made the decision hours, days, or even weeks before the actual act. It’s therefore possible that gene expression at death reflects factors other than the individual’s selection of a violent method.

Additionally, Edwards noted, experts remain divided on what to consider a violent suicide. For instance, poisonings may be considered nonviolent, yet they can be more prolonged and painful than firearm suicides, she said. Still, she said, this study is valuable in detailing the complexity and heterogeneity of suicidal behaviors. “Many people still see suicide solely as a feature of depression, and that is not the case.”

As part of the study, Weinberger and colleagues also analyzed genome data from another set of 888 DNA samples collected from people who were neurotypical or diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression, or bipolar disorder who died by various means. They found that people with schizophrenia or depression who died by violent suicide appeared to have less genetic risk for their diagnosed psychiatric disorder compared with people with these illnesses who died by nonviolent suicide or other means. These genetic discrepancies between people who died by violent suicide versus nonviolent suicide were not as pronounced in people with bipolar disorder, they noted.

Taken together, these findings support the idea that biological mechanisms underlying violent suicide may be distinct from those that increase suicide risk in people who have a psychiatric illness, Weinberger noted.

“[A]ddressing suicide by violent means as a separate condition may prove decisive to inform prevention,” Punzi and colleagues concluded in the paper. “Violent suicide [biomarkers] in brain specimens, if mimicked by peripheral biomarkers, may potentially differentiate a suicide candidate from a patient who is not shifting from considering death to actually pursuing it, offering novel and more precise targets for therapy in short-term risk for suicide.”

This study was supported by the Lieber Institute for Brain Development. ■