“I felt disappointed and was so angry at the psychiatrist. We waited three months for this appointment and got a half-hour where we shared basically nothing about our son’s life, except his ‘symptoms.’ He has no idea who we are or who our son is. We got a prescription, a huge bill, and an appointment for a ‘med-check’ two weeks later.”—Jennifer, parent of a 15-year-old with depression

It may seem unbecoming to begin this report on children’s mental health on a surgical note. But there are at least two good reasons that we are doing so. First, we ask you to consider the answer to that old chestnut “Why did some of us become psychiatrists?” Perhaps it was because surgery wasn’t invasive enough. Surgery simply did not go sufficiently deep for some of our sensibilities. Second, and to learn from our colleagues in surgery and not just use them as strawmen for a tired quip, let’s give them this: Surgeons don’t for a second forget that scalpels are instruments, base metals at that. If only we psychiatrists had a similar mindset when prescribing our own pills. Alas, we forget all too often that our potions are partly instruments, base salts at times.

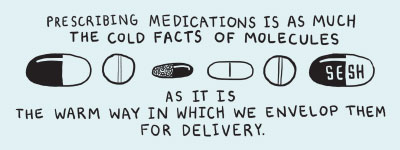

Our remedies are only as good as the way in which we dispense them—prescribing psychotropic medications to developing children is as much the cold facts of molecules as it is the warm way in which we envelop them for delivery. It is a reminder that no matter how accurate said delivery may be, it all goes to naught—molecules be damned—if there is no one on the receiving end; a psychotropic not taken is perfectly inert and useless. But our goal should not end at mere “compliance” (an unfortunate term that reeks of power dynamics and hierarchical paternalism); ingesting a pill and letting its molecules fulfill their job description are but the start of a therapeutic process.

Simple conceptualizations of depression as a low serotonin condition or of stimulants as dopamine enhancers are as incomplete today as they are misguided. A chemical’s docking, Apollo-like, onto a receptor’s site to right a neurotransmitter’s tenuous balance is as romantic a throwback as a 1960s moon shot. Advances in molecular psychiatry over recent decades have made it clear that psychotropics are more than simple “keys” to neurotransmitter “locks.” The contact of molecule and receptor may be a start, but it is the secondary, tertiary, and subsequent messengers where the action truly lies. It is these elusive messengers that get in deep, that get closer to the actual machinery of the cell, that get the job done.

In a similar way, we should not be mere prescribers, the holders of key rings on our proverbial tool belts. We are—or should be, or aspire to be, or reclaim being—pharmacotherapists. Our own job description gets started well before molecules reach their targets; we are cognizant that the moment of chemical bonding is but another start; we remain humble in our commitment, recognizing that to deliver on the full potential of our treatment, we, too, must become and remain the secondary, tertiary, and subsequent messenger systems. The prescription, the prescriber, and the prescribed are inherently intertwined; we ignore such bondings (chemical or otherwise) at our own therapeutic detriment.

Entering the Time-Frame Continuum

By focusing too narrowly on the dosing of milligrams or the number and class of psychotropic medications, we can easily come to forget that time is that other key aspect of our nosology. Time is perhaps our most valuable resource, and we would all do well to remember that “in psychiatry’s measure of time, more is more,” according to Arthur Caye, M.D., Ph.D., a contributor to our book. For example, in contemplating a patient who does not get better in the way or at the speed that we would hope for, we are comfortable—arguably too comfortable—increasing the milligrams or the number of psychotropics prescribed, and often both at the same time. We can capitulate in a similar fashion when facing some of the many outside influences that can intrude into the confines of our therapeutic relationship: unrealistic expectations for quick fixes or perverse incentives for “biological” treatments, as well as the pervasive influence of the pharmaceutical industry and the tentacular reach of its oversized advertising budget.

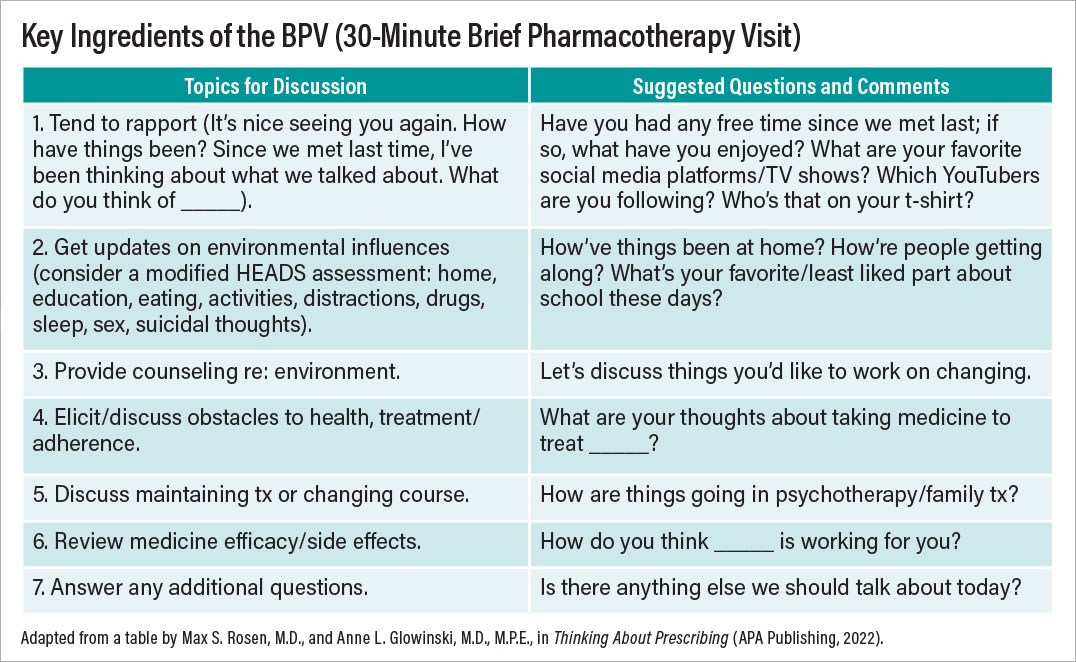

We urge you to resist being pushed to, yielding to, or (banish the thought) opting for the circumscribed role of “medication prescriber.” Our first and best defense against such a misguided interpretation of our role is to remember the centrality of time within and across clinical encounters, to reclaim the dosing of ourselves, of the number and frequency of our visits, of our presence and therapeutic engagement within them. If these words seem too idealistic and removed from the daily realities of a child psychiatrist, we want to move clinicians away from the term “med check” into the reality of the “brief pharmacotherapy visit (BPV)” to bridge the divide between what may be aspirational for some and what is possible for many. Milligrams dispensed are easy; time well spent is hard.

In pediatric psychopharmacology, establishing an appropriate frame is the yang to the yin of its time management. At the start of our book, Kyle Pruett, M.D., provides the pithy prescription for the task: “How you are with your patient is as important as what you do with your patient.” Three very different yet complementary chapters of our book help establish a robust frame through which to be with our patients. Our authors have adapted pharmacotherapy with children and adolescents from the “Y-model” first posited by Erik Plakun, M.D., and colleagues in the January 2009 Journal of Psychiatric Practice. The therapeutic alliance, as the stem of the Y, provides a common point of entry for any clinical approach. In its original description, that stem bifurcates into psychodynamic and behavioral arms. As appealing as such a neat tripartite model may sound, it only begins to tell the story when working with children and their families. The “stem” may instead be construed as more akin to a tree trunk, and the two arms as just two of the many branches in a complex canopy. Indeed, a multitude of synergistic approaches is what we are routinely called upon to muster as pharmacotherapists. Other chapters include those that apply psychodynamic principles to the context of pediatric psychopharmacology and that utilize cognitive-behavioral and motivational interviewing approaches.

There is an additional and more recent connotation to the “frame” under discussion—and that is the virtual frame through which more of our visits are taking place these days. What started as telepsychiatry in the 1990s, designed to reach remote and particularly underserved locations, has rapidly evolved and made major inroads into routine pediatric psychopharmacology. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic did in just a few months for the uptake of “virtual frames” what two decades of telepsychiatry educational efforts could not. Jeff Bostic, M.D., Ed.D., and David Kaye, M.D., have been pioneers and early settlers of these erstwhile barren virtual lands. They are also effective guides, enriching our vocabulary with terms such as tele-alliance, protection of the virtual space, telerapport, Freudian blips, screen empathy, and webside manner.

What once was “treatment not as usual” has by now become second nature. We should not envision a future devoid of physical visits, but rather embrace this new and complementary way of hitting the clinical target as an additional arrow in our therapeutic quiver. As we embrace e-prescribing over paper scripts (remember those?) and swoon over the powers of the pixel, we should not lose sight of the fact that many areas of the world do not have e-prescription capabilities and that families within even wealthy nations like ours do not have access to the internet or adequate bandwidth and may face other inequities and barriers to care, including those entrenched through structural racism.

At Least Three (Though It Can Still Take Two) to Tango

Pharmacotherapy with adults is largely a dyadic process between a patient and a prescribing clinician, an approach that at times works in the pediatric realm, particularly with adolescents and transition-age youth. However, the vast majority of time, prescribing psychotropic medications to children and adolescents involves other parties—at times several of them—each with competing priorities or agendas. For starters, given the enduring shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists, prescriptions often come from partners in a multidisciplinary team, including pediatricians and advanced practice registered nurses.

In another common approach, treatment may be complemented and synergized among prescribing and nonprescribing clinicians (“split treatment,” the commonly used term for this arrangement, is another unfortunate misnomer because it emphasizes the potential divide rather than the intended partnership). The potential for cooperation and for different vantage points on children, including their interactions with other children, is multiplied in schools or in congregate care settings such as inpatient units and residential facilities.

In navigating what can be such tricky shoals, we’d all do well to heed the aphoristic advice by Srinivasa Gokarakonda, M.D., M.P.H., and Peter Jensen, M.D., that “the messenger may be ‘wrong’ even if the message is ‘right.’ ” To be the best possible messengers and to maximize the odds of our thoughtfully selected treatments to be consumed, these authors emphasized the role of psychoeducation and cooperation as part of a partnership with common goals. With regard to working with children and adolescents, this duality most commonly involves parents or legal guardians. Establishing a caring and trusting relationship with them can be as critical to the success and longevity of our treatment as making the youngster feel at ease with us—and with our psychotropic stand-ins, which we ask them to faithfully ingest.

The richness of our work is in no small measure a reflection of the wide array of ethnoculturally diverse individuals and families we get to work with daily. And even as we respect their uniquely defining characteristics, we have found it helpful to approach clinical encounters—especially those involving the initial prescription of a psychotropic—through a framework that incorporates the perceived utility of the treatment on the one hand and the stance regarding treatment on the other.

Toward that end, the words we choose in pediatric pharmacotherapy are every bit as critical as the milligrams we dispense. As psychiatrists, we cherish words, though at times we overuse them. Prime examples of such verbal prolixity include the explanation of arcane and outdated mechanisms of action, an emphasis on encyclopedic side-effect lists, and a penchant for the legalese of informed consent. To make matters worse, these words have a way of morphing into reams of electronic boilerplate.

Surely there is a way to reclaim the healing power of pithier wordsmithing. And there is. First, go for the object. And the object in this instance is not the medication, but rather the child in front of you. Second, when addressing how treatments work, realize that “chemical imbalance” and the neurotransmitter hi-lo index may be more helpful in binding our own anxieties than those of our patients. Accept the fact that we don’t really know how our medicines work and step off the podium. When talking to kids, call the things “medicines,” not “medications” or (the horror!) “psychotropics.” A “pill” can be “candy,” and children do well to take neither one from a stranger. By contrast, a “medicine” is a known entity, and one that generally helps kids feel better.

When addressing side effects, beware of unleashing terms such as “sudden death” and “suicide risk”; these horses are hard to put back in their barns—not that you should elide them completely; follow instead your own advice to “start low and go slow.” Start, in fact, at the lowest, a truism that often goes unsaid: The most common side effect is no side effect. Build up from there: There are relatively common side effects that tend to be minor and well tolerated, and there are more infrequent and serious ones. Address the ones that are more likely to be pertinent, and remember that some things can’t be unheard. After a few minutes, only the most salient words are likely to stick. You don’t have to build Rome in a day—or, by frightening your audience away, demolish it in a day either. Obtain informed consent, but stop from making patients and their families feel part of an informed coercion process. And finally, did we mention going for the object? It is right there, staring you in the face.

Placebo, Nocebo, No Dice

The placebo effect gets a bad rap, what with all of its muddying of the clinical trials we base so much of our evidence base on. But the placebo effect deserves a closer look as more than methodological noise. The nonpharmacological powers vested in a medication, and the positive meaning and healing expectations attributed to it, can be powerful allies in leading to positive change. By contrast, placebo’s younger cousin, the nocebo effect, can be a force to reckon with because it can taint with its negative messaging, dashed hopes, and harmful attributions. When expectations are not only the patient’s but those of parents or guardians, of schoolteachers or coaches, as well as of social media–frenzied influencers, we need to pause to consider the interlocking effects of what David Grelotti, M.D., and Professor Ted Kaptchuk initially conceptualized for adults, and Efrat Czerniak, M.D., and colleagues termed “placebo by proxy” and “nocebo by proxy” effects for children and adolescents.

We may think of our consulting rooms as a confidential sanctum of privacy, but conversations about treatment rarely end at our door; they are more likely to only get started there, and we risk enlarging our blind spots if we sidestep this chorus of informative or inflammatory influences.

A self-defeating adolescent experiencing depression may resist a medication she considers herself unworthy of taking or that may threaten to alter distorted views deemed by then integral to her personality. Gentle yet goal-directed motivational interviewing may permit us to close the gap and “get to yes.” A parent or guardian may resist allowing a child to take a psychotropic out of an understandable abundance of caution, but there are times when untoward hesitation or repeated instances of abandoned treatment may require the involvement of child protective services. No one can force a child to take a medication, and the instance of involuntary administration (as in the case of an intramuscular injection) should remain a (very) last resort measure within an emergency department or inpatient setting. Long-acting depot antipsychotics don’t have a safety record in minors to warrant their regular use. In short, protective services, the courts, and injectable medications do have a role in contemporary psychiatry, but they are rarely invoked or useful beyond an acute emergency situation in the case of pediatric pharmacotherapy.

For many of these all-too-common scenarios, there are concrete suggestions we have found helpful in our own practice. Our oversharing of details—in the spirit of being transparent and comprehensive—can corner us into a resigned stance. We do not advocate for the outright omission of side-effect discussions, but we do make a case for being less meticulous and defensive. Take, for example, suicide risk in the context of starting an antidepressant. Time and again we hear necessary and well-meaning conversations about the relative risk of emergent suicidal ideation among children taking antidepressants compared with those who are unexposed. So far, so good. But what we all too rarely hear is the more relevant comparison—higher rates of death by suicide among the untreated. Our cathartic confessionals scare away more often than they meaningfully engage patients and their families: We should resist snatching defeat (in the form of losing a patient to follow up or, tragically, to suicide) out of the jaws of victory (in the form of starting a potentially lifesaving medication embedded within a therapeutic relationship).

Our task is in no small measure one of shared meaning-making. Magdalena Romanowicz, M.D., and her colleagues were direct and aphoristic in their advice when they reminded us how the parent and patient most often seek consultation to receive help with their problems and not to receive a DSM diagnosis. Our task is to assist them in creating meaning and making sense of symptoms. In an important article in the August 2019 issue of Psychodynamic Psychiatry, David Mintz, M.D., expanded this notion, alerting us to attend to the meaning of medication, particularly given that “[w]hile all people who take medications may attach pathogenic meanings to them, children and adolescents may be particularly vulnerable, because such effects can be amplified when incorporated into unfolding developmental processes.” Moreover, “when harm occurs at the level of meaning, the problem will be most usefully addressed at the level of meaning. Far too often, however, medicated children receive little or no psychological treatment.”

A Bitter Pill to Swallow: Stigma

Side effects (for example) may be the manifest excuse to turn down medication treatment, when closer listening may reveal that the stigma of mental illness is the more relevant latent message. To take (or to give) a medication may be seen as tacit endorsement of an unwelcome diagnosis, of “otherness,” of frailty or fallibility we would rather ignore. As if the stigma of mental illness was not bad enough, the stigma on psychotropics can increase messages of exclusion and isolation, of being “broken” and in need of “repair.”

There is much that we can do in our daily fight against the stigma of mental illnesses and the medications on which we often rely to treat them. Psychoeducation is certainly prominent on the to-do list. But there is something else worth considering. It will sound radical, provocative, or boundary breaking to some, and we respect those views. But for some others, being a bit radical, a tad provocative, a pinch boundary breaking, and a whole lot legitimate and human can be game-changing.

Specifically, we have used as a tool for good the careful, selective sharing of our own diagnoses, treatments, medicines, family struggles, and recoveries. Whenever we have done this with the patient’s well-being in mind, when the sharing has been genuine and caring, when we have met with patients and their families in our full shared vulnerability, at those moments, we have been pediatric pharmacotherapists, physicians, and humans at our very best.

We are not alone in this endeavor, and we embrace the sage and insightful words of our courageous and pathbreaking colleague, Stephen Hinshaw, Ph.D., in his 2017 book, Another Kind of Madness: A Journey Through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness. He wrote that “fostering humanization may be the single most important weapon in the fight against stigma for ... [m]ental disorders don’t afflict them—a deviant group of flawed, irrational individuals—but us: our parents, sons and daughters, colleagues and associates, even ourselves.” Thus, though we have nothing to disclose, we do have much to share. In short, we invite you, dear fellow prescriber, to prescribe thyself. ■

Author Disclosures

Andrés Martin, M.D., M.P.H., and Shashank V. Joshi, M.D., receive revenue from APA Publishing and have no other financial conflicts to disclose.