Old photos and other memorabilia have a special importance for many of us. Saving them helps us keep our family members interconnected. In my case, I have long held tightly to my father’s gift of his 1936 edition of the two-volume Webster’s Universal Dictionary and the undated edition of Robert Young’s Analytical Concordance to the Bible. These objects are not yet ready for distribution! Processing these notions of archiving, I immediately remembered a friend who recently donated a collection of stuffed animals to someone with a young child. There were two puppets in the collection, I was told, which the donor used to communicate with a younger sister. She was hoping the beneficiaries of the gift would reproduce this wonderful experience within their own family.

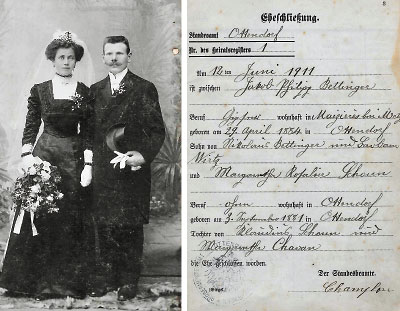

A woman, who migrated years ago from France to the United States, carefully kept pictures and documents that reflect details of her lifelong history. The picture and marriage certificate on the facing page come from the family archive and focus on the 1911 wedding of her maternal grandparents. The photo was taken in the department of Moselle, a region in northeast France. This geographic area had been under German occupation since the 1870s, which accounts for the German language used in the official document. The region would revert to France at the end of the first World War and experience similar upheaval between 1939 and 1945. The archive’s owner points out the details of the figures in the picture: their stylized clothing and coiffures, the top hat and white gloves, and their personal bearing. The photograph is an important reference point, as she got to know these relatives only from about the late 1950s.

The Oakland Museum of California recently hosted an exhibition about Angela Yvonne Davis, the feminist and avowed Communist so beloved by the political left. She is a prolific scholar concerned with matters of class, gender, race, and prison affairs. It turned out that some of the material displayed in the museum program came from the collection of the community archivist Lisbet Tellefsen. On show was, for example, a stunning group of posters pulled together over the years that featured the visage of Angela Davis. In conjunction with the exposition, Tellefsen and two other archivists, Damien McDuffie and Odette Pollar, staged a didactic presentation about community archiving. The program title, “Preserving Black Memory: A Conversation With Oakland Culture Keepers,” captured their interest in safeguarding memories about the Black community and reinforcing citizens’ identities and personal pride.

These unique audiovisual lectures and conversations held the audience’s interest and provoked considerable interchange during the question-and-answer period. The speakers described their collecting as a strategy for keeping Black history alive. However, I also saw their efforts as having broad application to many cultures. Most people I know depend on safeguarding objects, information, principles, and rituals for future use. The presenters pointed to their involvement in childhood practices such as accumulating matchbooks and photos. They also were exposed to relatives who had developed habits of putting aside groups of objects.

Tellefsen declared a penchant for materials with a political history. Hence, her interest in Angela Davis posters and other information about the Black Panther Party. Pollar demonstrated her long interest in a community club called “The Rainbow Sign.” That organization facilitated gatherings of Blacks for social, political, and educational purposes. They held dance classes and poetry readings, for example, as Blacks had little access to this kind of community institution. McDuffie described his compulsion to take photographs of life in the Black community of Oakland, Calif. As the three lecturers talked, it became clearer how each had envisioned a way to put a personal imprint on some aspect of the local Black culture. They discussed several definitions of community archiving: keeping family history alive, preserving memories of a single institution, collecting materials that will provide information for future users, and engaging in activity that flows from visualizing oneself as part of history. The discussants encouraged members of the audience to engage in archival collecting, even while making clear that preserving and passing on collections to others remain complicated tasks.

Returning to the French family archive, the picture and document provide some insight into the hardships that flowed from the cultural, linguistic, and political changes forced by several major wars. This archivist recalled having to speak German with some relatives who spoke no French. She also noted that individuals from this northeast area of France, who had been raised in this Franco-Germanic context, were stigmatized because they manipulated French with difficulty and spoke it with a German accent. They seemed out of step with the aesthetics of French life. In private, they talked of feeling like outsiders.

The archive’s owner takes pride in a family line that stretches historically over a hundred years or so. She understands the subtleties of caste and culture and bristles at the oversimplification of discrimination and othering. She argues passionately that information about one’s origins helps us all withstand the arrogant claims of those who advocate maintenance of the caste ladder because they like being on its dominant rungs. The archived past gives clarity to one’s present vision of things. ■