Casey is a 57-year-old woman with a lovely smile and deep sadness in her eyes. She appears composed when she enters the therapist’s office but is quick to get teary while explaining what brought her in. She does not understand why her grief does not lessen. It has been more than four years since her son Daniel died of an accidental overdose, but she can still barely function. She manages to go to work, but otherwise, she does not want to see anyone or leave her house. She tells the therapist that, honestly, she doesn’t believe anyone can help her, but she doesn’t know what else to do and is willing to give this therapy a try.

Casey avoids all social occasions, including seeing her friends, because it takes too much energy to put on a “happy face.” She also avoids places and situations that remind her of Daniel because it feels like too much to bear. She is disappointed in herself for not being able to cope with this loss after so much time and feels she should be improving by now. Sometimes she is angry at the police for not doing more to catch drug dealers and at society at large for not doing more to stop the opioid epidemic.

Casey often thinks she should have died instead of Daniel and wishes that one day she would just not wake up so this torture would end. Her strong religious beliefs are all that keep her from trying to take her own life. She does not recognize herself anymore. Who is this weak person?

The publication of diagnostic criteria and clinical diagnostic guidelines for prolonged grief disorder (PGD) in DSM-5-TR and in the ICD-11 could not be more timely or important. We find ourselves emerging from a global pandemic that has occasioned immense dislocation and disconnection: social, economic, political, medical, psychological, and spiritual. Our world has been turned upside down.

In its wake, COVID-19 has wrought another pandemic of suffering: bereavement, acute grief, prolonged grief, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use, and suicide. Many of us were touched personally by the pandemic through the loss of close relatives and friends. In addition, the ongoing epidemic of gun-related violence, particularly against children, older adults, and people of color, as well as the escalating rates of death due to fentanyl exposure, greatly magnifies the occasions for loss and prolonged grief.

It is in this context that the editors of Grief and Prolonged Grief Disorder seek to offer science-based guidance to help psychiatrists, other physicians, other mental health clinicians, and the lay public understand typical (“normal”) grief—that is, the process of adaptation to and acceptance of the finality of death—and to recognize when that process has been derailed.

Under the latter circumstances, grief becomes prolonged, with an intense preoccupation with the loss as if it had occurred just yesterday. Grief and longing remain, with no relief in sight; rather, the grieving person continues to long for the lost loved one to the exclusion of healing and getting on with life’s journey. Absent a focused intervention, this state may last for months, years, or even decades. The failure to envision and restore a life of meaning without the loved one, together with profound suffering and impairment in major role functioning, constitutes the essence of PGD as defined by diagnostic criteria in DSM-5-TR.

As is now recognized by both APA and the World Health Organization, PGD does not represent in any way the “medicalization” of grief, nor is it in any way the same as major depression. On the contrary, PGD has been adjudicated by the DSM-5-TR experts to fulfill the DSM-5 criteria for a distinct mental disorder. This declaration follows decades of considered research that amassed a large body of evidence supporting the need to recognize this distinctive condition. It can be diagnosed reliably and distinguished clearly from typical grief and co-occurring or preexisting disorders (such as major depression or PTSD). Most important of all, it can be successfully treated, not with interventions for major depression or PTSD, but with a specific psychotherapy—prolonged grief disorder therapy (PGDT). PGDT is theoretically grounded in models of attachment and contemporary understanding of emotional dysregulation. In addition, PGDT addresses maladaptive, avoidant coping, and counterfactual thinking.

The failure to recognize PGD puts the bereaved at risk not for stigma (as “medicalization” critics contend), but rather for protracted suffering, poor physical health, social isolation, loneliness, cognitive impairment, shortened life expectancy, and suicide. With advances in grief science, clinicians are now better able to assess accurately those living with prolonged grief, perform a differential diagnosis, and advise specific treatment that has established efficacy and safety. These tools are particularly important amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the epidemic of assault-weapons violence and fentanyl exposure.

Diagnosing Prolonged Grief Disorder

The DSM-5-TR criteria for PGD require that distressing symptoms of grief continue for at least 12 months following the loss of a close attachment and that the grief response be characterized by intense longing/yearning for the deceased person and/or preoccupation with thoughts and memories of the lost person nearly every day for at least the past month.

These symptoms result in clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, and/or other important areas of functioning. As a result of the death, at least three of the following eight symptoms must be experienced to a clinically significant degree:

1.

Feeling as though a part of oneself has died.

2.

A marked sense of disbelief about the death.

3.

Avoidance of reminders that the person has died (often coupled with intense searching for things reminiscent of the deceased person and/or evidence that the person is still alive, such as mistaking others for the person who died).

4.

Intense emotional pain (anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death.

5.

Difficulty with reintegration into life after the death.

6.

Emotional numbness, particularly with respect to an emotional connection to others.

7.

Feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death.

8.

Intense loneliness as a result of the death.

The duration and severity of the bereavement reaction clearly exceed social, cultural, and/or religious norms for the individual’s culture and context. Additionally, the symptoms cannot be better explained by major depressive disorder or PTSD or attributed to the physiological effects of a substance—medication or alcohol—or to another medical condition.

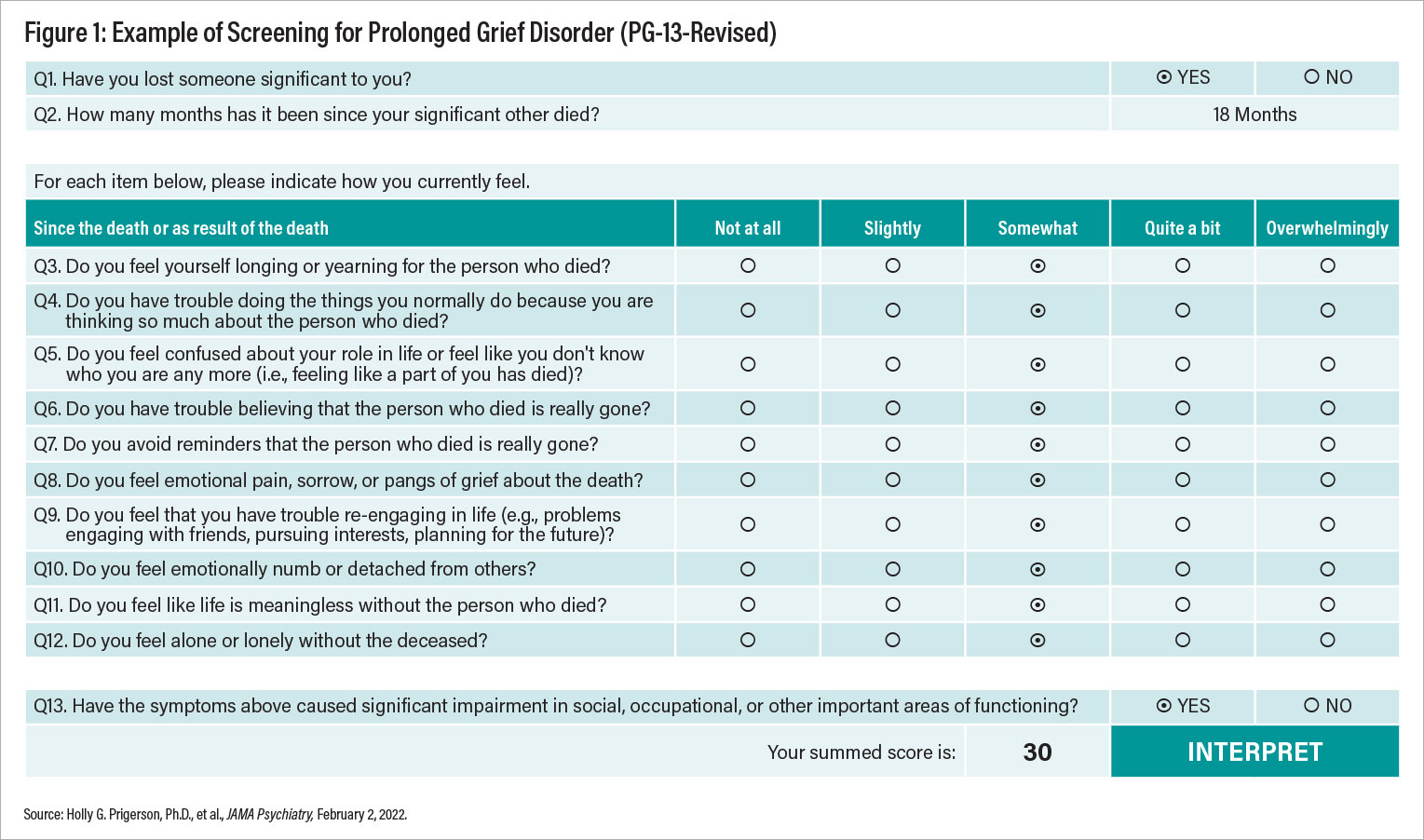

The performance characteristics of the PGD diagnostic criteria and the PG-13-Revised (PG-13-R) scale have been extensively researched and published by one of the authors of this report (Holly G. Prigerson, Ph.D.) and her colleagues in the January 12, 2021, issue of

World Psychiatry. The PG-13-R is a useful self-report measure of the syndrome that can be used to screen for the diagnosis and estimate its severity; it maps onto

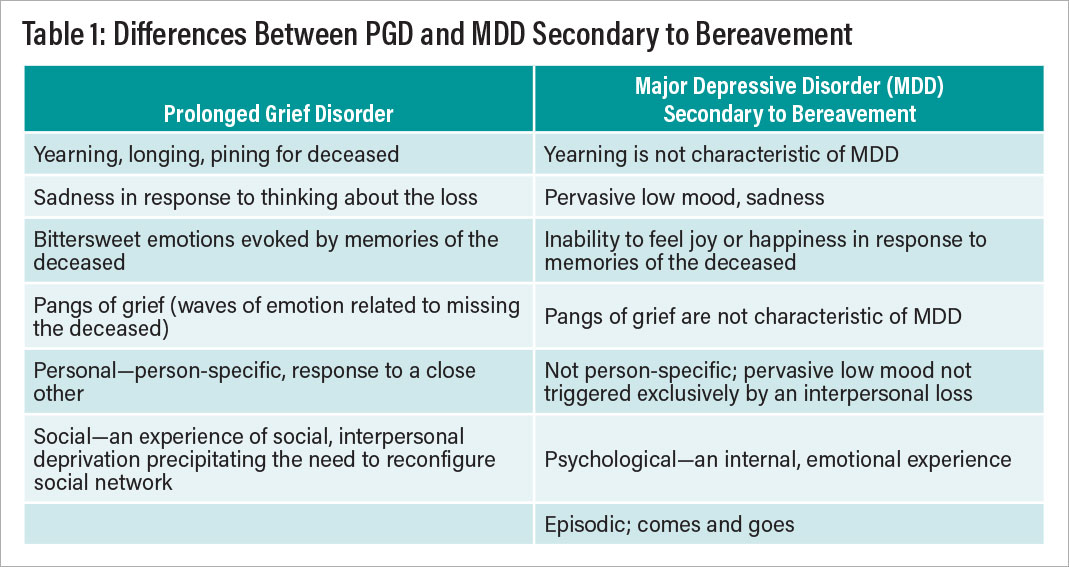

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria, and a summary score of 30 or greater is consistent with a diagnosis of PGD and indicates further evaluation and treatment (see Figure 1). Table 1 indicates the differences between prolonged grief disorder and major depression secondary to bereavement. Table 2 lists common misunderstandings of the PGD construct.

PGD Patients Respond to Treatment

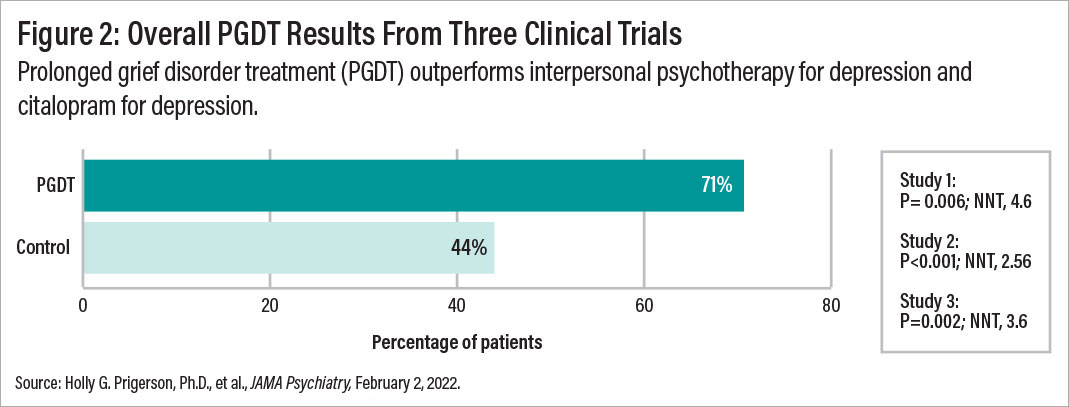

PGD can be successfully treated, as shown in three separate NIMH-sponsored randomized, clinical trials led by M. Katherine Shear, M.D., comparing a 16-session PGD-targeted therapy versus treatment efficacious for major depression. As shown in Figure 2, among a total of 641 participants,

the overall PGDT response rate, as indicated by a rating of 2 or 1 (that is, “much improved” or “very much improved”) on the Clinical Global Impression Scale was 71% versus 44% for depression treatment using interpersonal psychotherapy or citalopram. Participants were aged 20 to 93 years, bereaved of a range of losses by natural or violent causes. Most had already received grief counseling and/or mental health treatment. In the

largest of the three randomized clinical trials, HEAL (“Healing Emotions After Loss”), published in July 2016 in

JAMA Psychiatry, no difference was found between citalopram and placebo in the resolution of PGD symptoms, in contrast with the markedly better response rates for PGDT than for no-PGDT. Importantly, the combination of citalopram and PGDT resulted in better resolution of depressive symptoms compared with PGDT and placebo, though combined treatment led to no better resolution of PGD symptoms than PGDT alone. Other similar therapy approaches in single trials, most using cognitive-behavioral therapy methods, have also been tested and have demonstrated efficacy; these are presented and reviewed in our book.

PGDT helps promote adaptation to loss and restoration of life through seven healing milestones:

3.

Seeing a promising future.

4.

Strengthening relationships.

5.

Narrating a story of the death.

7.

Connecting with memories.

The central premise of PGDT is that loss triggers acute grief and a natural adaptive process by which grief is transformed and integrated. A further premise is that persistence and predominance of early grief coping responses (for example, protest, self-blame, anger, counterfactual thinking, and avoidance) derail this process. The objective of PGDT is to facilitate adaptation and to address these derailing symptoms.

Adapting to loss involves learning to (1) accept the new reality, including the finality of the loss, a change in the relationship to the deceased, other changes in the world, and the permanence of grief; and (2) restore the capacity for well-being, including a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The seven themes, or healing milestones, around which PGDT is organized are introduced sequentially with core procedures for each:

1.

Understanding and accepting grief.

2.

Managing grief emotions—both painful and positive (grief monitoring and psychoeducation).

3.

Seeing a promising future (aspirational goals).

4.

Strengthening relationships (inviting a significant other to join a session).

5.

Narrating the story of the death (imaginal revisiting).

6.

Living with reminders (situational revisiting).

7.

Connecting with memories (imaginal conversation).

The Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Research on an End-of-Life Care has posted a number of clinician resources on PGD, including a tutorial on how to make a differential diagnosis. The PGD diagnostic criteria and the PG-13-R screener provide useful tools for bridging science and care. In addition, a PGD therapy tutorial, developed at the

Center for Prolonged Grief at the Columbia School of Social Work.

Preparing for Grief

We know that loss is inevitable in life, that “grief is an innate part of what it means to live a full and rich life as a human.” So wrote A.C. Shilton in “

There Is No Vaccine for Grief” in the March 2, 2021,

New York Times. In other words, grief follows from love and close attachment to others and thus is inextricably bound with a life filled with meaning, joy, connection, and sorrow.

Shilton’s question—Can one fortify oneself for grief?—is foundational for all of us, because grief is universal. Can one nourish resilience to navigate the journey of grief and protect oneself from grief becoming prolonged and disabling? It seems particularly appropriate and timely to address this issue head-on.

Shilton suggested that it may be possible to prepare oneself for grief and advocates five broad strategies for doing so:

1.

Practice experiencing your emotions.

2.

Shower the people you love with love.

4.

Recognize your coping style.

In the foreword to Grief and Prolonged Grief Disorder, we contextualized the clinical management of grief and its complications within a broader framework, including the COVID-19 pandemic. To elaborate: We can inoculate ourselves against the COVID-19 virus and its variants or, more precisely, against its complications: severe illness, long-haul disability, and death. We know that behavioral measures, based in public health, are central to reducing viral spread and replication and, thereby, the genesis of even more transmissible and potentially lethal variants, such as Delta and Omicron.

By analogy, we ask whether there is a “vaccine” that could inoculate us against prolonged suffering, disability, and suicide—born of the inability of grievers and their supporting friends and family to recognize and set aside early defensive processes that entail turning away from the reality of the loss. Put differently, and more affirmatively, is there a vaccine that could nourish resilience, so that one’s “bank account” of resilience is available in the face of losing a loved one? Can such inoculation enable a healthier, more adaptive response and prevent complications such as PGD?

This question is about the science of preventing PGD. But the answer can be informed by strategies that facilitate natural adaptive processes oriented toward accepting reality and restoring the capacity for well-being in the days, weeks, and months after the loss of a loved one.

Drawing on another metaphor: A wound heals naturally in the absence of complications, such as infection or diabetes, that interfere with the body’s restorative processes. By analogy, an important loss brings myriad disruptive changes that evoke natural adaptive healing responses. As adaptation progresses, the experience of a loss changes, the new reality becomes integrated into everyday life, and grief follows suit. But the process of adapting can be derailed if a griever’s initial defensive coping responses persist and are overly influential in mental functioning—and perhaps for other reasons that continue to be investigated. When adaptation is stalled, the experience of the loss remains fresh and grievers get stuck in the throes of acute grief, which only reinforces the use of defensive coping. The architecture of risk and protection against PGD, while still an evolving science, is becoming clearer.

We are fortunate that there are short-term, evidence-based methods to treat patients with PGD. Also, we look forward to a time when we will know specific strategies for building resilience, helping those with acute grief to learn how to navigate the journey in an adaptive way and thereby protect against the development of PGD.

Conclusion

The key clinical and scientific point that we wish to emphasize is the need to build and test hypotheses addressing the prevention of PGD and to determine what works for whom, how, and when. As our field has learned in depression prevention and treatment research, this type of investigation is vital to bridging intervention science with clinical care. At the same time, progress in understanding the neurobiological substrates of PGD is accelerating through the availability of tools for functional brain imaging and measuring peripheral molecules, such as endocannabinoids, which moderate stress responses. Brain network biomarkers of emotion dysregulation and dysfunctional reward processing may serve as predictors of worsening grief trajectories, including the development of PGD and accompanying psychiatric complications such as major depression and PTSD.

Moreover, given the availability of a highly effective, specific, and safe treatment—PGDT—we can now ask and seek answers to questions about the moderators and mediators of treatment effectiveness. We can use PGDT as a probe to better understand the mechanisms by which depression, PTSD, and loneliness pose risk for complicating and prolonging the course of grief.

We hope that Grief and Prolonged Grief Disorder will further stimulate such science and its translation into real-world care. Most of us—if not all of us—will need the fruits of such science sooner or later, as well as the loving care we trust and hope it may beget. ■