The updated International Association for the Study of Pain definition recognizes pain within a biopsychosocial framework (

3) and considers biological, psychological, and social factors contributing to the experience. A recognizable cause of pain cannot always be found, rather, underlying emotional and social factors are at play generating or triggering the pain and unexplained somatic symptoms (

2,

4). Triggers include anxiety, depression, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Emerging studies consider the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include abuse and neglect during childhood years, as notable generators for chronic pain in later life (

5).

Plentiful options exist for the management of chronic pain, but effective and safe strategies are lacking. Opioids are an option, but side effects and potential for substance use disorder are major concerns (

6). Furthermore, treating physical pain alone is rarely effective due to underlying emotional and social pain generators (

7). Therefore, mind‐body therapies (MBTs) such as meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness are sometimes employed (

8). While the literature is replete with studies testing MBTs, only small reductions in pain are reported (

8,

9,

10,

11). A 2020 systematic review from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) assessed the impact of MBTs for chronic pain conditions and suggested more studies in this area (

12).

Holographic Memory Resolution® (HMR), a mind‐based therapy without somatic movement was developed by Brent Baum in the early 1990s. He and several others have been using HMR® to treat individuals with a variety of complaints including depression, anxiety, pain, and PTSD. HMR® incorporates elements of energy psychology, guided imagery, and clean‐language interviewing (patient‐centered without practitioner input) into a single approach with the aim of changing the emotional component of a negative memory to resolve psychological distress (

13). Despite being used for decades, only unpublished data exist; no published studies were found that report the outcomes of HMR®.

Due to the dearth of research in this area, the primary aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of administering HMR® to individuals experiencing chronic pain and its related biopsychosocial symptoms. Our secondary aim was to measure preliminary efficacy of HMR® on pain and its accompanying symptoms. We hypothesized that HMR® would be feasible and improve anxiety, depression, PTSD symptoms, and vitality in participants with chronic pain. Participant perceptions and self‐determination theory mediators and outcomes were also explored but will be reported elsewhere.

DISCUSSION

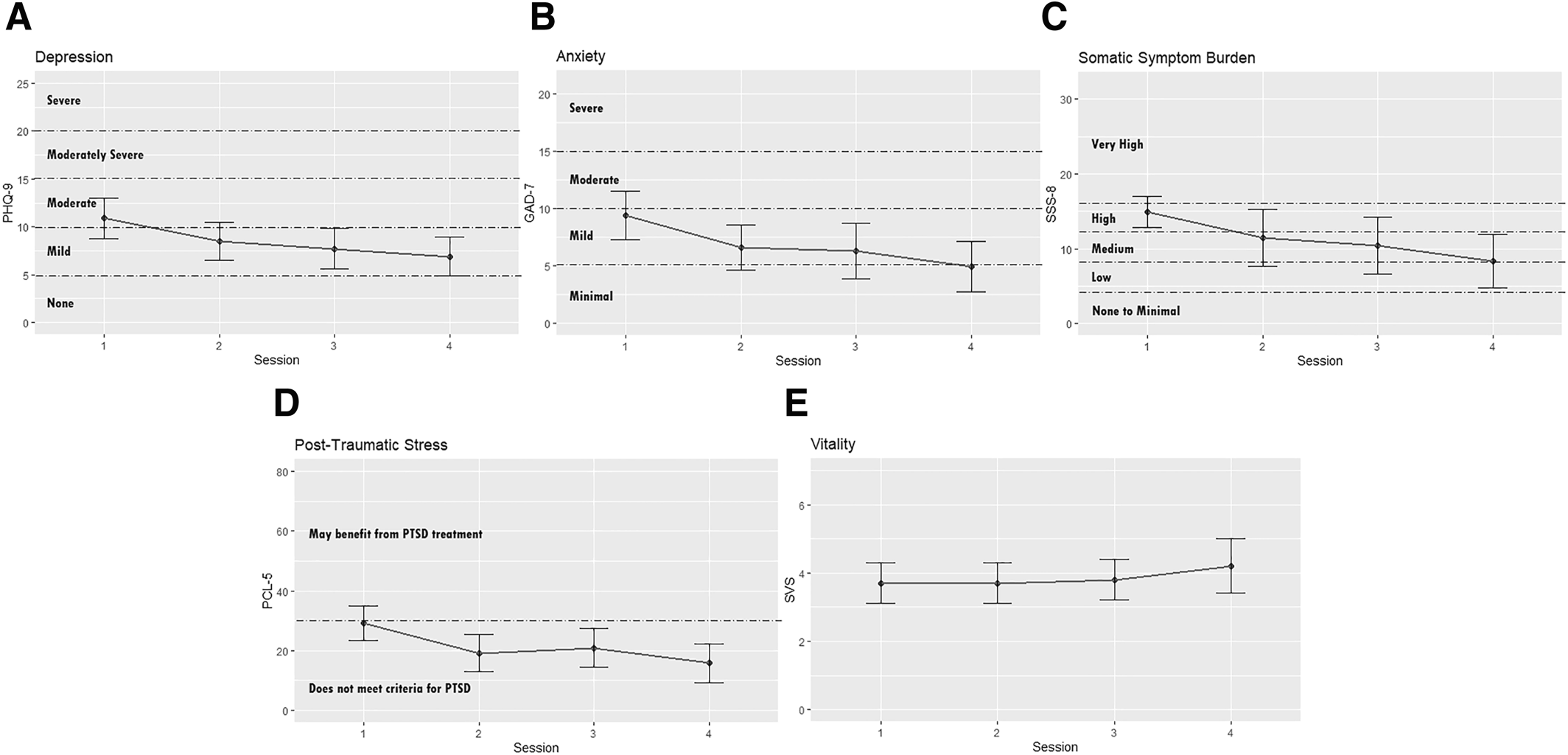

This study is the first known to report outcomes of the use of HMR® as a feasible intervention and suggests significant improvements in anxiety, somatic symptom burden, and PTSD associated with chronic pain and its associated symptoms. These are notable outcomes in a population that has often sought multiple providers and treatments to manage their symptoms.

Demographically, women were more likely to participate in our study than men, consistent with other MBT studies (

30). Regarding ACEs, almost 100% had at least one ACE; 31 participants (over 50%) experienced 4 or more which places them at high risk to develop toxic stress response and associated chronic illness (

15).

When comparing our study to other MBTs for chronic pain in the literature, we have chosen to review only systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of mind‐based therapies without somatic movement due to the plethora of studies that exist. A Cochrane review of 75 studies (

n = 9401 participants) examined CBT, behavioral therapy (BT), and acceptance commitment therapy (ACT) for chronic pain, and found a small benefit for CBT, but no evidence was demonstrated for BT or ACT (

11). An AHRQ review of 233 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with similar population parameters to our current study (low back pain [LBP] and fibromyalgia [FM]) revealed CBT was associated with small improvements in LBP short‐term (−0.75 per a 0–10 scale, 1 to <6 months post‐MBT), intermediate‐term (−0.71, 6–12 months post‐MBT), and long‐term (−0.55, >12 months post‐MBT) whereas mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR) demonstrated small improvements intermediate‐term. For FM, CBT was associated with a small improvement in pain compared to a control arm short‐term (−0.62) but not intermediate‐term. No clear short‐term reductions of function and pain were found for MBSR short‐term, but small improvements were noted immediate‐term. Our study suggests consistency with these findings. Pain, which was part of somatic symptoms, was aggregately reduced from a very high to medium range by the end of the study period.

Regarding emotional symptoms, 11 systematic reviews with 20 meta‐analyses reported a small to moderate benefit for mind‐based interventions (meditation and mindfulness) on depression in patients with chronic pain (

9). The sample was similar to ours in that the majority of participants were middle‐aged women. Interventions had a small to moderate effect on depression in chronic pain conditions. Depression and symptoms of anxiety, a common component of depression, both significantly decreased in our study.

PTSD, which often co‐occurs with chronic pain, was found in a sizable proportion of participants in our study. MBTs are widely recommended in the treatment of PTSD and chronic pain (

31). One study using Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a commonly used MBT for PTSD, noted 50% of patients had improved anxiety and PTSD symptoms compared to 0% of patients in the control group (

32). The significant improvement in PTSD symptoms reported in our study warrants a RCT to confirm results.

While we have tried to compare our study to other MBTs without somatic movement, it is important to note that HMR® is not the same type of intervention, rather it embraces holonomic philosophy. “Holonomic” is derived from Karl Pribram's work in which memory in the physical body is not distributed equally as would occur in a holographic system but is evidenced as more site‐specific in the human body (

33). This enables the HMR® practitioner to target a specific memory at a specific site, which is unlike any other therapy.

The practitioner employs a clean‐language approach, empowering the participant to use their personal internal language to gently access and transmit proof of safety to the specific moment and site of trauma encoding. Since every moment of trauma encoding involves a unique set of personal frequencies captured when consciousness is bound or paused, the participant alone can determine the missing frequencies or colors that restore safety. Early childhood developmental safety may be established via sight, sound, or olfaction even before language is established. Focus on the holonomic fragment of a memory provides access to the whole memory. The participant is offered resources to provide expedient assistance in resolving psychological and physiological distress in the effort to reduce state‐bound symptoms without re‐live or abreaction.

EMDR has proven effective in reducing the impact of adult memory but is less effective with childhood memory. Since HMR® creates sufficient safety to enable the participant to maintain dual states of consciousness, the adult's vocabulary can be used to access, articulate, and address the pain of the wounded parts. HMR® is more participant‐centered and body‐centered than thought field therapy/emotional freedom technique or energy psychology approaches in that it does not depend on the therapist's guidance or utilization of pre‐determined neural pathways or meridians but allows the participant's own internal mapping process to dictate the proper site of access and resolution. Since the conscious, rational, moral mind is recognized as 5% of consciousness, HMR® targets the 95% subconscious mind where trauma imprints and is stored.

While CBT has proven helpful in addressing the cognitive and behavioral impact of trauma, HMR® focuses on effective methods to discharge the affect or emotion which binds one to trauma or abuse and, therefore, was termed an “emotional reframing” technique, versus a cognitive approach. Individuals who perseverate with past traumatic events are often initially emotionally overwhelmed, which then produces subsequent cognitive and behavioral effects. While CBT helps a participant to become aware of inaccurate or negative thinking, HMR® seeks to address the affective trauma which precipitates, underlies, and results in adverse thought forms and behavioral coping mechanisms. That which attaches us to memory and the adverse effect of trauma is the emotional charge, which binds us to adverse thoughts. HMR® was designed to address and to help resolve the emotional attachments created through trauma and overwhelm. By remaining participant‐centered, body‐centered, and utilizing a strict clean‐language approach with no authoritative hypnotic induction employed, the possibility of false memory introjection for the participant is avoided.

Limitations

Several limitations are acknowledged in this study. First, this was a feasibility study without randomization, or a comparison group. Second, the timing of sessions for the intervention was variable to accommodate patient schedules. Regardless of the session schedule, an overall improvement in symptoms was observed. Third, specific pain scores were not consistently captured. HMR® practitioners indicated participants experienced pain that was difficult to quantify, and as therapy ensued and memories surfaced, pain would emerge in other parts of the body not previously reported. Finally, this sample lacked racial and ethnic diversity; therefore, these findings may not generalize to other populations.