Individuals released from prison have an increased risk of overdose death compared to their demographic nonincarcerated counterparts (

1,

2,

3). The heightened risk of drug overdose death, in contrast to the general population (

4,

5), disproportionately affect females (

6) and whites (

2,

6,

7,

8) in prison and is further elevated within the few weeks following release (

1,

9). These overdose deaths in the post‐release period predominantly involve opioids (

10) and remain the leading cause of death for individuals that return to communities from prison (

1). Factors that contribute to overdose deaths after release from prison, include various demographics, such as, gender and race (

6,

7,

11), as well as histories of mental health and substance use (

6,

8), socioeconomic status (

12), and incarceration related factors (

2,

6,

7,

8,

13).

Admission to prison, in and of itself, can elevate the risk of an opioid overdose death. Individuals undergo abrupt changes in drug behavior upon correctional admission (

14), which include, reductions in frequency of use (

15), purity of substances consumed (

15), as well as increases in solitary substance use (

16). Disruptions in social networks—a critical tool for individuals that seek recovery from substance use—can also occur on an account of imprisonment, such as, rises in interpersonal relationships with companions that experienced overdoses (

17,

18), and halted communications with established and trusted dealers, which coax individuals to purchase from unfamiliar sources upon release (

11,

19). Other exposures of imprisonment, such as, restrictive housing (

20) and higher security prisons and criminal justice supervision (

20,

21), further increase the level of vulnerability an individual has to drug overdose mortality after release. Though, interruptions in healthcare, such as, reductions in substance use treatment and harm reduction services (

12,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27), often take precedence in post‐release discussions on overdose deaths bearing their profound effects on substance use outcomes.

Access to Medicaid—the principal payer of post‐release health care services (

28)—remains critical for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) for continued health care upon release. State expansions in Medicaid has been associated with increased enrollment (

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34) and streamlined access to various healthcare services upon release, such as treatment services for OUD (

35,

36,

37), services for mental health (

31,

32), and other healthcare services (

30,

32,

38), thus supporting efforts to mitigate overdose death (

22,

39). Moreover, these state expansions in Medicaid, as well as federal expansions, reduce financial barriers to access treatment services and may even assist with recidivism (

32,

40).

Recognizing these benefits, Pennsylvania has made Medicaid more accessible for individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Prior to 2017, Medicaid coverage terminated upon entry into the criminal justice system and individuals had to reapply for Medicaid upon release. This often caused a lapse in insurance coverage at a particularly vulnerable time for the individual. In May of 2017, Act 76 was amended to authorize the suspension, rather than termination, of Medicaid benefits for imprisoned individuals, which streamlined the process of restoring access to Medicaid coverage after release. Supporting Information

S1: Supplement A provides a chronological representation of various Medicaid policy changes pertinent to individuals with criminal justice involvement in Pennsylvania between 2011 and 2020.

Although previous studies have established that state Medicaid expansions have led to increased Medicaid enrollment and streamlined access to post‐release healthcare services, the effects of Medicaid expansions, such as coverage suspension during imprisonment, on opioid use, and more critically, opioid overdose mortality, are poorly understood. In addition, few studies focus on individuals with an OUD diagnosis, a demographic at heightened risk of opioid overdose mortality. Consequently, this study aims to investigate whether changing eligibility criteria, from Medicaid termination to Medicaid suspension, for adults exiting prison with an OUD diagnosis effects opioid overdose mortality risk (OOMR) within 1 year after release. We hypothesize that the policy shift will decrease the probability of post‐release opioid overdose mortality among released individuals diagnosed with OUD.

METHODS

Data Sources

This retrospective cohort study uses administrative records from Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (PADOC) of released adults with an OUD diagnosis between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015 or January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018. PA‐DOC collects data on the state's prison population, which includes demographic, substance use, treatment, and custody characteristics. Personal identifiers (i.e., name [and possible aliases], date of birth, sex, and race) for each individual released during the period of interest were probabilistically linked to death records from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Death Index (NDI). The NDI, a central computerized index of national death records, returns records with probabilistic scores to indicate potential matches of study populations and corresponding death characteristics (date of death, state of death, and causes of death).

Participants

The sample (

n = 5984) included individuals aged ≥18 at release who had an OUD diagnosis and were released from a state correctional institutions (SCI) between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015, and January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018, prior to and subsequent to the suspension of Medicaid throughout imprisonment in Pennsylvania.

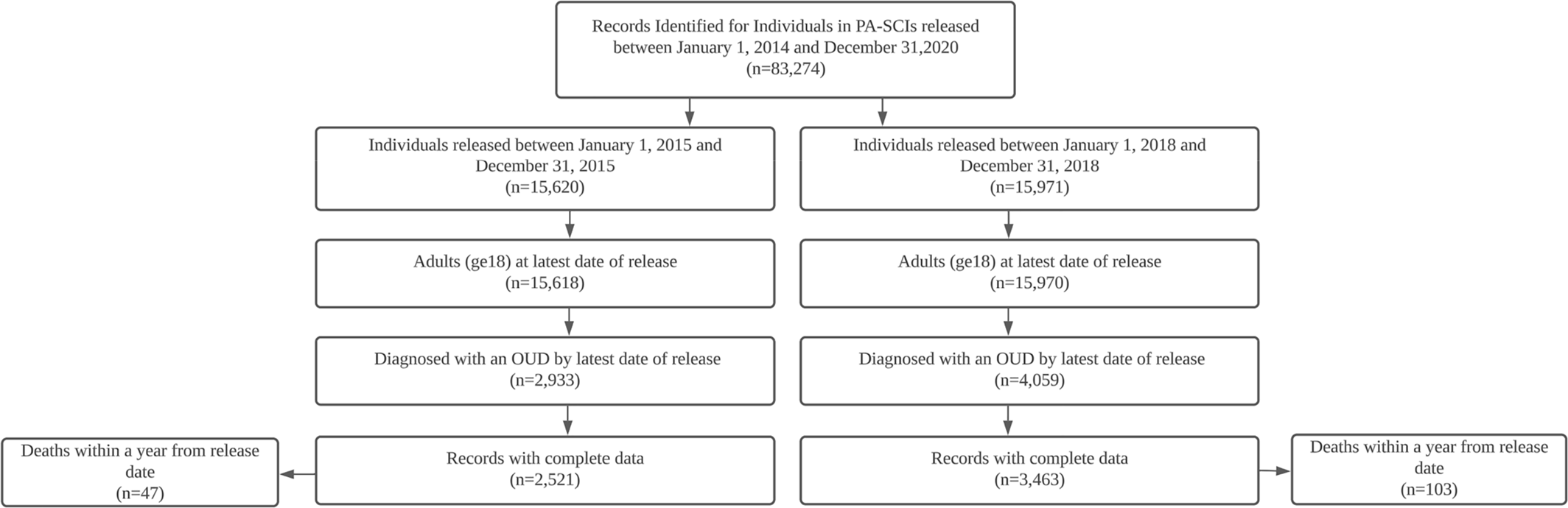

Figure 1 describes how the sample was constructed. The presence of OUD was established using the Texas Christian University Drug Screen II, the screening tool used by PA‐DOC to determine placement and level of care in treatment for those with OUDs and defined as a core score of three or greater—corresponding to a DSM III‐R diagnosis for drug dependency—combined with an opiate listed as any substance of choice. Deaths for individuals with OUD diagnoses (

n = 150) were included when the date of death was within a year of release.

Measurements

The main outcome of interest was death from an opioid overdose. The presence of an opioid overdose death was identified with underlying cause of death (UCD) and multiple cause of death (MCD) codes from the International Classification of Disease Tenth Revision, which is further defined in Supporting Information

S1: Supplement B. Consistent with prior studies (

41,

42), UCDs drug poisoning—irrespective of whether the intent was classified as unintentional (X40–X44), suicide (X60–X64), homicide (X85), or undetermined (Y10–Y14)—were identified in conjunction with the presence of any opioid (MCD: T40.0–T40.4, T40.6). Categorical variables were also created to indicate drug poisonings by type of opioid: T40.0 (Opium); T40.1 (Heroin); T40.2 (natural and semi‐synthetic opioids [i.e., prescription opioids]), T40.3 (methadone), T40.4 (synthetic narcotics, excluding methadone [i.e., fentanyl]), or T40.6 (other and unspecified narcotics). In addition, prescription opioids were identified with MCD codes T40.2 and T40.3. Categories were not mutually exclusive, as deaths may have involved multiple substances, and were developed in correspondence to the methods used in the CDC National Center for Health Statistics.

Qualification for Medicaid suspension was determined by time served within PA‐SCIs, as the department, per state law, had the authority to suspend Medicaid for a period no >2 years. Individuals that served sentences >2 years were deemed ineligible to have their Medicaid benefits suspended throughout imprisonment. Drug‐defined offenses, defined in accordance with definitions from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (

43), were defined as any violations of law that prohibit or regulate the possession, use, distribution, or manufacture of illegal drugs (Supporting Information

S1: Supplement C). Receipt of behavioral health services was defined as admission to a therapeutic community, operated by the state prison system, where care was provided while in detention, irrespective of track, treatment length, level of care determination, whether the participation was a sentence requirement imposed by a judge, or whether the participation was prompted following screening results upon admittance. Medications for opioid use disorder was defined as a Food and Drug Administration approved medication (buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone) provided to an individual with OUD during imprisonment.

Statistical Analysis

Annual frequencies and proportions were calculated for extracted variables from the administratively linked dataset. Frequencies were computed for sex, race, pharmacological treatment, behavioral health service participation, and categorical groupings of age at release, which were then stratified by year of release (2015 vs. 2018). Demographic, treatment, and death characteristics were assessed with bivariate analyses, and multivariable logistic regressions were used to examine the association between qualification for Medicaid suspension and post‐release crude and OOMR, as well as to assess potential risk factors for crude and opioid overdose mortality within a year after prison release. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to compare the mandatory minimum sentence length established by the court compared to actual time served to ensure proper identification of those that qualify for coverage suspension based on correctional length. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4, and significance levels were set at 0.05. The study received approval from the Pennsylvania State University Internal Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample, further described in

Table 1, contained 5984 individuals aged ≥18 who were released from PA‐SCIs with an OUD diagnosis between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2015, or January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2018. The sample was primarily white (77.9%), male (81.5%), and in their 30s (43.5%) at their latest date of release. The mean length of imprisonment was 36.6 ± 36.1 months and, throughout imprisonment, most participated in behavioral health services (62.4%) and few were provided pharmacological treatment (6.1%) and were imprisoned for a drug‐defined offense (26.9%). While PA‐SCIs commonly house fewer transient populations in comparison to other detention facilities, approximately half (49.1%) of the sample qualified for suspension of Medicaid based on time served.

Pooled analyses showed an increased death risk (1.9%–3.0%, p < 0.01) within the year after release, with increased risk of post‐release deaths attributed to opioid overdoses (0.6%–1.7%; p < 0.0001). The primary substance identified in opioid overdoses was synthetic opioids (57.1%–83.1%; p < 0.001). In addition, more individuals participated in pharmacological treatment (0.1%–10.4%; p < 0.001) and less participated in behavioral health services (72.4%–55.2%; p < 0.001) throughout their detentions in PA‐SCIs. Furthermore, more women (16.8% to 19.8%; p < 0.01) and individuals in their 30s with OUD diagnosis (aged 30–39, 39.5%–46.4%, p < 0.001) were released from PA‐SCIs in 2015 and 2018.

Characteristics of Deceased within a Year of Prison Release

Table 2 describes the individuals identified as deceased (

n = 150) within a year of their release in the NDI database. The deceased sample was primarily white (86.0%), male (85.3%), in their 30s (43.5%), and (46.0%) died within 6 months following release. Drug overdose (74.0%) was the leading cause of death within a year of release, which was followed by motor vehicle (5.8%), and cardiovascular disease (3.3%). The most common opioid listed as a contributing cause of a drug overdose was synthetic opioids (78.1%), followed by heroin (13.7%), natural and semi‐synthetic opioids (4.1%), and other and unspecified opioids (4.1%). There were no deaths attributed to methadone or opium within the sample. While most deaths (91.3%) occurred within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, nearly all (98.0%) deaths occurred among states in the east coast of the United States.

Post‐Release Mortality Risk and Medicaid Suspension

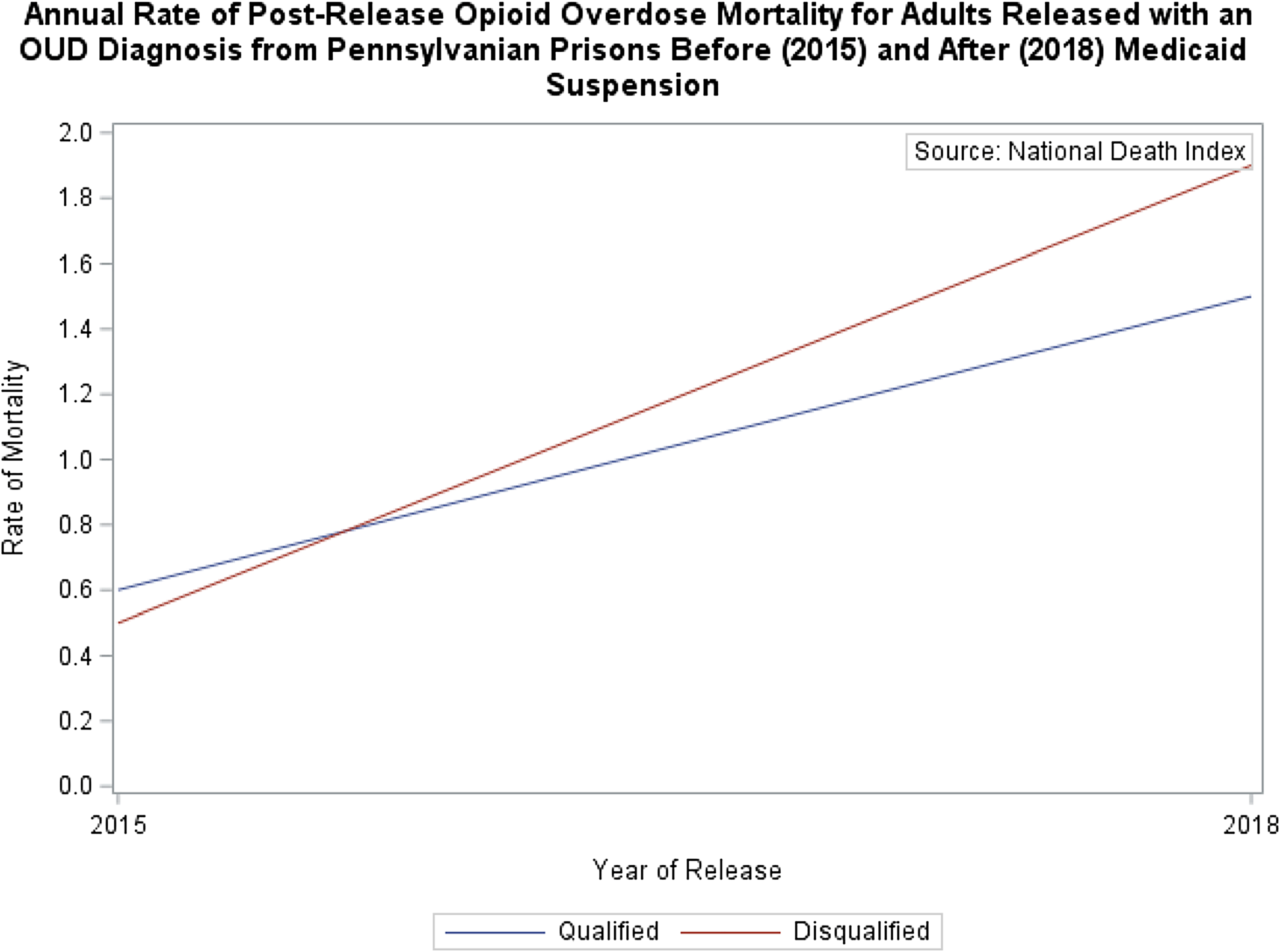

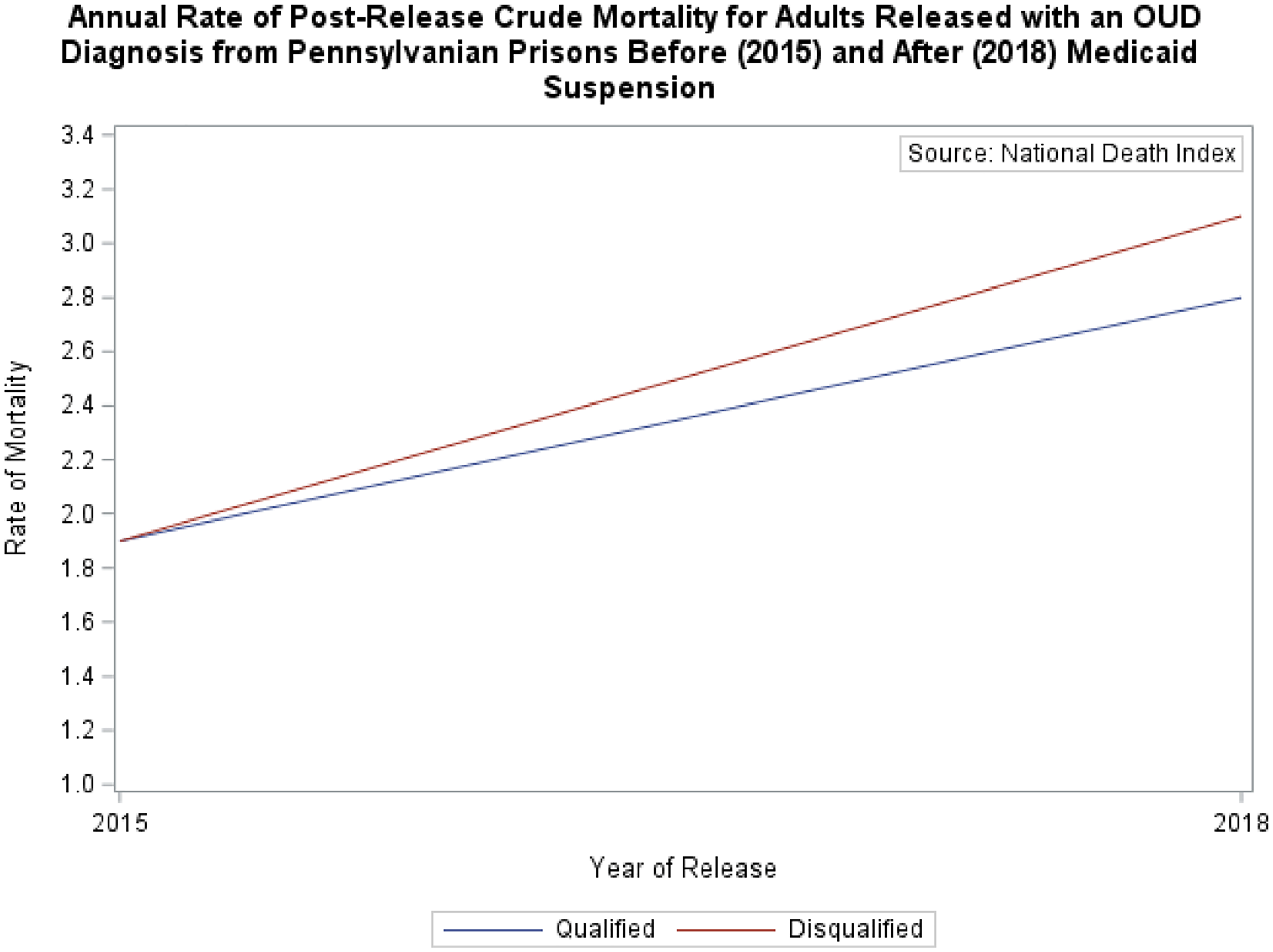

The risk of post‐release mortality, as depicted in

Figures 2 and

3, exhibit fluctuations based on the qualification status for Medicaid suspension among individuals released in 2015 and 2018. In 2015, individuals, whether eligible or ineligible for benefit suspension, exhibited comparable risk of post‐release crude mortality (1.9% vs. 1.9%,

p > 0.05) and opioid overdose mortality (0.6% vs. 0.5%,

p > 0.05) after release from a PA‐SCI. Three years later, following the implementation of Medicaid suspension, despite an overall increase in both post‐release crude mortality and opioid overdose mortality, post‐release OOMR rose at a similar rate among individuals that qualified for Medicaid suspension (0.6%–1.5%,

p < 0.05) compared to OOMR for individuals deemed ineligible (0.5%–1.9%;

p < 0.01), who consequently had their benefits terminated.

Multivariable Logistic Regressions

The results of the multivariable analyses are reported in

Table 3. Few covariates were significantly associated with risk of crude or opioid overdose death, including the primary variable of interest—the interaction between qualification for Medicaid suspension and release in 2018 (OOMR: OR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.47–1.46]; and crude mortality: OR = 1.02, 95% CI [0.67–1.57]). However, the direction of the association is consistent with the hypothesis that suspension of Medicaid is associated with reduced risk of post‐release opioid overdose death for individuals with OUD. In addition, Black race was associated with a statistically reduced risk of crude mortality (OR = 0.44, 95% CI [0.24–0.81)] compared to White individuals, and a release date in 2018 was associated with significantly increased risk of post‐release opioid overdose death (OR = 3.17, 95% CI [1.74–5.77]) in comparison to a release date in 2015.

DISCUSSION

The risk of opioid overdose mortality after release from prison for adults with an OUD increased from 2015 to 2018, particularly from synthetic narcotics, and qualification for Medicaid suspension was not associated with a significant decrease in OOMR or crude mortality within 1 year after prison release for individuals diagnosed with OUD.

Risk of post‐release opioid overdose deaths for individuals with an OUD may be partially driven by the increased presence of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids in the illicit opioid market (

44), as well as limited state harm reduction access (

45,

46,

47). Consistent with prior studies (

1,

6), our study found that drug overdoses have remained the leading cause of death for individuals released from prison and, furthermore, that individuals with a lower risk of post‐release overdose mortality are of black race (

2,

6,

7,

8). In contrast with our findings, other studies have attributed pharmaceutical opioids (

6) and heroin (

2) as the primary opioids implicated in post‐release mortality from opioid overdoses for individuals released from SCI, whereas our findings indicate that synthetic opioids are the primary opioid implicated in post‐release opioid overdose mortalities for individuals with an OUD diagnosis. The change in opioids implicated likely mirrors the evolving pattern of the opioid epidemic, transitioning from prescription opioids to heroin and subsequently to fentanyl.

It is theorized that the mechanisms for which Medicaid suspension influence post‐release opioid overdose mortality is primarily through improvements in OUD treatment participation and treatment continuity (

32,

35,

36,

37,

40), remarkably for treatments that involve agonist and partial agonist medications. These treatments generally lead to reduced illicit opioid use, especially when administered intravenously, thus reducing the likelihood of a fatal opioid overdose after release. The reduced economic strain associated with treatment access through Medicaid, as well as other Medicaid services (i.e. mental health treatment (

31,

32) and treatments (

30,

32,

38)), are likely to assist with mitigation of post‐release opioid overdose risk as well.

Further research is needed to advance understanding of each of these mechanisms involved in post‐release care and their impact on risk of opioid overdose mortality among those released from prison, particularly for more transient prison populations (

6,

48). Since opioid‐related deaths constitute a small percentage of drug overdoses, it's possible the policy was significantly associated with decreases in non‐fatal overdoses after release or improvements in other post‐release outcomes like participation in different treatment services or medical services pertinent to the well‐being of individuals diagnosed with an OUD.

LIMITATIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of a state authorization to suspend Medicaid on opioid overdose mortality in the post‐release period for individuals with an OUD diagnosis; however, there are several limitations that deserve comment. The extent to which these findings can be generalized to other correctional facilities has not been established, particularly with the demonstrated differences in the demographic composition in Pennsylvania SCIs, in combination with the various state approaches to access and insure individuals with Medicaid.

OUD diagnoses were based on a screening instrument that was not confirmed independently, nor do we know the insurance status of released individuals or the departmental efficacies for dissemination of these state policies. The small sample size may have contributed to the failure to reject our null hypothesis, as it is possible that the study lacked sufficient power to detect it adequately, and the identification of opioid‐specific deaths was also limited to the death records provided to the NDI on death certificates. Misclassified or otherwise unknown etiologies, especially on specific drug involvements, may have underreported opioid‐related deaths. However, any misclassifications that may have occurred in the etiologies, should not vary between the groups. In addition, several highly weighted identifiers for data matching (i.e., social security number, state of birth, and state of residency) were not provided by PADOC, which limited probabilistic scores and may have further underreported opioid related deaths.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

The findings underscore the need for ongoing research into overdose prevention approaches tailored for individuals within the criminal justice system, particularly those transitioning from incarceration. Although suspension policies hold promise, comprehensive studies that examine diverse outcomes are essential to determine the true effects of these policies for individuals released from prison. Further research is also crucial to understand the implications across diverse demographic cohorts, notably for individuals with documented concerns of opioid use, evaluate the suitability of implementing Medicaid suspension policies on a broader scale, and determine whether adjustments in implementation are necessary to enhance outcomes after release.