The prevalence of mental illnesses among persons in prisons and jails has been well documented (

1,

2), as have concerns about the treatment and safety of this population (

3–

7). More controversial, however, is the extent to which either mental illness or criminality is the first-order cause of the criminal behavior that results in the incarceration of people with mental illnesses (

8). One view, held by critics of the putative criminalization of people of mental illnesses, argues that symptoms of mental illness motivate criminality and that diversion to treatment rather than incarceration is the appropriate response of the criminal justice system. Such a view results in inequality of punishment—treatment for some and incarceration for others, even for those who committed the same offense. An alternative view is that all people who engage in criminal activities share characteristics, such as drug addiction, poverty, unstable housing, and unemployment, that motivate criminal behavior (

9,

10), and to the extent that people with and without mental illnesses engage in criminal activities for similar reasons, punishment equality, which may mandate incarceration, is appropriate (

11).

Until quite recently, these opposing views were guided by anecdote and advocacy. However, recent evidence suggests that people with mental illnesses who are involved in the criminal justice system share similarities with others involved in the system who do not have mental disorders (

12). Morgan and colleagues (

12) found that inmates with mental illnesses had criminal thinking styles similar to those of inmates without mental illnesses, as well as psychiatric symptoms consistent with psychiatric patients who were not involved with the justice system. Thus treatment approaches need to address mental illnesses and criminality as co-occurring issues (

10,

13,

14), just as treatment has evolved to address co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, which are the most frequently identified co-occurring disorders among persons with mental illnesses (

2,

15).

Methods

Setting

The study population included all inmates housed at ten adult prisons for men and one prison for women within a single state department of corrections. Inmates eligible for the study were those within 24 months of parole eligibility or maximum sentence from the date that the facility survey was conducted. Data were collected between June and August 2009. Excluded from the eligible population were inmates who were housed in the hospital or who were in administrative segregation, halfway houses, or residential treatment units. Also excluded were individuals who were off site on the day of the survey because of court or medical appointments or work assignments. In addition, individuals were excluded if they were being deported, had detainers for new charges, or otherwise had release eligibility dates that were outside the 24-month window (released after June 2011) on the basis of recent parole hearings. Roughly 25% of the initial study population was ineligible for these reasons. In all, 7,622 inmates—three-quarters of the soon-to-be-released population—were eligible to participate. These inmates were invited to participate in a survey about readiness for reentry.

Participants

A total of 3,986 male and 218 female inmates age 18 or older participated in the study, representing roughly 55% of those invited. [A flowchart showing recruitment into the study is available as an online appendix to this report at

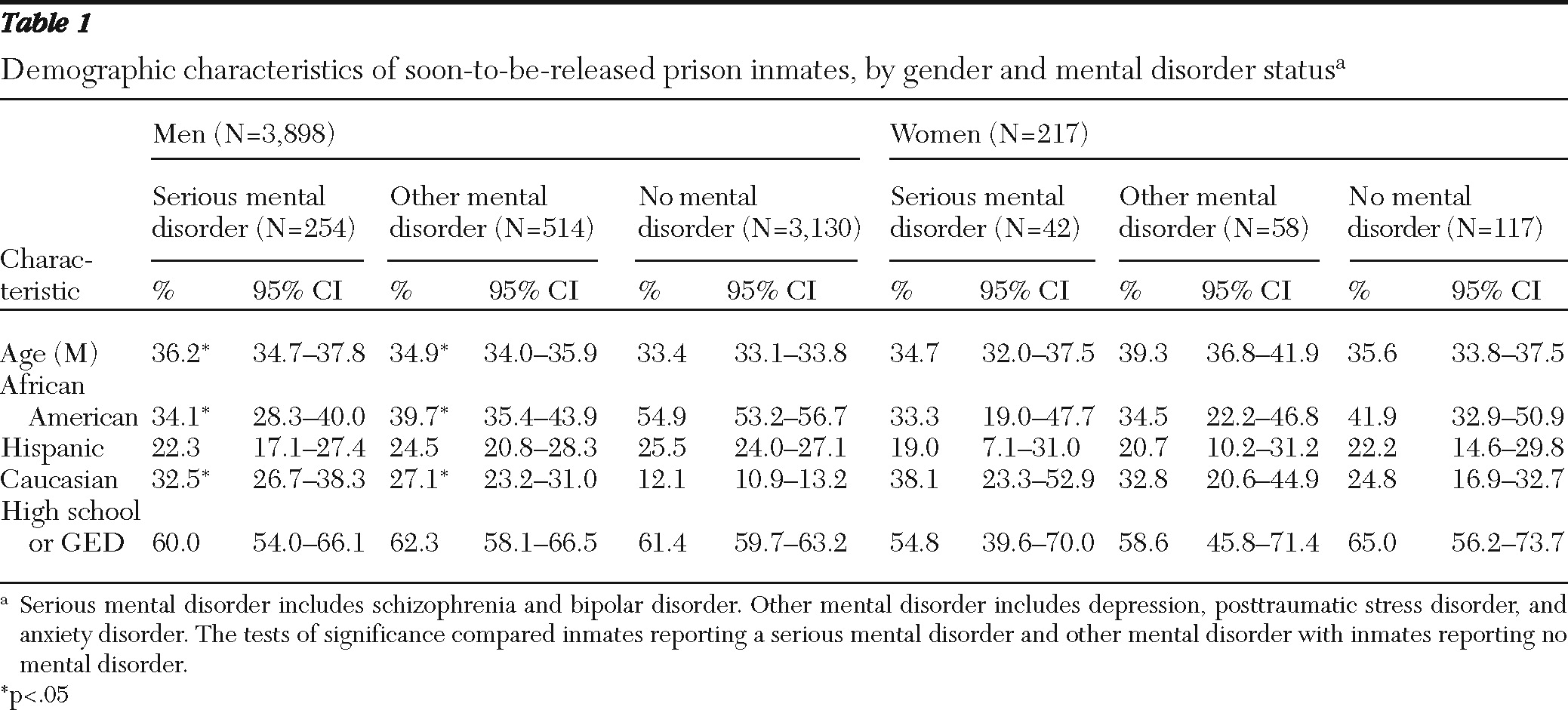

ps.psychiatryonline.org.] Mean±SD ages were 33.3±10.1 for the male inmates and 36.5±10.0 for the female inmates. The demographic characteristics of the sample were similar to those of the general prison population. In the general prison population, 67% of females were nonwhite, compared with 70.5% of nonwhite females in the sample, and female's mean age was 35.4. In addition, 80% of the males in the general prison population were nonwhite, compared with 84.7% of nonwhite males in the sample, and male's mean age was 34.3. Ethnicity and race were conflated in the data reported for the general prison population, and the study sample could not be meaningfully compared. However, 76% of the males in our sample were African American or Hispanic, compared with 78% in the general male prison population. African-American and Hispanic females accounted for 59% of the study sample and 64% of the general female prison population. Data on demographic characteristics of participants are presented in

Table 1. Inmates from racial-ethnic minority groups were underrepresented among male inmates with mental disorders compared with the group without mental disorders.

On average, respondents reported serving three to four years in prison on their current conviction. Among female inmates, the mean±SD years served was 2.7±3.8, and among male inmates it was 3.8±4.8 years. Criminal convictions varied from drug-related offenses to violent offenses. Among the participating inmates, 46% of males and 39% of females reported a drug-related conviction. Among male inmates about 20% were convicted of property offenses and 25% were convicted of violent offenses. Among female inmates about 25% were convicted of property offenses and 20% were convicted of violent offenses. A total of 29 respondents (28 males and one female) were excluded from the analysis because they did not report mental disorder status. For all variables used in this analysis, missing data were less than 3% and were treated as missing completely at random. All means and percentages are based on valid numbers.

Participants were classified as being in the group with serious mental disorders (N=303), other mental disorders (N=579), or no mental disorders (N=3,293) on the basis of their self-reported treatment status while in prison. Individuals in the serious mental disorder group reported treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar spectrum disorders during their incarceration, whereas individuals in the other mental disorder group reported treatment for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or anxiety. Some individuals in the group with no mental disorders reported that they needed mental health treatment (6.2% of males and 8.6% of females); however, they did not report receiving treatment while incarcerated. It is unclear whether their treatment status reflected that they did not meet treatment criteria, treatment was not available, or they did not formally request treatment.

Materials

For purposes of this study, a single survey was developed that included demographic information and the following instruments: Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (

16), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire Short-Form (BPAQ-SF) (

17), and Criminal Sentiments Scale-Modified (CSS-M) (

18). To minimize respondent burden and to maximize the content of the survey, some of the instruments were truncated, either by selecting subscales or using the short-forms of scales. With these adjustments, respondents took, on average, one-hour to complete the survey. Demographic information included basic characteristics (such as age, gender, and race-ethnicity), as well as information regarding criminal history (such as index crime and years of incarceration), behavioral health (such as diagnosis and history of mental health treatment), health (such as current medical diagnosis and current treatment regimen), and problem behaviors (such as hanging out with criminals, getting into fights, and suicidality). With regard to behavioral health, participants were specifically asked about previous treatment (during their incarceration) for schizophrenia; mood disorders, such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder; and PTSD or other anxiety disorders. Positive responses were used to classify respondents as reporting a mental disorder. It should be noted that previous research has shown that participants' self-reported criminal history (

19) and clinical diagnoses are consistent with information in their clinical and criminal records maintained by the prison system (

20).

The BHS is a widely used and psychometrically sound measure of hopelessness (

21). Factor analytic studies of the BHS have consistently produced a three-factor model: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and negative expectations (

21). The BHS is psychometrically sound (

22–

24), and several studies have supported the reliability and validity of the measure (

16,

25). Notably, for purposes of this study, the BHS has been used as a reliable and valid measure of hopelessness with criminal justice populations (

26–

30). For the study reported here, Cronbach's alpha for the BHS was .82.

The BPAQ-SF was used to measure violence, aggression, and anger. It produces a total score and scores on four subscales: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The parent instrument, the BPAQ has been widely used (

31–

33) as a reliable measure of aggression (

32,

34). For purposes of this study, it is important to note that the BPAQ and BPAQ-SF have demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability and validity with correctional samples (

35–

39), including prisoners with mental disorders (

31). Cronbach's alpha for the BPAQ-SF was .89 for this study population.

The CSS-M was used to measure “attitudes, values, and beliefs related to criminal behavior” (

40). It produces a total score and scores on three subscales: law-court-police, tolerance for law violations, and identification with criminal others (

18,

40). The CSS-M has acceptable internal consistency and validity properties (

18) and has been used with offender populations, including offenders with mental illness (

12), to measure antisocial and criminal attitudes (

41–

44). For the study reported here, Cronbach's alpha for the CSS-M was .90.

Procedure

A ten-minute study orientation was provided to small groups of approximately 30 eligible participants. At the conclusion, those interested in participating were asked to provide consent. Written consent was required to participate in the survey. Participants were not compensated for participating. Response rates across all 11 facilities ranged from 46% to 65%, with a mean±SD response rate of 58%±6.9% of eligible participants. The consent procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review board and the Research Committee of the Department of Corrections.

The survey was administered by using audio computer-assisted self-interviews (audio-CASI) and was available in English and Spanish. Participants responded to a computer-administered questionnaire by using a mouse and followed instructions shown on the screen or provided by audio instructions delivered via headphones. Thirty-three computer stations were available, and research assistants were on site to assist participants as needed.

Analysis

Weights were constructed to adjust the sampled population to the full population of the state's prison facilities for different probabilities of selection resulting from different response rates among facilities and nonresponse bias. Base weight is calculated as the reciprocal of the probability of selection, which ensures that each individual in the population has an equal chance of being selected for inclusion in the sample. Final weights were rescaled to reflect the actual sample size (base weight multiplied by sample size and divided by population size). Weighted and unweighted analyses were conducted, and because the results were similar, only weighted results are presented. Means and percentages were estimated on the basis of weighted valid numbers. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) presented in each table are equivalent to two-sided t tests for differences in means or proportions based on Taylor expansion. Analysis of variance for total scores and multivariate analysis of variance for subscales confirmed these results. For ease of interpretation, CIs are presented. SAS, version 9.2, was used for all the analysis, and Proc survey-means was used to construct all statistics and confidence intervals.

Results

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics by mental disorder status and gender. A serious mental disorder (defined as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) was reported by 6.6% (N=261) of the 3,958 male respondents and 13.2% (N=42) of the 217 females. Among males, 19.4% reported depression, PTSD, or other anxiety disorder (other mental disorder); the rate was 26.7% among females. Although major depressive disorder is a serious mental disorder, the information obtained in this study did not allow us to distinguish between major depressive disorder and acute depressive reactions; thus, we opted for a conservative approach and classified all participants who reported depression in the group with other mental disorders.

To check the validity of the mental disorder grouping, responses to a question about need for mental health treatment were examined. For male respondents, 82.9% of those who reported a serious mental disorder and 63.7% of those who reported other mental disorders also reported needing mental health treatment, compared with 6.2% of their counterparts who did not report a mental disorder. Similar treatment need patterns were found for female inmates. A need for mental health treatment was reported by 92.9% of those reporting a serious mental disorder, 79.3% of those reporting other mental disorder, and 8.6% of those not reporting a mental disorder.

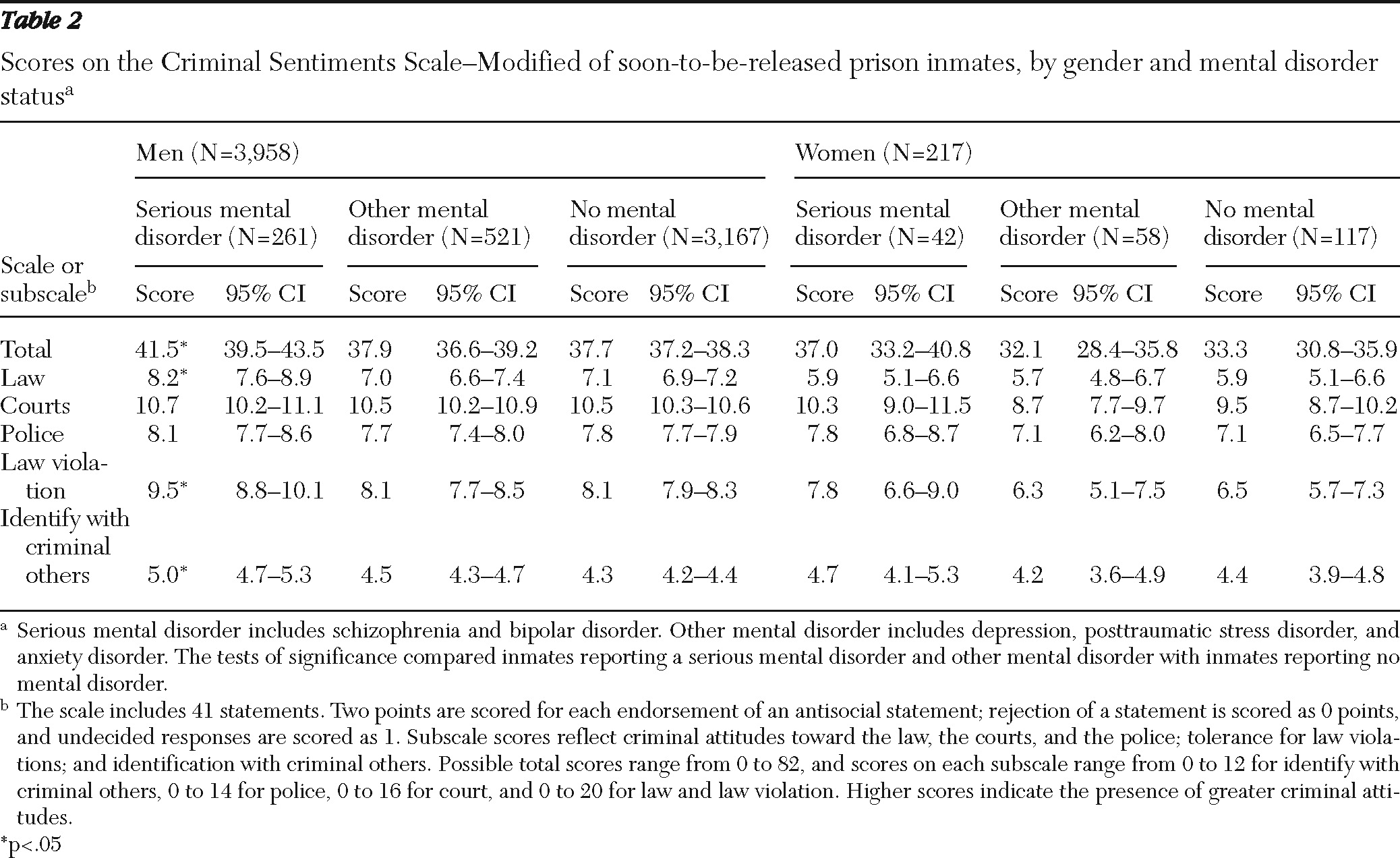

Table 2 presents the mean total and subscale scores for the CSS-M by disorder group. Total CSS-M scores of 30 or more are considered high in terms of criminal attitudes and behavior. The means for all groups (with and without mental disorders) exceeded 30. Total scores were not significantly different between the groups with and without disorders, with one notable exception: scores were significantly higher among males who reported a serious mental disorder than among males who reported no mental disorder. CSS-M subscale scores reflect criminal attitudes toward the law, the courts, and the police; tolerance for law violations; and identification with criminal others. Subscale scores were similar for respondents with and without a reported mental disorder; however, males who reported a serious mental disorder had higher scores on criminal attitudes toward the law, tolerance for law violations, and identification with criminal others compared with males who did not report a mental disorder.

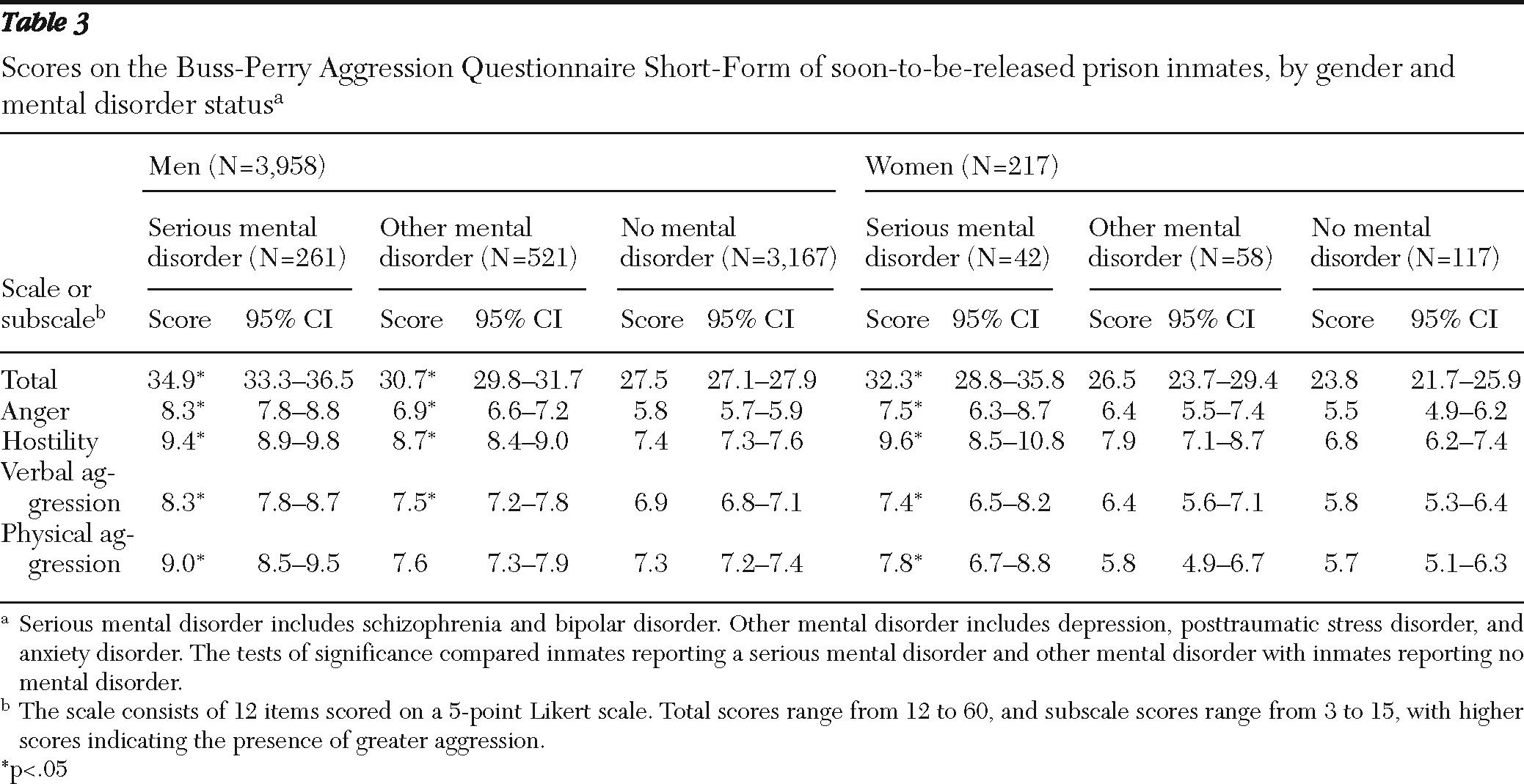

Table 3 shows results for the BPAQ-SF. Both males and females who reported a serious mental disorder scored significantly higher overall and on each of the four dimensions of aggression than their counterparts without a reported disorder. Males who reported other mental disorder scored significantly higher overall and on each of three dimensions of aggression than their counterparts without a reported disorder (the exception was physical aggression).

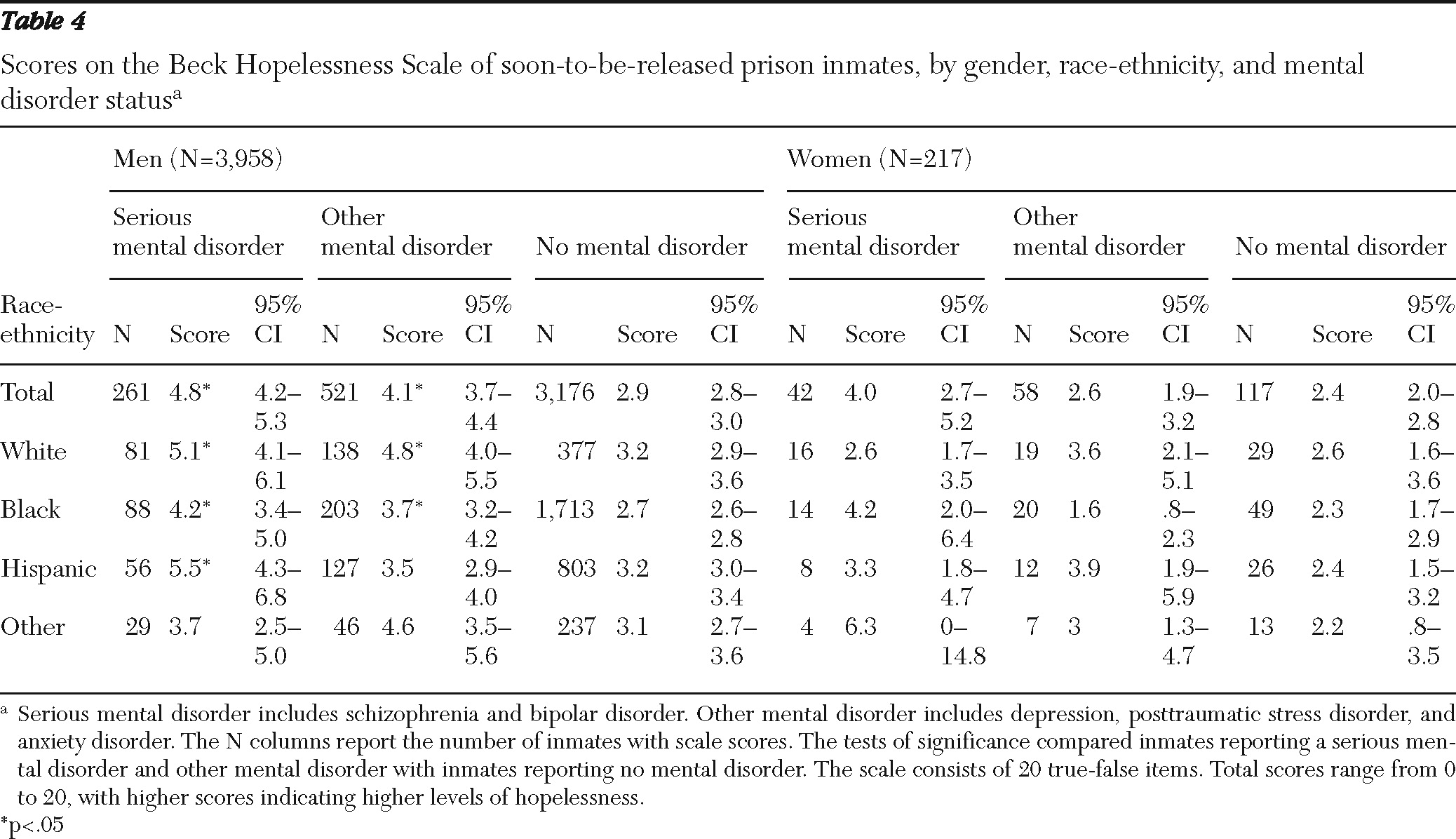

Results for the BHS are shown in

Table 4. On average, hopelessness scores were in the range of minimal (total score <3) to mild (total score 4 to 8) for males and females. However, levels of hopelessness were generally higher for male inmates with a reported mental disorder and highest for males with a reported serious mental disorder. These differences were statistically significant for all males, white males, and African American males with a reported serious or other mental disorder, and for Hispanic males with a reported serious mental disorder. Patterns of hopelessness were less consistent for females, likely, in part, because of the smaller sample size.

As shown in

Table 5, the patterns in criminal attitudes and feelings of aggression and hopelessness among incarcerated persons reporting a serious mental disorder, other mental disorder, or no mental disorder were consistent with participants' reports of previous problems with behaviors associated with criminogenic risks, aggression, and depression. With the notable exception of “hanging out with people involved in crime” and “gambling,” male inmates who reported either a serious or other mental disorder were more likely than their counterparts who did not report a disorder to report behaviors of criminality, aggression, and depression. Differences in this regard were also found by disorder status for female inmates, but these differences less frequently reached significance because of the smaller sample; however, female inmates who reported a serious mental disorder had significantly higher rates of some of the behaviors than female inmates who did not report a disorder.

Discussion

This study examined similarities and differences in criminal thinking styles and feelings of aggression and hopelessness of male and female inmates by mental disorder status. Consistent with Morgan and colleagues (

12), we found that inmates who reported a mental disorder evidenced antisocial attitudes similar to or greater than those who did not report a mental disorder. In fact, consistent with findings that antisocial personality disorder is associated with schizophrenia (

45), males who reported a serious mental disorder scored higher than those who did not report a disorder on most of the CSS-M scales. Although female inmates who reported a mental disorder did not score statistically higher on subscales of the CSS-M, their scores were consistent with female inmates who did not report a mental disorder. Anger is also a risk factor for criminal acts (

46–

48), and consistent with the results for antisocial attitudes, male inmates who reported a serious or other mental disorder scored significantly higher on a measure of aggression, including the four primary BPAQ-SF subscales of anger, hostility, verbal aggression, and physical aggression. For females, these BPAQ-SF findings were limited to those who reported a serious mental disorder.

The BHS scores of male and female inmates who reported a serious mental disorder, as well as male inmates who reported other mental disorders, were in the clinically significant (albeit mild) range of hopelessness. Levels of psychological disturbance were significantly greater among inmates who reported mental disorders than among those who did not report a mental disorder.

Several limitations warrant mention. First, diagnostic information was based on self-report. Validating the diagnoses with diagnostic instruments would be ideal but was not feasible. Research has found, however, that offenders tend to accurately report historical crime-related information and thus are likely to report accurate psychiatric information (

49). The reported need for mental health treatment in our study was consistent with the diagnostic groupings (the highest need was reported by those who reported a serious mental disorder); however, validity remains uncertain. For this reason and because some mental disorders are chronic whereas others are acute, use of an indicator of mental disorder based on self-report of prior treatment for a specific mental disorder during incarceration may not accurately measure “current” mental disorder. To address this issue, we separated mental disorders into serious and other to distinguish among disorders that are known to be more persistent (such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) and those that change over time (such as depression and anxiety). Inmates with serious mental disorders who did not seek treatment during incarceration would have been categorized as not reporting a mental disorder, which may have biased the group with no reported disorders toward patterns found for the group with serious mental disorders.

Second, sample bias is possible. It is not known whether or how inmates who refused to participate in the study differed from participants. Nonrepresentativeness of the sample was tested in terms of gender and age and adjusted for in the weighting strategy, which may not have fully accounted for the differences between the sample and the population. We accounted for this uncertainty by estimating CIs that provide a reasonable (95%) approximation of the range of variation for the measures. Third, biased reporting may have occurred. Audio-CASI is the most reliable method of collecting information about activities or events that are shaming or stigmatizing. By using audio-CASI, we minimized inmates' motivation not to reveal a mental disorder. To limit monomethod bias among respondents, we used standardized instruments (CSS-M, BPAQ-SF, and BHS) that have strong psychometric properties. Also, we provided data on behaviors related to the constructs of criminal thinking, aggression, and hopelessness and which showed consistent behavioral patterns across the disorder status groups.

Given these limitations, our findings are confirmatory of findings by Morgan and colleagues (

12) but certainly not conclusive. They do, however, inform and advance our understanding of the treatment needs of persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system with mental illnesses. Our findings, in combination with those from earlier studies, suggest the need to tailor interventions to the co-occurring criminal risk and mental health needs presented by this population. Specifically, the evidence does not support a dichotomous view of the issues of criminality and mental illness, with treatments tailored to address one or the other issue. Rather, greater success is likely to be obtained when interventions are developed to treat the co-occurring issues of criminality and mental illness. Some limited progress is being made in this regard. Skeem and colleagues (

50) have shown, for example, that a service-oriented approach (that is, developing a collaborative relationship built on respect and care for the offender) significantly improves outcomes for offenders with mental illness in community supervision. Similarly, Draine and colleagues (

51) developed an innovative and comprehensive multidisciplinary treatment team model integrating criminal justice, mental health, and social service professionals to facilitate the community reentry of inmates with mental illnesses who are released from prison. Citing stigma and other barriers to recovery (such as homelessness and difficulties obtaining work), Draine and colleagues (

51) advanced the notion that it is the service provider's responsibility to identify and bring together community-based resources and broker relationships between the returning citizen (former inmate) and society. They argue that reintegration occurs and the likelihood of recidivism declines when a returning citizen believes he or she is part of the broader, law-abiding society. Greater understanding of criminal antecedents, such as criminal thinking, will likely improve the outcomes from these services.

There is a growing body of evidence showing that persons with mental illnesses who are involved in the criminal justice system have behavioral and thinking styles similar to those of justice-involved persons without mental illnesses. Although little is known about effective therapeutic strategies for this population, it is often postulated that strategies that have proven beneficial for treating criminality in the general population may also prove beneficial with persons with mental illnesses whose criminal behavior has similar etiology (

52). The results of this study support Draine and colleagues' (

10) recommendation to integrate crime theory into mental health services for persons involved in the justice system. However, too few interventions are being developed, and much more research is needed here.

Our failure to respond therapeutically to co-occurring mental illness and criminally oriented thinking and feeling neglects primary risk factors associated with recidivism (

9). Attention to these factors is particularly important given the need to match treatment programs with the needs of persons with mental illnesses involved in the justice system (

53). Researchers, however, have not empirically investigated these issues, and there is thus a dearth of evidence-based treatment programs in correctional settings (

54).

In developing the next generation of interventions to prevent the involvement of persons with mental illnesses in the criminal justice system, it behooves us to begin by relaxing the assumption that people with mental illnesses are involved in the justice system simply as a result of their mental illness. Rather, these individuals may also present the characteristics and antisocial attitudes common to persons without mental disorders involved in the justice system. Antisocial cognitions are an independent risk factor for criminal recidivism. Future studies are needed to determine whether cognitive change programs that have proven effective in the general offender population are useful for justice-involved persons with mental illnesses.