Antipsychotic agents have been a cornerstone of effective treatment for schizophrenia. Some also have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute mania, maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder, treatment of irritability associated with autistic disorder, and adjunctive treatment of major depression. In addition to their indicated use, off-label prescribing of antipsychotics is common (

1–

4). Since 2005, sales of antipsychotics have consistently ranked among the top three therapeutic classes and surpassed the lipid-lowering agents and proton pump inhibitors in 2009 to become the top-selling class in the United States, with $14.6 billion in sales (

5).

However, antipsychotic medications are associated with significant risks. First-generation antipsychotics produce serious extrapyramidal side effects, such as akathisia, tardive dyskinesia, or drug-induced parkinsonism. Second-generation antipsychotics have reduced propensity to cause these side effects but are associated with metabolic abnormalities, such as weight again, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and diabetes (

6,

7). The risk of life-threatening complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis led to an FDA black-box warning for all second-generation antipsychotics in 2003 (

4). Although most attention has been given to the metabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotics, many first-generation antipsychotics also can cause substantial weight gain (

8). In 2004, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), American Psychiatric Association (APA), and several other professional organizations issued consensus statements regarding metabolic risk of antipsychotics and recommended optimal monitoring and management schedules for these side effects (

6).

Antipsychotics differ in their risk of causing metabolic abnormalities, with clozapine and olanzapine posing the highest risk (

6–

10). When choosing among antipsychotic agents, the ADA/APA consensus statement recommends that “the likelihood of developing severe metabolic disease should be an important consideration” and that switching to an antipsychotic agent with lower metabolic risk should be considered when a patient develops a metabolic abnormality (

6). However, little is known regarding the extent to which preexisting metabolic risk factors are taken into consideration in providers' decision making to prescribe or continue an antipsychotic agent.

Using data from the 2005–2007 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), we examined the association between patients' preexisting metabolic risk (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, or hypertension) and the propensity of the received antipsychotic agents to cause metabolic side effects during an office-based physician visit. According to the consensus recommendations, we hypothesized that patients with higher metabolic risk are more likely to receive antipsychotics with lower propensity to cause metabolic side effects.

Methods

Data source

The NAMCS is an annual probability survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and is designed to generate nationally representative estimates of visits to nonfederal, office-based physicians providing direct patient care in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Physicians surveyed in the NAMCS are selected through a multilevel sample selection process, and those who respond are then randomly assigned to one of 52 weeks in a year and report information on a systematic random sample of patients treated during that week (

11). Details on the sampling and estimation process are available at the NCHS Web site (

www.cdc.gov/nchs).

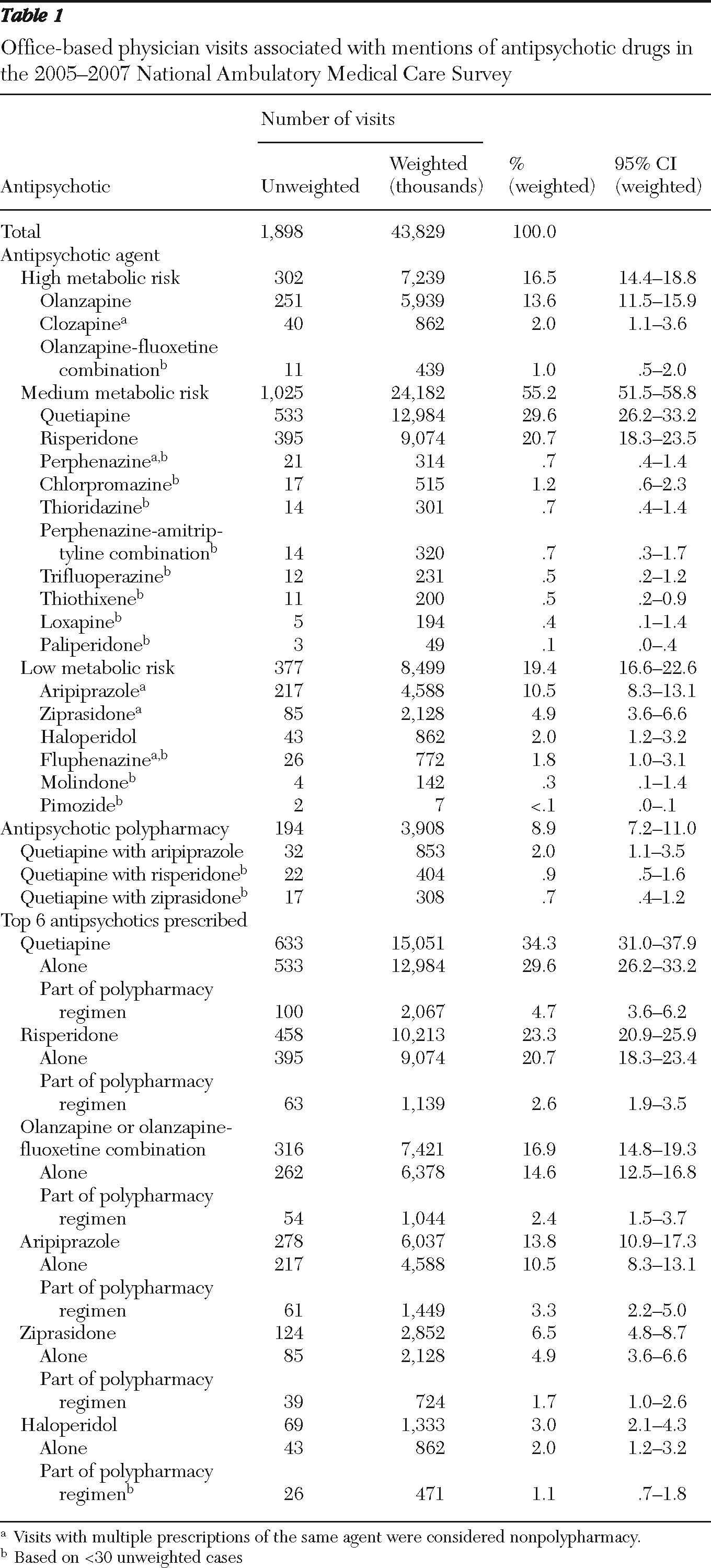

Antipsychotic drug visits

We included all office-based physician visits during which antipsychotics were mentioned. These visits were referred to as “antipsychotic visits” regardless of the reason for the visit. The NAMCS reports up to eight medications ordered, provided, or continued during a visit. Drugs were classified via Multum Lexicon therapeutic categories, a proprietary database of all prescriptions and some nonprescription drug products available in the United States (

11). Before 2006, the NAMCS used a system developed by the NCHS as well as the FDA's

National Drug Code Directory to classify medications. To be consistent with later years, we applied the mapping file provided by the NAMCS to match drug codes used in 2005 with the corresponding 2007 Multum codes for generic composition of the medications and their corresponding therapeutic categories (

11). Antipsychotics identified through this process included aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, clozapine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, loxapine, molindone, olanzapine, perphenazine, pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, thioridazine, thiothixene, trifluoperazine, and ziprasidone. We excluded prochlorperazine because it is used mostly as an antiemetic (

2). Mesoridazine and chlorprothixene were not present in the NAMCS 2005–2007 data. We pooled data from the three years to increase estimation precision. A total of 1,898 antipsychotic visits were identified.

Metabolic risk category of antipsychotics

Antipsychotics mentioned during the visits were classified as having high, medium, or low risk of causing metabolic abnormalities (see box on this page). These metabolic risk categories for second-generation antipsychotics were derived from the 2004 ADA/APA consensus statement (

6), with the exception of paliperidone, which was added to the medium-risk category on the basis of a recent review (

12). Categories for first-generation antipsychotics were derived from findings from a comprehensive review article on their risk of causing weight gain (

8) and with consensus of two investigators (RRO, DM). Findings from the CATIE study (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) were used to place perphenazine in the medium-risk category (

13). A separate category for antipsychotic polypharmacy was specified for visits in which multiple antipsychotics were mentioned.

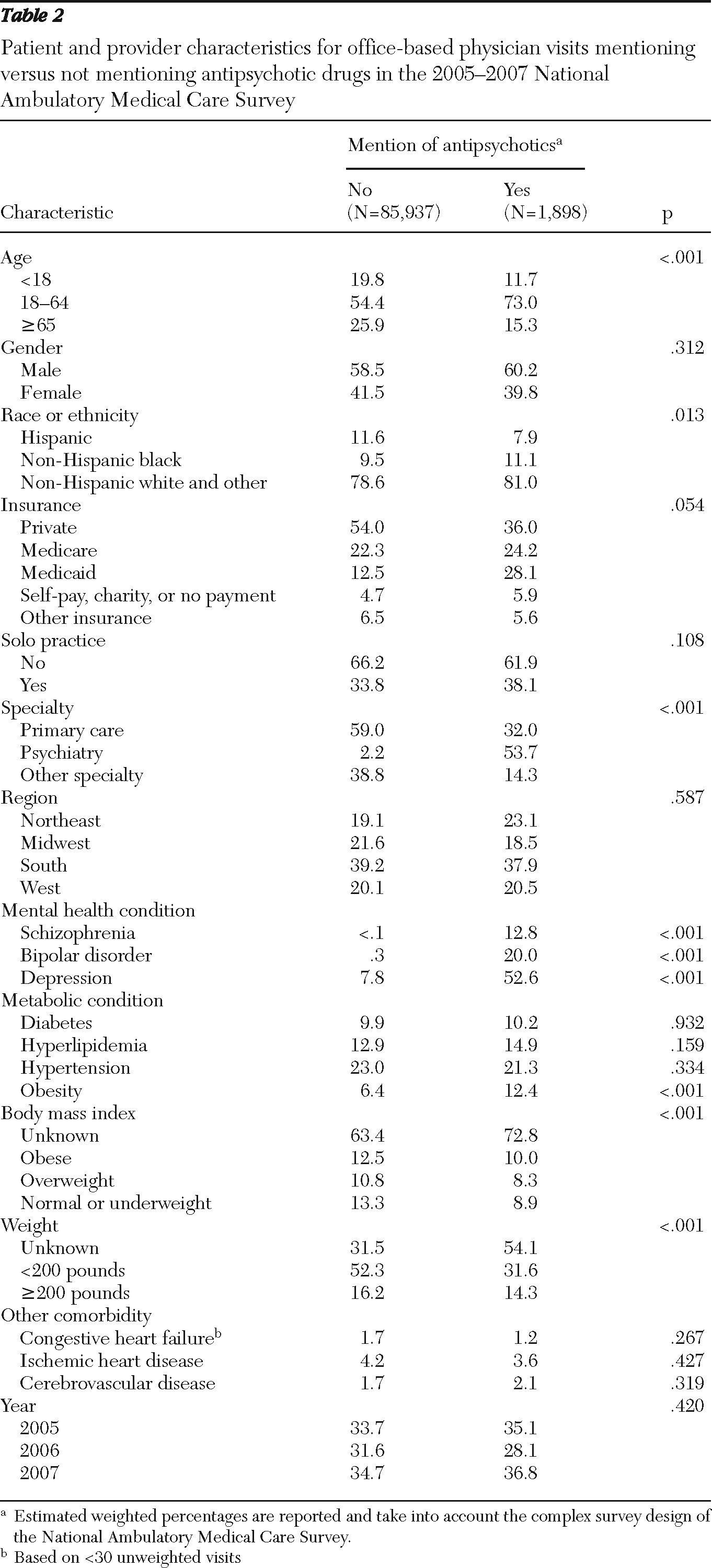

Key independent variables

Patients' preexisting metabolic risk was assessed by the presence of the following comorbid conditions: diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and hypertension. Using

ICD-9-CM codes, the NAMCS records up to three diagnoses per visit. The following

ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify these conditions: diabetes, 250.XX; hyperlipidemia, 272.0X–272.4X; obesity, 278.0X; and hypertension, 401.XX–405.XX. In addition, the NAMCS asks respondents to select from a checklist of common chronic conditions (including the aforementioned conditions) that a patient may have regardless of the diagnoses assigned during the visit (

11). For this study, a patient was considered to have one of the conditions if either a relevant diagnosis codes was assigned for the visit or if the condition was selected via the checklist.

In addition, the NAMCS reports body mass index (BMI) for all patients except pregnant females or patients under two years old. This variable was used to provide an alternative definition of obesity. We classified BMIs of adults (age 18 or older) into three categories according to World Health Organization criteria: obese (≥30.00), overweight (25.00–29.99), and normal to underweight (<25.00). For children ages two years to 17 years, obesity and overweight were determined on the basis of the BMI-for-age growth charts developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which take into account body fat changes typical with age, as well as gender differences (14). BMI was then translated into a percentile for a child's sex and age and categorized as follows: obese, ≥95th percentile; overweight, ≥85th percentile and <95th percentile; and normal or underweight, <85th percentile) (

14). Visits with missing BMIs were classified into a separate group.

Other covariates

Other covariates included patient demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race or ethnicity), payment type (private, Medicaid, Medicare, uninsured, and other), mental health conditions (schizophrenia, ICD-9-CM code 295.XX; bipolar disorder, code 296.0X, 296.1X, or 296.4X–296.8X; and depression, code 296.2X, 296.3X, 311.XX, or 293.83 or selected via the checklist), other comorbidities (congestive heart failure, code 428.XX or selected via the checklist; ischemic heart disease, code 410.XX–414.XX or selected via the checklist; and cerebrovascular disease, code 430.XX–438.XX or selected via the checklist), and physician characteristics, which included solo practice (yes or no), physician specialty (primary care, psychiatry, or other specialties), and geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Also, dummy variables for years 2006 and 2007 were included to evaluate changes over time.

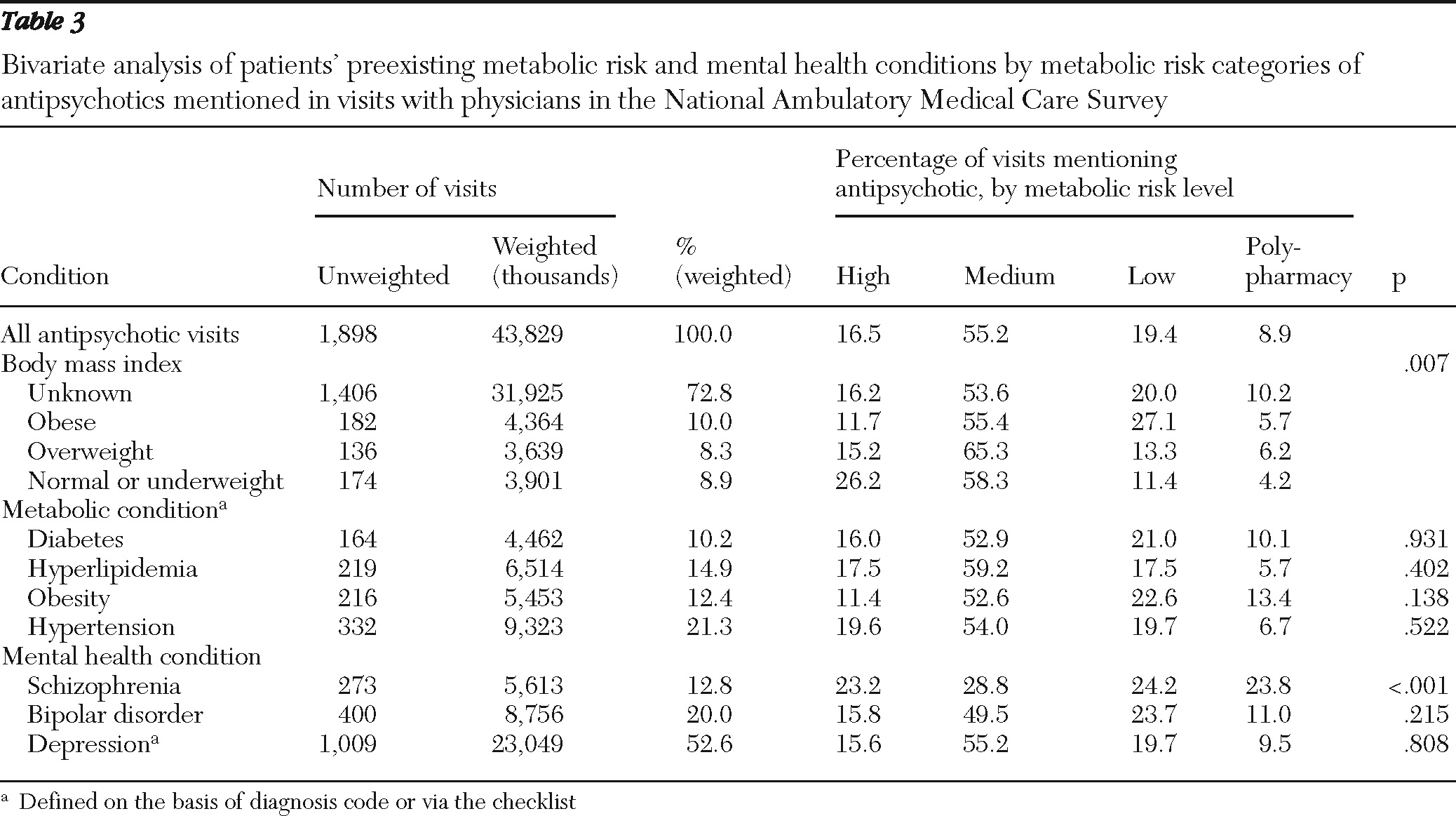

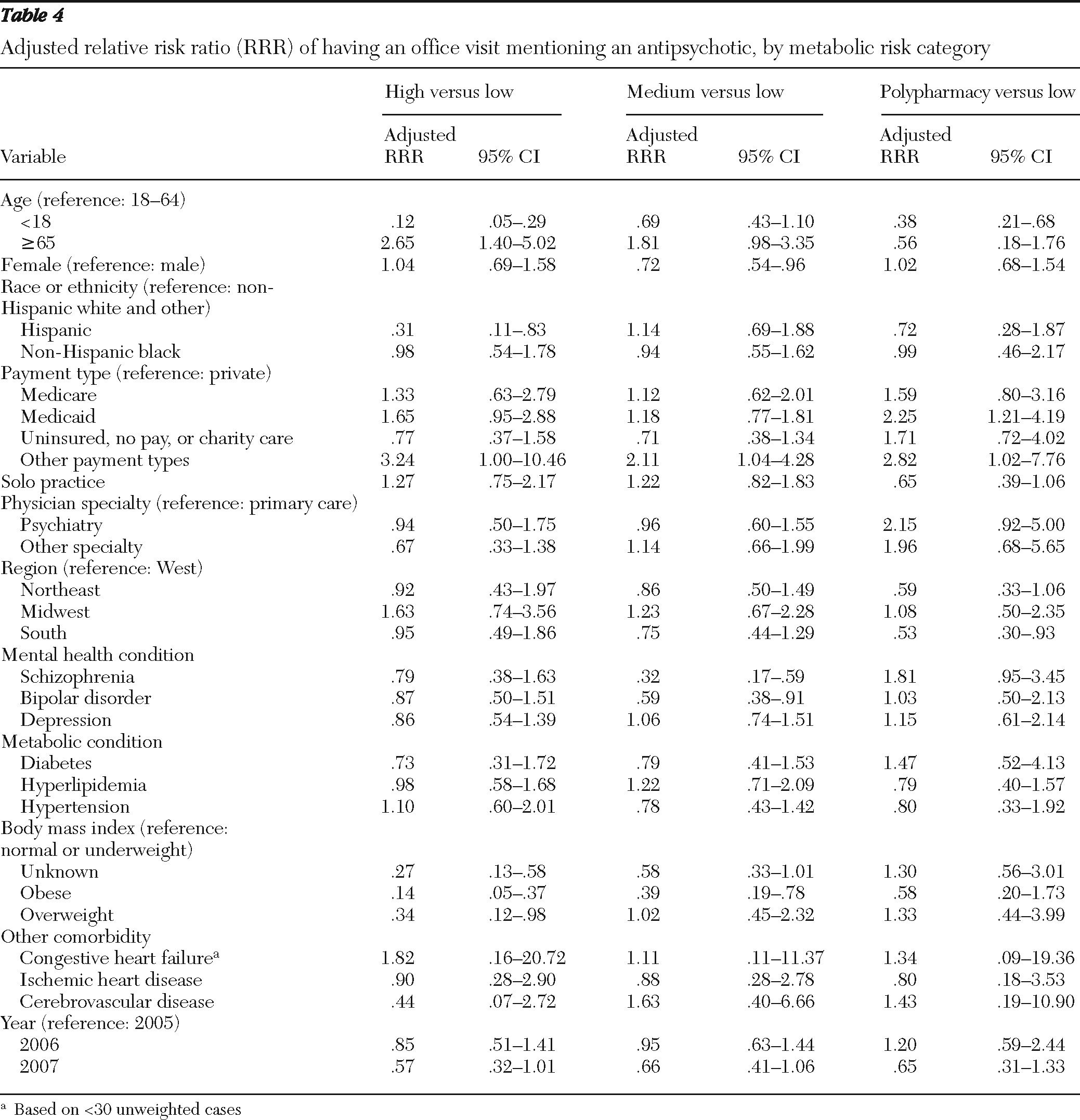

Data analysis

Patients' preexisting metabolic risk was compared across the metabolic risk categories of antipsychotics; we used adjusted Wald tests for continuous variables and design-adjusted Pearson chi square tests for categorical variables. Because the dependent variable—the metabolic risk of antipsychotics—was defined at four levels (high, medium, or low risk or polypharmacy), we used multinomial logit (MNL) regression models to examine the association between this variable and patients' preexisting metabolic risk, controlling for other covariates listed above. Separate regression analyses were conducted with the BMI categories or an indicator for obesity defined on the basis of physicians' diagnoses or via the checklist.

All analyses were conducted with SVY commands in Stata 9.2 to take into account the complex sample survey design of the NAMCS. The standard errors were calculated with Taylor-series linearization approximation (

15). Statistical significance was determined at p<.05. As advised by the NAMCS, estimates based on fewer than 30 unweighted cases or with standard errors greater than 30% of the estimated values were considered statistically unreliable (

11) and are denoted in our tables.

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that in a representative national sample of physicians, obese patients were more likely to receive or continue antipsychotics with lower risk of causing metabolic abnormalities during an office visit. This finding suggests that the patient's weight may be a key consideration when providers make decisions to order antipsychotic medication with lower metabolic risk or to continue an antipsychotic medication. However, having preexisting metabolic conditions, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension, appeared to have little effect on physicians' choice of antipsychotics with regard to their metabolic risk properties, even after we controlled for patient and physician characteristics, including patients' psychiatric diagnoses. One possible explanation is that these conditions often occur together and with obesity among patients receiving antipsychotics (

16–

18); thus including these metabolic conditions in the same model with BMI categories or the obesity indicator may mask their effects. However, separate regression analyses with each of these three conditions as a predictor variable without the BMI or obesity indicator variables did not show statistically significant effects for these variables.

Another plausible explanation for lack of association between these metabolic conditions and antipsychotic choice may be that psychiatrists, who accounted for 54% of antipsychotic visits, may be less aware than other providers of patients' metabolic comorbidities. A significantly higher number of antipsychotic visits to psychiatrists were missing BMIs (89% versus 54% in other visits). In addition, metabolic comorbidities were reported less frequently during these visits compared with visits to other providers, even though these conditions co-occur more frequently among patients with schizophrenia than in the general population (

16–

18). To check this possible explanation, we ran separate regressions stratified by specialties and found that the association between BMI levels and antipsychotic risk category was statistically significant for only primary care physician visits. Regression analysis including only primary care physician visits also found significantly fewer mentions of high-risk antipsychotics compared with low-risk agents for patients with diabetes. However, this result was sensitive to model specification and should be further explored with other databases.

Our findings are contrary to the report by Dassori and colleagues (

17), who found that preexisting diabetes was associated with an increase in second-generation antipsychotic switching from an agent with higher metabolic risk to one with lower risk among older veterans with schizophrenia but obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were not (

17). That study focused on a patient population (older veterans with schizophrenia), study periods (2002–2003 and 2004–2005), and study design (prescription changes over two time periods) different from ours, which may account for the different findings. However, even in their study, switching to antipsychotics with lower metabolic risk occurred among only 1.5%–6.0% of patients despite the high prevalence of comorbid metabolic conditions in this cohort (15%, 24%, 34%, and 45% of patients with obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, respectively), suggesting that switching to antipsychotics with lower metabolic risk in the presence of these comorbidities is rare. Such switching patterns may arise from concerns of clinicians, patients, and sometimes caregivers regarding worsening psychiatric symptoms or tolerability (

19). This consideration may be particularly important for patients with schizophrenia because changes in treatment have been found to be associated with increased acute-care service use and higher annual health care costs (

20). Nonetheless, among those switching from one second-generation antipsychotic agent to another due to adverse events, weight gain was more often the reason than other adverse events (

21).

Metabolic risk categories of antipsychotics used in this study were derived largely from findings on risk of weight gain (

6,

8), which may partially explain the sensitivity to weight abnormality but not other metabolic risk parameters examined in this study. Weight gain is the most widely studied adverse effect of antipsychotics; findings in the literature regarding the risk of weight gain for various antipsychotic agents were generally consistent (

6,

7). However, the risk of dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus has been less studied and is more controversial (

6,

7). Growing evidence shows that medications for diabetes or hyperlipidemia, such as metformin or statins, were effective in treating and preventing antipsychotic-induced weight gain and other metabolic abnormalities (

22–

24). If patients with diabetes, dyslipidemia, or both conditions experienced no worsening of their glycemic or lipid control with appropriate treatments, continuing an antipsychotic in the higher-risk category may be clinically justifiable.

Several limitations of this study should be recognized. First, this study was cross-sectional. For continuous users of antipsychotics, we were not able to observe previous clinical response to these treatments or medication tolerance and therefore could not determine whether not switching to antipsychotics with lower metabolic risk was due to positive treatment response to a higher-risk agent. Also, providers may weigh the importance of a patient's preexisting metabolic risk differently depending on whether a new antipsychotic regimen is needed. As a sensitivity analysis, we stratified visits by mentions of any newly prescribed antipsychotics; the metabolic risk categories of antipsychotics mentioned during visits with a change in antipsychotics and visits with only continued use of antipsychotics were not statistically significantly different. Therefore, no further distinction was made in this study. However, only 10% of antipsychotic visits had mentions of any newly prescribed antipsychotics, which may explain the lack of statistical significance. Larger databases are needed to further explore this issue.

Also, the NAMCS is nationally representative of visits rather than patients. It is possible that a sample patient may be counted more than once in the data if he or she visited different physicians (for example, a primary care physician and a psychiatrist) included in the sample. However, the chance of this occurring is low given that physicians were randomly assigned to one of the 52 weeks in a year and reported visits during only that week.

A large number of visits were missing BMI or weight measurements, which was more common for visits to psychiatrists. Providers for antipsychotic visits with available BMI or other weight measures may be more aware and concerned about metabolic risk of antipsychotics. Thus our results may overstate the importance of weight when choosing among antipsychotic medications with different metabolic risk. However, using an indicator for obesity based on physician diagnoses and on reported preexisting conditions or body weight over 200 pounds resulted in findings consistent with the analysis using BMI.

Moreover, our classification on the basis of the associated metabolic risk of antipsychotics did not consider the actual doses and serum concentration of these agents, neither of which is reported in the database. A recent study showed that compared with higher doses of quetiapine for patients with major depression, lower doses may have lower risk of metabolic abnormalities (

25), suggesting that our current categorization without considering doses could have misclassified the metabolic risk of some antipsychotics taken at lower doses.

Only up to eight medications per visit are recorded in the NAMCS. Antipsychotic polypharmacy was defined as prescriptions of multiple antipsychotic agents during the same visit. This definition may have misclassified the cross-titration during antipsychotic switching as polypharmacy. As a sensitivity analysis, we reanalyzed our data by assigning polypharmacy visits to the highest-risk category of all antipsychotics mentioned during the visit and found results consistent with our previous results. Long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy (≥60 days) may have higher metabolic risk (

26), but that could not be assessed in this data set because of its cross-sectional nature.

At the time of this study, 2007 was the latest year with available data. The years reviewed (2005–2007) may have been too soon after the 2004 ADA/APA recommendations to have observed significant changes in prescribing patterns. Future studies using more recent data are needed to track the changes.