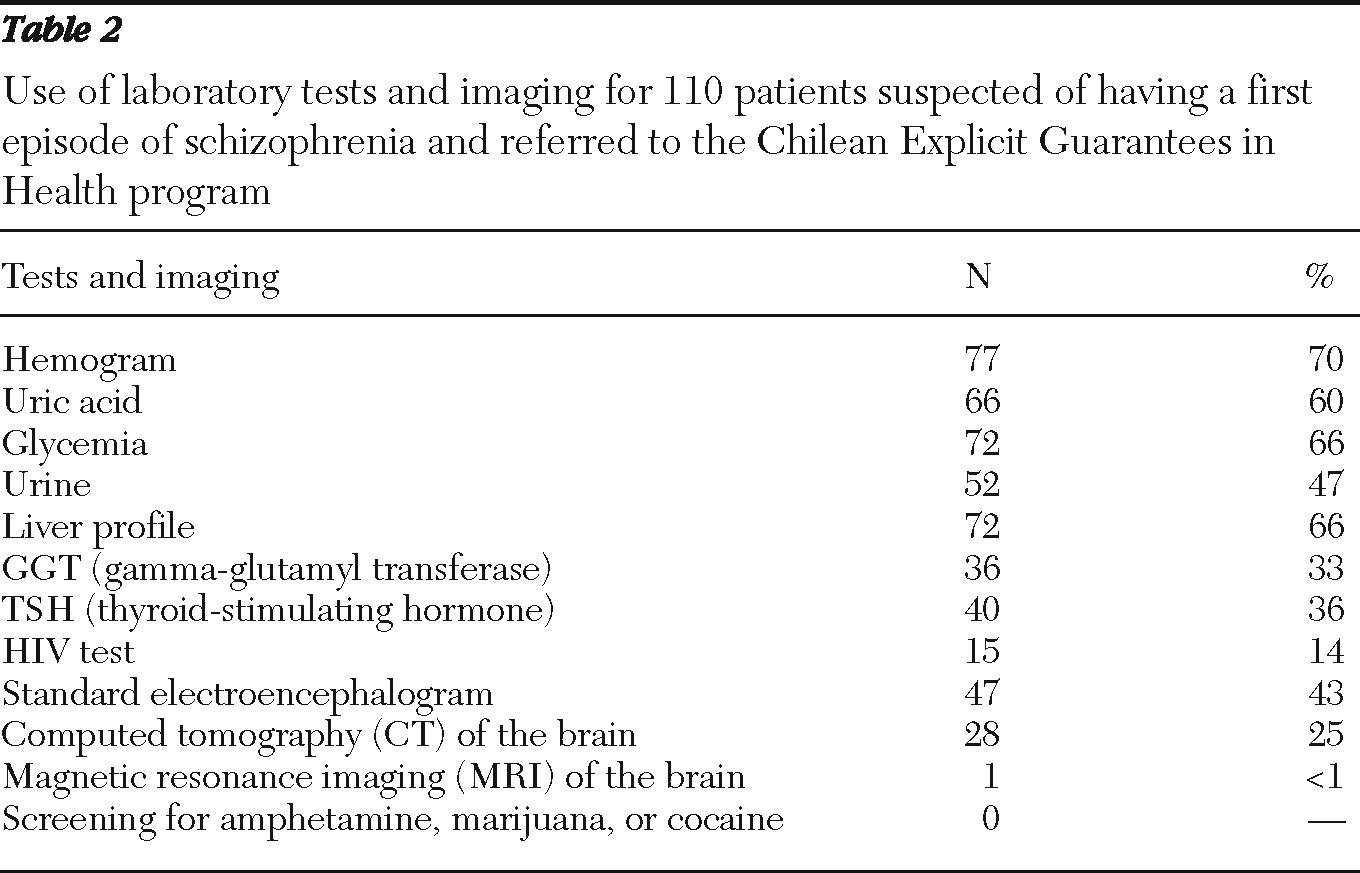

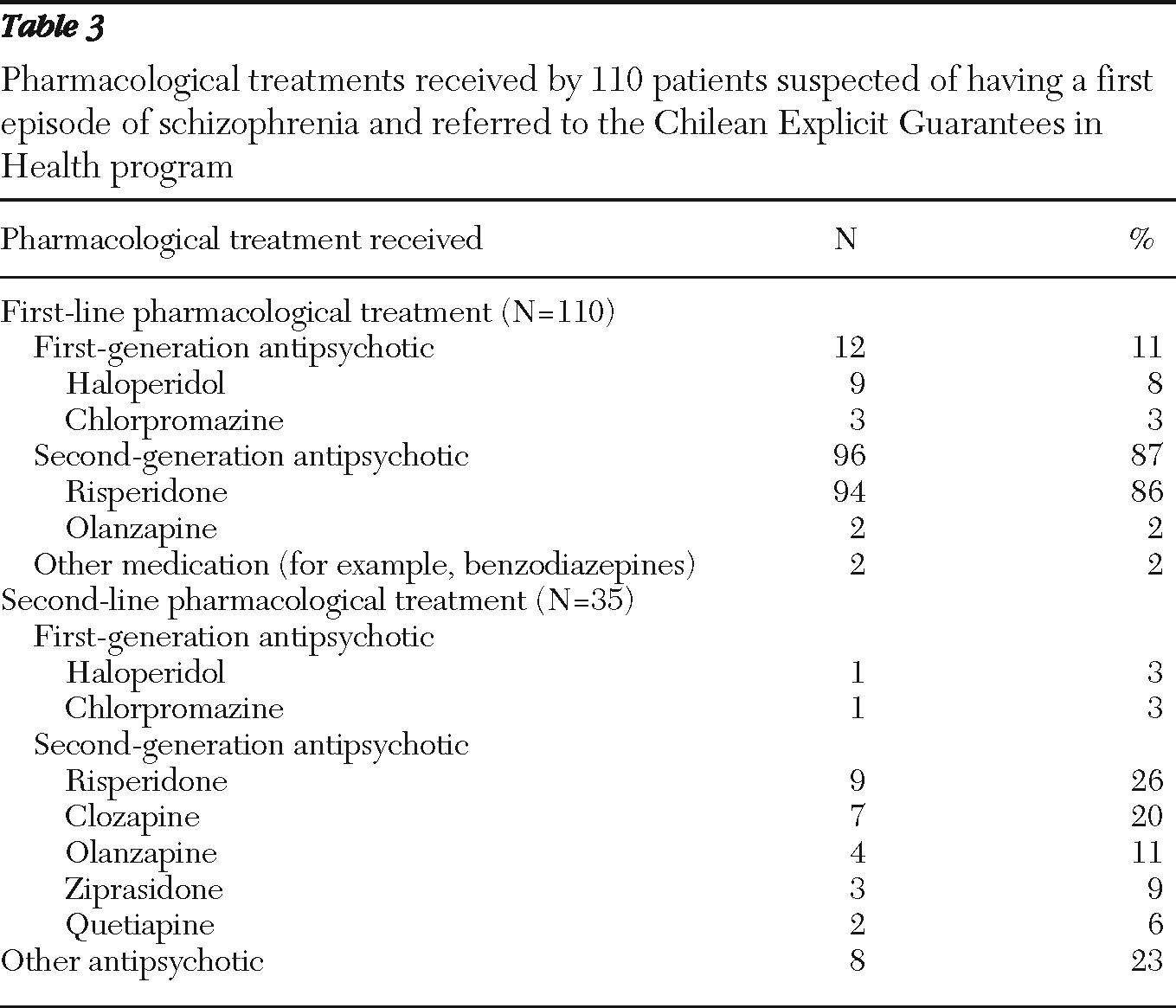

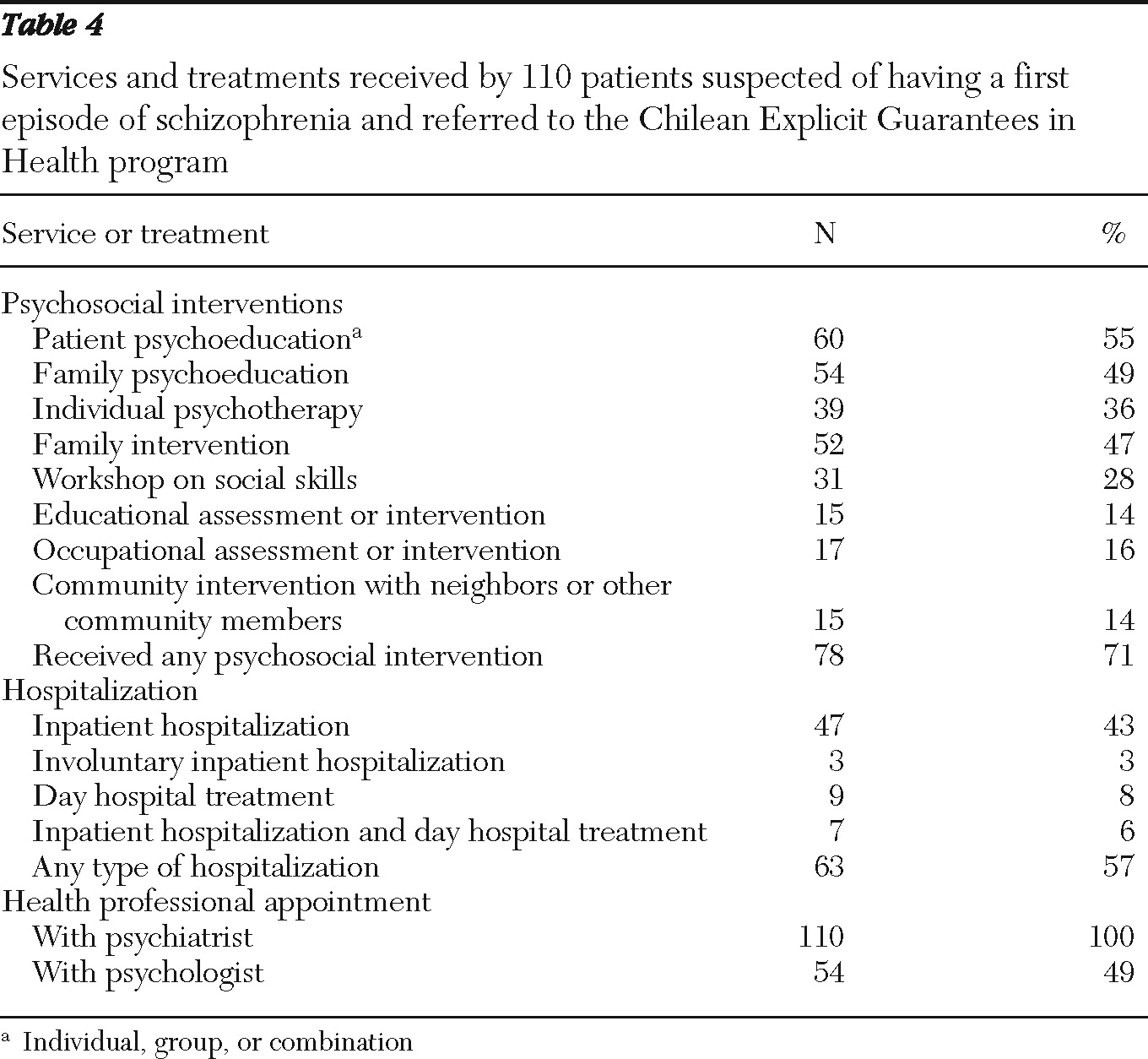

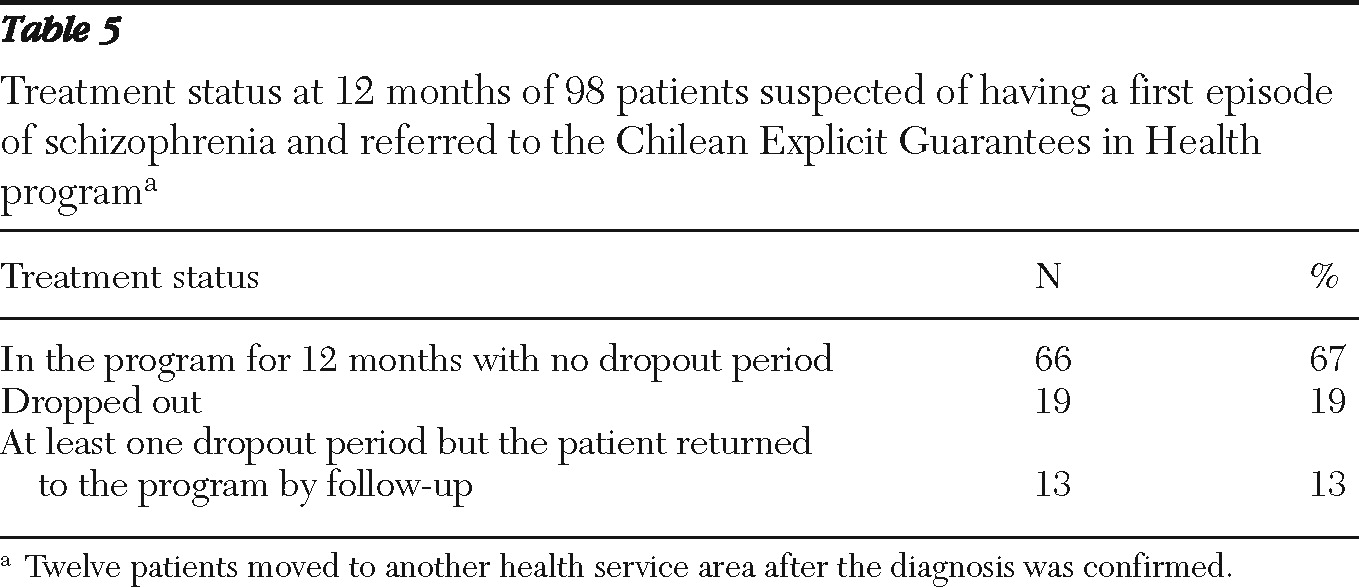

This study investigated adherence to clinical guidelines for first-episode schizophrenia in the pilot phase of the Chilean GES program by using a representative sample of 110 patients from various regions of the country. Adherence to guidelines on pharmacological treatment was remarkably good: 86% of patients received risperidone as a first-line treatment, as recommended by the guidelines. Adherence to recommended diagnostic measures, on the other hand, was low: even very basic laboratory tests were used for only 33%–70% of patients. Multiaxial ICD-10 diagnostics were used for 75% of the patients, but basic symptom scales (PANSS, CGI, and GAF) were used for only 20%–26%, even though use of the scales is recommended by the guideline. Fifty-five percent of patients received psychoeducation, and 71% received some type of psychosocial intervention. At the 12-month follow-up, 19% of patients had dropped out of treatment.

Adherence to guidelines

Not only is there no consensus on the definition of adherence to guidelines, a gold standard for adequate adherence is also lacking (

5). Many studies have found considerably lower rates of adherence than those in this study. In the Netherlands, for example, only 40% of patients with depression or anxiety disorders were treated according to clinical guideline (

14). In a review of adherence to mental health clinical guidelines, only 27% of nonintervention studies found adequate adherence rates (

5).

One reason for Chilean clinicians' remarkably good adherence to medication guidelines may be that this national program made second-generation antipsychotics widely available for the first time in public mental health services. Furthermore, psychiatric treatment in Chile is focused on pharmacologic therapies, and health professionals may have perceived this guideline recommendation as the most important. Clinicians did not record reasons for choosing another first-line treatment for some patients, but it is possible that risperidone had not yet arrived in all the clinics.

However, when moving to second-line antipsychotics, clozapine was used for 20% of patients even though the guidelines recommend it as the last alternative after a trial of four different antipsychotics. The rate of clozapine use may have been influenced by the fact that clozapine was the first second-generation antipsychotic introduced in Chile in the 1990s, and even though its use was restricted and required rigorous follow-up, clinicians were more accustomed to prescribing clozapine than other second-generation antipsychotics and were convinced of its effectiveness.

Other recommendations in the guidelines, including those on diagnostic procedures and psychosocial interventions, were not as rigorously followed. Lack of training in the use of symptom scales may partly explain their low utilization, but it is important to note that health professionals are not accustomed to using such scales or to evaluating outcomes in general and do not perceive the scales as important clinical tools.

About half of the sample received patient and family psychoeducation, but provision of other psychosocial interventions, particularly educational and occupational assessments, was low. It is possible that health professionals are not trained to conduct all the interventions recommended in the guideline.

Similar to our study, a study of U.S. patients with schizophrenia found that rates of adherence to recommendations for psychosocial treatment were much lower than for psychopharmacologic treatment, ranging from 0 to 43% (

28).

In Chile, laboratory tests are available without restrictions, but their low use may have been influenced by clinicians' lack of experience. Imaging studies, however, may not have been available for all patients, nor were they recommended by the guidelines for everyone.

Finally, it should be noted that this evaluation was carried out in the pilot phase just after the guidelines were launched, and it is possible that improvements have occurred since then.

Treatment dropout

Only 19% of patients had completely dropped out of the program at 12 months. This is an important achievement, and the rate is low compared with those in other countries. For example, in Italy and Spain, dropout rates ranging from 33% to 82% have been noted among patients in first-time psychiatric treatment (

29,

30). In Singapore, before the establishment of an early-psychosis program, the dropout rate was higher than 50% but fell to 19% for patients in the program (

31). Other studies have found rates ranging from 17% to 22% among patients with various mental disorders, including psychosis (

32,

33).

The Chilean program specifies measures to retrieve patients who drop out, such as home visits and telephone calls to patients who miss an appointment. Such measures were used for some patients in this study, which may explain why nearly half of the patients who dropped out returned to the program.