Years of well-controlled research trials have established that certain treatment techniques demonstrate better outcomes than others (

1). Yet little is known about whether such findings are reflected in the practices of therapists in community settings. Recent studies have suggested that empirically supported programs are not widely utilized, and outcomes are not as robust as those found in efficacy trials (

2–

5). Nevertheless, the rise in managed care has led to increased expectations that providers should apply evidence-based services and be held accountable for their clients' progress (

6–

11). This context naturally highlights the gap between the research literature and usual care, necessitating deeper understanding of routine clinical practice and effective elements of treatment.

Toward that end, a logical first step requires accurate and efficient measurement of treatment strategies. Whereas past research has examined treatment at the theoretical orientation level (for example, cognitive-behavioral) or the program level (for example, Coping Cat), new efforts have distilled manualized programs at the technique or practice element level (for example, exposure) (

12–

16). Measurement of these strategies falls into three broad categories: observational coding systems, client reports, and practitioner reports (

6). Although observational modalities provide objective information and are considered to be the gold standard of analyses (for example, Therapy Process Observational Coding System-Strategies Scale) (

16,

17), therapist reports are less time-consuming, require fewer resources, and are practical in day-to-day clinical contexts (

6). Thus far, several such instruments for practitioners have been developed, including the Therapy Procedures Checklist (TPC) (

18) and the Session Report Form (

19). The TPC represents practices from the most common therapeutic orientations (psychodynamic, cognitive, and behavioral, as identified by a sample of therapists). An exploratory factor analysis on techniques from the TPC supported a three-factor structure, and practice selection was determined by client characteristics such as age and problem area (

18,

20).

A similar therapist self-report measure was developed during a period of widespread system reform by the Hawai‘i Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division (CAMHD) (

21–

23). The Monthly Treatment and Progress Summary (MTPS) was designed to examine treatment targets, service format and setting, practice elements, and clinical progress ratings in an effort to make the local system of care more amenable to assessment (

24).

Practice elements on the MTPS were repeatedly revised based on the Distillation and Matching Model (

13). An initial list of 55 practice definitions was developed following a review of selected evidence-based treatment manuals and through discussions with local practitioners, intervention developers, and researchers (

23). In order to complete the Intervention Strategies portion of the MTPS, clinicians indicate yes or no on each of the practices (up to 55) that they provided in the previous month of service. Chorpita and colleagues (

13) reported good preliminary interrater reliability (

κ=.76) for 26 of the 55 items, and initial analyses of the practices suggested good one- and three-month test-retest stability (

κ=.65 and .50, respectively) (

25).

The study reported here had a dual purpose: to examine the factor structure of MTPS practice elements and to explore how this structure depicts therapist patterns in treatment as usual. Because the MTPS was rationally developed, an a priori organization was not assumed. However, because the TPC's factor structure is organized by theoretical orientation, with therapists using different techniques based on client characteristics (

20), we hypothesized that practice elements would arrange by theoretical orientation, client characteristics, or both. Specifically, younger clients with externalizing problems were predicted to receive more behavioral techniques, whereas older clients with internalizing problems were anticipated to receive more cognitive techniques.

Methods

Participants

Clinical data submitted between July 2002 and June 2008 were aggregated across every youth's first episode of intensive in-home services. Treatment episodes varied in length and could have included one or more months of therapy and multiple therapeutic sessions, as reflected by MTPSs. Thus, in this study, a treatment episode was defined as all services (for example, therapeutic sessions, care coordination) provided during a youth's first enrollment in coordinated intensive in-home treatment. To minimize statistical dependencies, we included data from only one randomly selected client in every lead therapist's caseload in the system (for which that therapist was the first therapist on the case) in the original sample of 285. Because clients with fewer than one corresponding MTPS per episode (minimum=1, maximum=39 MTPSs) were not incorporated into the analyses, seven therapists and their corresponding clients' clinical data were excluded, leaving a final sample of 278.

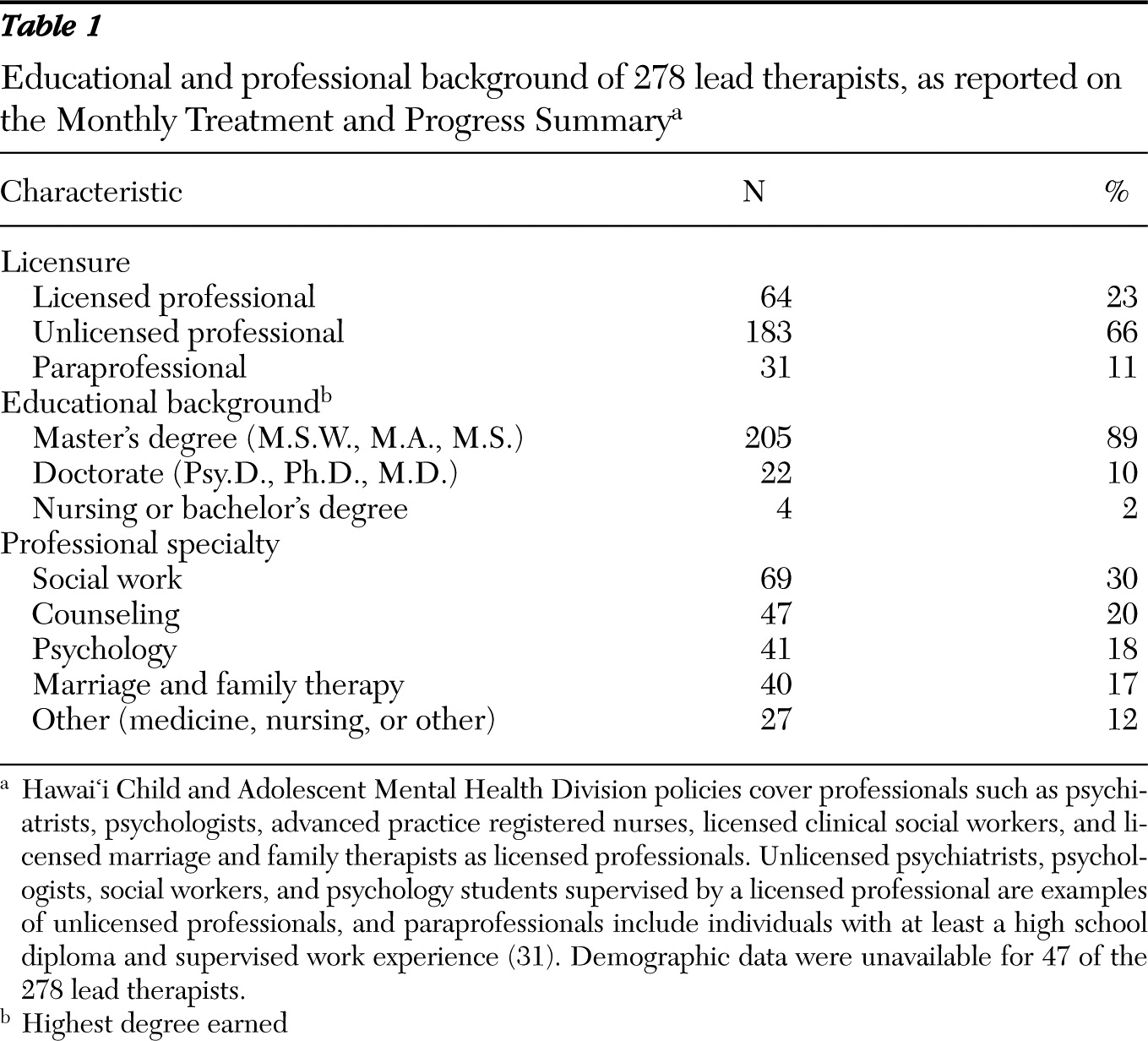

In the majority of cases, services were delivered by one therapist. However, 75 of the 278 treatment episode services were delivered by a team of therapists, with an average of 1.3 therapists per case. Treatment teams consisted of licensed professionals, unlicensed professionals, and paraprofessionals (

26). Solo or lead therapists had varying educational backgrounds and professional specialties. They were employed by one of eight agencies contracted by CAMHD to provide intensive in-home therapy, a nonmanualized, youth- and family-centered treatment designed to improve families' abilities to stabilize youths' functioning in their current environments (for example, home, school, and community) (

26).

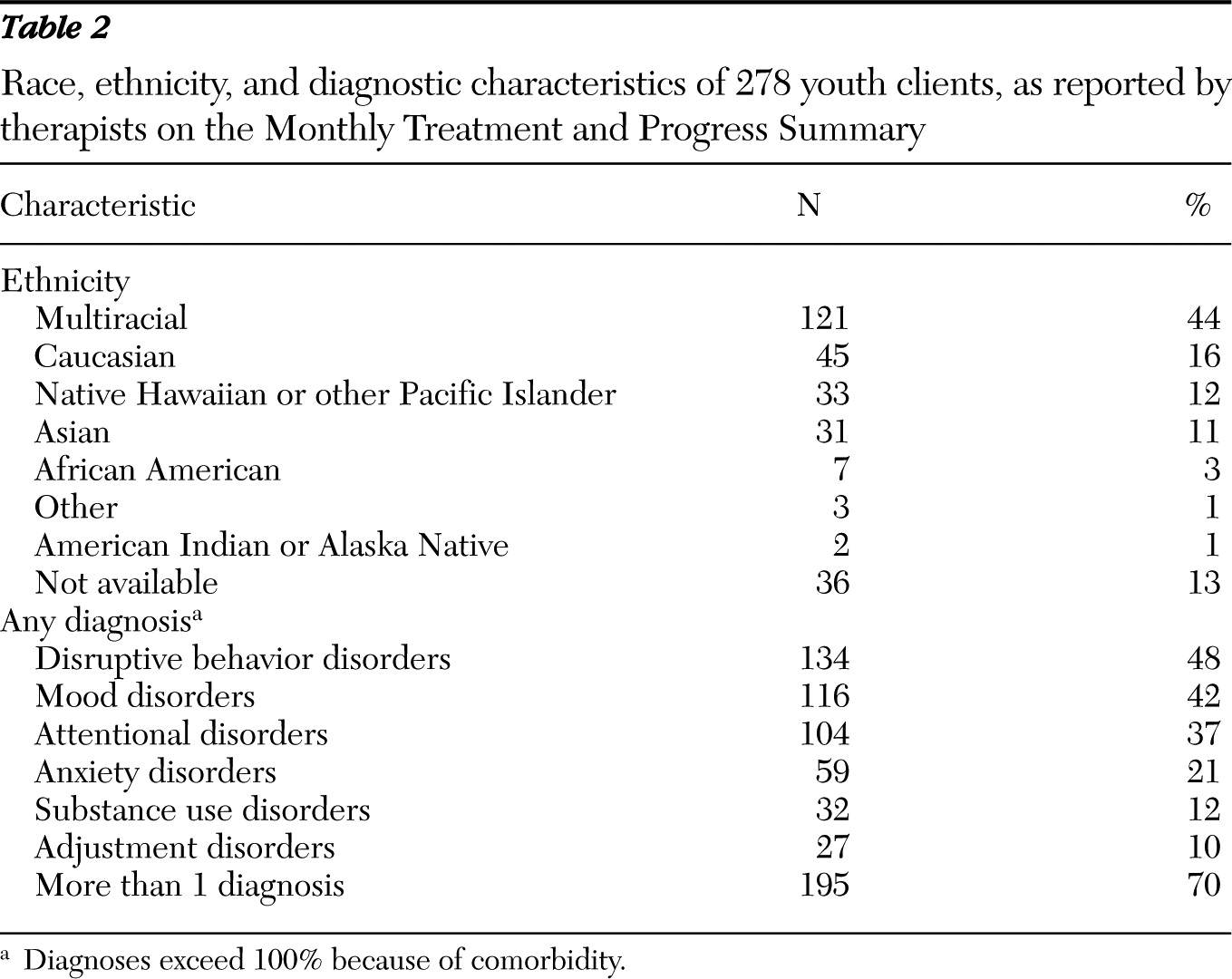

Selected clients reflected the general pattern of characteristics of youths receiving intensive in-home services from CAMHD in any given year (

27). They were racially and ethnically diverse, male (N=167, 60%), and had a mean±SD age of 13.5±3.4 years. Most participants had more than one diagnosis at the time of treatment entry.

Measurement

MTPS.

Twelve of the 55 practice elements listed in the MTPS were removed from analyses because of low use in the sample and unacceptably low interrater reliability, as identified by Chorpita and Daleiden (

12) (

κ<.65). Consequently, 43 practice elements were included in the initial factor analysis.

Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale.

The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS [28]) is a 200-item clinician measure that assesses youth functional impairment across eight domains. The youth is assigned a score on each subscale, based on the severity of his or her behaviors within the category. These scores are summed to create a total CAFAS score that can range from zero to 240, with higher scores indicating greater overall impairment. Care coordinators, certified for administration, served as the primary raters. The CAFAS has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, interrater reliability, stability across time, and concurrent validity and is sensitive to treatment change (

29–

32).

Procedure

Youth clients and their legal guardian or guardians provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of CAMHD's notice of privacy and disclosure procedures. Prior to treatment start, the CAFAS was administered in conjunction with a diagnostic assessment by a staff or contracted CAMHD clinician (for example, staff psychologist, psychiatrist, community psychologist) (

26). The University of Hawai‘i Institutional Review Board approved this study.

To create the most relevant list of intervention strategies, we examined practice element endorsements on all MTPSs across each youth's completed treatment episode. An exploratory factor analysis with an orthogonal varimax rotation and weighted least squares and mean variance-adjusted estimator was applied to the models in Mplus (Version 4.0 [33]). Mplus was selected because of its ability to accurately compute a solution with binary variables. After obtaining an initial solution, we used a promax oblique rotation (

34) to enhance the simple structure. This method is frequently used for exploratory factor analysis and is valuable because it can reflect the nuanced approach of therapists who blend elements from various theoretical orientations (

35).

Results

Characteristics of lead or solo therapists and their clients are presented in

Tables 1 and

2, respectively.

Factor analysis of practice elements

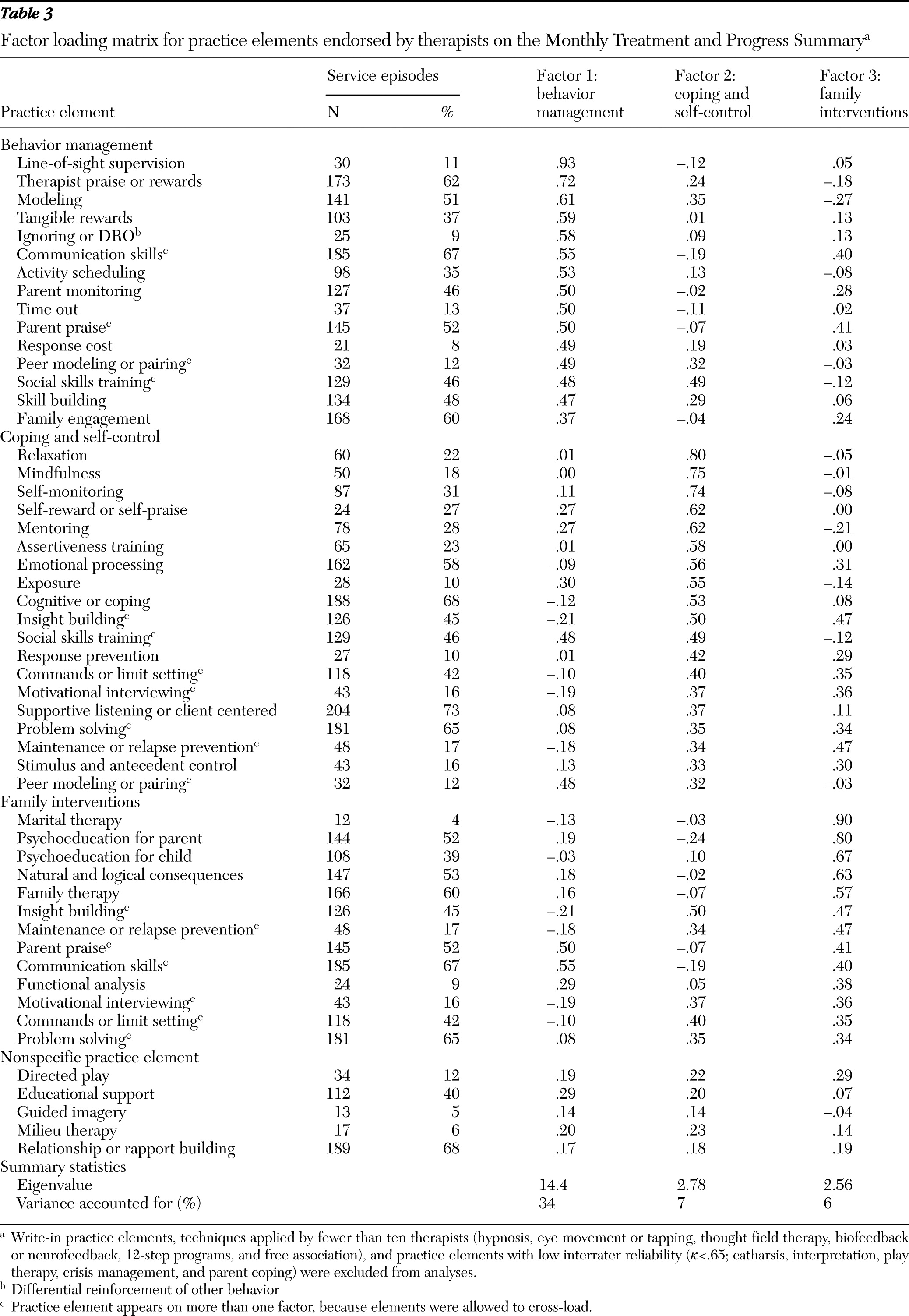

Frequencies of practice element endorsements across the sample are reported in

Table 3. Because we hypothesized that techniques would organize as a function of theory and client characteristics, we allowed practice elements to cross-load if they had loadings of at least .32 on both factors and differences of less than .2 between these loadings (

18,

36). Examination of the scree plot of eigenvalues (

37) revealed a break between the third and fourth factors, with the fourth factor not discernible from additional factors. The three-factor arrangement achieved a root mean square of approximation of .04, implying good fit. For these reasons, a three-factor model was selected, and minimum residual analyses were conducted and iterated. Practice elements were retained in the factor structure if they had loadings of at least .32 on any of the three factors (

36). As a result of these standards, five practice elements were not included in the final solution of 38. Finally, descriptive names were developed to reflect the content of each structure (

Table 3).

The behavior management factor represented 15 mostly behavioral intervention strategies implemented by therapists, caretakers, or other adults (for example, school teachers) to track and enhance compliance. The coping and self-control factor comprised 19 strategies aimed at helping youths help themselves. The family interventions factor consisted of 13 items predominantly focused on working with family members. Moderate positive intercorrelations between factors ranged from .46 to .52, and Cronbach's alpha was adequate to good (

38,

39) for the behavioral (

α=.81), cognitive (

α=.82), and family-oriented factors (

α=.78). The removal of any additional practices from the factor structure would not have led to improved alphas.

Sensitivity to therapist and client characteristics

The number of individuals providing treatment in a service episode, lead (solo) therapists' professional status and specialty, client age and diagnoses, and child functional impairment status at start of treatment were examined for relationships between these variables and lead therapists' reported use of practice elements on the factors derived from the exploratory factor analysis. Clinicians' factor scores were determined by summing the number of unique practice elements used one or more times during the treatment episode within each factor. This number was divided by the total number of practice elements on that factor to create a proportion score.

Treatment team characteristics.

Given that some cases involved treatment teams, we conducted analyses to examine differences on this dimension. When services were delivered by a team rather than by a single therapist, behavior management practice elements were more frequently used (mean±SD=.43±.24 and .35±.22, respectively; F=6.45, df=1 and 276, p=.01). Cases with at least one licensed professional providing treatment received more family intervention practices (.44±.25) than did those in which no licensed professional provided service (.38±.22; F=3.97, df=1 and 276, p=.05). In addition, if at least one unlicensed professional provided treatment, mean scores for behavior management were higher (.39±.22) than they were if no unlicensed professionals provided service (.31±.24; F=5.38, df=1 and 276, p=.02). Similarly, if at least one paraprofessional provided direct services, mean scores for behavior management tended to be higher (.44±.27) than they were if no paraprofessionals provided service (.36±.22; F=3.31, df=1 and 276, p=.07).

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) comparing factor scores as a function of the lead therapists' professional specialties (counseling, social work, psychology, marriage and family therapy, and other) revealed no significant differences between professional specialty groups. Because the sample population consisted primarily of master's-level therapists, we did not compare lead therapists' factor scores by educational background.

Client characteristics.

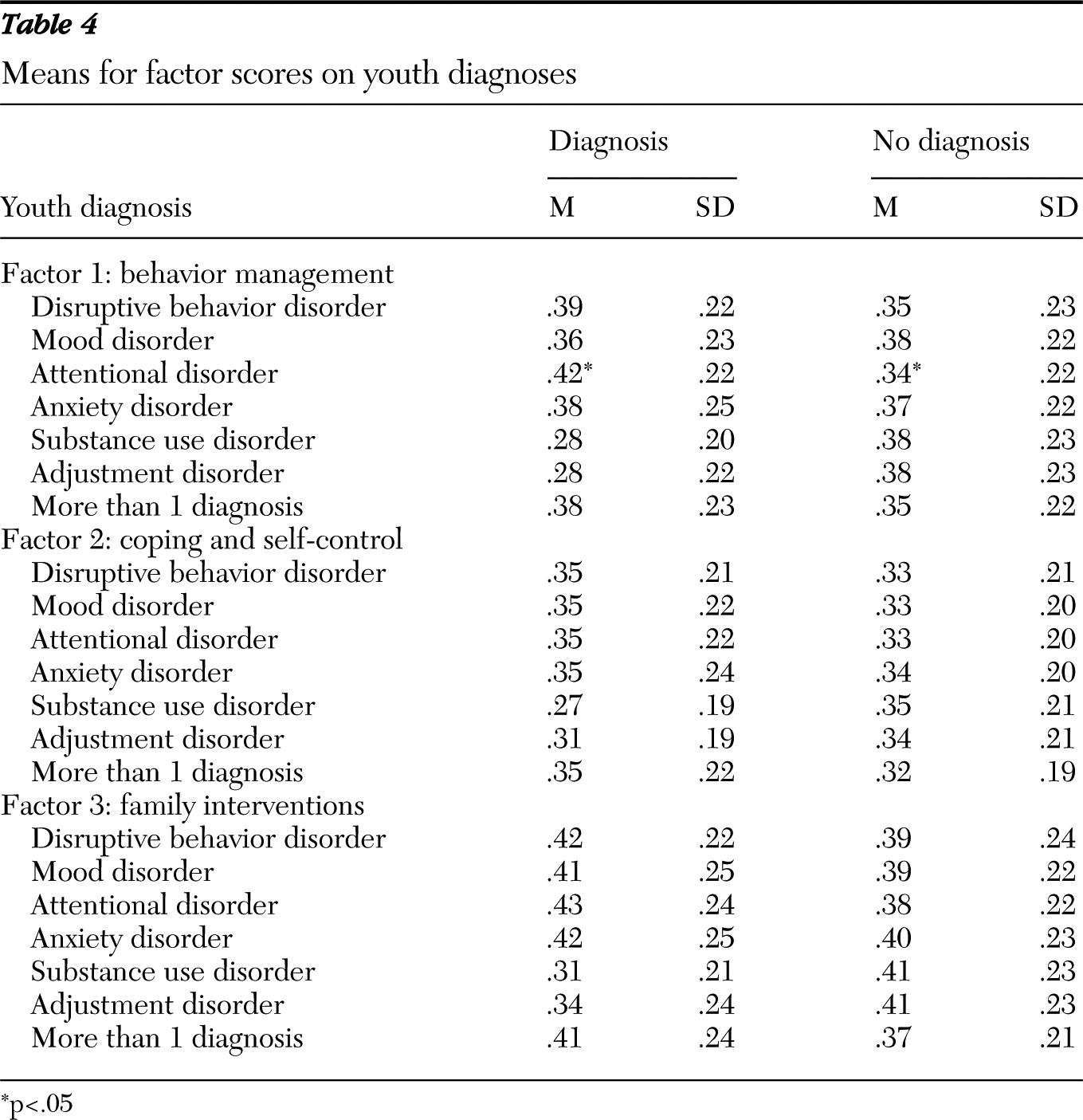

The use of behavior management practices was inversely correlated with client age (r=−.15, p<.05); however, age was not significantly related to either of the two other factors, coping and self-control or family interventions. A series of MANOVAs were conducted to examine whether factor scores were sensitive to diagnosis (that is, any diagnosis of adjustment, anxiety, attentional, disruptive behavior, mood, and substance use disorders;

Table 4). An overall effect was found for any attentional disorder, Hotelling's trace=.040, F=3.85, df=3 and 274, p=.01. Subsequent tests revealed significantly more use of behavior management practice elements for cases with any attentional disorder diagnosis (.42±.22) than for other cases (.34±.22; F=6.80, df=1 and 277, p=.01) and a nonsignificant trend for more use of family interventions.

Although no other diagnosis significantly predicted overall use of practice elements, two overall effects approached significance for substance use and adjustment disorders (Hotelling's trace=.025, F=2.32, df=3 and 274, and Hotelling's trace=.028, F=2.55, df=3 and 274, respectively). Subsequent tests indicated that youths with substance use disorders tended to receive fewer behavior management (.28±.20) and family intervention practices (.31±.21) than did youths without such diagnoses (.38±.23 and .41±.23, respectively; F=6.06, df=1 and 277, p=.014, and F=5.31, df=1 and 277, p=.022, respectively), and youths with an adjustment disorder received fewer behavior management practices (.28±.22) than did those without the disorder (.38±.23; F=5.01, df=1 and 277, p=.026). Use of coping and self-control practices did not significantly differ as a function of any diagnostic category.

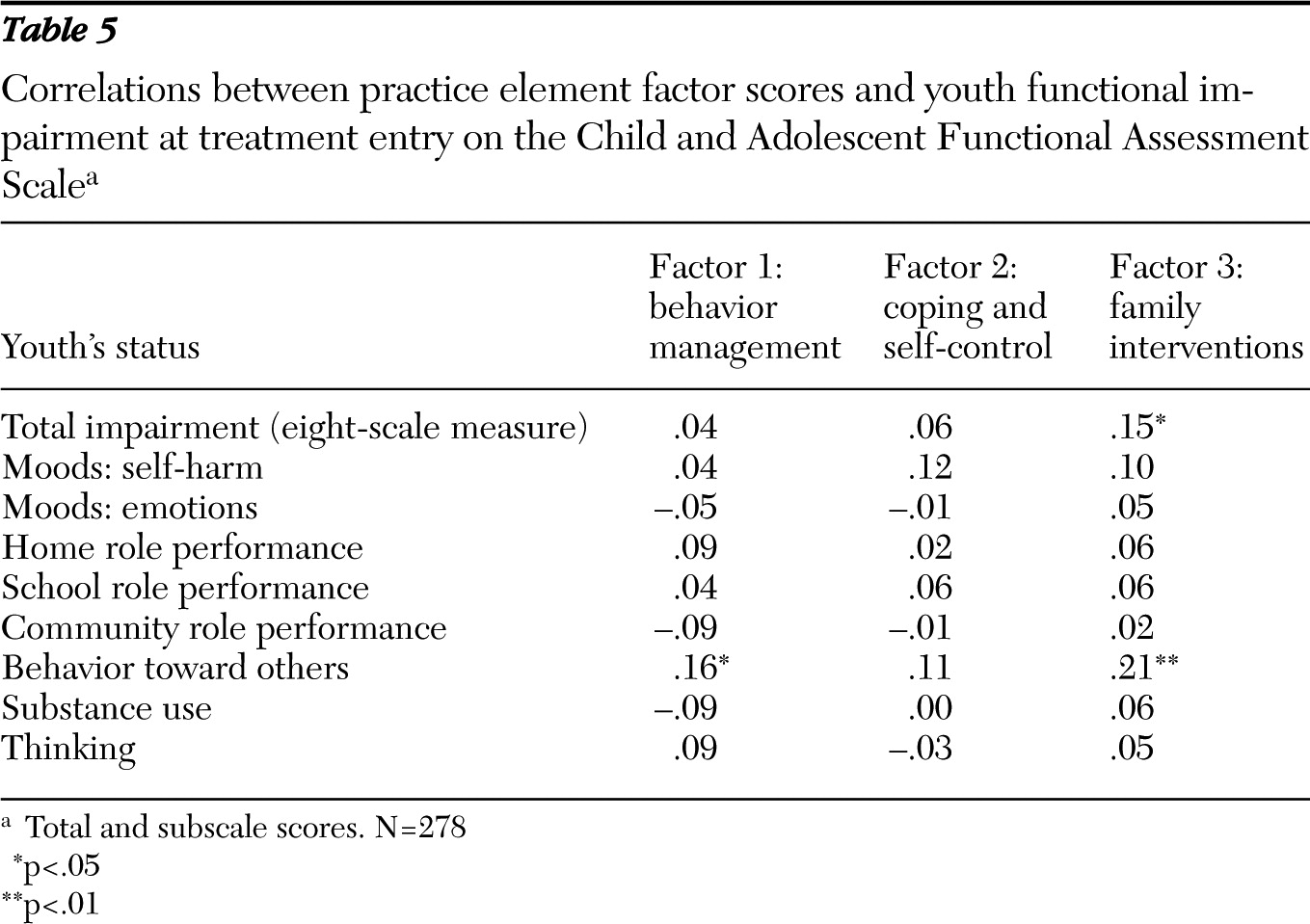

Higher levels of youth impairment (total CAFAS scores) were significantly associated with use of more family intervention practices (r=.15, p<.05) but not significantly related to use of behavior management or coping and self-control practices (

Table 5). Greater use of behavior management and family intervention practices (but not coping and self control) were associated with higher levels of impairment in behavior toward others (r=.16 and .21, respectively; both ps<.05).

Discussion

Psychometric findings

Exploratory factor analysis supported an interpretable three-factor structure (behavior management, coping and self control, and family intervention factors) of the MTPS, with some overlap in practices. Several items with contingency management and skills training components (for example, social skills training) cross-loaded on factors 1 and 2. However, most cognitive and self-control practices did not cross-load, indicating the selective use of behavioral or cognitive and self-help strategies for different cases or by different treatment teams. Much of this cross-loading between the second and third factors seems related to techniques that can be applied with youths, parents, or both. For instance, therapists can provide motivational interviewing to youths, parents, or both, and problem-solving is a common technique used to help with parent-child conflict in externalizing disorders (

40). Though the loading of techniques across factors seemingly complicates findings, such results point to nuances in an eclectic theoretical context (

41,

42). Also, similar outcomes can be expected from empirically versus conceptually derived scales (

43). Further research with the MTPS is needed to clarify whether dual loading reflects measurement problems (for example, misunderstanding of these items by the reporting therapist) or real phenomena.

Insights into usual care

Study findings also point to clues about usual care, in that client and therapist characteristics were related to patterns of selected techniques. Specifically, strategies on the behavior management factor were used more frequently with younger clients, those with attention disorders, and those with greater functional impairment regarding behavior toward others. In addition, treatment teams were more likely to apply family intervention techniques with youths with greater overall impairment. Therapists' professional status was also related to practice element application, given that treatment teams with licensed professionals tended to use family intervention practices more than did teams without licensed providers. Interestingly, teams with at least one unlicensed provider, paraprofessional provider, or both tended to employ more behavior management practices than did teams without unlicensed or paraprofessional providers. This converges with the child psychotherapy outcome literature, which has suggested that professionals tend to produce larger effects than paraprofessionals in treating problems such as anxiety and depression, whereas paraprofessionals using behavioral methods tend to have larger outcomes than professionals (

44). Consistent with findings from Walker and colleagues (

20), we found that other lead therapist characteristics (for example, terminal degree) did not predict the use of practice elements from the factor scores.

Limitations

Although these results and their adequate congruence with other research on treatment as usual are promising, several methodological shortcomings should be considered. Given the exploratory nature of this study, we did not control cumulative alpha in the analysis of factor predictors. Thus confirmatory factor analyses should be conducted in order to validate the factor structure. Next, decisions to exclude low frequency and reliability practices were statistically indicated, but they limited the ability to examine how such items might contribute to the factor organization. Unlike Weersing and colleagues (

18), who reported that factors aligned with theoretical orientations, we did not find a psychodynamic factor. Although such a finding may have emerged if deleted items had been included, low-frequency items suggest that such techniques were not frequently endorsed by therapists in this sample.

Although the use of self-report is a simple and cost-effective method of studying treatment as usual, it may be less effective than observational coding at identifying subtleties in treatment delivery. This is particularly relevant, given that Garland and colleagues (

45) have indicated that nuanced variables such as technique intensity are pertinent to studies of usual care. Furthermore, research has pointed to inconsistencies between direct observations of therapist behaviors and their self-reports (

46,

47). Studies on the validity of instruments (for example, MTPS) are thus needed to both understand and control for these discrepancies.

The inclusion of information from a single randomly selected client per practitioner provided statistical advantages but begged the question about the extent to which therapists used different strategies with different clients. Because other researchers have found that client characteristics predicted practice use (

18), it is possible that therapists and therapy teams may have systematically varied practice use within their caseloads. That said, much more research is needed in this particular area. Finally, this study was conducted with a sample of youths receiving intensive in-home services in a system of care that had undergone considerable recent reform. The practices that therapists used in other levels of care (for example, out-of-home services) and in other systems of care is an open question.

Conclusions

The MTPS shows potential as a therapist report of practices and offers many advantages to further the science and practice of youth mental health. Because the initial set of practice elements was derived from research-validated protocols and because multiple research reviews have utilized this metric (

12,

25,

48), techniques reported by clinicians in Hawai‘i can be monitored on an ongoing basis and compared with the literature at individual (

10) and aggregate levels (

11). Practically, when evidence-based practices fail during transportation to community settings (

7,

49,

50) or when effects are less than those found by developers (

51), the MTPS may facilitate a better understanding of actual therapist practices. Specifically, clarity regarding successes and failures of treatment implementation can be gained through comparisons of a client's MTPS to an MTPS profile selected to reflect the evidence-based program. The MTPS can also be used to examine the impact of specific practice elements on youth outcomes beyond the context of manualized programs, which would help test the hypothesis that the application of practices derived from the evidence base predicts greater rates of improvement in usual care (

52). Study results also point to innovative opportunities, such as simplifying treatment assessment procedures (for example, organizing practices along factor dimension) and targeting training on the basis of these factors, therapist and client characteristics, or a combination. Effective measures of practice can improve services for youths and families through enhanced monitoring, feedback, and individual reflection.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by the Research and Evaluation Training project funded by the State of Hawai‘i's Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, and of which Dr. Mueller is the primary investigator. Dr. Daleiden benefits from consulting related to evidence-based services and worked as a consultant to the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health during this project. He is currently the chief operating officer of PracticeWise, LLC. The other authors report no competing interests.