The transition from adolescence to adulthood is especially challenging for youths with mental illness (

1). Compared with their peers without mental illness, transition-age youths (generally, youths ages 16–25) with mental illness have lower rates of education and employment and higher rates of poverty, unplanned pregnancy, substance use disorders, homelessness, and criminal justice involvement (

2–

4). The challenges inherent in the transition to adulthood among these youths are often more difficult because of emancipation from foster care, a lack of mentors, and mental health service needs related to life transitions that are not adequately met by the mental health system (

5–

7).

The bifurcation of the child and adult mental health systems presents several challenges for transition-age youths. When youths reach adulthood (typically defined as age 18 or 21), they often lose their eligibility for Medicaid, which funds a large portion of public mental health care (

8,

9). Many adult service providers do not focus on the development of independent-living skills, which is a commonly cited service need among transition-age youths living with mental illness (

10). Consequently, transition-age youths are more likely to drop out of mental health treatment, and older youths who use mental health services are more likely to be referred from the criminal justice system (

11–

13). Predictors of dropout among youths include practical barriers to accessing care, the perceived relevance of treatment, and the quality of the therapeutic relationship (

14–

16). Concerns about the adult mental health system's ability to engage and retain youths in treatment have prompted calls for services that are targeted to transitional years (

8,

17).

On November 2, 2004, California voters approved Proposition 63, which was signed into law as the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA). Transition-age youths were designated as a priority population under the MHSA. New services provided through this initiative have included youth-specific outpatient programs. This study examined changes in service use associated with providing age-specific services for transition-age youths in San Diego County, California.

Methods

Standard adult outpatient programs

The standard adult outpatient programs in San Diego County provide mental health services to adults with mental illness, including persons with co-occurring substance use disorders and those who are uninsured or who are insured by Medicaid. Most clients (74%) are adults ages 25–59. These programs are based on a psychiatric rehabilitation model and provide services that focus on competency, recovery, and empowerment, and they incorporate social, educational, occupational, behavioral, and cognitive interventions aimed atlong-term recovery and maximization of self-sufficiency. These services are intended to provide physical, emotional, and intellectual skills needed by persons with mental illness to live, learn, and work in their particular environments (

18). Program staff use evidence-based practices such as integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment as well as illness management and recovery. Several member-run clubhouses provide educational and vocational supports as well as socialization and wellness activities; some of these clubhouses follow the International Center for Clubhouse Development clubhouse model, whereas others use a more generic model. Clients are typically referred to an outpatient program after calling a mental health access and crisis line.

Outpatient programs specifically for transition-age youths

Outpatient programs for transition-age youths in San Diego County follow the psychiatric rehabilitation model described above for adults, but they are tailored for youths ages 18–24. These youth-specific programs employ staff with experience in providing services to youths. The programs collaborate with agencies within the children's system of care and the child welfare system to assist with clients' eventual transition into the adult system of care. Youth-specific programs focus on independent-living skills and age-appropriate social skills. For example, youth-specific programs provide therapeutic groups on the topics of relationships and dating, family supports, and housing and living with roommates. Educational and vocational services may include a staff person who accompanies a youth to a community college or potential job site. Youth-specific clubhouses provide a place for youths to gather and socialize. Youths with mental illness who have been trained as peer specialists provide mobile outreach to youths and meet them where they can be most comfortable to effectively begin treatment engagement. Youths may be referred to a program either by the access and crisis line or by an adult outpatient program.

Analysis methods

Study sample.

Data from the San Diego County Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services management information system (MIS) were used to identify transition-age youths who first initiated services with a youth-specific outpatient program or with an adult outpatient program between October 1, 2006 (when the youth-specific programs were implemented), and July 1, 2009. In our analysis, youths who first initiated treatment at an adult outpatient program but who later sought services at a youth-specific outpatient program were considered to have initiated treatment at the youth-specific outpatient program. Youths who initiated treatment at an adult outpatient program within one year prior to October 1, 2006, and who did not later initiate treatment at a youth-specific program were excluded from the study sample.

The MIS combines an electronic health record (including assessment and treatment planning) with an encounter-based utilization management and billing system. Thus the MIS provides information on clients' demographic and clinical characteristics as well as a comprehensive view of services received. Client demographic and diagnostic information was gathered from the assessment data and included age, gender, race and ethnicity, clinical diagnosis, and Medicaid coverage. We limited the sample to youths ages 18–24 because few youths ages 16 or 17 received services in the youth-specific or adult programs.

Mental health service utilization.

Information on service utilization was derived from the MIS. We calculated outpatient visits, inpatient and emergency room admissions, and days receiving mental health services in the jail over one year before (preperiod) and up to one year after initiation of treatment (postperiod) at an outpatient program. Outpatient visits were calculated as the number of unique days that clients received outpatient services. Outpatient services included assessments; case management; crisis intervention; medication management; individual, family, and group psychotherapy; and other psychiatric rehabilitation services. Outpatient services were provided by outpatient programs, stand-alone case management programs, or fee-for-service providers (independent psychiatrists and psychologists). We did not include day or partial-day treatment programs or substance abuse treatment services that were provided by Alcohol and Drug Services.

Inpatient admissions included admissions to the county psychiatric hospital or to psychiatric floors of acute care hospitals. Emergency services included admissions to the county emergency psychiatric unit and use of the psychiatric emergency response team.

Utilization data were available from July 1, 2005, through December 31, 2009. Thus clients had a full year of exposure to services in the preperiod and a minimum of six months exposure in the postperiod.

Propensity scoring.

We used the Becker and Ichino (

19) algorithm, implemented in Stata 10, to estimate a propensity score predicting participation in a youth-specific outpatient program (versus an adult outpatient program) and to determine whether the propensity score was balanced on observable characteristics. In a logistic regression model the propensity score predicted participation on the basis of demographic and clinical characteristics described above. We tested for and found no significant interactions between the predictor variables. We further assessed goodness of fit using a modified Hosmer-Lemeshow test and a Pregibon's link test (

20,

21). The Becker and Ichino algorithm determined that resulting propensity scores were balanced on observable characteristics. We have also used this approach to identify comparison groups for analyses of San Diego County's supported housing programs (

22,

23).

The University of California, San Diego, Institutional Review Board and the San Diego County Mental Health Services Research Committee approved the use of these data for the purpose of this study in accordance with the Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Study design and statistical analysis.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between the two groups with chi square tests. Mental health service use was analyzed both pre-post services, and pre-post services with a contemporaneous control group using a quasi-experimental, difference-in-difference (DID)design (

24). We estimated both a standard DID model and a DID model with inverse propensity score weighting to ensure the balance of covariates across the comparison groups.

We analyzed mental health services by using four two-part models. The two-part model is commonly used to estimate health care costs when the dependent variable is nonnegative and when its distribution is noticeably skewed and kurtotic (with a heavy right-hand tail) (

25). Logistic regression was used to estimate the probability of any use of a service, and negative binomial regression was used to estimate the number of services conditional on receiving at least one service (

26–

28). We assessed goodness of fit using a modified Hosmer-Lemeshow test and a Pregibon's link test (

20,

21).

In all models, age, gender, race-ethnicity, clinical diagnosis, and indicators for comorbid substance use disorder and Medicaid coverage were included as additional covariates. In the pre-post model, an indicator variable identified the postperiod. In the DID models, indicator variables identified the program, the postperiod, and the interaction between the program and the postperiod. We adjusted for exposure in the postperiod by including an exposure offset in the second part of the model (

29).

Incremental effects associated with each program were standardized to the underlying population characteristics; these effects were calculated over both parts of the model and were adjusted to a full year of exposure. We computed several sets of estimates from these regressions: pre, post, and difference estimates for each program; a DID estimate comparing youth-specific with adult outpatient programs; and a propensity score-weighted DID estimate. In each of the DID models, the control group difference removed the time trend. Standard errors were calculated with the nonparametric bootstrap, and p values were computed with the percentile method from the empirical distributions of the results from 1,000 replications (

30).

Results

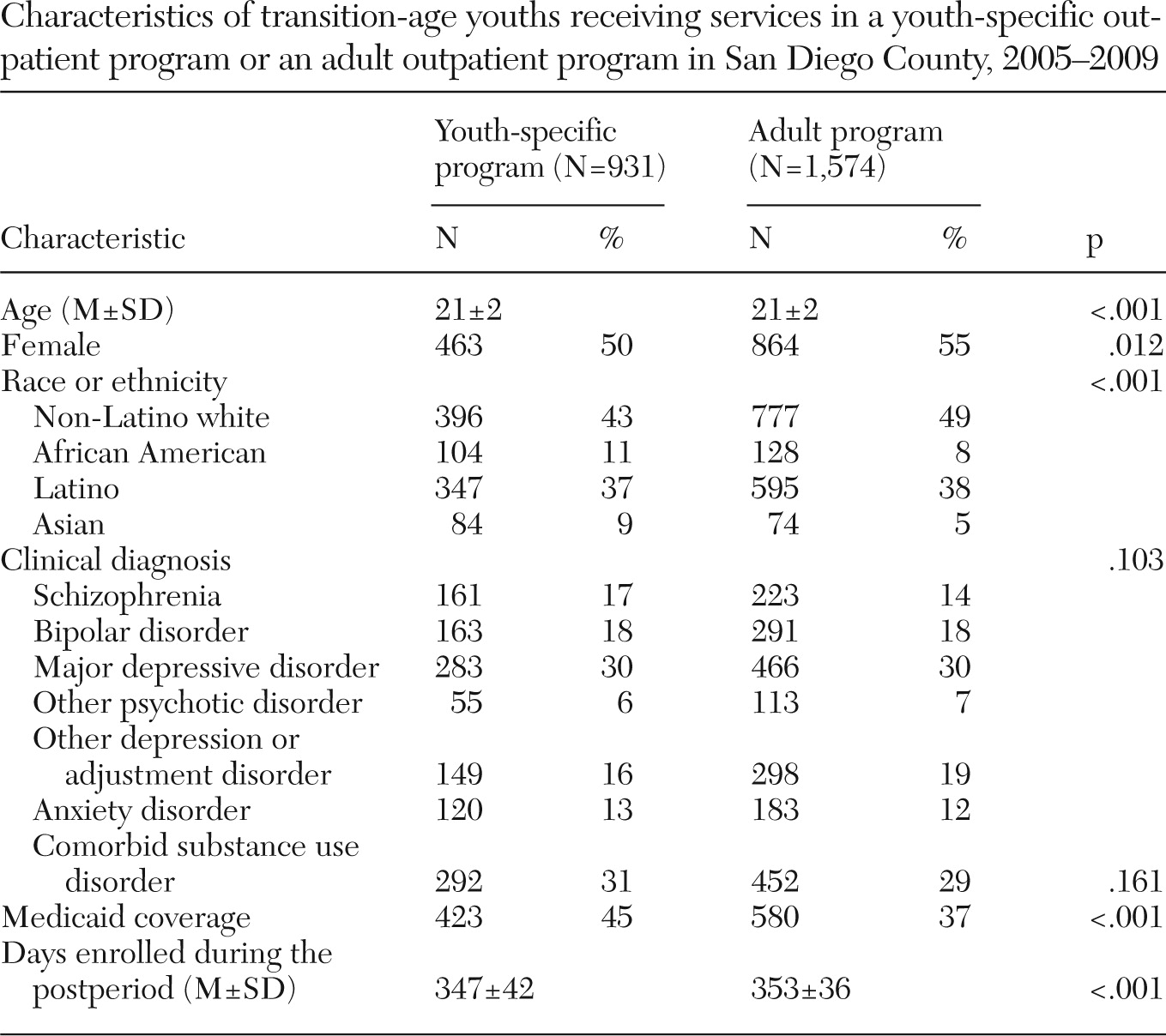

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics of 2,505 transition-age youths participating in a youth-specific outpatient program (N=931) or an adult outpatient program (N=1,574). Compared with youths in adult programs, clients in youth-specific outpatient programs were less likely to be female (p=.012) and more likely to be African American (p=.011) or Asian (p<.001) and to have Medicaid coverage (p<.001). There were no statistically significant differences in diagnosis or comorbid substance use disorder between the two groups.

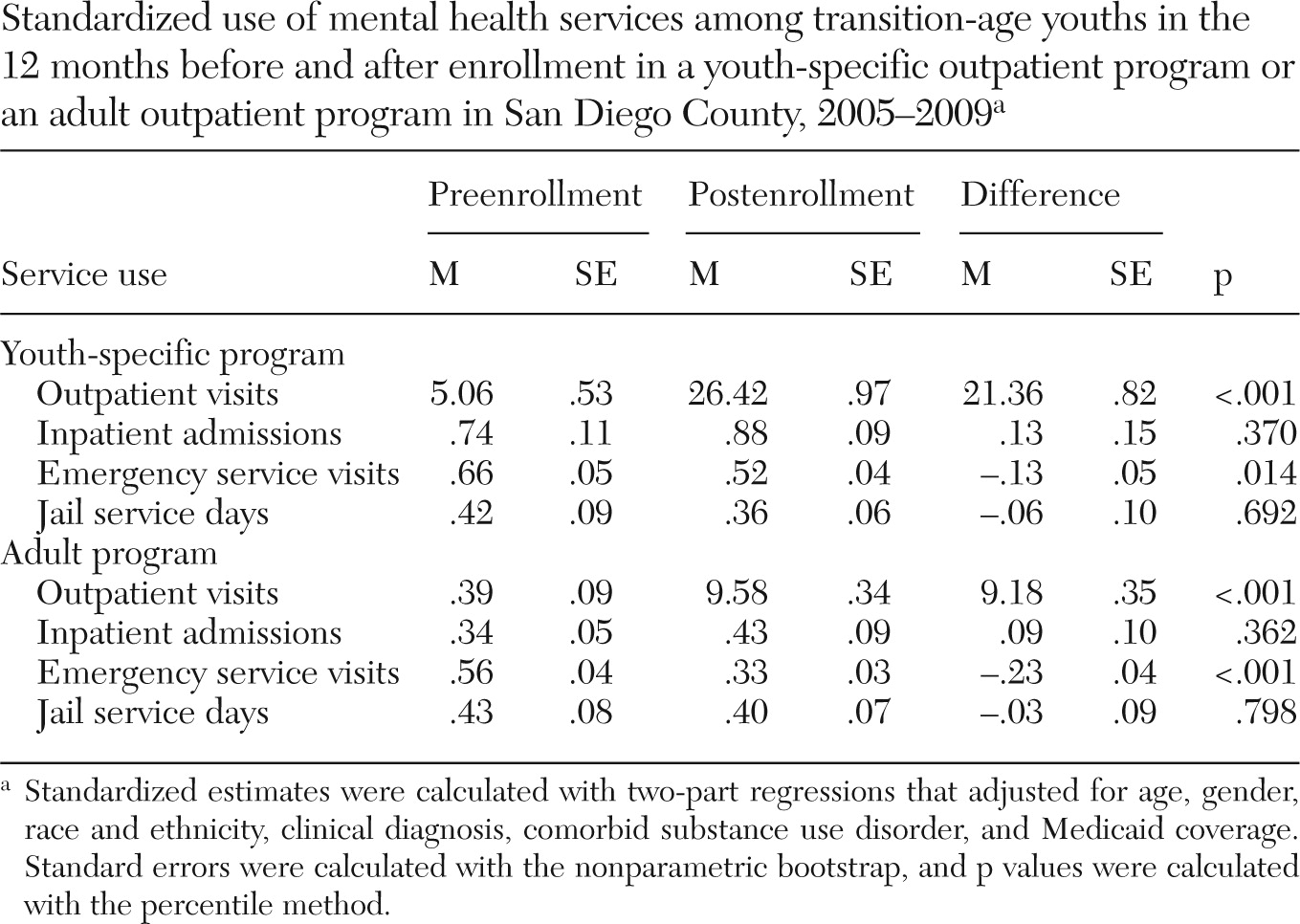

Table 2 shows the standardized use of mental health services among transition-age youths in the 12 months preenrollment and 12 months postenrollment in a youth-specific or adult outpatient program and the difference in one-year standardized use. Outpatient visits increased by 21.4 and 9.2 visits among youths initiating service in a youth-specific outpatient program and an adult outpatient program, respectively (p<.001 each). Twenty-nine percent of youths initiating services at a youth-specific outpatient program received services from an adult outpatient program in the preperiod. Emergency admissions declined by .1 among clients in a youth-specific outpatient program (p=.014) and by .2 among youths in an adult outpatient program (p<.001). There were no statistically significant differences in inpatient admissions or jail service days.

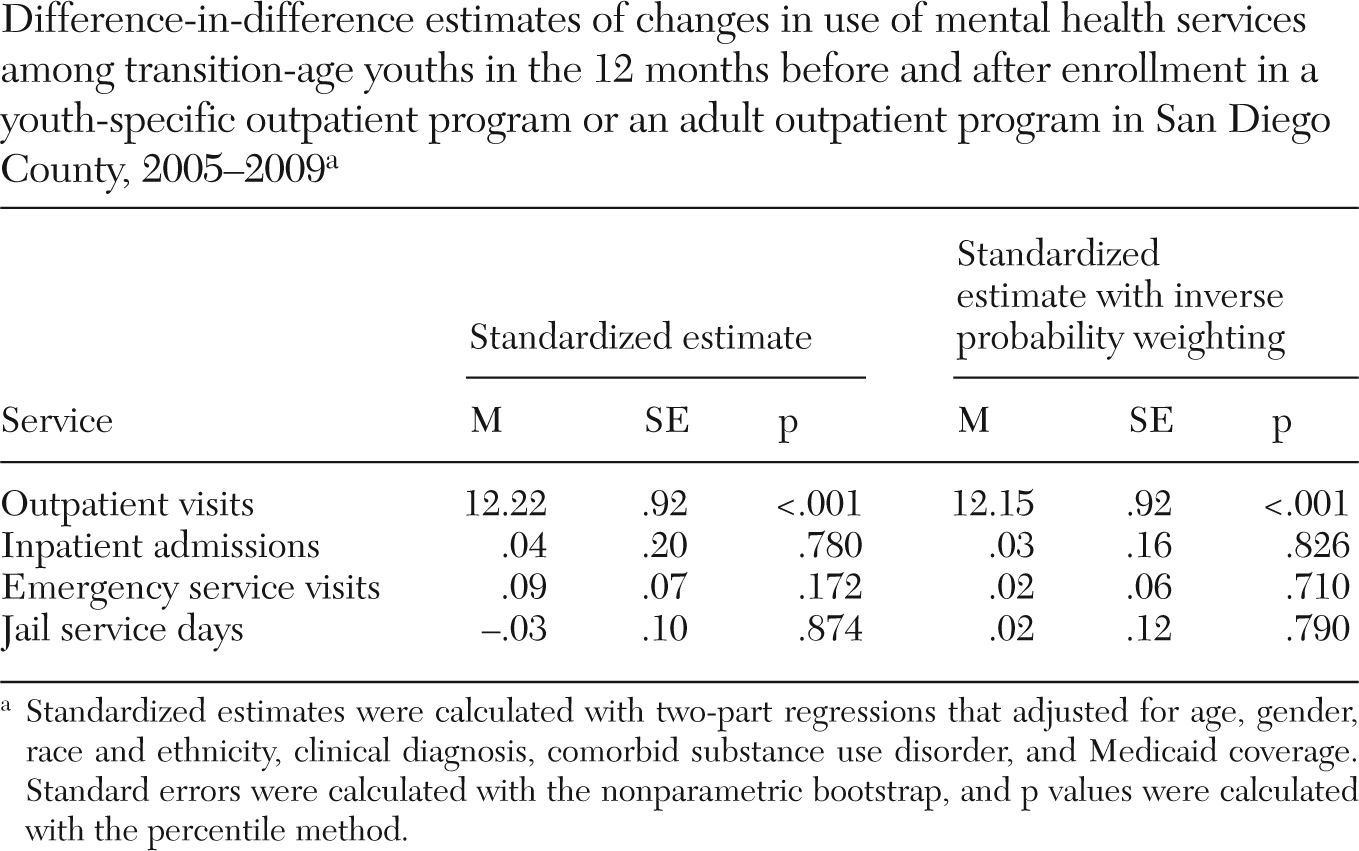

Both standard and propensity score-weighted DID estimates of standardized mental health services use are shown in

Table 3. The two sets of estimates are very similar; we focus here on the DID estimates with inverse probability weighting. Compared with youths in adult outpatient programs, clients in youth-specific outpatient programs had 12.2 more outpatient visits (p<.001). There were no statistically significant differences in inpatient admissions, use of emergency services, or jail service days.

Discussion

In this study, we examined changes in mental health service utilization among youths receiving age-specific services in San Diego County. We found that clients in youth-specific outpatient programs had a significant increase in use of outpatient mental health services compared with clients in adult outpatient programs. In 12 months before the initiation of treatment at an age-specific program, youths averaged fewer than six visits to outpatient mental health providers. However, after initiating treatment in youth-specific services, youths averaged more than 20 outpatient sessions.

This study is subject to limitations in design, potential selection bias, use of administrative data, and generalizability. Our study was not designed to measure the effectiveness of the age-specific programs in improving outcomes among youths. Previous studies found that although children and youths received a higher number of services in redesigned systems of care, there were no improvements in clinical or functional outcomes relative to children and youths receiving services in more traditional settings (

31,

32). However, these studies included both children and youths and examined redesign strategies in a children's system of care. The programs studied here focused on remedying well-documented deficiencies in services provided to transition-age youths within an age-specific system of care.

Although we accounted for differences in observable differences through the use of multivariate analysis and inverse propensity score weighting, there may remain unobservable differences between the groups that biased our estimates of the programs' effects. The administrative data used did not have client-specific information on the use of evidence-based therapies, specific care process, attrition, or clinical outcomes. This was a study of a single county, and therefore our results may not be generalizable to other counties in California or other states that have implemented age-specific programs.

Conclusions

This study suggests that compared with traditional adult outpatient mental health programs, age-specific programs are associated with increases in outpatient service use. Future research is needed to assess the effectiveness of age-specific programs for transition-age youths and how use of these programs relates to improved clinical, educational, and vocational outcomes over time.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study received financial support from the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services. Dr. Ojeda is supported by grant K01-DA025504 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors gratefully acknowledge the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services for access to the management information systems and the UCSD Health Services Research Center for research support.

The authors report no competing interests.