Recruiting for a randomized clinical trial comparing psychotherapies for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), we noticed that many prospective enrollees reported or expressed psychotic symptoms. This observation, contradicting the literature and our lengthy clinical experience, challenged assumptions about what individuals with psychotic symptoms consider acceptable or even desirable treatment. Unaware of studies reporting similar experiences, we explored characteristics of these individuals and of our study design that might have prompted those who often avoid mental health care to seek participation in our research treatment program. We extracted available chart information to see how these individuals differed from those who were eligible for the study. We hoped to garner insights that might improve treatment engagement of patients with psychotic symptoms.

Methods

This exploratory study was part of a larger study on psychotherapy for PTSD. The parent study was advertised in local papers, on Web sites, by flyers on university and hospital bulletin boards, and by word of mouth within the clinic. The intake procedure started when applicants telephoned nonclinician research assistants, who conducted a brief, semistructured phone screen. Individuals who reported a trauma and appeared eligible were scheduled for a clinical interview with an experienced research psychiatrist. After applicants signed consent forms previously approved by an institutional review board for intake, the psychiatrist interviewed individuals to determine, through clinical impression, whether they had experienced a

DSM-IV-defined trauma, whether PTSD was their primary axis I diagnosis, and whether they were eligible for the study. A reliable independent evaluator who was a doctoral-level psychologist interviewed the eligible applicants, using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (

1) and Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV (SCID-I and SCID-II [

2,

3]) to establish current and lifetime diagnoses. Exclusion criteria included psychotic disorders; bipolar disorder; unstable medical condition; active substance dependence; active suicidal ideation; and antisocial, schizotypal, or schizoid personality disorder. Ineligible study applicants were offered clinical referrals.

A literature review revealed no comparable studies. We conducted a structured retrospective chart review of all research applicants who completed the initial evaluation, focusing on the subset of 38 applicants who were excluded from eligibility because of psychotic symptoms. We extracted, where available, demographic data, trauma type, number of reported traumas, type of psychotic symptoms, history of mental health treatment and psychotropic medications, and presence of PTSD. For individuals evaluated by the independent evaluator, we included CAPS severity.

Statistical analyses using SPSS software included t tests for continuous data and chi square tests for categorical data. This investigation being exploratory, no correction was made for multiple statistical comparisons.

Results

Of 223 study applicants screened by an intake psychiatrist, 38 (17%) were found to have psychotic symptoms. Psychotic symptoms were detected in the initial interview of 31 applicants, who were excluded from further evaluation for the parent study. An additional seven individuals were later identified by SCID assessment, six of whom also completed the CAPS. Of these 38, only 26 were assessed for comorbidity, either by clinical psychiatric impression or SCID. The remaining 12 revealed psychotic symptoms early in the interview, curtailing further evaluation. Of the 26 assessed for comorbidity, 73% (N=19) were thought to have PTSD. Of the six individuals administered the CAPS, five (83%) met the severity cutoff score (CAPS score >50) for study entry and 100% met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. [A flowchart summarizing the selection process is available online as a data supplement to this report.]

Of the 38 individuals with psychotic symptoms, 24 (63%) were male and 14 (37%) female. Seventeen (45%) described themselves as white, 11 (29%) black, five (13%) Asian, two (5%) white Hispanic, two (5%) nonwhite Hispanic; one described racial-ethnic background as unknown. Psychotic symptoms included paranoia (N=28 of 34, 82%), delusions (N=19 of 33, 58%), auditory hallucinations (N=13 of 33, 39%), ideas of reference (N=5 of 33, 15%), visual hallucinations (N=4 of 33, 12%), and thought disorder (N=3 of 33, 9%), with a mean±SD of 2.18±.68 symptoms per person. Five charts lacked sufficient information to specify psychotic symptoms. Thirty-six (95%) reported an objective trauma that met PTSD criterion A, and 32 (84%) reported multiple traumatic events. At least 79% (N=30) reported previous mental health treatment. The most frequently reported childhood traumas were physical abuse (N=19, 50%) and emotional abuse or neglect (N=13, 34%).

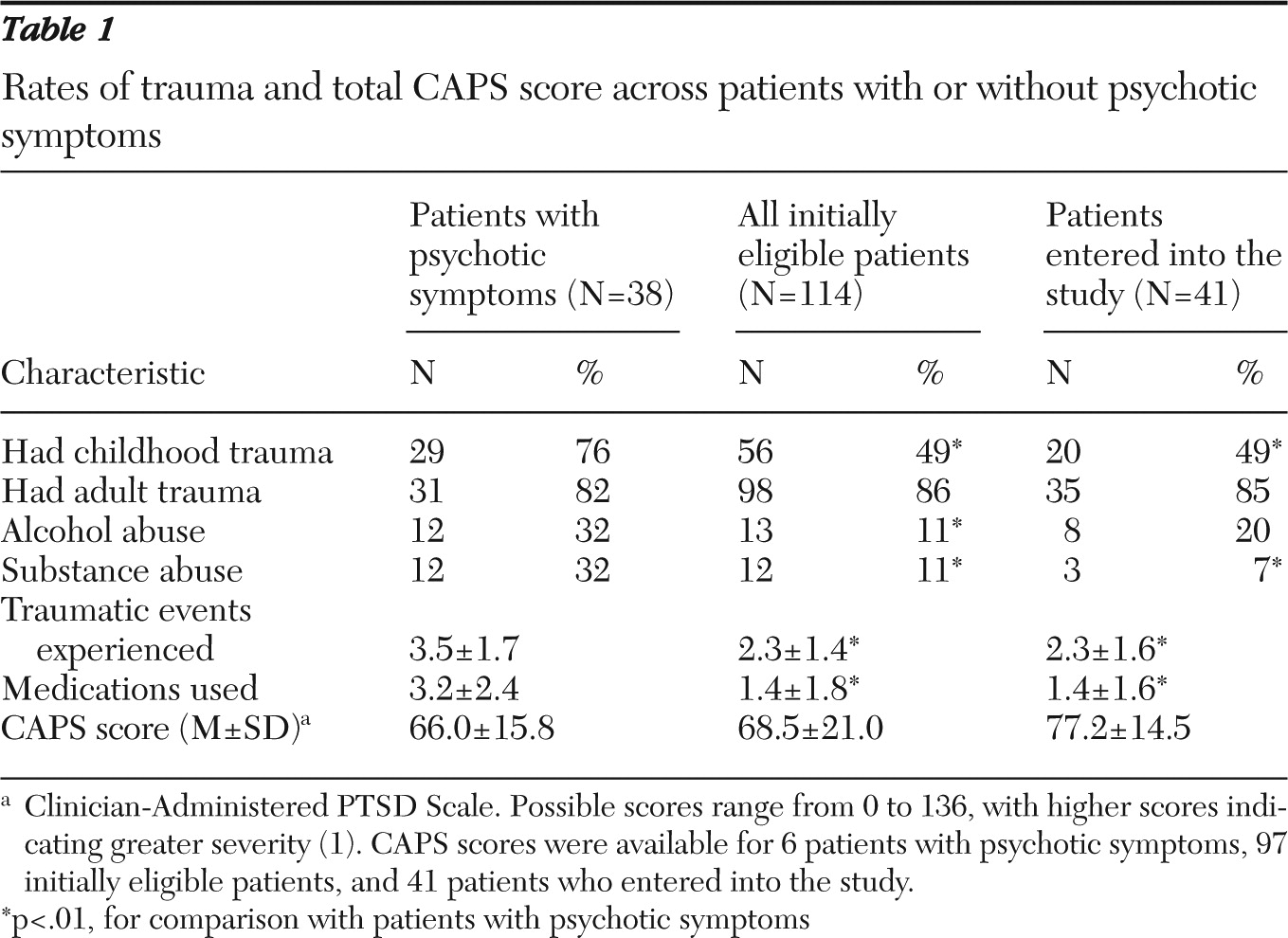

We compared applicants who had psychotic symptoms (N=38) who had all others remaining eligible for the parent study after the initial interview (N=114) (

Table 1). Applicants with psychotic symptoms were more likely to be male (N= 24 of 38, 63%) than study-eligible applicants (N=36 of 114, 32%;

χ2=11.9, df=1, p<.01). The group with psychotic symptoms reported significantly more traumatic events (3.5 versus 2.3; t=4.02, df=150, p<.01) and were more likely to report childhood trauma (

χ2=8.55, df=1, p<.01) but not adult trauma. The CAPS score did not differ significantly between groups. The six individuals with psychotic symptoms who received CAPS ratings all met PTSD criteria (range=37–82 out of 136, with higher scores indicating greater severity). Applicants with psychotic symptoms had taken significantly more lifetime medications (N=25, mean of 3.2 medications) compared with study-eligible patients (N=104, mean of 1.4 medications; t=4.2, df=127, p<.01) and were significantly more likely to report lifetime substance abuse (32% versus 11%;

χ2=14.86, df=1, p<.01) and alcohol abuse (32% versus 11%;

χ2=13.54, df=1, p<.01). The intake records may yield underestimation of prevalence, and clinicians rarely discriminated between substance or alcohol dependence or abuse. However, none of the patients administered the SCID met alcohol or substance dependence criteria.

Because study entrants (N=41) had definitive diagnoses and did not have psychosis, we compared this group with the group with psychotic symptoms (N=38). Applicants with psychotic symptoms were more often male (63%) compared with treatment study patients (24%) (χ2=12.09, df=1, p< .01). The group with psychotic symptoms was significantly more likely to report childhood trauma (76% versus 49%; χ2=6.35, df=1, p<.01), whereas reported adult trauma did not differ between groups. Applicants with psychotic symptoms recounted significantly more traumas (3.5) than did study patients (2.3; t=3.07, df=77, p<.01) and reported having taken more medications (3.2 versus 1.4; t=3.5, df=57, p<.01). No significant difference between groups was found in CAPS scores. Applicants with psychotic symptoms reported more lifetime substance abuse (32% versus 7%; χ2=11.11, df=1, p<.01) and a trend for more alcohol abuse (32% versus 20%; χ2=3.6, df=1, p=.06).

Discussion

Psychotic symptoms were unexpectedly prevalent among applicants presenting to our PTSD study seeking psychotherapy for the effects of life traumas. Applicants often minimized psychotic symptoms when discussed in the context of psychosis, yet acknowledged them in the context of trauma. They saw their trauma history as key to their presentation and conveyed that prior clinicians had not taken these trauma histories seriously. Eighty-two percent (N=28 of 34) reported severe paranoia—which exceeded the expectable mistrust of traumatized individuals with PTSD—yet still voluntarily sought study treatment. The results of our exploration suggest that our study was appealing because it offered nonmedication treatment and because the diagnosis of PTSD offered a nonstigmatizing, normalizing framework.

Of those with psychotic symptoms, 66% reported a psychotropic medication history—a likely underestimate because of insufficient chart information for 13 individuals—and use of more than three medications per person. Only three (8%) reported no medication history. None currently took medication, and most who had were not interested in restarting it. Several individuals we screened reported specific dissatisfaction with pharmacotherapy and refused to take medication in the future.

Applicants sought help for and acknowledgment of their traumatic past and perceived any psychotic symptoms as symptoms of trauma. The PTSD diagnosis may have been perceived as nonstigmatizing and therefore acceptable, whereas a diagnosis of psychosis was not. One applicant explained that he found the stigma of a psychotic diagnosis quite distressing yet was willing to accept treatment for PTSD, a model consistent with his own understanding of his problems. Trauma may provide a normalizing, external explanation for symptoms, in contrast to “inner” psychosis, which may be perceived as a deficit or character flaw.

Psychosis does not preclude PTSD. Most of the individuals with psychotic symptoms reported objective traumatic events (95%), and 84% reported that multiple traumatic events preceded their psychopathology. Most who completed the intake interview reported multiple PTSD symptoms, and all evaluated by CAPS met

DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. Research indicates high rates of PTSD among individuals considered to have serious mental illness; however, PTSD is often overlooked and understudied despite its possible exacerbation of overall symptomatology (

4,

5). Although patients suffering from delusional symptoms may distort reality, Goodman and colleagues (

6) showed that reliability of reports of trauma among patients with psychosis was comparable with that of nonpsychotic trauma survivors. Our study suggests that persons with psychotic symptoms may seek help for trauma-related distress and that clinicians should acknowledge the reported trauma and treat associated distress.

Psychotic symptoms may actually represent a response to trauma rather than a separate symptom pattern. Recent preliminary research has studied PTSD with psychotic features as a new potential diagnostic category (

7). Auditory hallucinations and delusions are considered common in combat-related PTSD (

8), and paranoia may be viewed as a positive survival strategy (

9). In addition, a recent literature review found evidence of a correlation between childhood trauma and psychosis, concluding that hallucinations and delusions may be conceptualized as traumatic intrusions and schemas (

10). Note that most (76%) of the applicants with psychotic symptoms reported multiple childhood traumas, a pattern significantly different from the groups without psychosis.

Conclusions

The individuals with psychotic symptoms in this study were seeking help for reported traumas, directly related their symptoms to their trauma history, refused medication, and were willing to engage in psychotherapy. At least 79% of our sample reported previous mental health treatment, and all of them felt that it had been insufficient. The study likely attracted such individuals because it was a trauma-focused, nonmedication, psychotherapeutic trial that they deemed appropriate for addressing their distress. A trauma-informed framework for treating PTSD and comorbid psychotic disorders has shown effectiveness in over 30 randomized controlled trials (

11), and a recent pilot study of exposure-based cognitive-behavioral therapy showed promise for patients with PTSD and comorbid schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (

12). The individuals who presented to our study might benefit from such an approach as well.

The study limitations are many. Our sample was small, the design of our research intake process precluded definitive diagnosis of ineligible applicants, and we lacked follow-up on these individuals. All data were examined retrospectively, and detailed histories and current symptomatology were not always obtained. Our results require confirmation by replication. Despite these limitations, our exploratory findings suggest further research that might lead to greater engagement of a suffering, undertreated population.