Lipid biology and role in atherosclerosis

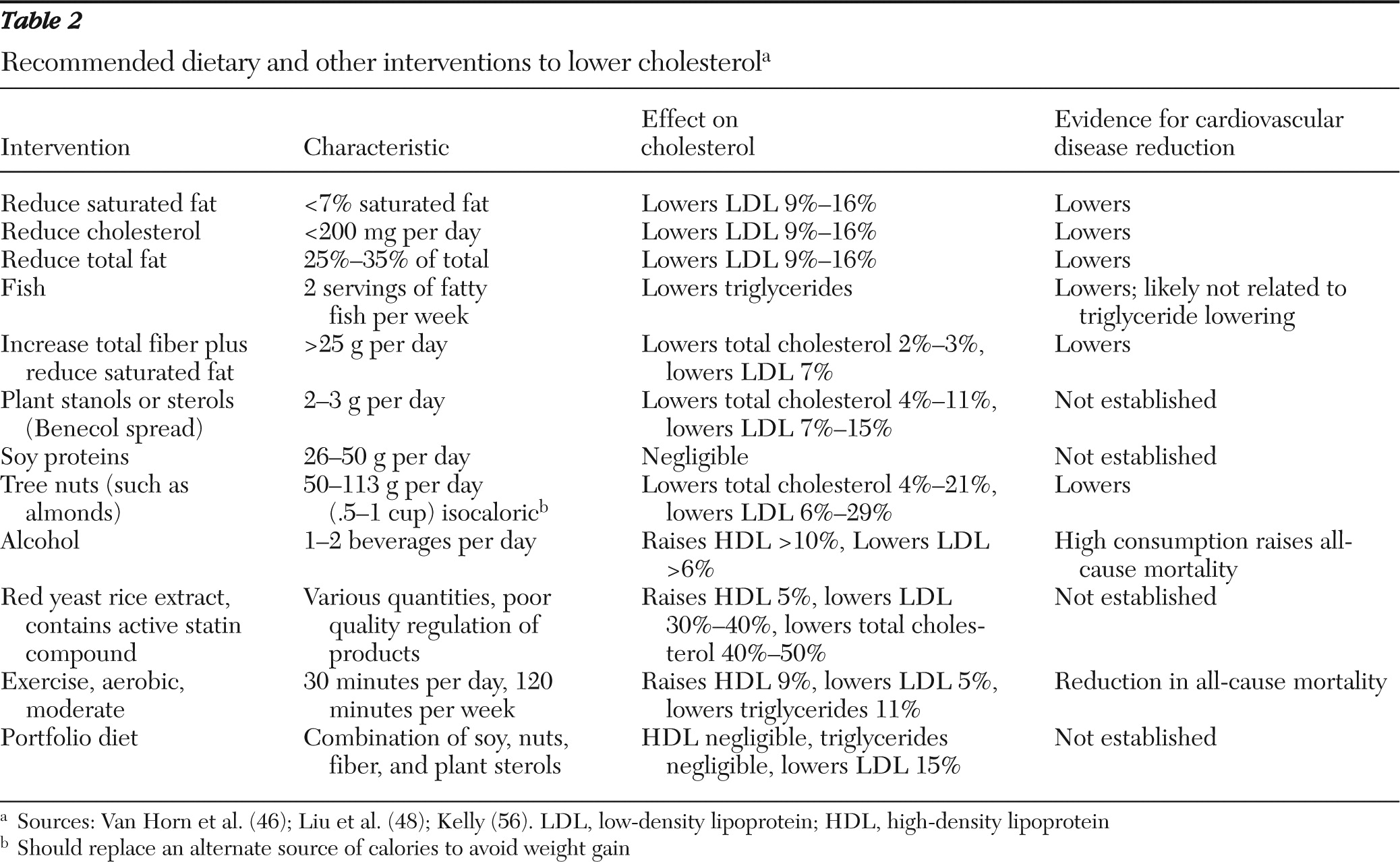

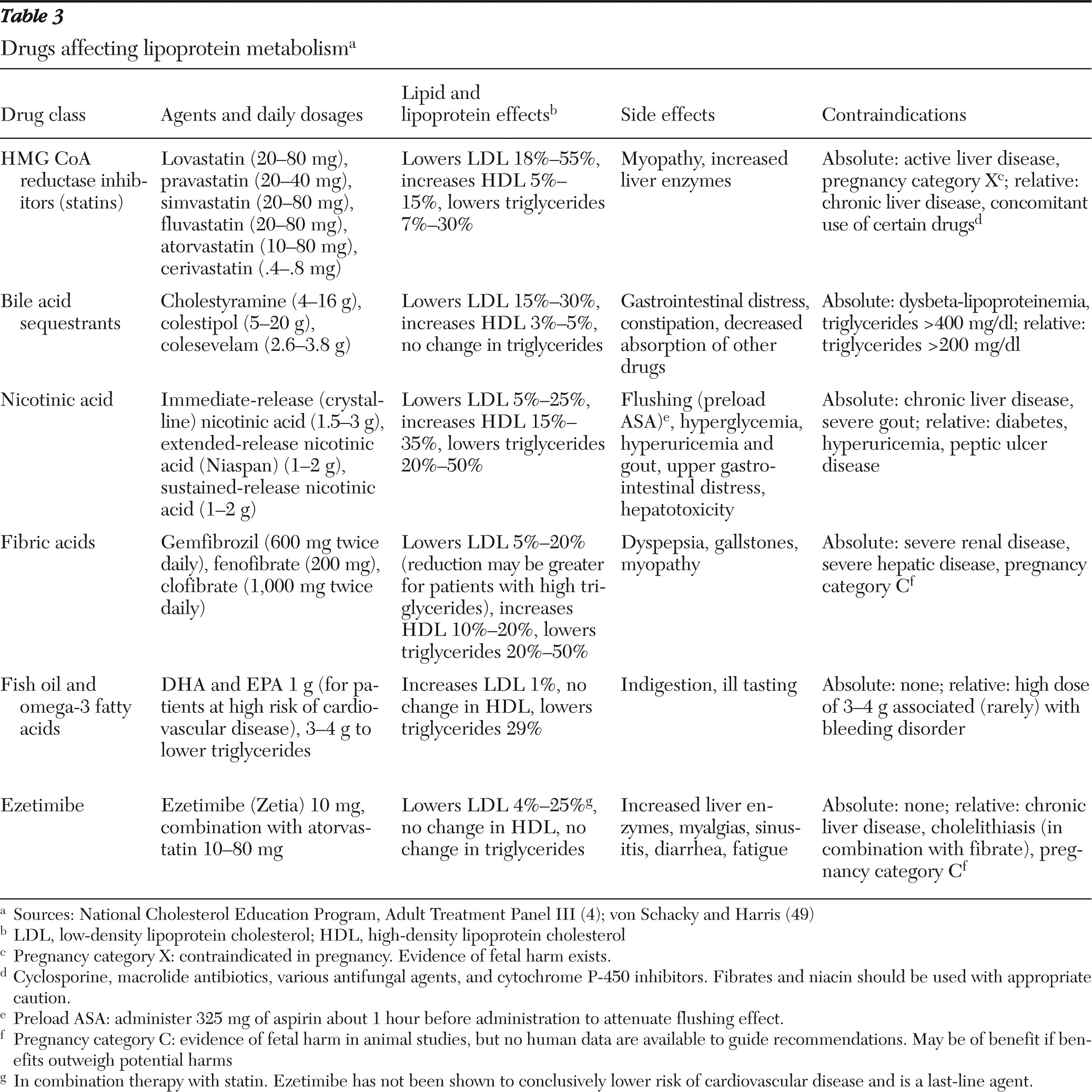

Cholesterol is a waxy compound manufactured by the intestines and the liver, is an essential component of cell membranes of mammals, and is present in nearly all animal products consumed (eggs, meat, milk, and so forth). HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (“statins”) block the rate-limiting step of endogenous cholesterol production. Cholesterol is not water soluble and needs lipoproteins for transport to different tissues. Lipoproteins are traditionally identified by their relative density and (in ascending order) are noted to be chylomicrons, VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein), IDL (intermediate-density lipoprotein), LDL, and HDL. Of these, LDL is the most prevalent and the most scrutinized for its role in atherosclerosis. However, other non-HDL lipoprotein particles also contribute to atherosclerosis risk, particularly among patients with high triglycerides. Indeed, LDL levels in such patients may be misleadingly low. Triglycerides are the primary components of dietary fats, transported in chylomicrons and VLDL, and are closely associated with abnormal glucose metabolism. As concentrations increase, triglycerides are degraded to lipoproteins of various densities containing cholesterol and have been weakly linked to cardiovascular disease.

Cholesterol-rich LDL and other particles (IDL and VLDL) that are not absorbed by body tissues for metabolism can enter the vascular wall (particularly if it is already damaged by smoking, hypertension, or diabetes). Cholesterol accumulates in arterial linings to eventually form atherosclerotic plaques. This process leads to the progressive narrowing of blood vessels, resulting in claudication or angina and eventually plaque rupture, clot formation, and myocardial infarction or stroke. Cholesterol can be removed from tissues through the actions of HDL (reverse cholesterol transport) and transported to the liver for processing and conversion to bile.

Measured total cholesterol is the sum of cholesterol present in all lipid particles, including chylomicrons. Total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL are measured directly in common laboratory tests. Because of the cost, LDL is usually calculated by using measures of the other three, or it can be directly measured. Total cholesterol and HDL vary little with respect to fasting status; however, triglycerides vary widely. VLDL is estimated to be one-fifth of total triglyceride concentration, as long as triglycerides are <400 mg/dl (

28). The formula (equation 1) for approximating LDL concentration (known as the Friedewald formula) is as follows (TC is total cholesterol, cLDL is calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG is triglyceride concentration, and HDL is high-density lipoprotein cholesterol):

cLDL ≈ TC − HDL − VLDL (1)

VLDL is almost equal to triglycerides divided by 5. Therefore, substituting VLDL for TG/5 allows approximation of LDL concentration (cLDL) with TC, HDL, and TG concentrations (equation 2):

cLDL ≈ TC − HDL − triglycerides/5 (2)

Because of this principle, LDL can be calculated from a fasting patient by subtracting HDL and triglycerides divided by 5 from the value for total cholesterol, which yields what is known as the cLDL (calculated LDL). At lower triglyceride concentrations, IDL and chylomicrons make up an exceedingly small fraction of total cholesterol and are not measured. Because of fluctuations in triglyceride levels, specimens from nonfasting patients cannot be used to reliably estimate cLDL (

29).

Well-established studies have linked cLDL, total cholesterol, and HDL (inversely) to rates of cardiovascular disease mortality, independent of other risk factors (

4). There is evidence that reducing cLDL, especially among adults with moderate to high risk of cardiovascular disease, results in significant reductions (up to 50%) in death or myocardial infarction after treatment (

30).

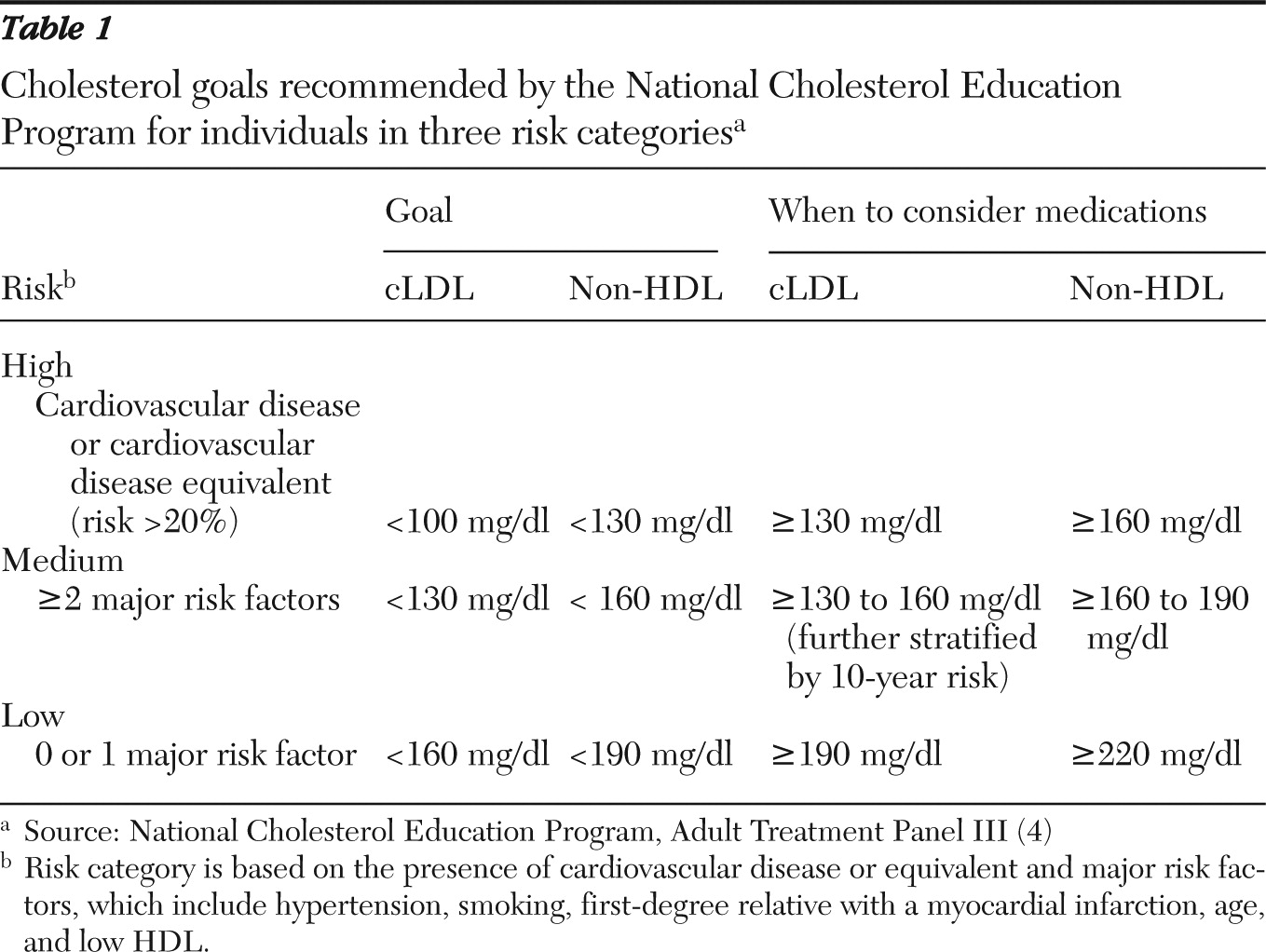

Non-HDL cholesterol, defined as serum total cholesterol minus HDL, appears to represent the portion of total cholesterol most clearly related to overall cardiovascular disease risk. Measured or cLDL may not accurately represent cardiovascular disease risk for persons with even modestly elevated triglycerides and could lead to undertreatment. This is especially true for persons with metabolic syndrome or exposure to second-generation antipsychotics. Guidelines for the treatment of non-HDL cholesterol are achieved through the same diet, lifestyle, and pharmacotherapy options as for LDL therapy and may represent a better treatment target than cLDL values for persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Treatment targets for non-HDL cholesterol are typically set 30 mg/dl higher than LDL goals and may be a surrogate benchmark for nonfasting patients. Although current guidelines favor the use of cLDL targets in initiating and measuring therapy, the use of nonfasting non-HDL cholesterol as a therapy target may offset challenges in arranging for follow-up fasting specimens among persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

Screening among persons with persistent mental illness

For adults in the general population, screening for dyslipidemia every five years is recommended. Current guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend screening men who have an average risk of cardiovascular disease every five years beginning at age 35 and screening women who have an average risk beginning at age 45. Adults with elevated risk, as defined by either a cardiovascular disease risk-equivalent (a ten-year risk of about 20% for major myocardial infarction, stroke, or death; or the presence of diabetes, preexisting cardiovascular disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, peripheral arterial disease, or carotid artery stenosis) or a major risk factor (hypertension, myocardial infarction for a male first-degree relative by age 55 or a female first-degree relative by age 65, smoking, and HDL<40 mg/dl), should be screened beginning at age 20 (class B recommendation: there is moderate to high certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial) (

31). By some estimates, these criteria would include up to 60% of persons seen annually at community mental health centers (

32,

33), regardless of antipsychotic use. There is evidence of a markedly elevated risk of diabetes or cardiovascular disease independent of exposure to second-generation antipsychotics among persons with severe and persistent mental illness (

34,

35).

The consensus conference of the American Diabetes Association and the American Psychiatric Association recommended that patients who are taking second-generation antipsychotics undergo screening for dyslipidemia (

36). [A table summarizing the recommendations is available online as a data supplement to this article.] Some experts now recommend cholesterol screening every six months for individuals taking second-generation antipsychotics after one year of treatment if baseline or follow-up serum cLDL or non-HDL concentration is greater than 130 mg/dl or 160 mg/dl, respectively (

37,

38).

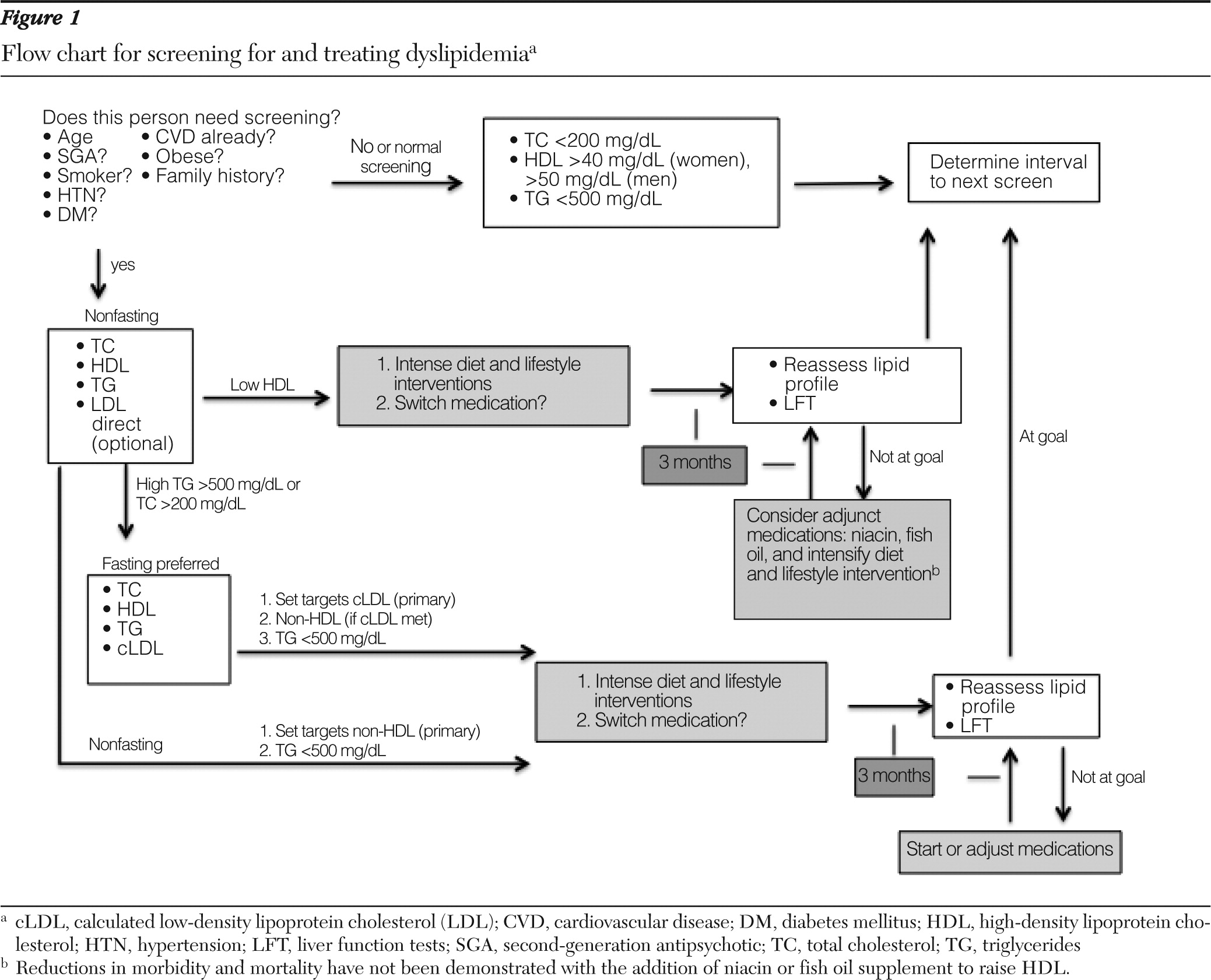

Rarely is the triglyceride level greater than 500 mg/dl, at which point it is associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis. Combined with checking hemoglobin A1C as a diagnostic indicator of diabetes (

39), screening for dyslipidemia with non-HDL cholesterol may now be offered to nonfasting clients without the inconvenience of their having to return later for a fasting measurement (

40). Individuals who screen positive for dyslipidemia (total serum cholesterol >200 mg/dl for males and females, HDL <40 mg/dl for males and <50 mg/dl for females, or triglycerides >500 mg/dl for males and females) should undergo follow-up fasting measurement of triglycerides and cLDL to guide interventions and referrals. Direct or add-on LDL measurement is a possibility, but it has not been rigorously evaluated in large epidemiologic studies, and there is some variance in laboratory assay standards.