One theoretic limitation of positive-screen–based quality indicators is that they might preferentially reward systems that identify fewer patients through screening.

Table 1 shows how bias due to variation in the sensitivity of screening programs across health systems could undermine the validity of positive-screen–based quality indicators. Three hypothetical systems (A–C) with identical patient populations and identical true prevalence rates of a behavioral condition are modeled. Compared with systems B and C, system A has a more sensitive screening program, resulting in a twofold higher prevalence of positive screens (10% versus 5%). Therefore, although systems A and B have identical performance on a positive-screen–based quality indicator (50% of patients with positive screens have appropriate follow-up), system A identifies and offers follow-up to twice as many patients with the condition (5,000 versus 2,500). Comparison of systems A and C demonstrates how A, with a more sensitive screening program, could perform worse on a positive-screen–based quality indicator (50% versus 80%) despite identifying and offering follow-up care to more patients with the condition (5,000 versus 4,000).

One strategy to improve the validity of positive-screen–based quality indicators and avoid bias due to differing denominators (“denominator bias”) is to require use of a specific validated screening questionnaire and threshold to standardize the denominator (

13). This strategy is used by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for alcohol misuse as well as for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

11,

14). However, recent research has demonstrated that despite use of a uniform screening questionnaire and threshold for a positive screen, the sensitivity of alcohol screening programs may vary across VHA networks (

15), likely because of differences in how screening is implemented in practice, such as with nonverbatim interviews versus with questionnaires completed on paper (

16). Variation in the sensitivity of screening programs could undermine the validity of positive-screen–based quality indicators, but this has not been previously evaluated.

This study used VHA quality improvement data to determine whether variability in the prevalence of positive screens for alcohol misuse undermined the validity of a positive-screen–based quality indicator of follow-up for alcohol misuse (that is, with denominator bias). If denominator bias existed in the VHA despite high rates of screening with a uniform screening questionnaire and threshold, it would suggest that positive-screen–based quality indicators might unintentionally systematically reward health systems that identified fewer patients with alcohol misuse due to poorer-quality alcohol-screening programs. If this were true, positive-screen–based quality indicators for other behavioral conditions would need to be similarly evaluated.

Discussion

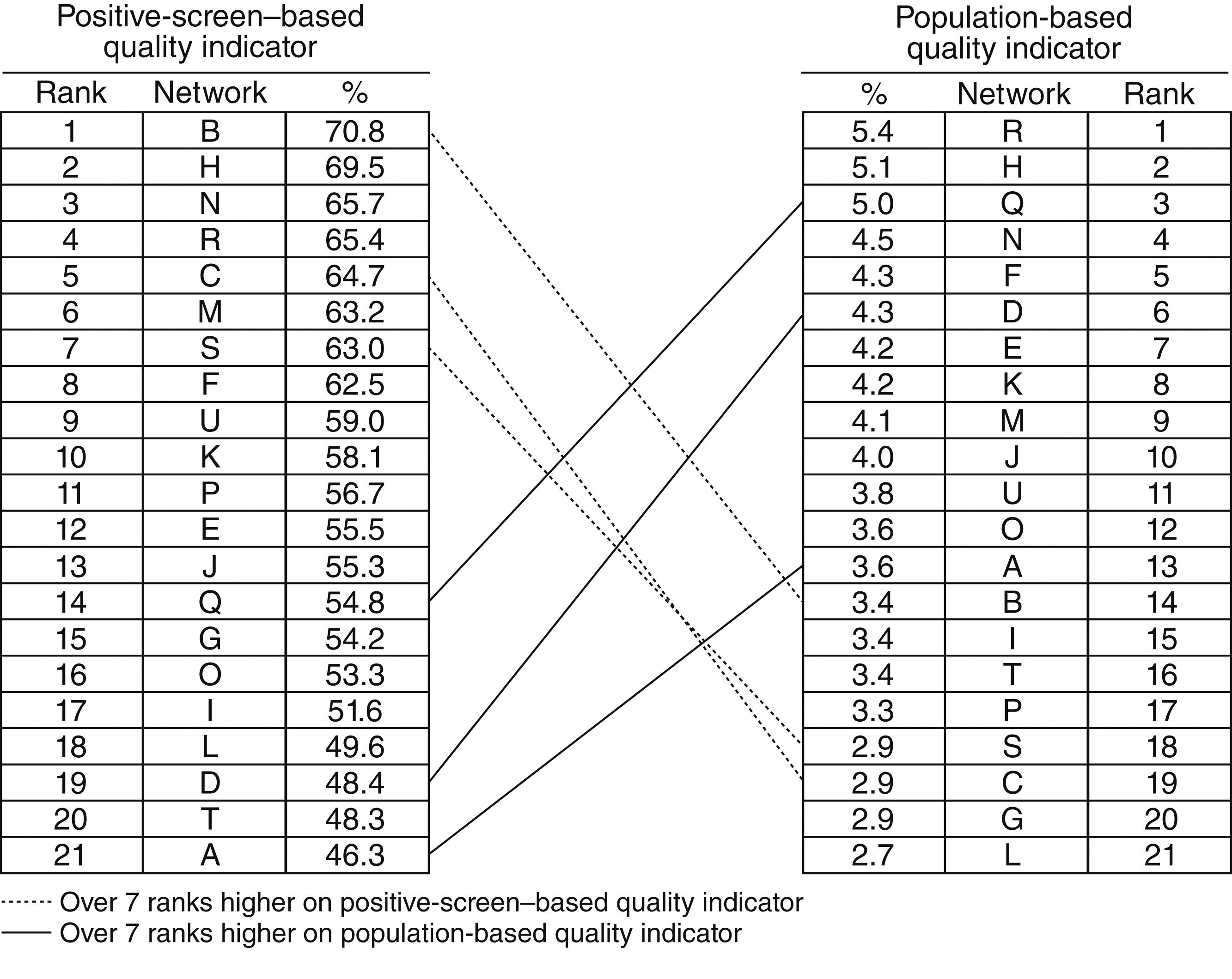

This study demonstrated important limitations of quality indicators of follow-up care for alcohol misuse that use the number of patients with positive alcohol screens as the denominator. One limitation is that network performance on the positive-screen–based quality indicator did not reflect the proportion of patients who had alcohol misuse identified and appropriate follow-up documented. Moreover, the magnitude of the observed inconsistencies was clinically meaningful. For example, two networks performed almost identically on the positive-screen–based quality indicator (64.7% and 65.4%) even though one identified and offered appropriate follow-up for alcohol misuse to almost twice as many patients (5,411 versus 2,899) per 100,000 eligible for screening. Given that some VHA networks screen more than 450,000 patients a year, two networks with comparable sizes and performance on a positive-screen–based quality indicator could differ by more than 11,000 patients identified and offered care for alcohol misuse each year. Moreover, results suggest that the positive-screen–based quality indicator was biased by insensitive screening programs: the better that networks performed on the positive-screen–based quality indicator compared with the population-based quality indicator, the lower their screening prevalence of alcohol misuse (that is, the less likely they were to identify alcohol misuse by screening).

Alcohol screening and brief counseling interventions have been deemed the third highest prevention priority for U.S. adults (

28,

29) among practices recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (

30). Positive-screen–based quality indicators of follow-up for alcohol misuse have been put forth by the Joint Commission (JC) (

9), as well as by the National Business Coalition on Health (NBCH) to increase alcohol screening and follow-up (

12). Our results demonstrate potential problems with these quality indicators. In addition, whereas the VHA has required use of a common alcohol screening questionnaire and threshold to standardize the denominator of its positive-screen–based quality indicator, JC and NBCH have not specified standard alcohol screening questionnaires or thresholds (

9,

12). Allowing health care systems to use different screens will likely result in even greater variability in the prevalence of positive screens for alcohol misuse, which could further bias positive-screen–based quality indicators (

23–

26).

These findings also call into question other quality indicators for behavioral health care. Positive-screen–based quality indicators are increasingly used for depression and other behavioral conditions (

31,

32). These measures, developed from clinical guidelines and expert opinion (

13), are often paired with measures to encourage behavioral screening because underidentification is one of the greatest barriers to high-quality behavioral health care (

2). However, no previous study to our knowledge has evaluated whether positive-screen–based quality indicators for follow-up on behavioral conditions preferentially reward health systems that identify fewer patients with the condition of interest, despite known limitations of other quality indicators based on clinical guidelines (

33–

35). Furthermore, this bias could affect “diagnosis-based” behavioral quality indicators that use the number of patients with diagnosed behavioral conditions as the denominator (

35), such as the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set alcohol or other drug measures used by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (

36).

This study suggests that alternatives to positive-screen–based quality indicators for behavioral health conditions are needed. The American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement has proposed a population-based quality indicator, similar to that used in this study (

37), which encourages identification as well as appropriate follow-up of alcohol misuse. However, population-based quality indicators can seem counterintuitive to clinicians because follow-up is evaluated for all patients regardless of their need (that is, among patients with positive or negative screens). Further, population-based quality indicators could be biased because of differences in clinical samples. Therefore, although adjustment did not meaningfully change results in this study, population-based quality indicators may need to be case-mix adjusted. Moreover, all measures that rely on provider documentation for the numerator could be biased by electronic medical records that encourage identical documentation of follow-up regardless of care provided.

Patient report of appropriate care for alcohol misuse on surveys that include standardized alcohol screening is likely to be the optimal quality indicator for follow-up of alcohol misuse (

38). Mailed patient surveys are used to assess smoking cessation counseling, and Medicare is planning to use surveys to assess other preventive counseling (

39). Alcohol-related advice is a key component of evidence-based brief alcohol counseling (

40), and the VHA has screened for alcohol misuse and measured receipt of alcohol-related advice on patient surveys since 2004 (

41). This survey administers the AUDIT-C in a standard fashion and then asks about alcohol-related advice. Standardized screening on a mailed survey avoids differences in screening methods across systems, and patient survey measures are not biased by variability in provider documentation (

38).

This study had several limitations. First, both quality indicators relied on medical record reviews of clinical documentation of appropriate follow-up; there was no external gold standard for alcohol-related discussions. The quality of documented alcohol-related discussions is unknown, especially when documentation of follow-up is rewarded, as in the VHA since 2007 (

11). In addition, this study compared performance at the network level and used data from a 30-month period to improve the precision of estimates (

42), obscuring possible variability across facilities and time. Further research is needed to explore other factors that bias quality measurement, particularly the severity of identified alcohol misuse and the prevalence of identified alcohol use disorders (

23–

26). Finally, the generalizability of these findings from the VHA to other health systems is unknown. However, other health systems are increasingly implementing screening with the AUDIT-C (

11,

13,

18,

41,

43–

46), and incentives for electronic health records (

47–

50) and Medicare reimbursement for annual alcohol screening (

51) will likely increase implementation and monitoring of alcohol screening and follow-up.

Nevertheless, these findings regarding first-generation quality indicators of follow-up care for alcohol misuse can inform development of evidence-based second-generation measures. Whereas several national organizations have developed quality indicators for follow-up of alcohol misuse (

9,

12,

37), others—such as the National Quality Forum and NCQA—have not, in part because of a lack of information on the optimal approach to measuring the quality of appropriate follow-up care. This study evaluated the convergent validity between positive-screen–based and population-based quality indicators, an essential step in improving quality measurement for behavioral conditions (

21). Findings suggest that positive-screen–based quality indicators systematically favor health systems with insensitive alcohol screening programs, undermining efforts to improve identification of alcohol misuse. Other positive-screen–based quality indicators for behavioral conditions may have similar limitations. Because underrecognition of behavioral conditions is a critical barrier to high-quality care (

2), positive-screen–based quality indicators for other behavioral conditions should be evaluated in future research.