The efficacy of second-generation antipsychotic medication is neither robust nor consistent (

1,

2). There is considerable heterogeneity in treatment response to antipsychotic medication, and a substantial number of patients with schizophrenia who are receiving adequate trials of medication continue to experience psychotic symptoms that interfere with their functioning (

3–

5). The percentage of patients who respond to antipsychotic medication is less than half, and treatment response declines over time (

6,

7). Drug trials examining second-generation antipsychotics have been hampered by high attrition rates; dropout exceeding 50% is the norm (

8,

9). High dropout rates have been attributed to intolerable side effects that include weight gain, other metabolic effects, and extrapyramidal effects, indicating substantial limitations in the effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics (

8).

Furthermore, the presence of any persistent symptoms of psychosis is a marker of poorer prognosis (

10). For example, the lifetime risk of suicide for patients with schizophrenia is 5% (

11), although suicidality can be as high as 13% (

12). In addition, patients with persistent positive symptoms experience more hospitalizations (

13) and longer inpatient stays (

14,

15). Not only do patients with medication-resistant psychosis have poorer prognoses, but the cost of their care is higher as a result of increased hospitalization.

Neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia have been associated with functional outcome (

16). However, much less attention has been paid to the role that psychiatric symptoms may play in predicting functional outcome. The data suggest a relatively clear role for negative symptoms, which mediate the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome (

17,

18). But the role of persistent positive symptoms is less clear. Some have reported that positive symptoms appear to interfere less than negative symptoms with social and work functioning (

19,

20), whereas others have found that ongoing positive symptoms are associated with poorer occupational functioning (

21) and reduced social functioning (

22). Further research is needed to clarify the impact of persistent positive and negative symptoms on functional outcome and how these symptoms may be differentially affected by treatment.

What is CBT for psychosis?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for psychosis is a time-limited, present-oriented approach to psychotherapy that teaches patients that there is a relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behavior. The process involves therapists and patients working collaboratively to develop a shared understanding of the problem or a case formulation, set goals, and learn techniques and strategies to reduce or manage symptoms. Specific CBT approaches used in treating schizophrenia include psychoeducation and normalization, or helping patients understand that psychotic experiences exist on a continuum with nonpsychotic experiences; cognitive restructuring, or finding connections between activating events, beliefs, and consequences; reattribution of hallucinations, or discovering beliefs about the origin of experiences and looking for an explanation; behavioral experiment or reality testing; and development of coping strategies (

23).

Despite variation in the content of CBT techniques, the four leading treatment manuals (

23–

26) share common elements, such as cognitive conceptualization of psychotic symptoms, psychoeducation about the nature of the illness, establishment of a strong therapeutic alliance through collaborative empiricism, and relapse prevention (

27). In addition, the shared goals of CBT include modifying patients’ distorted beliefs about delusions and hallucinations so as to decrease the negative consequences of these symptoms on their daily functioning. For example, the first step is usually to monitor the frequency, intensity, and duration of psychotic symptoms, their triggering events, and the conditions that maintain them. The next step includes a combination of cognitive restructuring, normalizing, reality testing, and reappraisal or reattribution of the experience, depending on the conceptual framework being utilized.

Despite the heterogeneity of CBT approaches, an impressive number of randomized controlled trials have found that adding CBT to standard care (including medication) can reduce psychiatric symptoms such as depression (

28) and negative symptoms (

29,

30). In addition, CBT can reduce the duration of hospital stays (

29) and improve general social functioning (

31). Both hallucinations and delusions respond well to CBT, and CBT appears to be superior to supportive counseling in improving symptoms (

32). Support for CBT to treat psychosis has accumulated over the years, and many national health guidelines recommend CBT for the treatment of schizophrenia. These guidelines include those from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (

33) in the United States, the National Board of Health and Welfare (

34) in Sweden, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (

35) in the United Kingdom, and the Canadian Psychiatric Association (

36).

Summary of previous meta-analyses

As of May 2012 when this review was undertaken, eight meta-analyses examining the effectiveness of CBT for psychosis had been published. Most meta-analyses found that CBT reduces positive symptoms (

37–

39), negative symptoms (

27), and general psychopathology (

40,

41). Because a sufficient number of primary research studies have been published, meta-analyses have addressed various features of CBT for psychosis. For example, the review by Wykes and colleagues (

40) addressed outcome as a function of methodological rigor and noted that studies with more rigorous methodology found a lower effect size. Similarly, the meta-analysis by Sarin and colleagues (

41) examined the durability of CBT and found evidence for enduring efficacy—that the effect of CBT is delayed and that improvements can be seen a few months after treatment termination. In addition, CBT involving at least 20 sessions was found to have better outcomes.

Only one meta-analysis concluded that CBT was not effective in reducing symptoms in schizophrenia (

42). However, this meta-analysis has a number of important limitations. First, the authors excluded important studies and focused only on end-of-treatment scores (

43). Moreover, they pooled results from CBT with several diagnostic groups and failed to distinguish studies of simple efficacy from studies of relative efficacy.

Purpose of this meta-analysis

Taken together, there is overwhelming evidence that CBT for psychosis is effective, with effect sizes ranging from .22 to .91 (

27,

40). At present, an overwhelming number of published studies support the effectiveness of CBT for the treatment of positive symptoms. Although various reviews have addressed several important features of this body of evidence, none has yet addressed the clinically important feature of CBT for outpatients with medication-resistant symptoms. Ironically, this common clinical presentation has been assessed in most studies of CBT for psychosis. A standard definition of medication-resistant schizophrenia and what constitutes treatment response is lacking (

44). However, the number of patients who continue to experience psychotic symptoms that interfere with their functioning is estimated to be between 20% and 50% (

3,

45–

47). The aim of this meta-analysis was to examine the effects of CBT in the treatment of outpatients who do not show a complete response to medication.

Methods

Trial inclusion

Ninety-eight publications were identified and reviewed. Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: at least one CBT group must be compared with a control group (waiting list, treatment as usual, or another therapeutic treatment); the study sample must contain a majority of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder; all patients must continue to exhibit positive symptoms despite an adequate trial of antipsychotic medications (stable medication for at least three months); assignment must be random; at least one validated outcome measure of positive symptoms (hallucinations or delusions) must be used; and results must provide sufficient information to compute common effect size statistics. Sixteen articles met inclusion criteria. [A figure illustrating the selection of articles for this meta-analysis is presented in an online

data supplement to this article.]

Systematic searches of the Cochrane Collaborative Register of Trials, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and PubMed were performed by using the following keywords and method: (schizo* or schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or psychosis) and (cognitive therapy or cognitive-behavior therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy) and (random or randomized controlled trial or clinical trial). In addition, the reference lists of several published reviews were examined (

38–

41). The author of one known registered trial of CBT for persistent positive symptoms was contacted, but data on the primary endpoint of the study were not yet available (personal communication, Klingberg S, July 13, 2012). Published studies with an abstract in English up to the end of May 2012 were reviewed.

Coding procedures

Studies were coded for author and year of publication; total participants; random assignment; blind assessments; number of CBT sessions; type of control group; outcome measures used; duration between baseline, posttreatment, and follow-up; and medication status. The total number of participants at baseline and posttreatment was calculated separately to determine the number of dropouts. To ensure a level of medication adequate to meet the criteria for medication resistance, chlorpromazine equivalence was calculated whenever possible.

Criteria for “medication resistant”

Although the criteria used to define medication resistant varied slightly between trials, most studies used “medication resistant” to denote cases in which symptoms persist despite adequate trials of medication. In this literature, an adequate trial was defined as good adherence at dosages at or above the equivalent of a 300-mg daily dose of chlorpromazine equivalent (

48). In addition to the above definition, all patients treated with clozapine were considered to have medication-resistant psychosis.

Types of control group

The control group was defined as treatment as usual or an adjunct treatment that had been hypothesized to be inactive for the main outcome. Treatment as usual was typically the treatment that patients would have received from mental health services if they had not participated in the study. Although treatment as usual varied greatly depending on the country and catchment area in which the study was conducted, it usually consisted of a combination of case management and antipsychotic medication. Effect sizes were calculated separately to compare CBT to treatment as usual or to control adjunct treatments to determine whether the choice of control condition influenced the outcome. Control adjunct treatments, included to distinguish between the specific effects of general psychotherapy and CBT, have included psychoeducation, befriending, and supportive counseling. Psychoeducation consists of different modules designed to promote understanding of the illness and symptoms of schizophrenia, knowledge of medication and side effects, relapse prevention, and coping with symptoms (

49). In the befriending intervention, the therapist is empathic, warm, and nondirective. In the befriending intervention, psychotic or affective symptoms are not directly addressed; instead the sessions focus on neutral topics, such as hobbies, sports, and current affairs (

50). In supportive counseling, the therapist shows noncritical acceptance, warmth, genuineness, and empathy through basic skills such as reflecting, empathizing, and summarizing (

51).

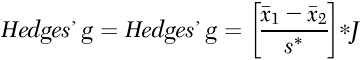

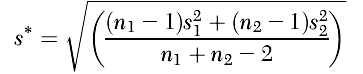

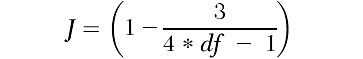

Effect size calculation

The standardized mean difference corrected for bias, Hedges’ g (

52), was calculated with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 2.2.064. Although both Cohen’s d and Hedges’ g pool variances on the assumption of equal population variances, Hedges’ g uses N–1 for each sample instead of N, which provides for a better estimate, especially for smaller sample sizes (

53). The effect size statistic was computed as the difference between the treated mean change in the CBT group and the control group, divided by the pooled standard deviation, multiplied by a correction factor. Hedges’ g was calculated from the following equation:

where

is the mean change of the treated group,

is the mean change of the control group, s* is the pooled standard deviation, and J is the correction factor.

Because the samples in these studies were selected for patients’ medication-resistant positive symptoms, the primary outcome measure was positive symptoms, which were assessed by using reliable measures such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). However, other measures of positive symptoms, such as the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scales, Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale, and Voice Compliance Scale, were also included when PANSS and BPRS scores were unavailable. When general symptoms were reported, a secondary effect size was calculated in addition to the effect size for positive symptoms. Effect sizes were calculated at posttreatment and at follow-up (between three and 18 months). Following convention, effect sizes were coded such that a positive sign indicates that the CBT group improved more than the control group. For two of the 12 trials, outcome measures were extracted as dichotomous data, and log odds ratios were computed and then converted to standardized mean differences (

50,

54). In these two trials, clinical improvement was defined as greater than 50% improvement in psychotic symptoms in both severity and number of symptoms.

Trial quality

Research suggests that the quality of a trial, as well as methodological heterogeneity between studies, may affect outcome and thus influence effect size (

40,

55). One measure of quality is whether blind assessments are used. It is assumed that trials with raters who are blind to group allocation will be of higher quality than those in which raters are not blind to condition. Thus trial quality was coded to evaluate raters’ influence on effect sizes. Trial quality was operationalized as whether raters were blind to group allocation and was examined as a moderator variable.

Results

Description of studies

The search identified 98 references, of which 16 published articles describing 12 trials met the inclusion criteria for this analysis (

29,

49–

51,

54,

56–

66). A total of 639 individuals completed the baseline assessment, and 552 completed the posttreatment assessment, yielding a dropout rate of 14%. Of the 12 trials, four lacked independent assessors blind to the treatment condition. In two trials, CBT was compared with two control conditions, treatment as usual and active psychotherapy.

Table 1 summarizes information about the 12 trials.

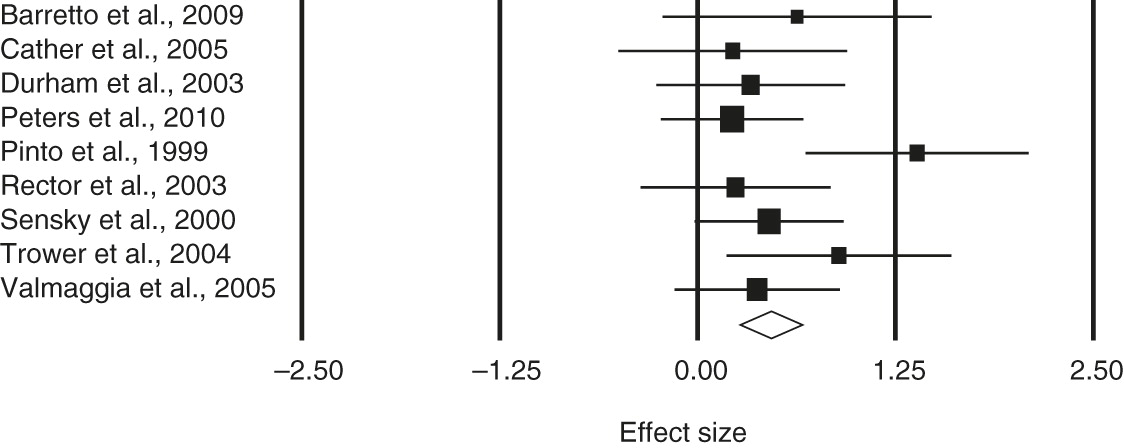

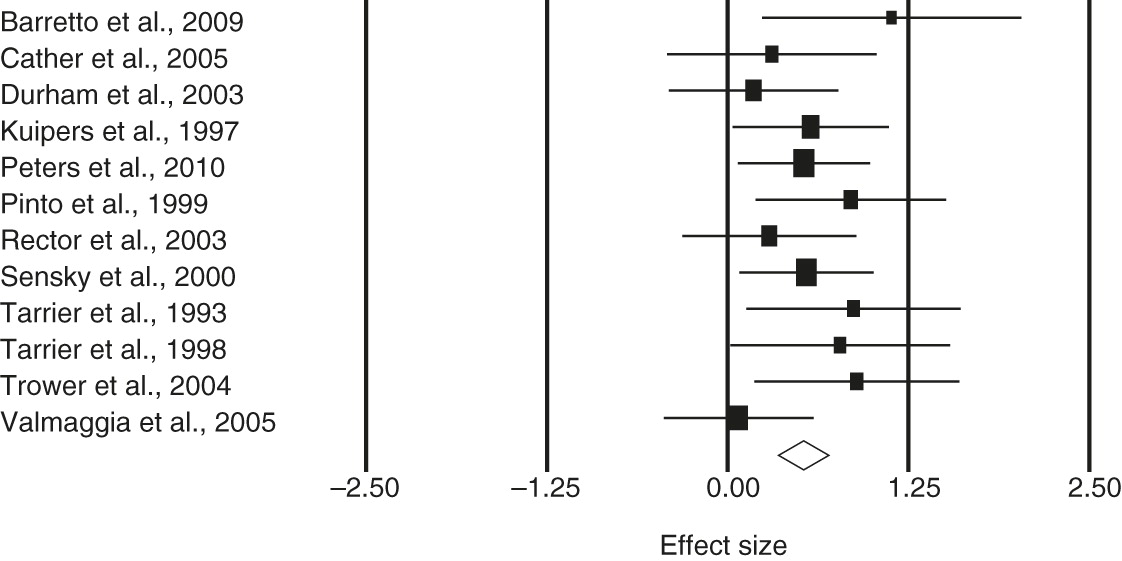

Effect sizes

The test of heterogeneity, Cochrane’s Q, was not statistically significant, and thus a fixed-effects model was assumed. Positive symptoms at posttreatment and at follow-up were examined. When general symptoms were reported, a separate analysis was undertaken. For positive symptoms, the estimated effect size at posttreatment was .47 (95% confidence interval [CI]=.27–.67); the corresponding effect size at follow-up was .41 (CI=.20–.61). For general symptoms, the estimated effect size at posttreatment was .52 (CI=.35–.70); the corresponding effect size at follow-up was .40 (CI=.20–.60).

Table 2 presents the estimated overall effect size, the CI, the test of heterogeneity of the effects, the number of studies, and the total sample size. Forest plots of the effect sizes and associated 95% CIs for positive and general symptoms are shown in

Figure 1 and

2, respectively.

Simple and relative efficacy was examined by comparing CBT to treatment as usual and an active control condition. When the effect size of CBT was compared with treatment as usual for positive symptoms, there was no statistically significant change. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference for general symptoms when CBT was compared with treatment as usual or active control. Therefore, the type of control used does not appear to influence effect size in this patient population.

Trial quality

A comparison of trials with blind and with nonblind assessment showed a statistically significant homogeneity statistic for the nonblind assessment in the analysis of positive symptoms (Q

1=7.55, p<.01), indicating that the effect sizes within this subgroup differed more than would be expected from sampling error alone. However, there were only two studies in this analysis (

56,

57), and the statistical power of the Q statistic depends on the number of included studies (

67).

For both positive and general symptoms, nonblind assessment yielded higher estimates of effect sizes than did blind assessment. For positive symptoms, the estimated effect size for blind assessment was .43 (CI=.20–.67), and the corresponding figure for nonblind assessment was .56 (CI=.18–.95). For general symptoms, the estimated effect size for blind assessment was .44 (CI=.22–.67), and the corresponding figure for nonblind assessment was .65 (CI=.37–.94). The differences between blind and nonblind assessment, a measure of trial quality, were not statistically significant for either positive or general symptoms.

Publication bias

Possible publication bias was examined by a funnel plot (treatment effect size against standard error). An inspection of the funnel plot indicated that the studies were distributed symmetrically about the combined effect size, indicating the absence of publication bias. The fail-safe N indicated that 98 null studies would need to be included to nullify the effects of the current meta-analysis.

Discussion

CBT for psychosis was originally developed for outpatients with medication-resistant positive symptoms, and a majority of studies have assessed patients with this common clinical presentation. Yet previous meta-analyses have not provided an estimate of effect sizes of CBT specifically for these patients. This meta-analysis identified 16 published articles from 12 randomized controlled trials that recruited patients with positive symptoms and explicitly measured changes in these symptoms in response to treatment. The results of this meta-analysis indicate an overall mean weighted effect size for positive symptoms of .47, indicating a medium effect size on completion of treatment. The effect size was maintained at follow-up assessment, with a mean weighted effect size of .41. The robustness of the effect size was maintained regardless of whether the trial included raters blind to the treatment condition. In addition, the type of control group used (treatment as usual versus active treatment) did not appear to influence effect sizes. This finding is similar to that of a recent meta-analysis by Sarin and colleagues (

41), whereby the type of control group (treatment as usual versus other psychological treatments) did not produce significantly different effect sizes.

Although our focus on a common subset of patients at one stage in their treatment serves to diminish the heterogeneity in the literature, limitations of this review nonetheless remain. The most salient limitation was the aggregation of various methods and models of CBT within a common category for analysis. Aggregation across various adjunctive control therapies may also have undermined delineation between more or less effective alternate strategies. Another important issue is the identification of the active ingredients. For example, CBT for psychosis refers to a range of CBT components that vary in length and emphasis. At least four treatment manuals for CBT for psychosis have been empirically validated in randomized controlled trials. Thus this review—and the field as a whole—has not identified the active elements in CBT protocols. Moreover, questions of relative efficacy, where adjunctive CBT has been compared with other, less specific psychotherapies, have been addressed (

50), but clear conclusions cannot be drawn.

Another limitation of the review is that many of the studies included were carried out by or under the supervision of experts in CBT for psychosis (

29). In most cases, the supervising therapists wrote the treatment manuals. The results of the studies are thus limited to well-trained and experienced psychologists with expertise in CBT for psychosis and may not generalize to experienced general mental health clinicians.

Conclusions

The evidence to date supports the assertion that CBT is effective in the management of persistent positive and general symptoms in medication-resistant psychosis. This review suggests that patients with medication-resistant positive symptoms may derive more benefit from an adjunctive psychotherapy, such as CBT, than from adjunctive medications.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The authors report no competing interests.