Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most common mental disorders among veterans returning from recent deployments (

1–

3). Yet, despite the availability of evidence-based treatments, there are multiple barriers to initiating mental health treatment (

1–

4). Many military personnel and veterans who report barriers to mental health care do not seek treatment or postpone seeking it (

4,

5).

Among veterans who do seek mental health care, the time lag is quite significant (

6). In a previous study, we found that recently returning veterans with psychiatric diagnoses had delayed initiating mental health care at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) by a median of over two years after their last deployment ended (

6). Delays in care can translate into delays in symptom and functional improvement, hindering readjustment to civilian life, family, and community.

Some studies have examined predictors of PTSD symptom worsening, but outside of randomized treatment trials, only a few studies have examined variables that are associated with PTSD symptom improvement. In other words, few studies have examined variables that are associated with PTSD symptom improvement in a naturalistic fashion, by allowing treatment initiation or engagement to vary among participants (

7,

8). Furthermore, even fewer studies have examined these questions among military personnel or veterans, particularly among those who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Existing studies have found a few variables that were associated with PTSD symptom improvement. For example, service members serving in multiple deployments demonstrated greater symptom improvement than those serving in a single deployment (

7). For other demographic variables, the association with improvement is unclear. For example, although we know that female gender may be associated with the development of PTSD (

9), it is not clear how gender is related to PTSD symptom improvement.

If we can better understand why some individuals improve, we can better understand the course and trajectories of PTSD and how to best contribute to individuals’ recovery. This study evaluated demographic, military, temporal, and logistic variables that may be associated with PTSD symptom improvement. We were particularly interested in whether seeking mental health treatment sooner was associated with improvement in PTSD symptoms.

Methods

Data source and extraction

We conducted a retrospective analysis of existing medical records from the VA’s Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF)/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)/Operation New Dawn (OND) roster, a national database of veterans who have separated from OEF/OIF/OND military service and who have enrolled in VA health care. Veterans of OEF served predominantly in Afghanistan, and veterans of OIF and OND served predominantly in Iraq. We linked the OEF/OIF/OND roster database, which contains veterans’ demographic and military service information, to the Decision Support System’s National Data Extract of pharmacy data and the VA National Patient Care Database, which provides VA visit dates and associated diagnostic codes from the

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). These data are derived from electronic medical records generated during clinical visits. Visits to mental health outpatient and primary care services are categorized by clinic stop codes (

10). Mental health outpatient services include visits to integrated care clinics providing primary care and mental health care (

11,

12). Fee basis codes designate care that is rendered at non-VA facilities and reimbursed by the VA but do not capture all non-VA care, such as care reimbursed by private insurance. The results of PTSD screening were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

All analyses were restricted to OEF/OIF/OND veterans who had received a diagnosis of PTSD (ICD-9-CM code 309.81) during two or more clinical encounters that occurred after the end of their last deployment and before December 31, 2012; had utilized mental health outpatient care between October 1, 2007 (beginning of nationwide primary care screenings), and December 31, 2012, and had not made any prior use of VA care; and had received PTSD screenings at both the start of treatment (up to three months before and one month after the first mental health visit) and on at least one other occasion occurring at least one year later (N=39,690). Of veterans who newly entered mental health treatment, 83% had a baseline screen for PTSD, and of those with a baseline screen, 50% had a follow-up screen during the period beginning one year later. The follow-up screen that was closest in proximity to the one-year follow-up date was utilized.

Measures

PTSD symptoms were assessed by using the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) (

13,

14), the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (

15,

16), or both. Both measures were included in order to capture the most representative sample, given that the PC-PTSD screen is mainly used in VA primary care settings and other non–mental health settings and the PCL is used primarily in VA mental health settings. The PC-PTSD, a brief four-item screen given annually and after each deployment, is designed to detect possible PTSD symptoms (

17). The screen yields binary responses (yes or no) for each of four PTSD symptom clusters: reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal; a score of ≥3 designates a positive PTSD screen for veterans.

The PCL is a 17-item measure, with each item rating the presence of a different symptom over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale, from not at all to a little bit, moderately, quite a bit, and extremely. The PCL has been shown to have very good internal consistency, and it correlates strongly with other measures of PTSD symptoms (

16). The PCL also demonstrates high diagnostic efficiency (.90) (

15). Within the VA, the PCL is mainly administered at the discretion of treating clinicians, typically to track patient progress during the course of mental health treatment. For the purposes of this study, symptoms rated as moderately or above on the PCL were considered present. PTSD symptoms from the PCL were combined in order to create indicators that paralleled each of the four symptom cluster proxies from the PC-PTSD (

18) The validity of the mapping of PCL questions onto PC-PTSD items was tested by examining concordance between the two screens given at the VA on the same date. For the purposes of validation, all OEF/OIF/OND veterans who were administered the PCL and the PC-PTSD on the same date (not restricted to our study sample) were included (N=53,756), with a total of 57,889 instances in which a given veteran had both a PC-PTSD and PCL administered on the same day. [A table describing the mapping of the PCL to the PC-PTSD and agreement between the two instruments is available online as a

data supplement to this article.]

We created a composite variable, referred to as the PTSD screen result; endorsing three or more symptoms on either measure constituted a positive screen for PTSD (

14,

19).

Dependent variable

The binary dependent variable, a negative (versus positive) PTSD screen result, was defined as a score of <3 at follow-up on the PTSD screen. This outcome comprised PTSD screen results that had improved or had remained negative compared with baseline results (versus having worsened or remained positive).

Independent variables

The main independent variable was time until initiation of mental health outpatient treatment, which was defined for each person as the time (in years) from the end of the last deployment until the first mental health outpatient visit. Other independent variables included date of birth, gender, race-ethnicity, marital status, and military characteristics. Details about each person’s military characteristics (armed forces branch [Army, Marines, Navy or Coast Guard, or Air Force], rank, component type [National Guard and reserves or active duty], and number of deployments [one or multiple deployments]) were extracted from the OEF/OIF/OND roster. Information about the type of VA facility nearest to the individual and the distance to the closest facility was derived from the OEF/OIF/OND roster by the VA planning and system support group.

The following independent variables were treated as potential confounders because each could account for change in PTSD symptoms: mental health outpatient treatment utilization, defined as the number of mental health clinic visits between the start of mental health treatment and the follow-up screen; regular use of primary care services, defined as a mean interval between visits of six months or fewer; and use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for 12 consecutive weeks or more, as encoded in VA outpatient pharmacy data.

Analysis

We used logistic regression analysis to examine the association of independent predictor variables with a negative PTSD screen result. In separate logistic regression models, we examined predictors of PTSD screen results for each of the four PTSD symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal). The main predictors of interest included time from the end of the last deployment to initiation of mental health outpatient treatment, gender, age, race-ethnicity, marital status, military component, rank, branch, number of deployments, and distance to and type of nearest VA facility. The multivariable analysis adjusted for potential confounders of the association between changes in PTSD symptoms and predictors. Potential confounders included baseline PTSD screen result, timing of follow-up screen, regular utilization of primary care services, total mental health outpatient treatment utilization, and SSRI use. Primary care and mental health service utilization and antidepressant use were included only for adjustment purposes because of potential biases due to confounding by indication. More specifically, persons who are more symptomatic are more likely to utilize health services and antidepressant medications.

We tested interactions of demographic and military predictors with each other and, separately, with time to initiation of mental health outpatient treatment. As mentioned above, the study combined results for veterans whose PTSD screen result had improved from baseline with those for veterans whose screen result had remained negative. To determine whether it was valid to combine these scores, we tested interactions of baseline screen results with demographic and military factors and, separately, with time from the end of the last deployment to initiation of mental health outpatient treatment. All tests were two-tailed. Analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.3 (

20). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Results

The sample was 90% male, with a mean±SD age of 30.5±8.16; 57% were white, 11% were black, 11% were Hispanic, and 21% were of other or unknown race-ethnicity. At the time of initiation of mental health outpatient treatment, 75% of the veterans screened positive for PTSD, having endorsed at least three of the four PTSD symptom clusters on the PTSD screen (

Table 1). After at least one year (mean follow-up=2.37±.93 years), 27% (N=7,908) of those with a positive screen at baseline had improved, and 43% (N=4,329) of those with a negative screen at baseline continued to screen negative.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the following characteristics were associated with a negative PTSD screen result: women compared with men, older versus younger age at first mental health outpatient visit, officer rank compared with enlisted rank, service in branches of the military other than the Army, and negative PTSD screen at baseline (

Table 2).

Blacks were less likely than whites to have a negative screen result (

Table 2), and this difference persisted after adjustment for time from the end of the last deployment to mental health outpatient treatment. Similar to findings of previous studies, the median interval between the end of the last deployment and the use of services was about three months longer for blacks than for whites (p<.001, data not shown). The reduced likelihood among blacks versus whites of a negative PTSD screen result was partly driven by the 7% greater probability that blacks would screen positive for PTSD at follow-up after having screened negative at baseline (p<.001; results not shown).

Veterans who were married were slightly less likely than those who were never married to have a negative PTSD screen result. Veterans who lived more than ten miles away from the nearest VA facility were less likely than veterans who lived closer to have a negative screen result. Veterans who lived closer to a community-based outpatient clinic than to a VA medical center were also less likely to have a negative screen result.

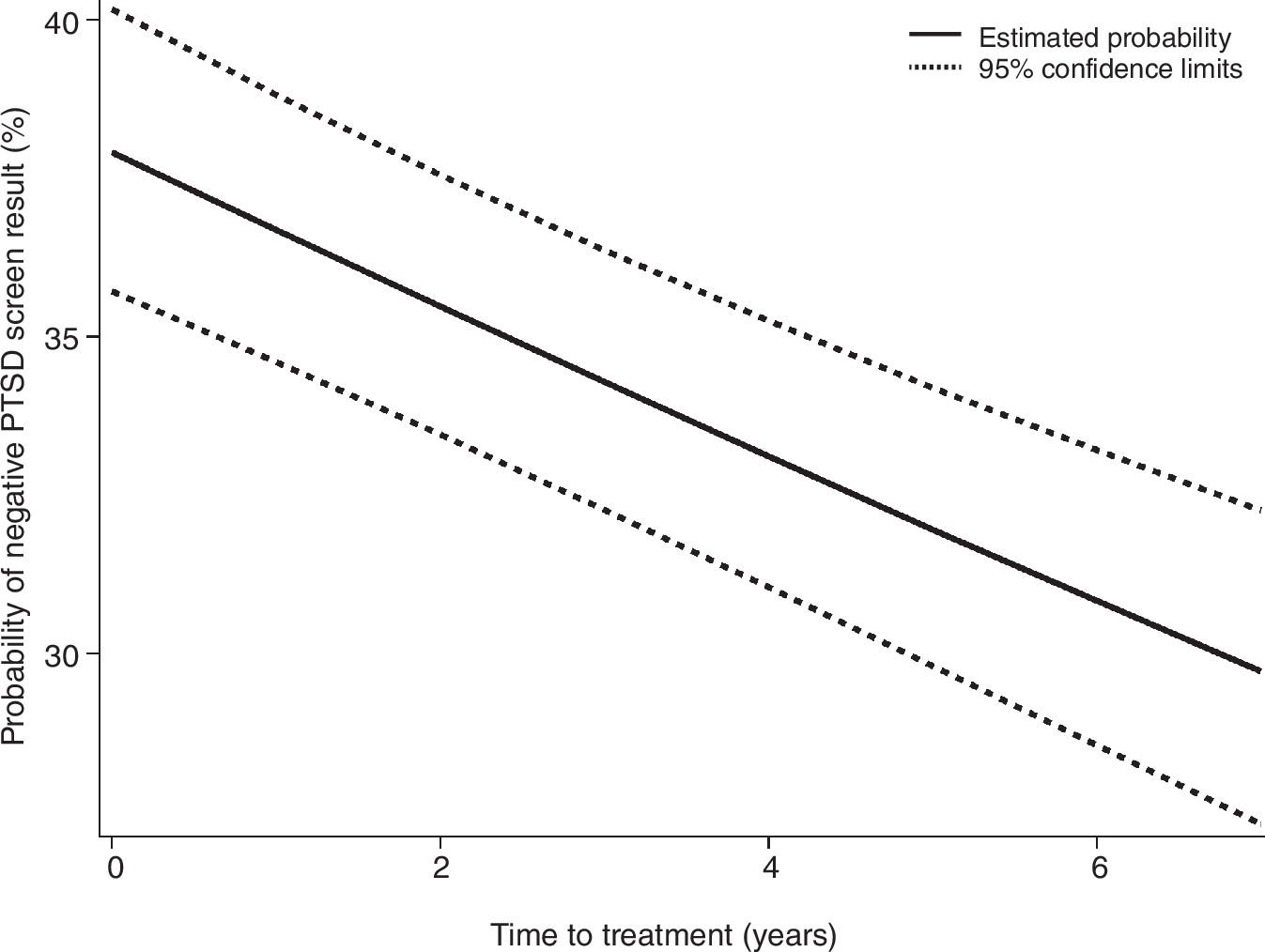

Notably, veterans who waited longer to initiate mental health outpatient treatment were less likely to have a negative screen result.

Figure 1 illustrates the decreasing probability of a negative screen result with each year that passed after the end of the last deployment.

Logistic regression analyses found similar patterns of association between predictor variables and PTSD screen results for each of the four PTSD symptom clusters (results not shown).

Discussion

A number of demographic, military, temporal, and logistic variables were associated with symptom improvement or with continuing to score below the threshold for a positive PTSD screen. Although temporal variables are rarely examined, we found that greater time to mental health outpatient treatment engagement was negatively associated with PTSD symptom improvement. More specifically, veterans who waited longer to get mental health treatment were less likely than veterans who sought treatment sooner to experience PTSD symptom improvement during the study period. This finding sheds light on the importance of continuing to better understand barriers to mental health treatment, particularly given that less than half of veterans with mental health problems seek care and those who seek care do so after significant delays (

6,

21,

22).

Outreach efforts to help veterans engage in treatment in a timely manner are critical and may, in turn, help with PTSD symptom improvement over time. Intervening early when mental health problems are first detected should be a priority. Given that integrated primary and mental health care is now becoming available at many VA health care facilities, this “one-stop shop” model provides an optimal way to decrease time to seeking mental health care. Veterans in primary care who screen positive for any mental health problems can receive immediate mental health assistance within an integrated care model, which may assist with the stigma of receiving care in a mental health setting (

23). Indeed, veterans who received integrated primary care were more likely to receive a mental health evaluation or care within a month (

24).

We also found that female gender was associated with greater PTSD symptom improvement compared with male gender. Although civilian studies found that females are at greater risk of PTSD (

25), findings in military samples have been mixed, with some studies finding no gender differences (

26,

27). In addition, we recently found that although both genders experienced a delay in engaging in minimally adequate mental health care (eight mental health outpatient visits within a year), female veterans received minimally adequate mental health care about two years sooner than male veterans, which may explain why they achieved greater symptom improvement (

6).

Black veterans were less likely, but only modestly so, to demonstrate PTSD symptom improvement, compared with their white counterparts, and this difference was not explained by longer time from the end of the last deployment to mental health outpatient treatment initiation. That is not surprising, given that studies have consistently found that unmet treatment needs are greatest in underserved groups, including racial-ethnic minority groups (

28). It may be that veterans from racial-ethnic minority groups face particular barriers to treatment that are important to acknowledge, and more research is needed in this area in order to optimize outcomes. Furthermore, other variables, such as differential rates of traumatic stressors and preexisting conditions, are important to further explore and may explain some of these differences (

29).

Officers were more likely than enlisted personnel to experience PTSD symptom improvement. One possible explanation is that officer status may be a proxy for higher education; research has shown that lower levels of education are associated with chronic trajectories of PTSD (

30). However, other variables that we were not able to measure, such as social support in the aftermath of trauma (

31), may also explain some of these findings.

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, this study was conducted with a population of treatment-seeking veterans who had at least one visit to a VA health care facility. Therefore, our results should not be generalized to all OEF/OIF/OND military personnel or veterans. Second, we selected a population of veterans who served in support of OEF/OIF/OND, and, therefore, these results should not be generalized to veterans of other eras or to veterans from other countries. Third, ICD-9-CM diagnoses were acquired from administrative health records and were not verified with standardized diagnostic measures. A related concern is the combined use of two separate validated tools, the PCL and the PC-PTSD. We used both the PCL and the PC-PTSD in order to obtain the most representative sample and because they are the measures used by the VA system. Furthermore, we found that the method we used was statistically reliable. Nonetheless, combining two separate validated tools may have resulted in variations in these data. Future studies should continue to examine the validity and reliability of this method.

Fourth, because of the ways in which data appear in the VA administrative database, we were not able to distinguish between the types of mental health treatments that veterans were receiving, such as evidence-based treatment for PTSD or other mental health problems versus supportive therapy; rather, we could account only for number of visits. We hope to have better indicators of evidence-based treatment for PTSD in the future so that the particular types of care that veterans receive can be examined more closely in relation to symptom improvement. Fifth, because we used administrative data, we were not able to examine third variables that may be associated with our outcome, including severe avoidance symptoms, interpersonal difficulties, and poor attachment, among others. Finally, we were able to include only veterans whose PTSD symptoms were measured during at least two occasions; those who dropped out after one visit are not as well represented.

Conclusions

Veterans who waited longer to get mental health treatment were less likely to experience PTSD symptom improvement during the study period. Furthermore, improving barriers for black, male, younger, rural, lower-ranking, and possibly less well educated veterans is an important priority, given our findings. Models that integrate primary care and mental health care may be an optimal way to help expedite veteran treatment engagement.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by VA Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) Career Development Award (RCD 06-042) to Dr. Maguen, an HSR&D Service Directed Research Award (SDR-08-408) to Dr. Seal, and a Department of Defense Mental Health Research Infrastructure Award (W81XWH-11-2-0189) to Dr. Neylan. The authors thank Julie Dinh, B.A., for assistance.

Dr. Neylan has received study medication for a study funded by the Department of Defense and study medication for a study funded by the VA. The other authors report no competing interests.