Shared decision making is a collaborative process by which consumers and clinicians share information, provide expertise, and clarify preferences in order to reach agreement and make decisions regarding care and treatment (

1). Research has shown that there are both benefits (

2,

3) and perceived obstacles (

4) to utilizing a shared decision–making approach in medical encounters, and thus not all individuals may want the same level of involvement in their treatment. Preferences for shared decision making may differ across individuals, ranging from a preference to remain completely autonomous to a preference for sole reliance on one’s provider; preferences may also differ across various elements of decision making, such as how one obtains information, shares opinions about options, and makes final decisions (

5).

An understanding of shared decision–making preferences is particularly relevant in mental health care because there is an increasing focus on providing recovery-oriented, client-centered services (

1,

6–

8). However, because studies of shared decision making have largely focused on one-time decisions involving acute medical care, less is known about preferences for shared decision making among individuals with chronic conditions, including serious mental illness (

9). Further, much of the research on shared decision making in this population (

10–

12) is limited by small sample sizes and the use of the decision-making subscale of the Autonomy Preference Index (

13), which reduces shared decision making to a unitary construct.

Therefore, this exploratory study of an outpatient sample of veterans with serious mental illness aimed to evaluate three components of shared decision–making preferences with respect to mental health treatment and identify whether these components of shared decision–making preferences are associated with demographic factors, psychiatric diagnosis, type of prescriber, psychiatric symptom severity, or therapeutic relationship.

Methods

Data were drawn from a randomized controlled trial examining a computerized intervention that assisted veterans with serious mental illness in receiving recommended monitoring for the metabolic side effects of second-generation antipsychotic medications. Between March 2010 and October 2011, participants were recruited from two Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) outpatient mental health clinics in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic region. Potential participants were between age 18 and 70; had a chart diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified), bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); were prescribed one or more oral or injectable second-generation antipsychotic medications; had at least two outpatient visits with the prescribing provider (psychiatrist or nurse practitioner) in the past year; were deemed by the prescriber to be clinically stable to participate in the study; and had at least a fourth-grade reading level. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland School of Medicine approved the study, and all participants (N=239) provided written informed consent after receiving a complete study description.

The following self-report questionnaires were completed at baseline before the start of the intervention. Participants provided information on demographic variables, including age, sex, race, marital status, school or college enrollment status, work status, and education level. To assess preferences for shared decision making, we used the three items developed by Levinson and colleagues (

5) and adapted them to reference mental health treatment specifically. Items were rated on a 6-point scale from 1, strongly agree, to 6, strongly disagree. Items assessed preferences related to knowledge (“I prefer to rely on my psychiatrist’s/nurse practitioner’s knowledge and not try to find out about my mental illness on my own”; higher scores indicate a stronger preference for obtaining information on one’s own), options (“I prefer that my psychiatrist/nurse practitioner offers me choices and asks my opinion about treatments for my mental illness”; reverse-coded such that higher scores reflect a stronger preference for being offered options about treatments for mental illness), and decisions (“I prefer to leave decisions about my mental health care up to my psychiatrist/nurse practitioner”; higher scores indicate a stronger preference for making one’s own decisions about care). Psychiatric symptom severity over the past week was measured as the overall average score (range 0–4) on the 24-item self-report revised Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24) (

14). The quality of the therapeutic relationship was assessed with the 12-item patient-report Scale To Assess the Therapeutic Relationship (STAR-P; range=0–48) (

15).

We used univariable statistics to describe participants’ responses to the three shared decision–making questions. We then conducted a multivariable linear regression to determine the associations between the shared decision–making preferences and demographic variables, psychiatric diagnosis, prescriber type (psychiatrist or nurse practitioner), psychiatric symptom severity (BASIS-24), and therapeutic relationship (STAR-P). The 6-point Likert scale responses for shared decision–making preferences were treated as continuous scores for multivariable regression analyses.

Results

Most of the 239 participants were male (N=213, 89%); the mean±SD age was 54.3±8.3. The sample was racially diverse: 47% white (N=113), 47% black (N=113), 4% multiracial (N=9), 1% American Indian or Alaska Native (N=3), and <1% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (N=1). Twenty-six percent (N=61) of participants were currently married, 56% (N=134) had at least some college education, 20% (N=49) were working for pay, and 8% (N=19) were enrolled in school or college. Thirty percent (N=72) had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, 32% (N=76) had bipolar disorder, 26% (N=63) had major depressive disorder, and 12% (N=28) had PTSD. In general, the sample reported low levels of psychiatric symptomatology, as indicated by the BASIS-24 overall mean score of 1.3±.73. The STAR-P total score was 40.1±6.6, which reflected a moderately strong therapeutic relationship.

All 21 prescribers of second-generation antipsychotics in the outpatient mental health clinic who were asked to participate in the study agreed; of these, 62% (N=13) were psychiatrists, and 38% (N=8) were psychiatric nurse practitioners.

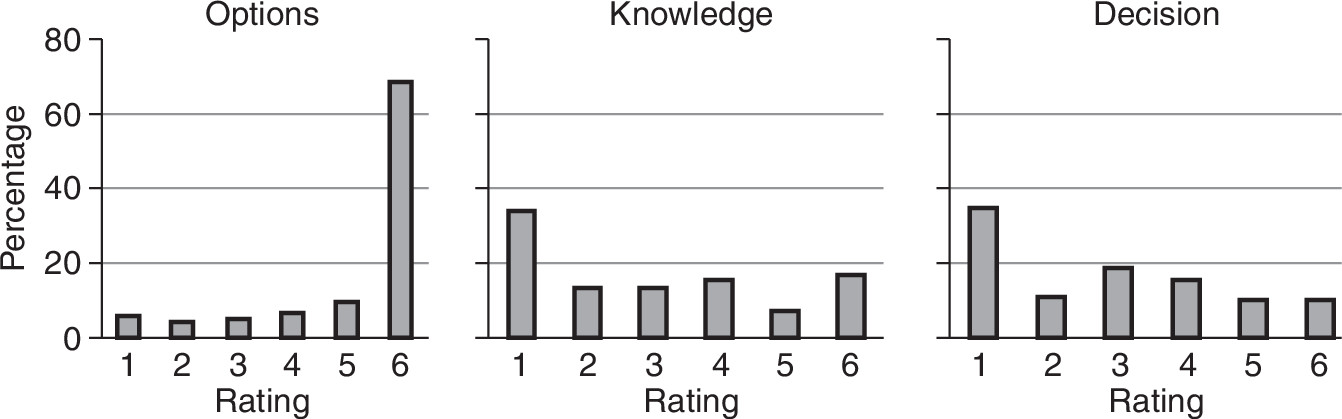

Frequency distributions for the options, knowledge, and decision questions are provided in

Figure 1. There was little variability when participants were asked whether they preferred to be offered choices and to be asked their opinions about their mental health treatment by their providers: 85% (N=203) were in agreement (responses 4–6 [reverse coded]). Therefore, no further analyses were conducted with the options variable. Sixty-one percent (N=145) were in agreement (responses 1–3) with preferring to rely on their providers’ knowledge rather than obtaining information about their mental illness on their own. In terms of preferences for participating in decision making, a similar percentage of participants (64%, N=154) were in agreement with preferring to have their mental health providers make the final decisions about their care (responses 1–3). The knowledge and decision variables were sufficiently variable for further analysis and were also positively correlated (

r=.54, p<.001).

Knowledge

Multivariable analyses demonstrated that race, employment, education, diagnosis, and therapeutic relationship predicted shared decision–making preferences regarding knowledge (

Table 1). White participants were more likely to prefer relying on their providers’ knowledge (β=–.86, p<.001), whereas those who worked for pay (β=.76, p=.007) and those with some college or higher education (β=.66, p=.004) were more likely to want to find out about their mental illness on their own. Compared with individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, those with major depressive disorder (β=.82, p=.01) or PTSD (β=.92, p=.03) were more likely to indicate a preference for obtaining information about their mental illness on their own. Veterans who reported having a stronger therapeutic relationship with their providers were more inclined to rely on their providers’ knowledge about their mental illness than to seek information on their own (β=–.06, p=.002).

Decision

Multivariable analyses demonstrated that education and therapeutic relationship predicted decision-making preferences. As with preferences for obtaining knowledge, participants with some college or higher education were more likely to want to make decisions on their own (β=.56, p=.01), whereas participants who reported having a stronger therapeutic relationship with their provider had a greater preference for leaving final decisions about mental health care to their providers (β=–.06, p<.001).

Discussion

This study evaluated three components of shared decision–making preferences with respect to mental health treatment among individuals with serious mental illness, including preferences for obtaining information, sharing opinions about treatment options, and participating in treatment decisions. First, our results indicate that being offered choices and being asked one’s opinion about treatments for mental illness were nearly universally preferred. This is consistent with previous research (

5) and suggests that offering options is a component of shared decision making that should always be present and incorporated into mental health care.

However, in terms of obtaining knowledge about mental illness and making final decisions about mental health care, veterans reported greater variability in preferences, along the continuum of provider directed to patient directed. As for individuals receiving treatment in a general medical context (

5), these data indicate that not all individuals with serious mental illness desire the same level of participation in their mental health care. A shared decision–making approach may be a novel concept to many mental health consumers, which may require clinicians to educate consumers about taking an active role in their recovery (

16); this would in turn empower consumers to move beyond the passive stance that they may have internalized during earlier periods of paternalistic care. Further, an individual’s participation preferences may vary depending on the specific component of shared decision making, and these preferences should be explicitly assessed (

17). In fact, recent research examining clinical interactions during actual psychiatric visits found that active discussion of consumer preference was the only significant predictor of final agreement between consumers and providers (

16), which highlights the clinical utility of thoroughly assessing and discussing participation preferences.

In examining factors that may affect shared decision–making preferences, we found that white participants were more likely to rely on their providers’ knowledge for information about their mental illness, which may be related to different patterns of help seeking or greater mistrust of the mental health system among African Americans (

18). However, 19 of the 21 prescribers in our study were white, and this finding may also be explained by greater race concordance between white patients and their prescribers, which we were unable to adequately investigate for patients from minority racial groups. Further, although severity of psychiatric symptoms was not associated with participation preferences, our results demonstrated that psychiatric diagnosis may moderate preferences for obtaining information about one’s mental illness. Individuals with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder were more likely to prefer relying on their providers’ knowledge instead of obtaining information on their own.

We also found that individuals who indicated having a stronger therapeutic relationship with their prescriber, regardless of whether the prescriber was a psychiatrist or nurse practitioner, were more likely to prefer relying on their providers’ knowledge and leaving final decisions about mental health care up to their providers. Factors such as trust and understanding, which help inform the strength of a therapeutic relationship, may also play a role in an individual’s preferring to rely on his or her provider for knowledge and decision making. Thus, because an individual’s shared decision–making preferences may change over time, clinicians should periodically reevaluate such preferences as the working relationship evolves.

This study had several limitations. The sample consisted primarily of older males. In addition, the study asked participants to report preferences for shared decision making with the prescriber of their second-generation antipsychotic. Participation preferences for other types of treatments or with nonprescribing mental health providers were not evaluated. Further, data on the length of time that individuals had been seeing the particular provider were not available and thus could not be included as a predictor in analyses. The assessment of participation preferences used in this study has not been validated in a psychiatric population. In addition, the measure of shared decision–making preferences ranged from completely patient directed to solely provider directed; the degree to which self-reported preferences correspond to actual shared decision–making behavior in general medical or mental health encounters is unclear, and future research should further examine this relationship. Finally, this study was exploratory in nature, and replication is necessary to confirm findings.

Conclusions

Shared decision making in mental health treatment is likely a multifaceted construct, including—but not limited to—preferences for seeking knowledge, sharing opinions about treatment options, and making final decisions. Although increasing consumer involvement is often considered a hallmark of recovery-oriented mental health care, more shared participation may not always be better if it is not aligned with patients’ preferences. Therefore, repeated evaluation over time of preferences in regard to shared decision making may be the preferred and more client-centered approach.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by a VA Health Services Research and Development Merit Award (IIR-07-256); by the VA Capitol Health Care Network (VISN 5) Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center; and the VA Maryland Health Care System/University of Maryland School of Medicine Psychology Internship Consortium. The contents do not necessarily represent the views of the VA or of the U.S. government.

The authors report no competing interests.