In 2010, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death in the United States (

1). Although preventing suicide is a complicated problem, the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention asserts that suicide is indeed preventable (

2). In 2012, the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention made suicide a top public health priority, setting the goal to save 20,000 lives in the next five years (

2). To achieve this goal, the strategy called for the development of an agenda prioritizing research on individuals at increased risk of suicide. Members of the Armed Forces and veterans were among 11 high-risk populations of interest named in this call to action.

An increase in suicide among active military personnel has been documented (

3,

4). Further research is needed, however, to better understand the distribution of suicide risk among veterans after active-duty service and to understand population-based differences between those with and without a history of military service, after accounting for key demographic differences (

5–

7). The demographic composition of the veteran population is changing as the proportions of younger, female, and nonwhite veterans increase (

8). There are also early indicators of changes in the prevalence of service-related injuries, such as traumatic brain injury (

9), and exposures, such as military sexual trauma (

10), that may precipitate changes in suicide risk among post–9/11 veterans (

11,

12). A more complete picture of the absolute and relative risk of suicide for all veterans and within meaningful subgroups is necessary to appropriately target and evaluate treatment and prevention programs, allocate suicide prevention resources, and track changes in suicide rates over time.

A small number of studies limited to veterans who used services provided by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) observed a 42% to 66% increase between 2000 and 2007 in relative risk of suicide compared with the general U.S. population (

13,

14), but these studies were unable to determine the absolute or relative mortality for veterans not using VHA services. Little is known about differences in suicide rates between veterans who use VHA services and those who do not. One study estimated a 50% increased risk among male veterans using VHA services (

15). Although these findings are important, they may not be generalizable to the broader veteran population.

Thus, as an initial step toward improving our understanding of suicide risk among veterans, this study aimed to characterize veteran suicide risk compared with risk among nonveterans, characterize differences in relative suicide risk between veterans with and without a history of VHA service use, and examine the role gender plays in these differences.

Results

Of the 173,969 suicide decedents included in the data, 25% were veterans; 20% did not have a history of VHA service use, and 5% were VHA-utilizing veterans. Veteran suicide decedents were older than nonveteran suicide decedents, and a larger proportion was male. From 2000 to 2010, the proportion of veteran suicide decedents with a recent history of VHA service use increased marginally (17% to 19%), and the proportion of all veterans using VHA services nearly doubled (from 14% to 25%) (

Table 1). Due primarily to an influx of younger veterans and an increase in VHA service use among veterans over age 60, the number of VHA-utilizing veterans increased by approximately one million during the study period despite a decrease in the overall veteran population of nearly two million.

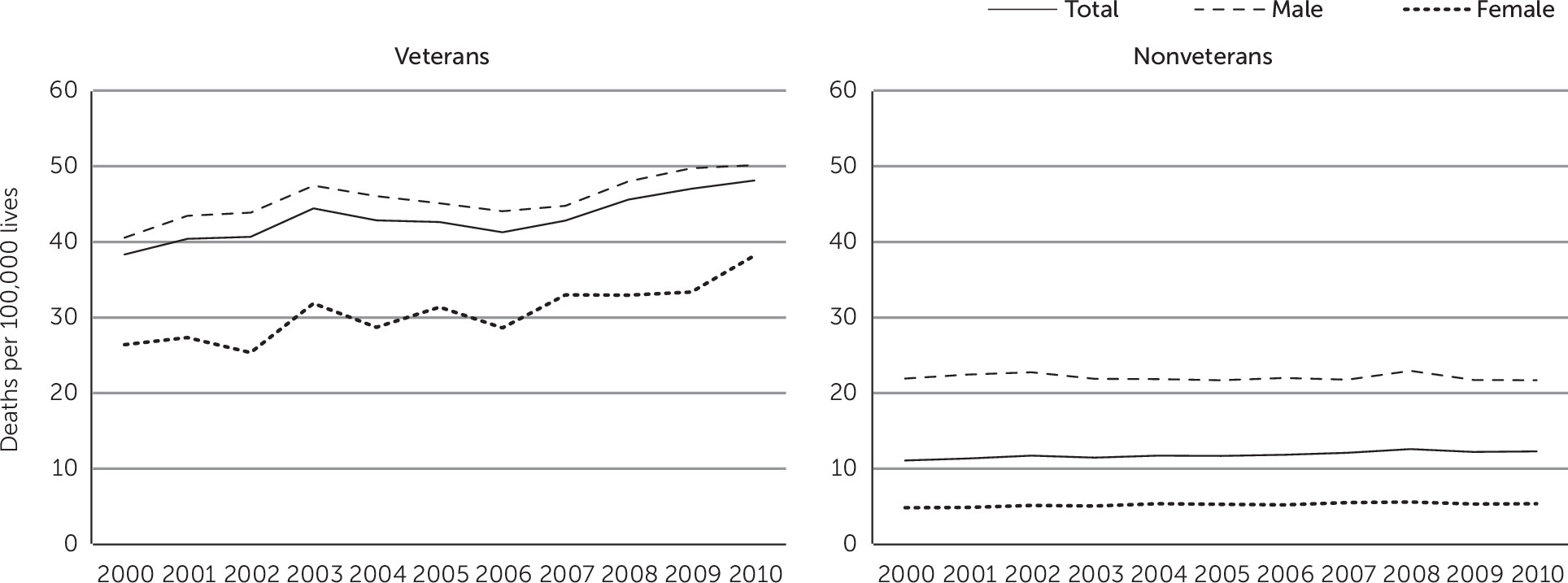

From 2000 to 2010, both the crude and age-adjusted veteran suicide rates increased by approximately 25% while the comparable nonveteran rates increased by approximately 12% (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). Of note, a 13% increase was observed for nonveteran females (4.8 to 5.4 per 100,000 lives) while a 40% increase was observed for veteran females (24.7 to 34.6 per 100,000). Although VHA-utilizing veterans experienced a higher suicide rate in 2000 than non–VHA-utilizing veterans (34.5 versus 27.6 per 100,000), the suicide rate among VHA-utilizing veterans declined over the study period, and by 2010, the rate among VHA-utilizing veterans was lower than the rate among non–VHA-utilizing veterans (27.6 versus 38.7 per 100,000).

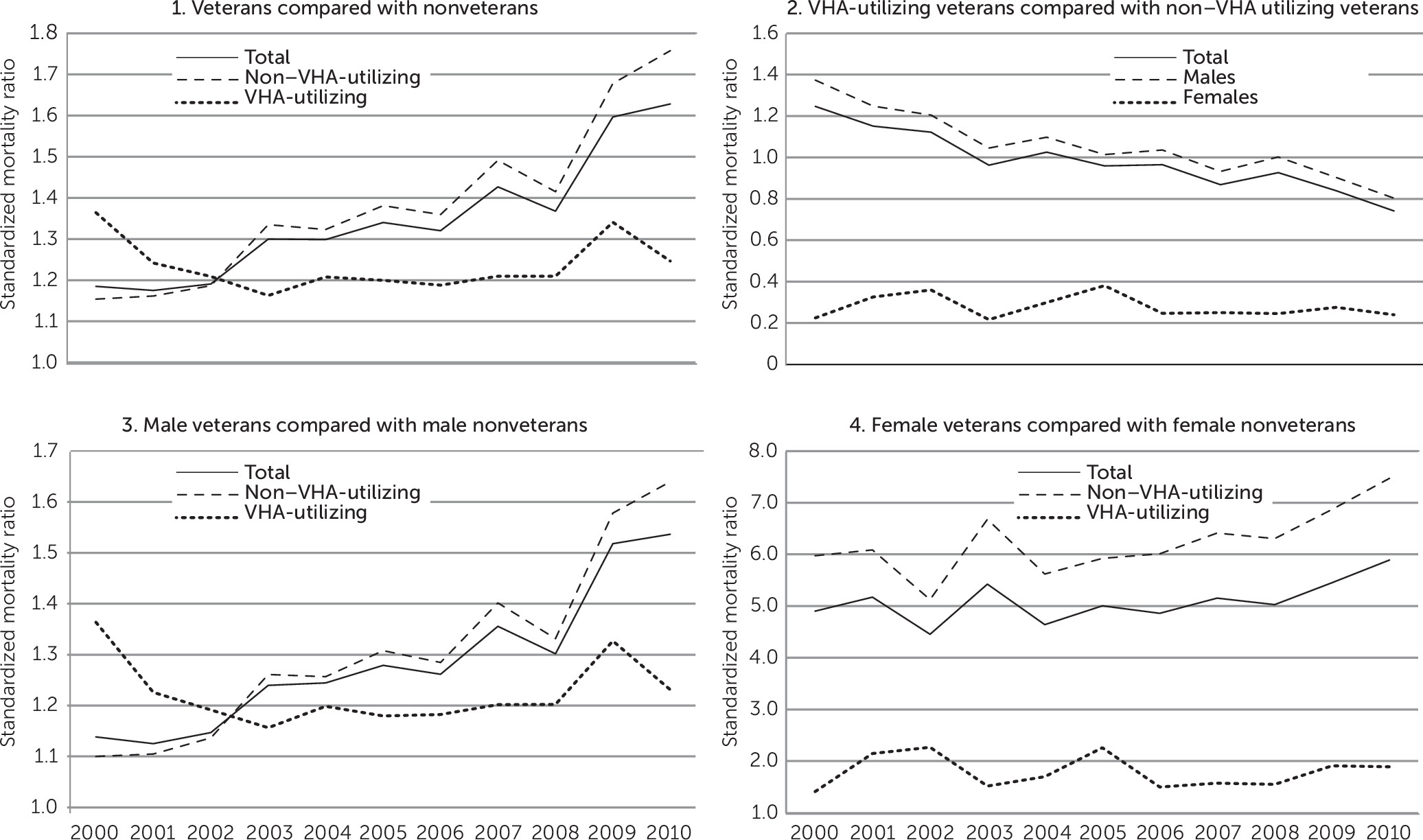

After accounting for age and gender differences using SMRs, the number of observed suicides among veterans was significantly higher than expected had suicide rates been the same as those observed for nonveterans. Specifically, in 2000 the number of observed veteran suicides was approximately 20% higher than expected, and the number increased to over 60% higher than expected in 2010. Findings for males followed the same pattern. Observed suicides among female veterans, however, were 390% higher than expected in 2000, increasing to nearly 490% higher than expected in 2010 (

Figure 2).

In addition to gender differences, meaningful differences emerged when VHA service utilization was examined. Although the magnitudes and time trends for non–VHA-utilizing veterans mirrored those of the veteran population as a whole, this was not the case for VHA-utilizing veterans (

Figure 2). In 2000, the age- and gender-adjusted SMR for VHA-utilizing veterans compared with nonveterans was greater than that for non–VHA-utilizing veterans, but it declined considerably over the next three years. From 2003 to 2010, SMRs for VHA-utilizing veterans compared directly with non–VHA-utilizing veterans were significantly less than 1 (

Figure 2), indicating that the observed number of suicides for VHA-utilizing veterans was less than expected had their suicide rates been the same as for non–VHA-utilizing veterans. The sensitivity analysis [see online

supplement] suggests that these SMRs provide conservative estimates of the relative risks of interest, which may be slightly higher.

Finally, considering gender and VHA service utilization simultaneously, the decline in SMRs among VHA veterans was primarily observed for males (

Figure 2). In 2000, male VHA-utilizing veterans experienced 36% more suicides than expected compared with their nonveteran peers; this declined to a low of 16% in 2003 and increased slightly to 23% by 2010. Conversely, no clear period of change emerged for female VHA-utilizing veterans, who experienced approximately one-and-a-half to two times the number of suicides expected compared with nonveteran females. Estimates for female VHA-utilizing veterans were less precise due to the small number of annual suicides in some age groups. When female VHA-utilizing veterans were compared directly with female non–VHA-utilizing veterans, however, SMRs were consistently and significantly less than 1, indicating that female VHA-utilizing veterans experienced fewer suicides than expected if their rates had been similar to veterans who did not use VHA services (

Figure 2 and online

supplement). Female veterans who did not use VHA services experienced the greatest number of excess suicides compared with their nonveteran peers throughout the study period (

Figure 2).

Discussion

Evidence of increasing suicide risk among select U.S. subgroups is mounting (

20). Most notably, significant increases have been observed among middle-aged men and women since 1999 (

21). The question of how veterans contribute to this change has received considerable attention in recent years (

5–

7). Prior SMR estimates using indirect estimation methods for VHA-utilizing veterans compared with the general population have been published (

13,

14). Suicide SMRs for VHA patients by fiscal year were previously reported to have decreased from 1.7 in 2000 to 1.4 in 2007 (

14). To the best of our knowledge, however, ours is the first study to directly compare veteran and nonveteran suicide risk using a validated variable for veteran status while documenting differences in suicide rates between veterans who were VHA service users and those who were not. On the basis of these analyses, veterans appear to be another select U.S. subpopulation experiencing greater than average increases in suicide rates. Importantly, however, such increases were not observed uniformly across the veteran population. Crude suicide rates declined among veterans using VHA services from 2000 to 2010, and, even after the analysis accounted for age and gender, the excess risk among VHA-utilizing veterans compared with their nonveteran peers decreased as well. Conversely, increases in suicide rates among veterans without a history of VHA service use were occurring alongside, and more rapidly than, increases among U.S. adults without a history of military service. It is reasonable to assert, therefore, that factors within the veteran population may make this group particularly susceptible to stressors and subsequent mental health conditions associated with increased risk of suicide (

22), which may be partially mitigated by use of VHA services.

Combat-related exposures have been suggested as one factor contributing to increases in veteran suicide risk compared with nonveterans; however, recent research indicates that this may not fully explain observed differences (

3). Alternatively, increased suicide risk among some veteran groups may be related to characteristics that are not unique to veterans but that may be associated with selection into military service. For example, adverse childhood experiences have been shown to increase the risk of a suicide attempt (

23) and may serve as motivating factors for selecting military service (

24)—essentially providing an escape route from suboptimal family environments. Additional research is needed on factors differentially associated with selection of U.S. military service that may explain differences in suicide risk. It is also possible that veterans are overrepresented in populations that are particularly vulnerable to stressors related to suicide, such as the recent economic downturn (

25), that affect the U.S. population as a whole. These may include marginally employed populations or those with greater economic vulnerability (

26) and homeless populations (

27).

Study findings clearly suggest that veterans without a history of VHA service use are at particularly high risk of suicide. However, it is likely that this group is quite heterogeneous, and national data on clinical characteristics and risk exposures are not readily available. Although some veterans who do not use VHA services may be healthy or may have private health insurance, others may choose not to use VHA services for reasons related to difficulties accessing care, misconceptions regarding quality of care, a lack of knowledge about eligibility for services, or perceived stigma surrounding seeking mental health care. Research is warranted to better understand suicide risk among veterans who do not use VHA services and whether characteristics related to VHA service eligibility and use are related to suicide risk.

In addition, despite overall improvements, clear gender differences emerged for veterans who used VHA services. SMRs for VHA-utilizing and non–VHA-utilizing female veterans were substantially higher than those observed for males. Although female veterans who used VHA services consistently experienced fewer suicides than expected relative to female veterans who did not use VHA services, there was no meaningful change in this estimate over time. Conversely, SMRs decreased over time among male VHA-utilizing veterans. Research on risk and protective factors unique to female veterans is needed.

Finally, although most of the decline in SMRs among VHA-utilizing veterans in this study occurred prior to the onset of activities in support of current VHA suicide prevention programs (

28), this does not suggest that prevention programs have been ineffective. Rather, the plateau observed among VHA-utilizing veterans from 2004 to 2009 occurred in contrast to a rising suicide rate among non–VHA-utilizing veterans. One possible reason for this relative stability could be that VA’s Mental Health Enhancement Initiative and Suicide Prevention Program are successfully countering rising veteran suicide rates. That said, gender differences discussed above suggest possible gender-based differences in the effectiveness of VA suicide prevention initiatives. There may also be differences in health and demographic factors among male and female veterans who use VHA services, or there may be a difference in baseline risk of suicide related to eligibility for or self-selection into VHA services that may vary by gender. These results further support continued efforts to better understand health disparities, including suicide, among women veterans and the most effective clinical and public health strategies to prevent suicide among this fastest-growing subgroup of veterans.

Although this study is a novel and important contribution to the literature, it had limitations. The data source was limited to suicides. Because information was not available on other causes of death, particularly undetermined causes and accidental overdoses, it was not possible to account for potential misclassification of suicides as other causes of death. Such misclassification likely differs by age and gender (

29). Misclassification may also differ by veteran status given that the availability of information to classify cause of death might vary by veteran status and veterans are more likely to use firearms for suicide, a mechanism that is less likely to lead to misclassification. At this time, however, death certificates are the gold standard for documenting the cause of death and were used as such in this study. In addition, although this study reported only on the first 23 states that provided complete data to the VA’s suicide mortality database, it appears that the first 23 states are representative of the United States as a whole in terms of geographic distribution and the range of state-specific suicide rates. As the database expands, analyses will continue to extend information and improve precision for female veterans who use VHA services. Finally, for this initial analysis, SMRs were chosen to estimate the true standardized rate ratios. The utility of this measure for dealing with sparse data while providing valid estimates to compare mortality between populations makes this approach preferable to other methods such as direct standardization (

30). Specifically, a relatively small number of suicides for a single year within certain age groups of VHA-utilizing female veterans made direct age-adjustment of suicide rates in this group infeasible at this time. However, given that SMRs only estimate the true rate ratio of interest, we conducted a sensitivity analysis computing gender-specific direct age-adjusted rate ratios for all veterans compared with nonveterans; the results demonstrated that the SMR truly does provide a conservative estimate, and time trends observed were very similar [see online

supplement]. Likewise, it is safe to assume that the SMR is an appropriate, conservative estimate to compare veterans who do and do not use VHA services.

In summary, these novel findings indicate a decline in the relative risk of suicide among VHA-utilizing veterans compared with their nonveteran peers despite continued increases among veterans who did not use VHA services. The VA Mental Health Enhancement Initiative launched in 2005 and the Suicide Prevention Program launched in 2007 are designed to provide readily available, integrated care through awareness and education campaigns, a 24-hour Veterans Crisis Line, and placement of suicide prevention coordinators to track and follow up with high-risk patients in each VA medical center, with evidence-based treatments available for high-risk patients. Research is needed to directly evaluate the impact of these programs overall on veteran suicide rates in recent years and to identify which components of the program are or are not effective. For example, a recent evaluation of Denmark’s suicide prevention clinics demonstrates a possible approach to evaluating national VA suicide prevention initiatives (

31). In addition, parallel research is needed to determine how to best engage eligible, at-risk veterans not currently utilizing VHA services.