Spending reductions resulting from an ongoing transition from use of branded to generic second-generation antipsychotics may have critical implications for Medicaid policy. In October 2008, risperidone became the first second-generation antipsychotic with high sales volume to become available generically (

1). Over the next four years, several additional second-generation antipsychotics came off patent, including olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone, and aripiprazole (

1). Patent protections for most other current second-generation antipsychotics, including asenapine, iloperidone, and lurasidone, are expected to expire by 2016 (

1). The resulting reduction in Medicaid expenditures for antipsychotic medications could substantially affect Medicaid medication budgets and the need for formulary restrictions on access to second-generation antipsychotic medications.

The market entry of second-generation antipsychotics beginning in the 1990s resulted in sharply higher Medicaid expenditures for antipsychotic medications (

2), as these branded medications largely replaced generic first-generation antipsychotics in schizophrenia treatment. Between 1999 and 2005, annual antipsychotic expenditures per Medicaid beneficiary more than doubled, while antipsychotic prescriptions per beneficiary increased 30% (

2). By 2009, antipsychotics accounted for nearly 15% of all Medicaid expenditures for medications (

3). Policy makers’ concerns about increased spending on second-generation antipsychotics led many states to impose formulary restrictions on second-generation antipsychotics (

2,

4–

7). However, this rationale for formulary restrictions for antipsychotics may be less relevant in an era when the availability of generic versions of most second-generation antipsychotic medications with high sales volume promises to substantially reduce Medicaid expenditures on second-generation antipsychotics.

Although the pharmaceutical industry and government agencies have published estimates of savings from the entry of generic versions of other types of medications (

8–

11), published estimates of the implications of generic second-generation antipsychotics on expenditures are not available to date. Using aggregate data on antipsychotic prescriptions and spending in Medicaid, this study developed estimates of the savings to the Medicaid program from use of generic risperidone during the years 2008 to 2011 and used these estimates to derive forecasts (projections) of Medicaid expenditures for all antipsychotic medications (

12).

Discussion

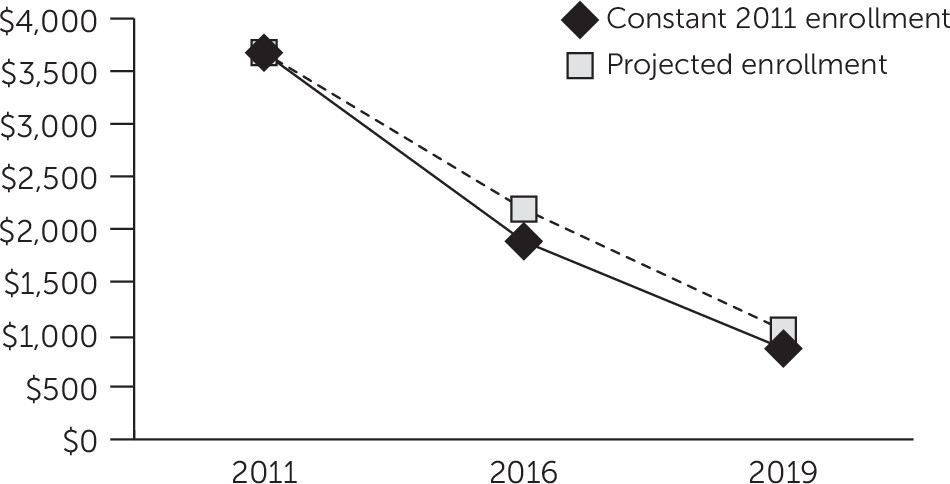

Within the next three or four years, the makeup of antipsychotic prescriptions in Medicaid will likely undergo a transition from predominantly branded medications to predominantly generic medications. In 2011, Medicaid spent more than $3.6 billion on second-generation antipsychotics. Five branded medications—aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine, ziprasidone, and paliperidone—accounted for the vast majority ($3.3 billion [90%]) of this spending. According to this study’s forecasts, patent expirations for these medications could result in a further reduction in Medicaid expenditures for antipsychotic medications of $1.8 billion (49%) by the year 2016 and of $2.8 billion (77%) by the year 2019.

Anticipated reductions in spending on antipsychotics should be factored into reassessments of the ongoing need for Medicaid formulary restrictions on second-generation antipsychotics. Medicaid has historically accounted for 70%−80% of all antipsychotic prescriptions in the United States (

19,

20), and rapid increases in antipsychotic expenditures following the introduction of branded second-generation antipsychotic medications in the 1990s led some states to impose formulary restrictions on access to these medications in Medicaid (

2,

4–

7). However, at best, these policies result in little or no net savings to Medicaid (

21) and, at worst, adversely affect patients’ medication access (

22–

24) and outcomes (

7,

21). Consequently, if Medicaid is entering a period of rapidly decreasing antipsychotic expenditures, states’ original rationale for formulary restrictions may be significantly eroded.

Actual reductions in Medicaid spending on antipsychotic medications could be lower than forecast, as a result of increased antipsychotic prescription volume in states where Medicaid program eligibility was expanded because of the ACA. A sensitivity analysis that incorporated actuarial estimates of future Medicaid enrollment levels indicated that although enrollment increases will result in a moderately greater volume of antipsychotic prescriptions, the rapid decrease in cost per prescription will drive Medicaid expenditures lower over time. Antipsychotic prescription volume will likely increase only moderately as enrollment increases, because individuals who qualify for Medicaid under a disability enrollment category, among whom antipsychotic use is concentrated (

3), will be underrepresented in the expansion population compared with existing Medicaid enrollees (

17).

The pace of the actual spending reduction will also depend on the extent of generic substitution in Medicaid and approval of new branded medications, among other factors. After generic risperidone entered the market, generic prescriptions rapidly achieved a nearly 100% share of all risperidone prescriptions for the same medication, but risperidone’s share of all prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotic remained virtually unchanged (

Table 1). This pattern suggests that as generic forms of branded second-generation antipsychotics become available, they will make up an increasing fraction of prescriptions for all second-generation antipsychotics, leading to a sharp decrease in total spending for second-generation antipsychotics. However, this long-term decline in spending for second-generation antipsychotics could be slowed or even reversed by aggressive marketing by the pharmaceutical industry of reformulations of second-generation antipsychotic medications or by new market approval of one or more novel antipsychotic medications. However, a recent survey of the psychotropic medication development pipeline suggests that this is unlikely (

25). No novel antipsychotic medications are expected to enter the market anytime soon, given that investments by major pharmaceutical manufacturers in the development of drugs for mental disorders has waned dramatically in recent years (

25).

Evidence of savings from the use of generic risperidone indicates that expiration of patents for second-generation antipsychotics will be associated with a large financial windfall for Medicaid. Medicaid savings from the use of generic risperidone increased annually between 2008 and 2011, from $25 million in 2008 to at least $599 million in 2011. Savings increased over the study period as a result of an 84% decrease in Medicaid costs per prescription for generic risperidone, a nearly 100% conversion from prescriptions for branded forms to generic forms of risperidone, and an overall increase in use of risperidone and other second-generation antipsychotic medications.

This is the first study to use a variable-price model to derive estimates of projected savings from the use of generic medications. Savings from risperidone use in 2011 could have been as high as $844 million if variable pricing is used to calculate the costs of branded risperidone. Variable pricing assumes that the projected price of branded risperidone increased at a rate proportional to the increase in prices for branded second-generation antipsychotics. Previous reports by the pharmaceutical industry and federal agencies of savings from use of generic medications have generally used constant-price models (

8–

11). However, the variable price model is more consistent with empirical evidence (

15,

16). The prices of branded medications have tended to increase over the course of their patent protection period, perhaps as a response to decreasing price sensitivity among payers (

15), whereas the prices of generic medications have tended to decrease over time (

16). Nevertheless, both models are used to project counterfactual expenditure levels that are not directly observable, so whether a variable-price model results in a more accurate estimate of actual savings compared with a constant-price model cannot be verified.

This study had limitations that may affect the interpretation of the results. First, only outpatient prescriptions were recorded in the database used for this study. The omission of inpatient prescriptions resulted in underestimation of overall Medicaid expenditures for antipsychotic medications. Second, this study relied on aggregate data reported by state Medicaid agencies. The completeness of these data is unverified, and some states had missing information that was imputed. A sensitivity analysis conducted without these imputed values found slightly lower overall spending levels and savings compared with the main analysis, but both analyses found very similar expenditure trends. Third, the average manufacturer rebate rate used to adjust Medicaid expenditure amounts was drawn from a government report (

14). Actual rebate amounts for specific medications and states are not publicly available and may have deviated substantially from this average. Finally, some of the results may be sensitive to the study’s time frame. The study time frame overlapped with an economic recession, during which the rate of new Medicaid enrollment increased temporarily (

17), and preceded an expected surge in Medicaid enrollment (

17). A sensitivity analysis suggested that these enrollment changes were unlikely to have more than a moderate impact on the study’s results, because the transition to use of much lower cost generic medications is the predominant influence on current spending trends.